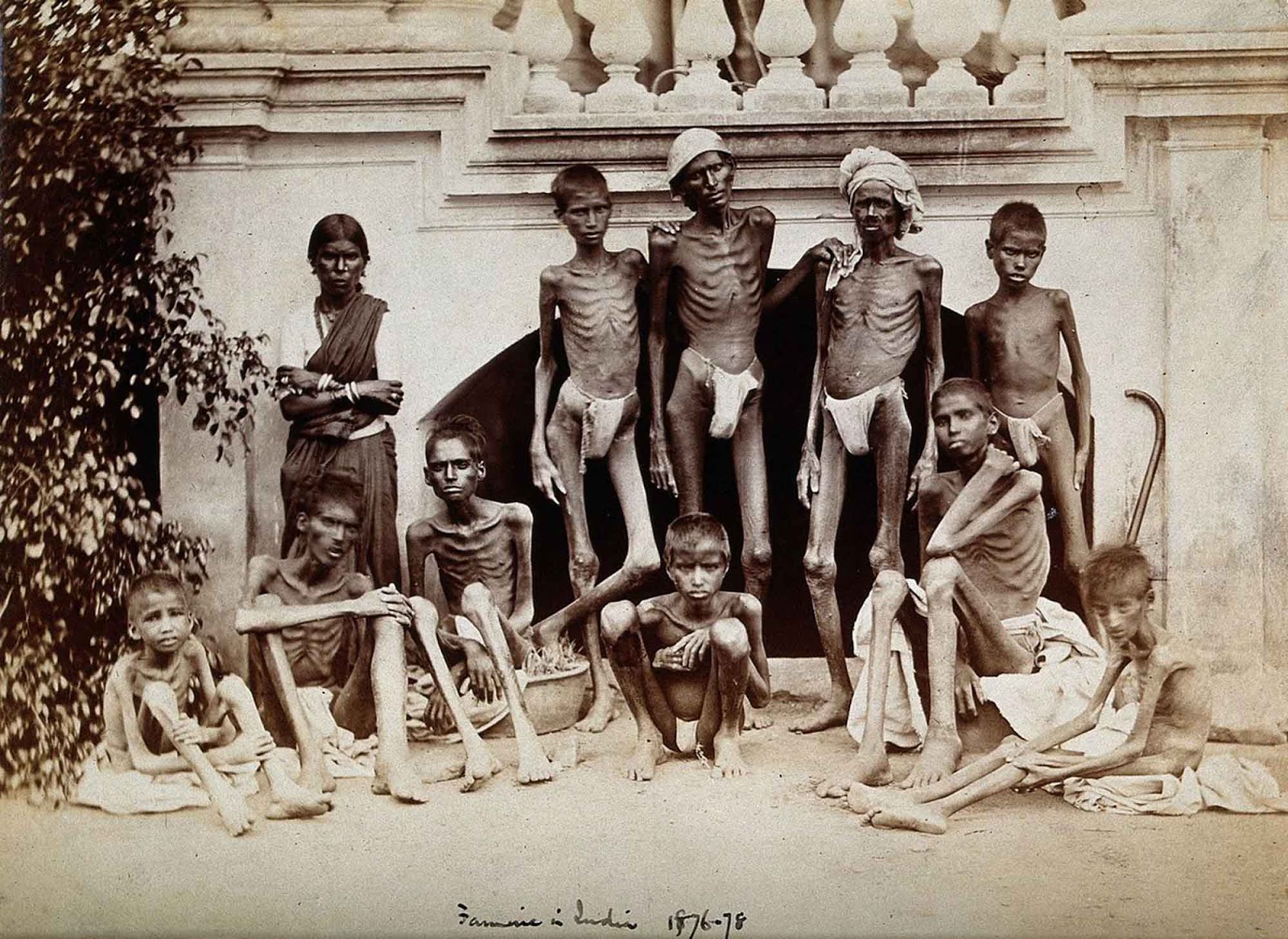

The famine ultimately covered an area of 670,000 square kilometers (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totaling 59 million. In part, the Great Famine may have been caused by an intense drought resulting in crop failure in the Deccan Plateau. But, the regular export of grain by the colonial government; during the famine, the viceroy, Lord Lytton, oversaw the export to England of a record 6.4 million hundredweight (320,000 ton) of wheat, this weaken the rich cultural and economic strength especially of southern India. Perhaps most disturbingly, Lord Lytton, the Viceroy, held a grand banquet for 60,000 people, in honor of Queen Victoria’s coronation. The cultivation of alternate cash crops, in addition to the commodification of grain, played a significant role in the events. The famine occurred at a time when the colonial government was attempting to reduce expenses on welfare. Earlier, in the Bihar famine of 1873–74, severe mortality had been avoided by importing rice from Burma. However, the Government of Bengal and its Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Richard Temple, were criticized for excessive expenditure on charitable relief. Sensitive to any renewed accusations of excess in 1876, Temple, who was now Famine Commissioner for the Government of India, insisted not only on a policy of laissez-faire with respect to the trade-in grain but also on stricter standards of qualification for relief and on more meager relief rations. The excessive mortality and the renewed questions of “relief and protection” that were asked in its wake, led directly to the constitution of the Famine Commission of 1880 and to the eventual adoption of the Provisional Famine Code in British India. After the famine, a large number of agricultural laborers and handloom weavers in South India emigrated to British tropical colonies to work as indentured laborers in plantations. The excessive mortality in the famine also neutralized the natural population growth in the Bombay and Madras presidencies during the decade between the first and second censuses of British India in 1871 and 1881 respectively. The Great Famine was to have a lasting political impact on events in India. Among the British administrators in India who were unsettled by the official reactions to the famine and, in particular by the stifling of the official debate about the best form of famine relief, were William Wedderburn and A. O. Hume. Less than a decade later, they would found the Indian National Congress and, in turn, influence a generation of Indian nationalists. Among the latter were Dadabhai Naoroji and Romesh Chunder Dutt for whom the Great Famine would become a cornerstone of the economic critique of the British Raj. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe