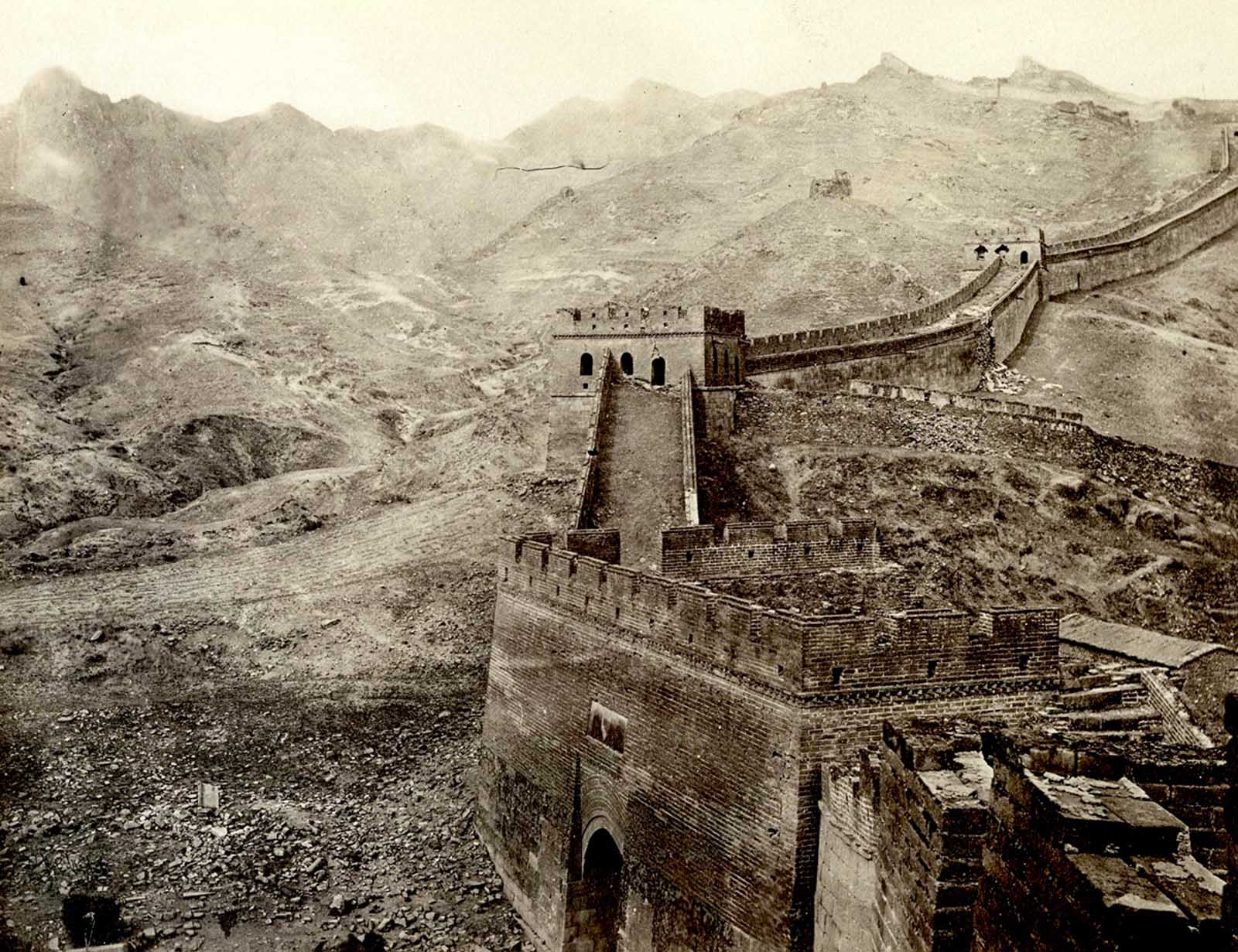

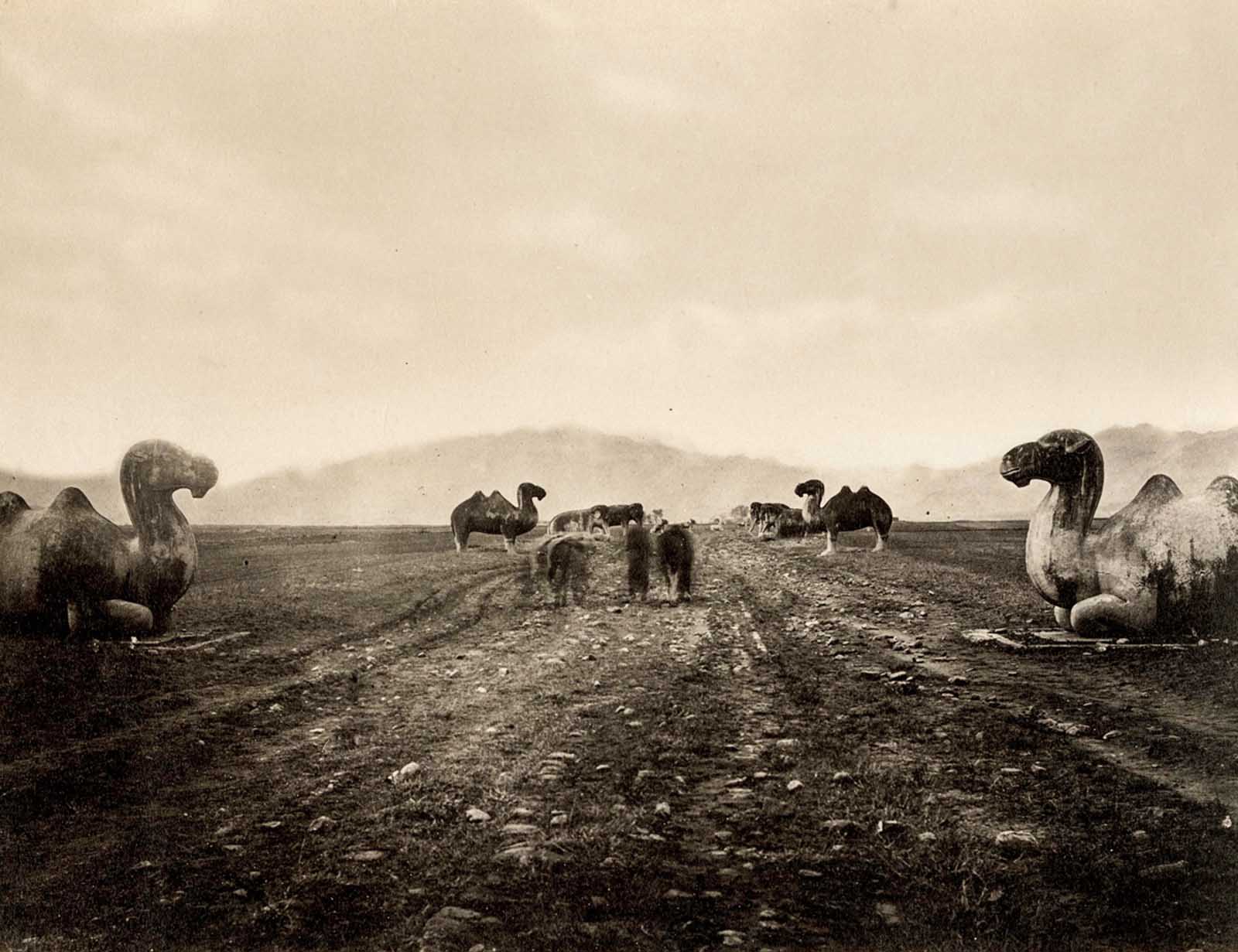

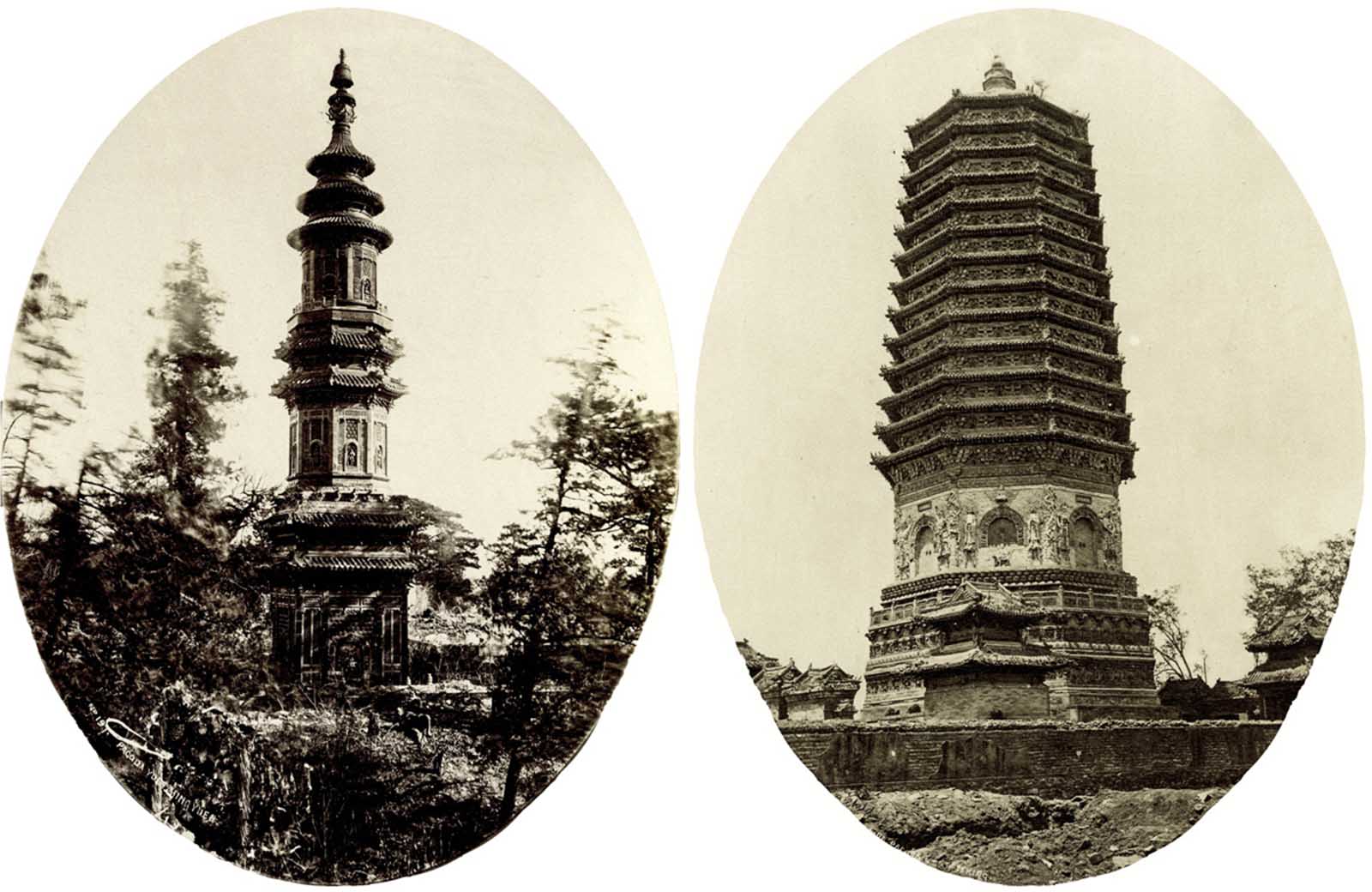

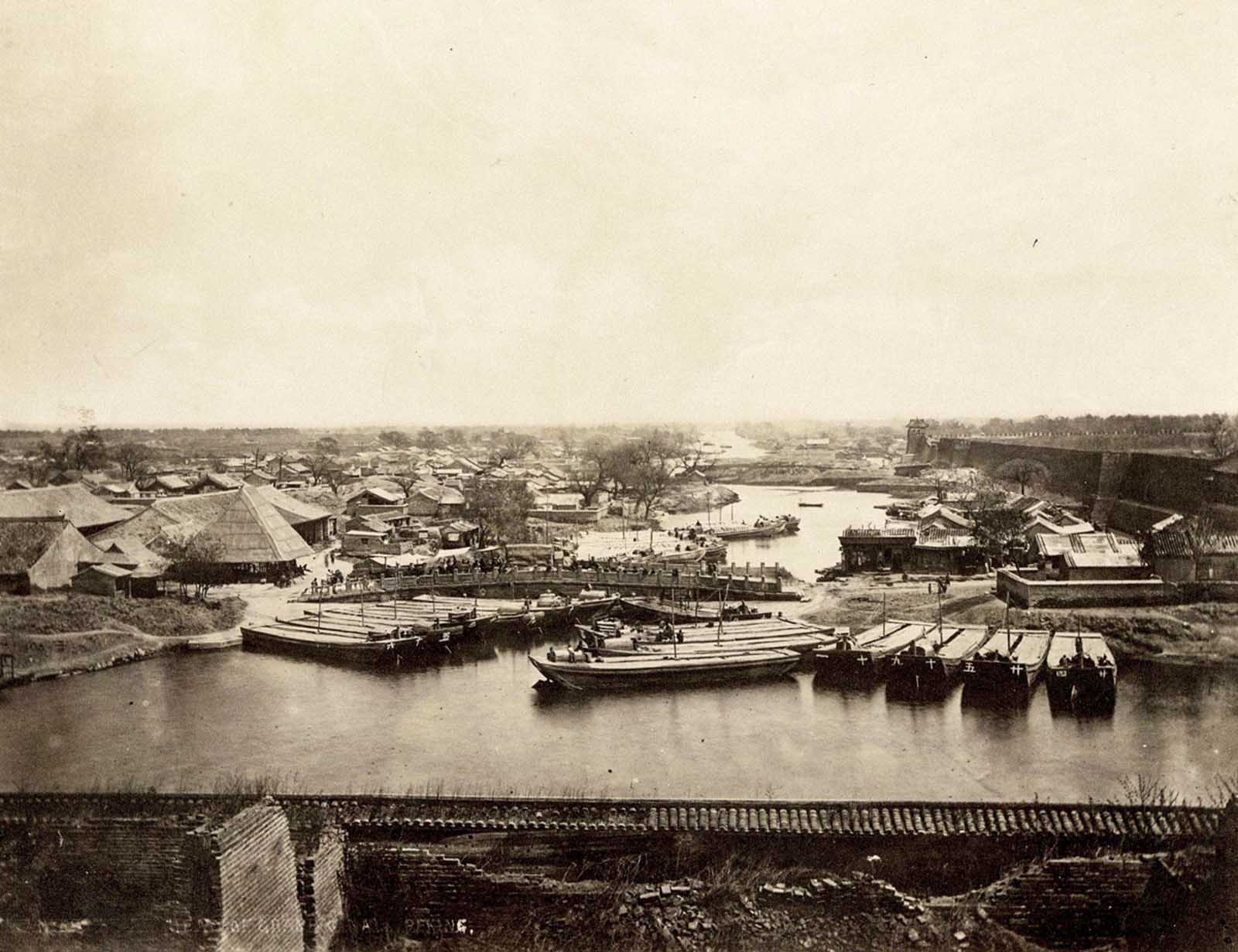

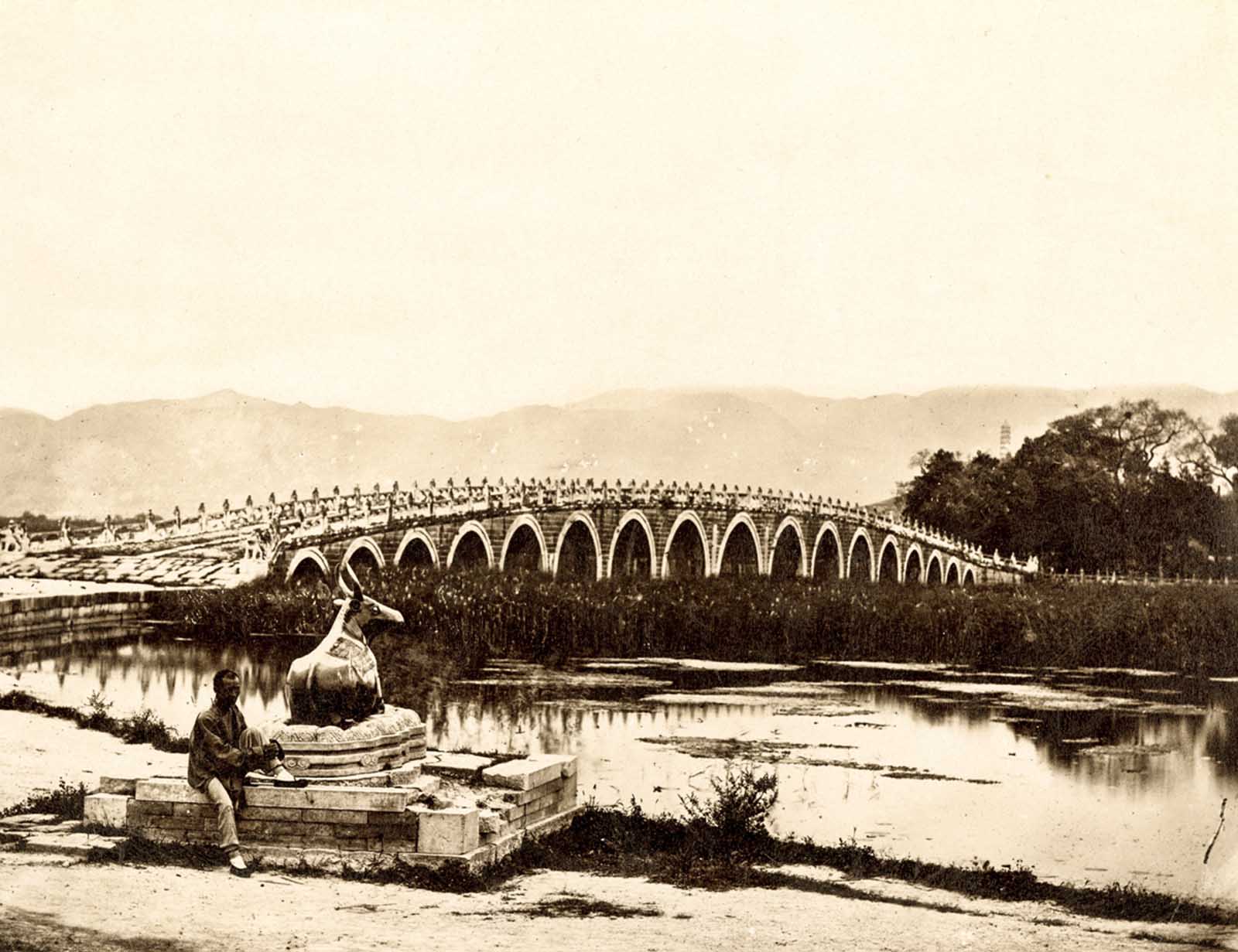

The 29-year-old Englishman left behind his wife and three children to become one of roughly 100 foreigners living in the late Qing dynasty’s capital, taking his camera along with him. Unlike his contemporary photographers, Child chose to remain in China rather than return home and publish his photographs for instant renown. This meant that his own works went somewhat under the radar; it also means, however, that as a fluent Mandarin speaker and known resident in Peking, Child was able to get access to events and people his contemporaries were not. Over the course of the next 20 years, he took some 200 photographs, capturing the earliest comprehensive catalog of the customs, architecture, and people during China’s last dynasty. Child photographed the Great Wall as well as pagodas, temples, bridges, crowded harbors, roadsides lined with stone sculptures, and humble storefronts. He documented the practice of dismantling palace walls damaged by decay or war and recycling the stones for other construction. In his captions, letters, and journals he complained about dirty streets, insects, and rat infestations. He gently mocked local superstitions, the sound of temple bells that rang in “harmonious discord” and funeral rituals that “excel in pomp and expenditure”. In 1889, Thomas Child returned to England. He remained infatuated with China, and he gave his family home at the outskirts of London a Chinese name that has been roughly translated as Studio of Everlasting Tranquillity. He was killed in 1898 when his horse-drawn carriage overturned. His family kept some of his paperwork, but few other records survive. (Photo credit: Thomas Child / Stephan Loewentheil Historical Photography of China Collection / Courtesy of the Sidney Mishkin Gallery). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe