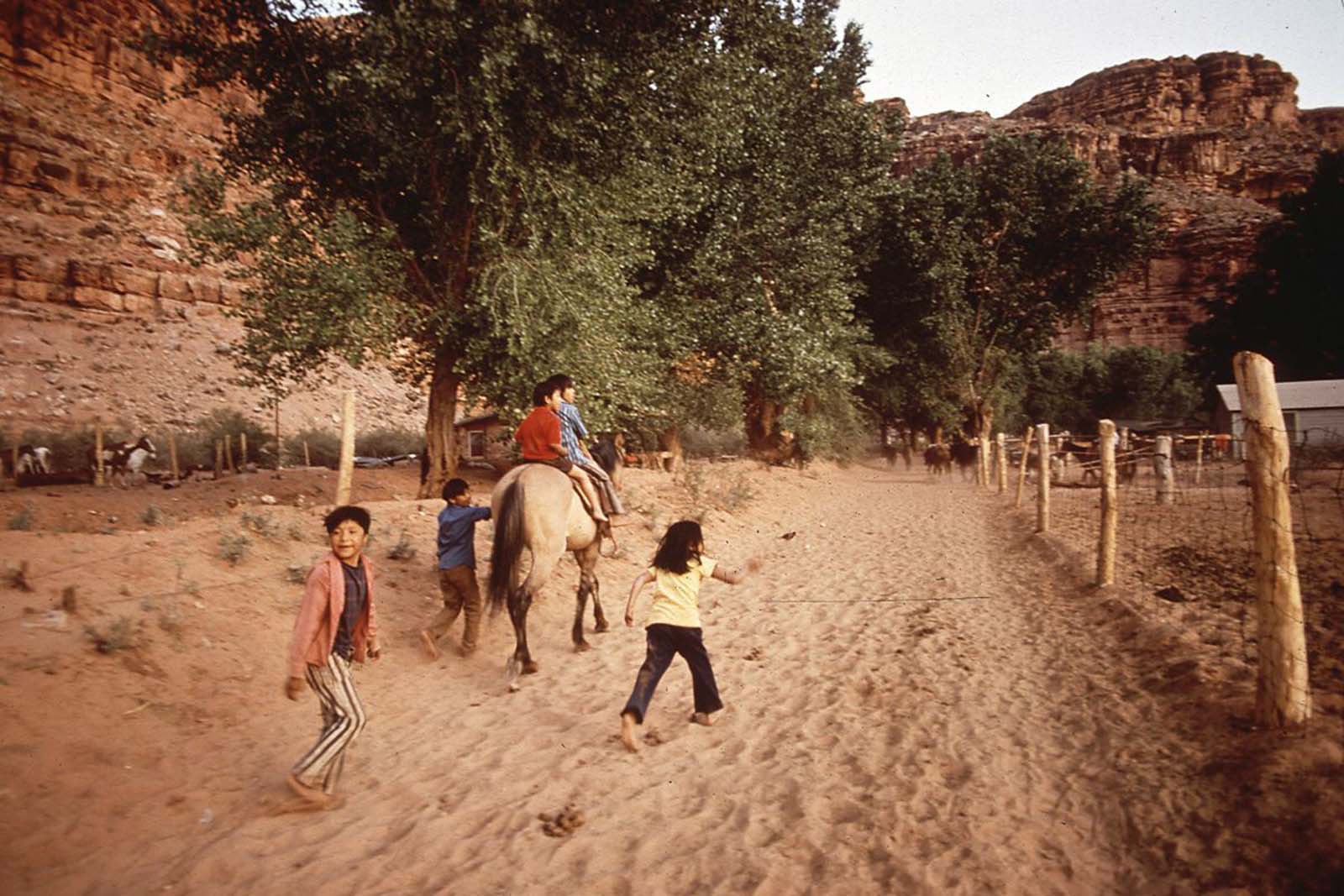

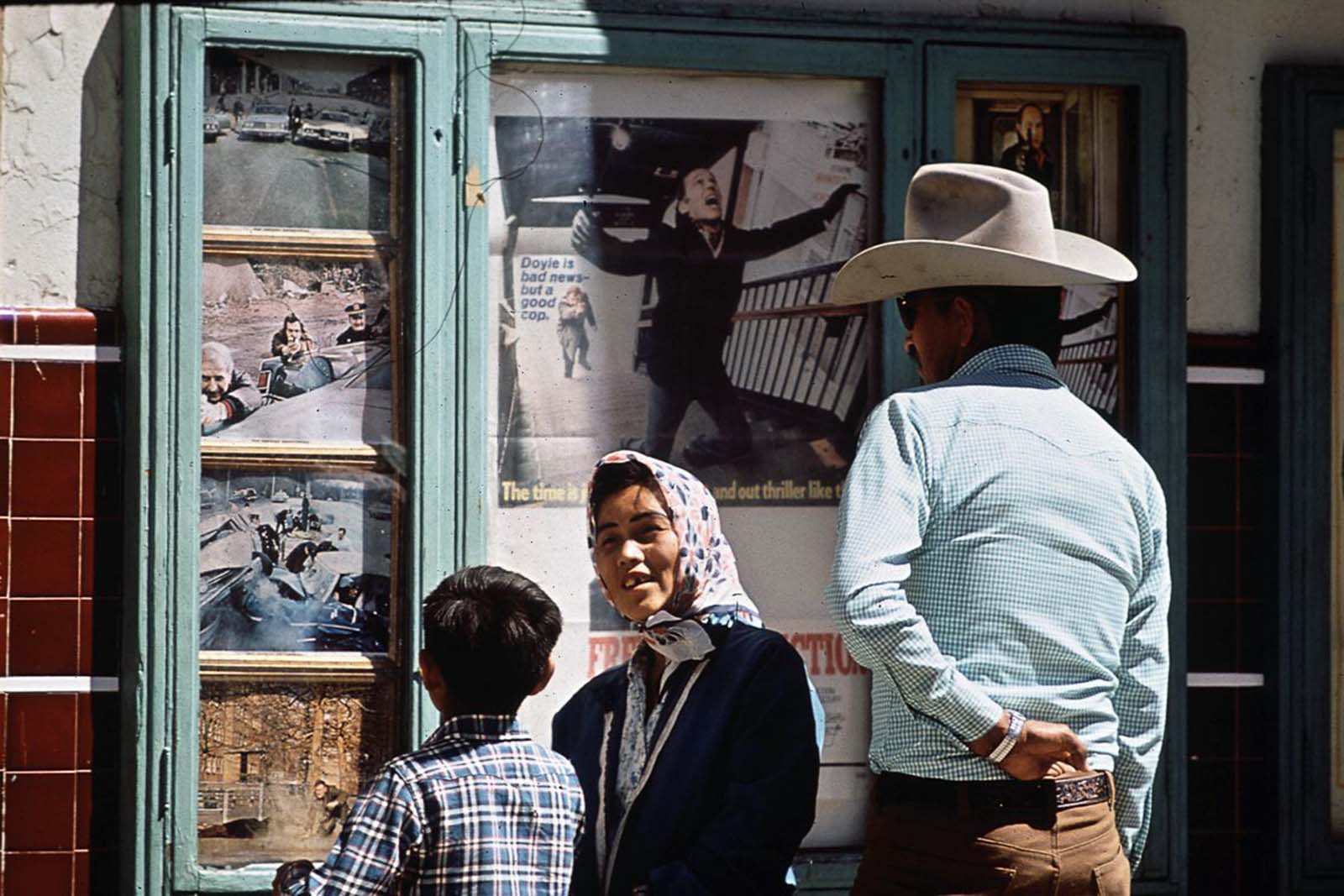

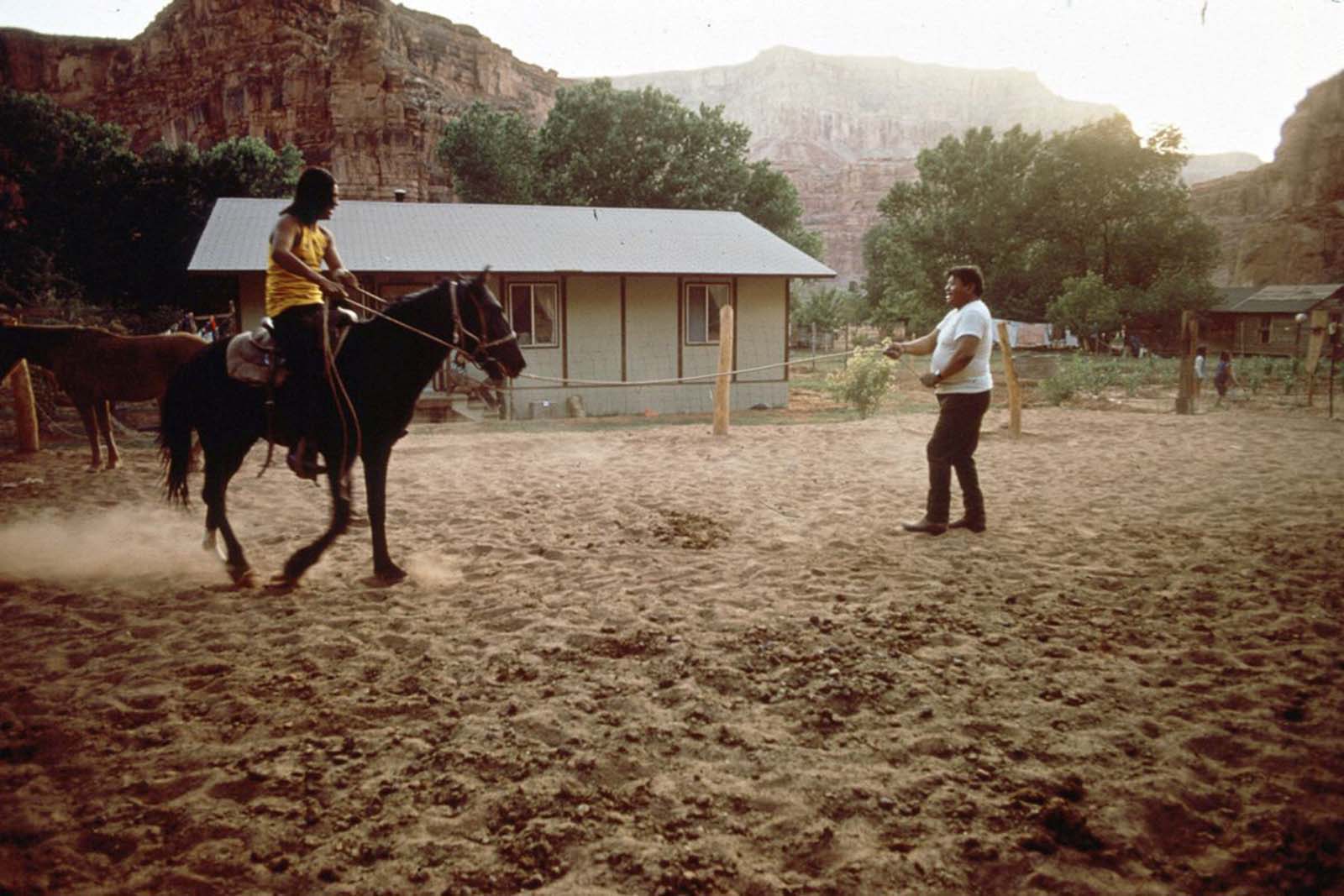

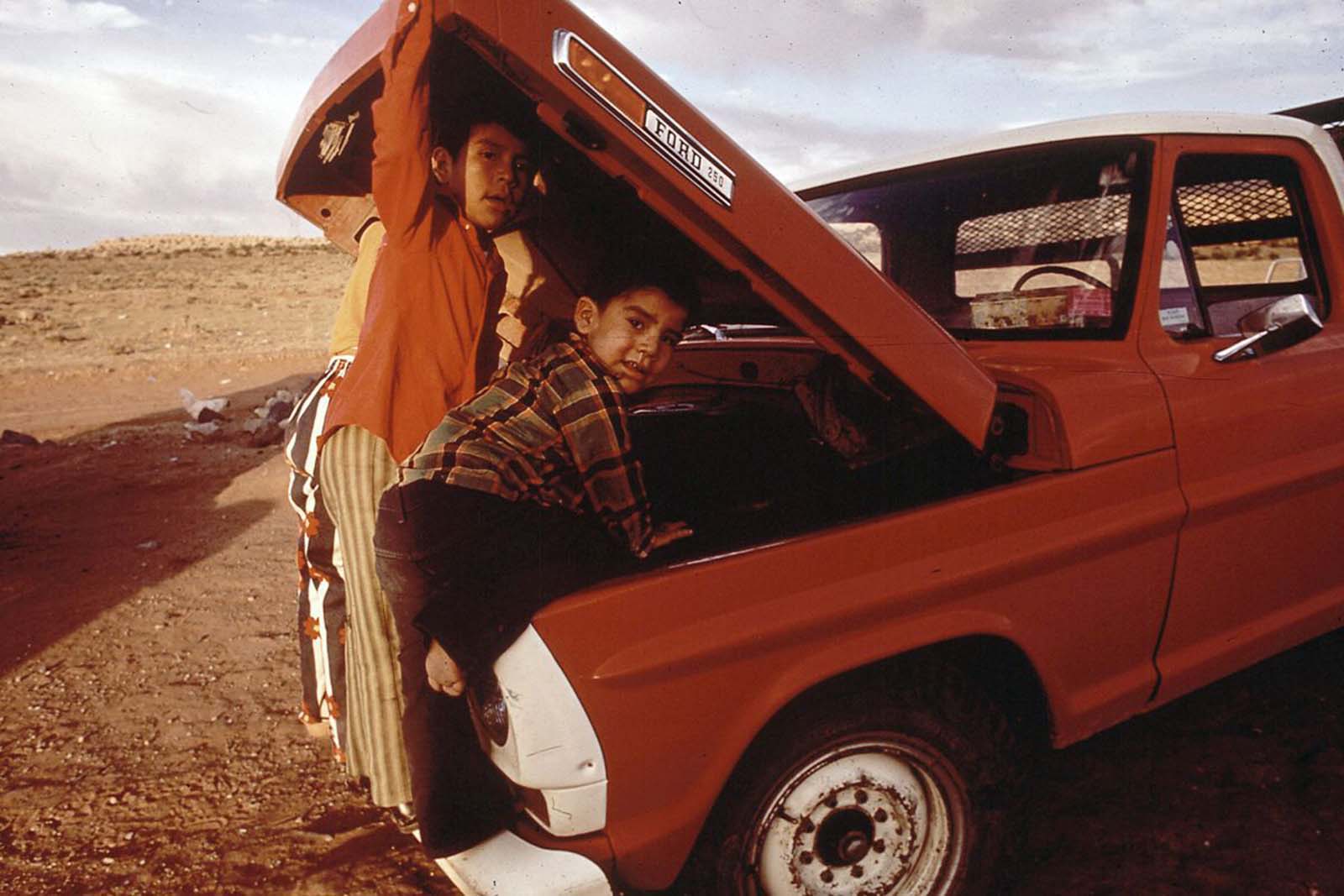

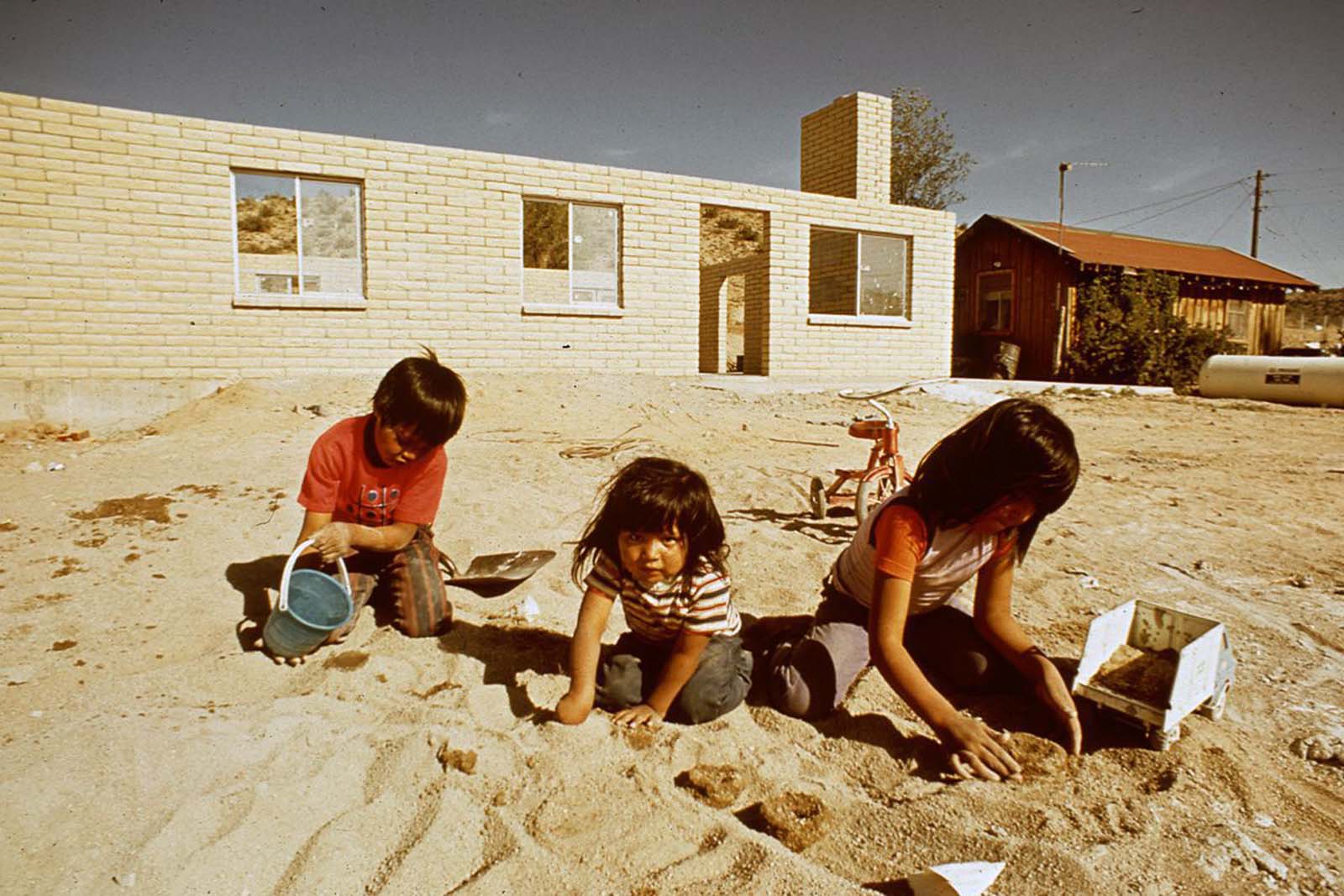

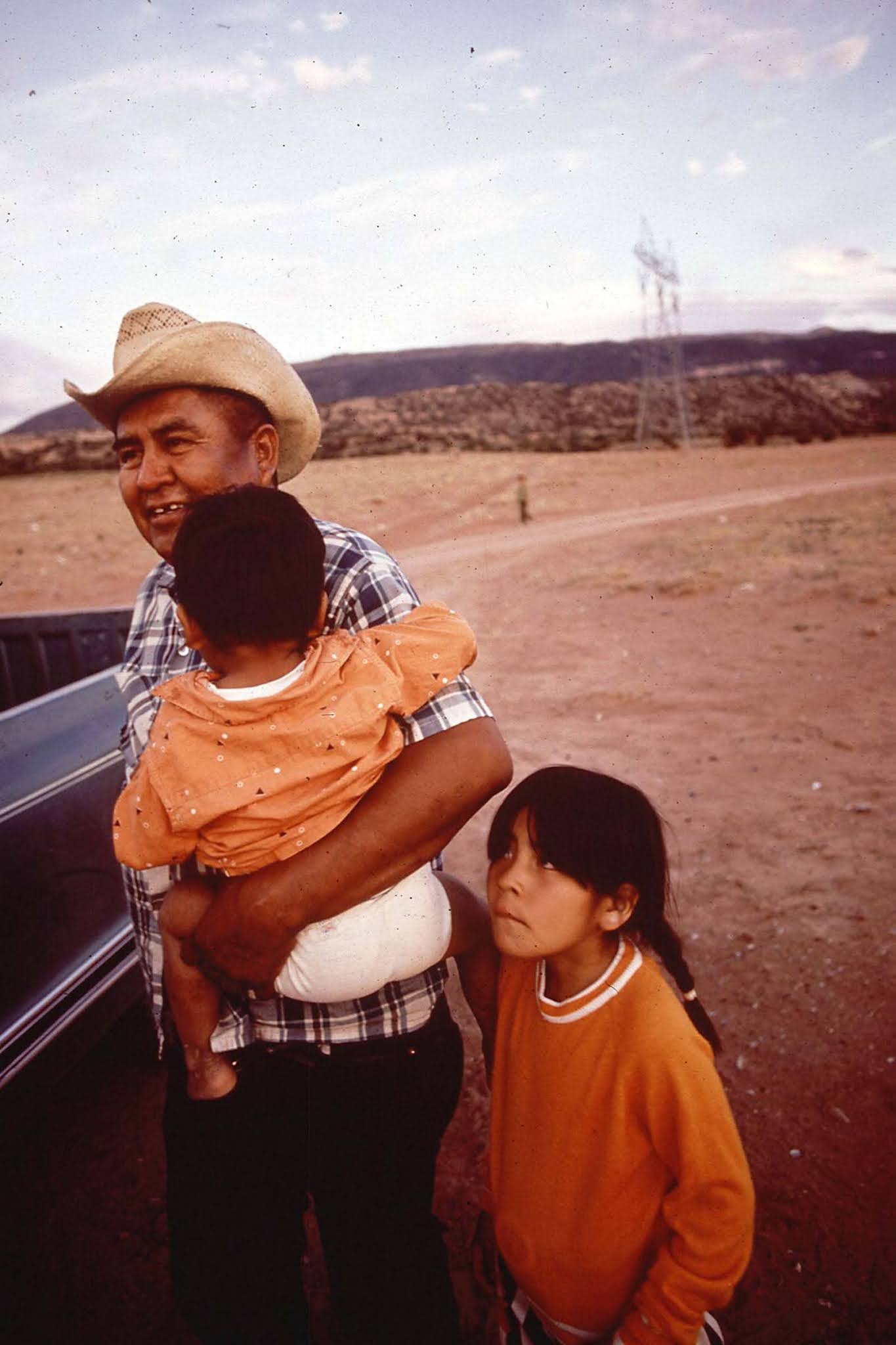

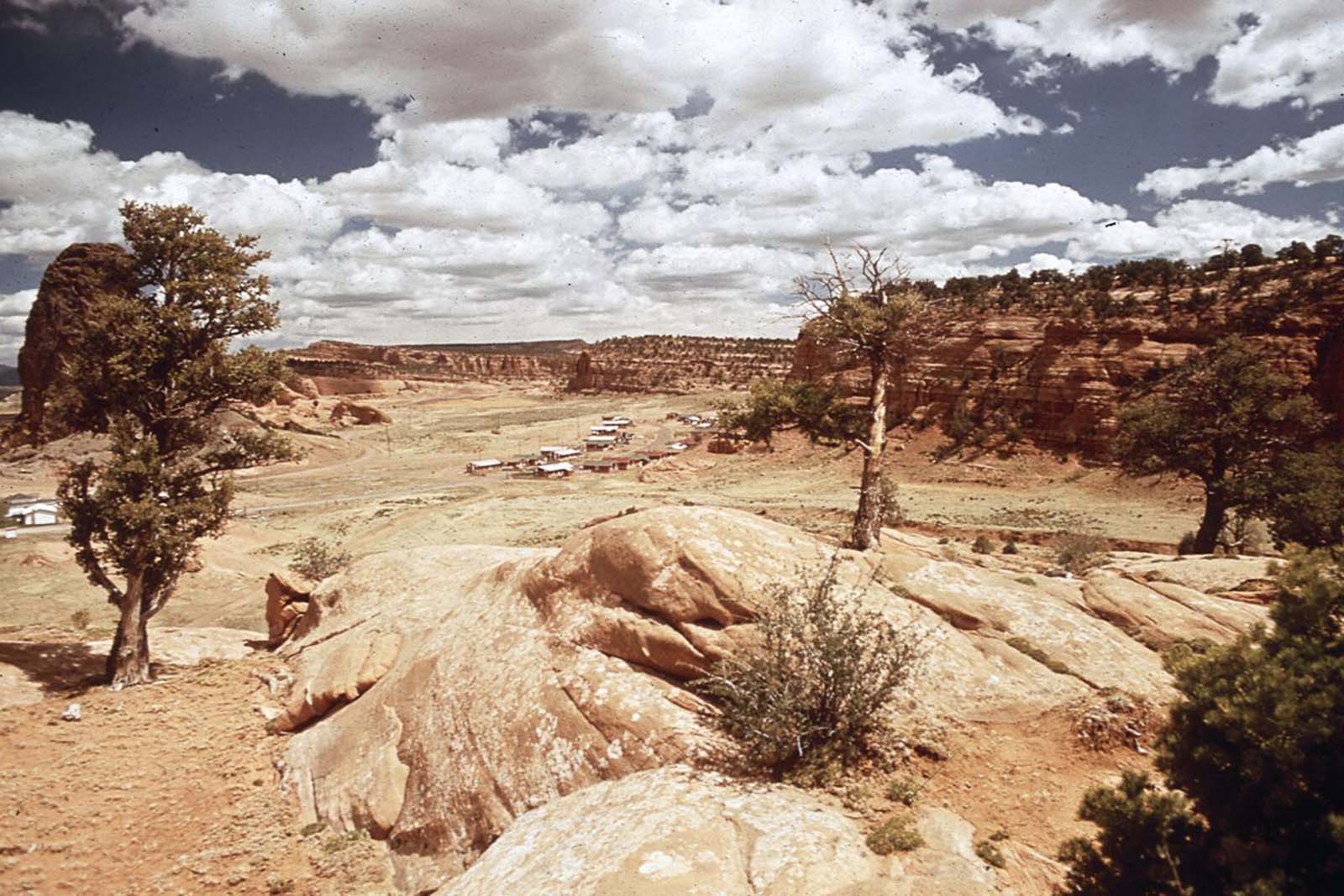

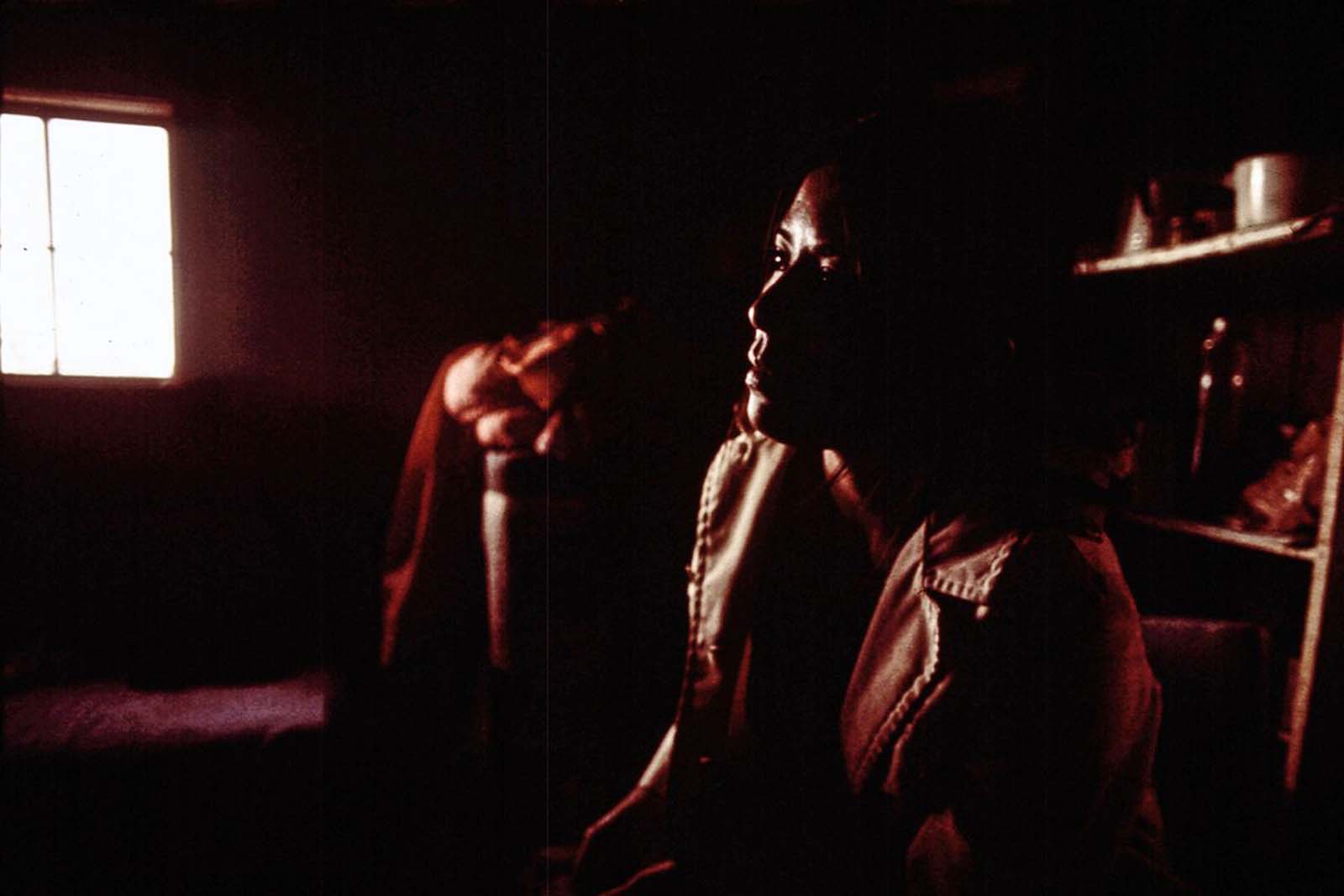

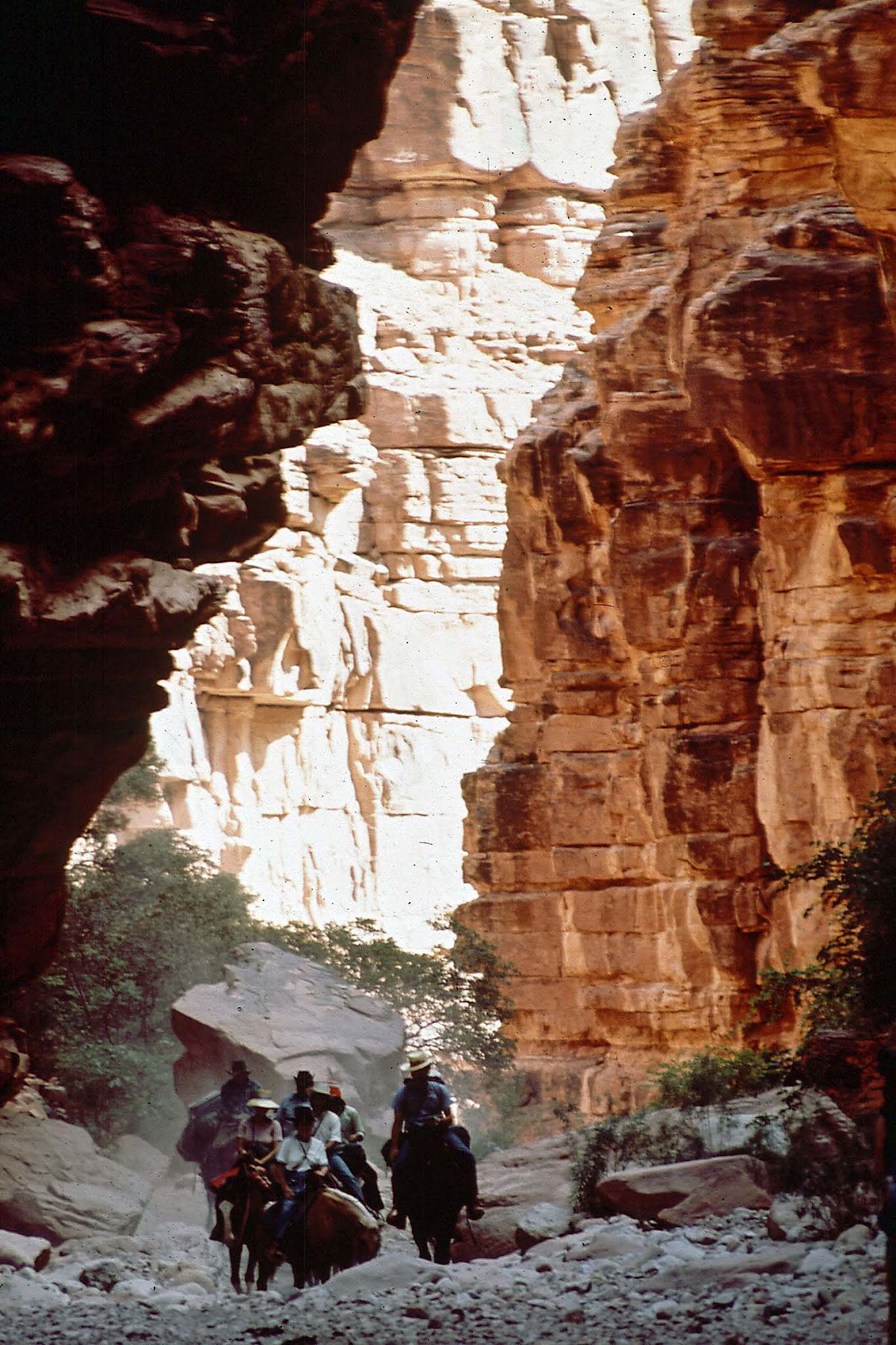

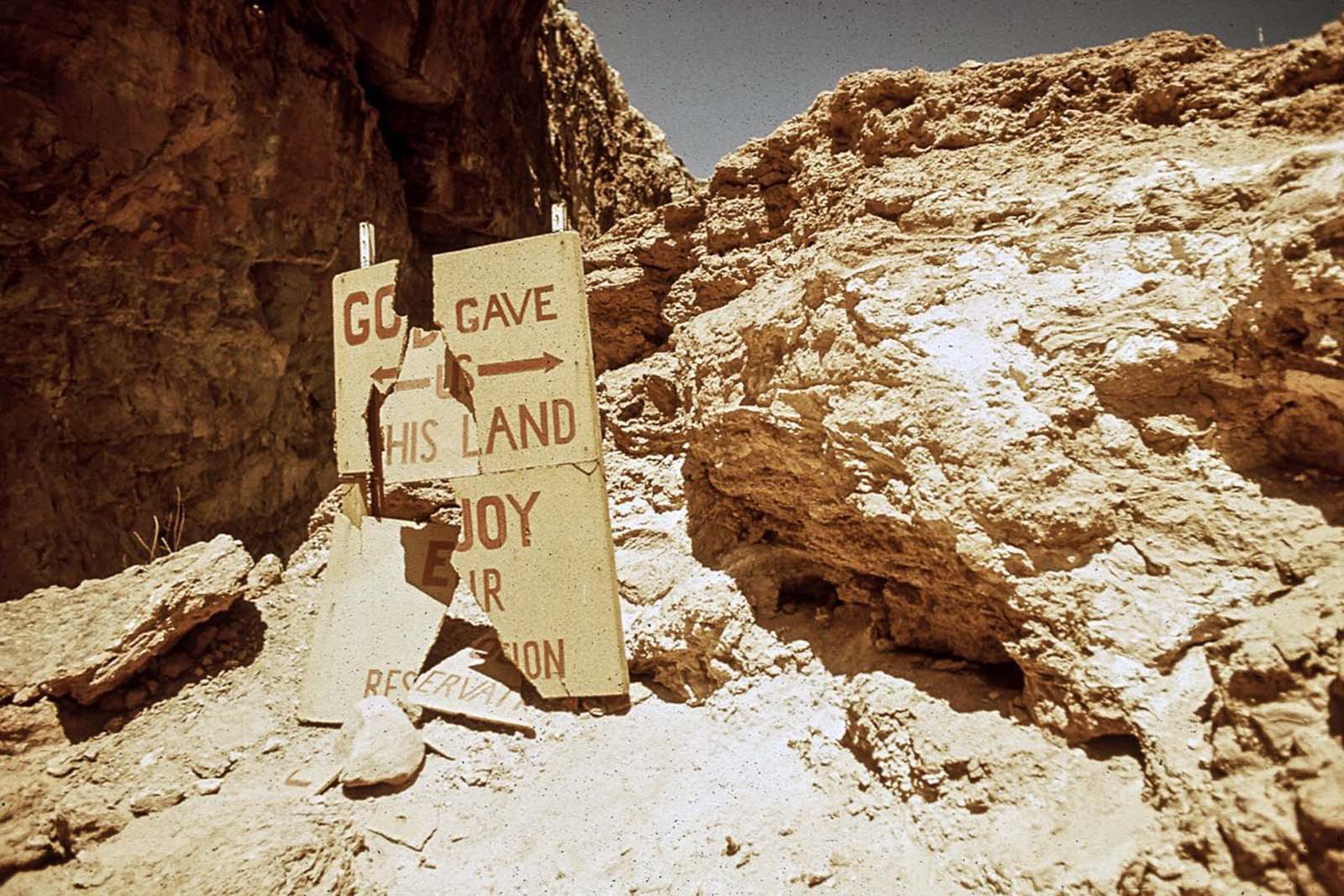

Eiler’s pictures show a world that was becoming modernized and similar to mainstream America but at the same time, was still clinging tenaciously to their traditions, forged over millennia. In a way, the images reveal people who valued kinship and who had one noble, and seemingly simple goal: the protection of a deeply-rooted culture. His subjects are natural and act as themselves, a stark contrast to the wooden and forced appearances of Native Americans made to pose in the sepia photographs. Looking at these photographs, we see that the standards of living in the 1970s were low, and that many Navajo families were struggling to make ends meet. Although the mining of coal and uranium was a substantial source of income for the tribe during the second half of the twentieth century, Navajo miners often worked in dangerous conditions and for very low wages. At the time of Eiler’s visit, the unemployment rate in the Navajo Nation was around 32 percent. And an “above average” household was more or less one that had four walls and a roof, running water and electricity were considered rare luxuries. Back in 1972, as the Native American rights movement was in its earliest days, Eiler visited three reservations belonging to the Navajo, Hopi and Havasupai reservations. The Navajo nation‘s reservation was the largest, about the same size as the US state of West Virginia. The photographer also visited the village of Supai, nestled in the Grand Canyon of Colorado, said to be the most remote human habitation in the country and accessible only by an eight-mile hike through rocky terrain or via helicopter. The photos cover a wide range of subjects, from a sheep paddock in the desert sands of the Navajo reservation in Arizona, a retinue of cute lambs staring back at the camera, their white wool contrasting strongly with the ochre ground underneath their hooves, to a Navajo woman in a bright red blouse standing for a quick snap near the Arizonan town of Shiprock. Others show Native American families and men out and about, gardening, horse riding and being at home. While clearly getting on with life, it is obvious that the living conditions were at times very different from most American communities. The Native American reservations are an area of land tenure governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation under the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, rather than by the government of the state in which it is located. The 326 Indian reservations in the United States are associated with specific Native American nations, often on a one-to-one basis. Some of the country’s 574 federally recognized tribes govern more than one reservation, while some share reservations, and others have no reservation at all. In addition, because of past land allotments, leading to sales to non–Native Americans, some reservations are severely fragmented, with each piece of tribal, individual, and privately held land being a separate enclave. This jumble of private and public real estate creates significant administrative, political and legal difficulties. The collective geographical area of all reservations is 87,800 sq mi (227,000 km2), approximately the size of the state of Idaho. While most reservations are small compared to U.S. states, there are twelve Indian reservations larger than the state of Rhode Island. (Photo credit: Terry Eiler / National Archives / HEM News Agency) Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe