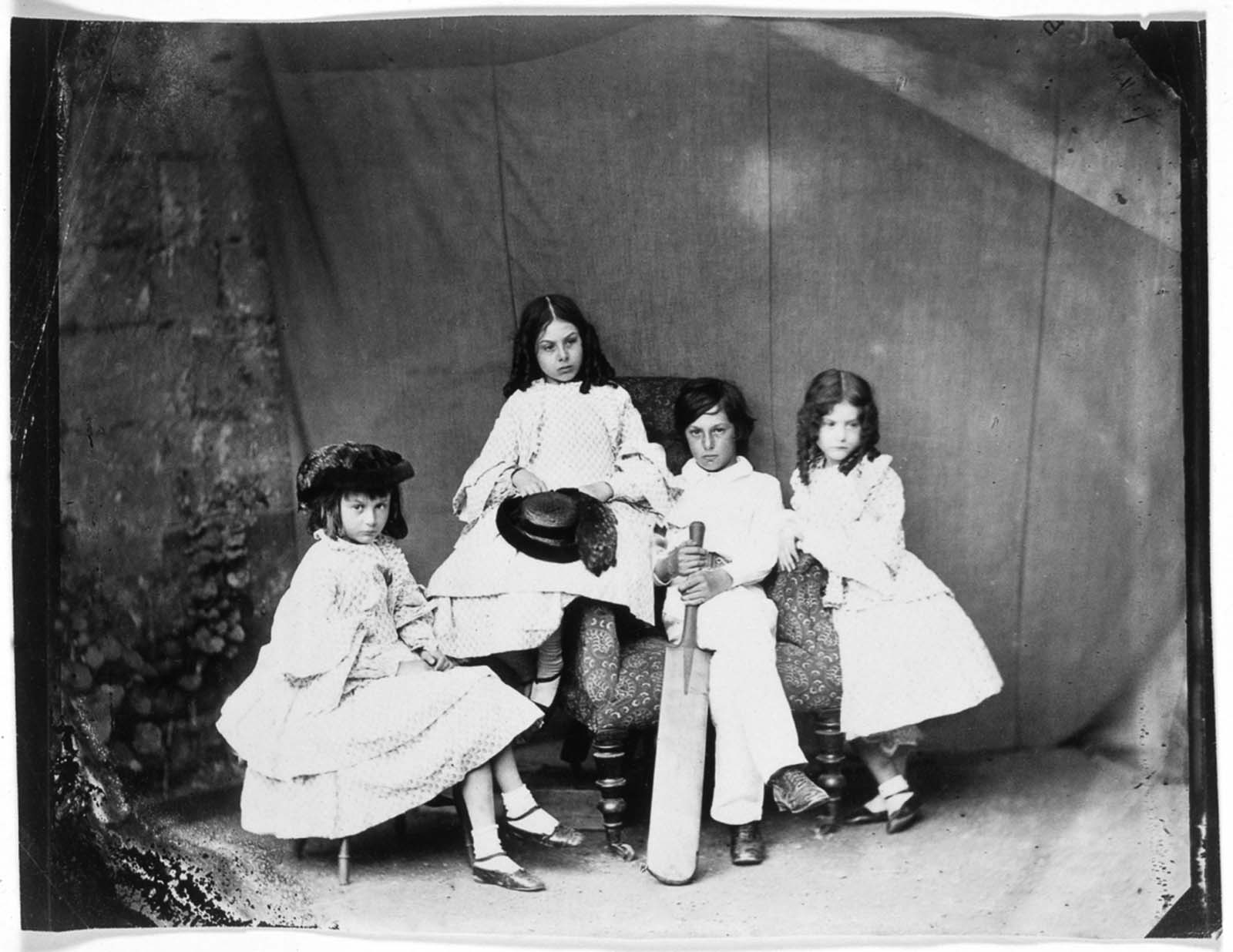

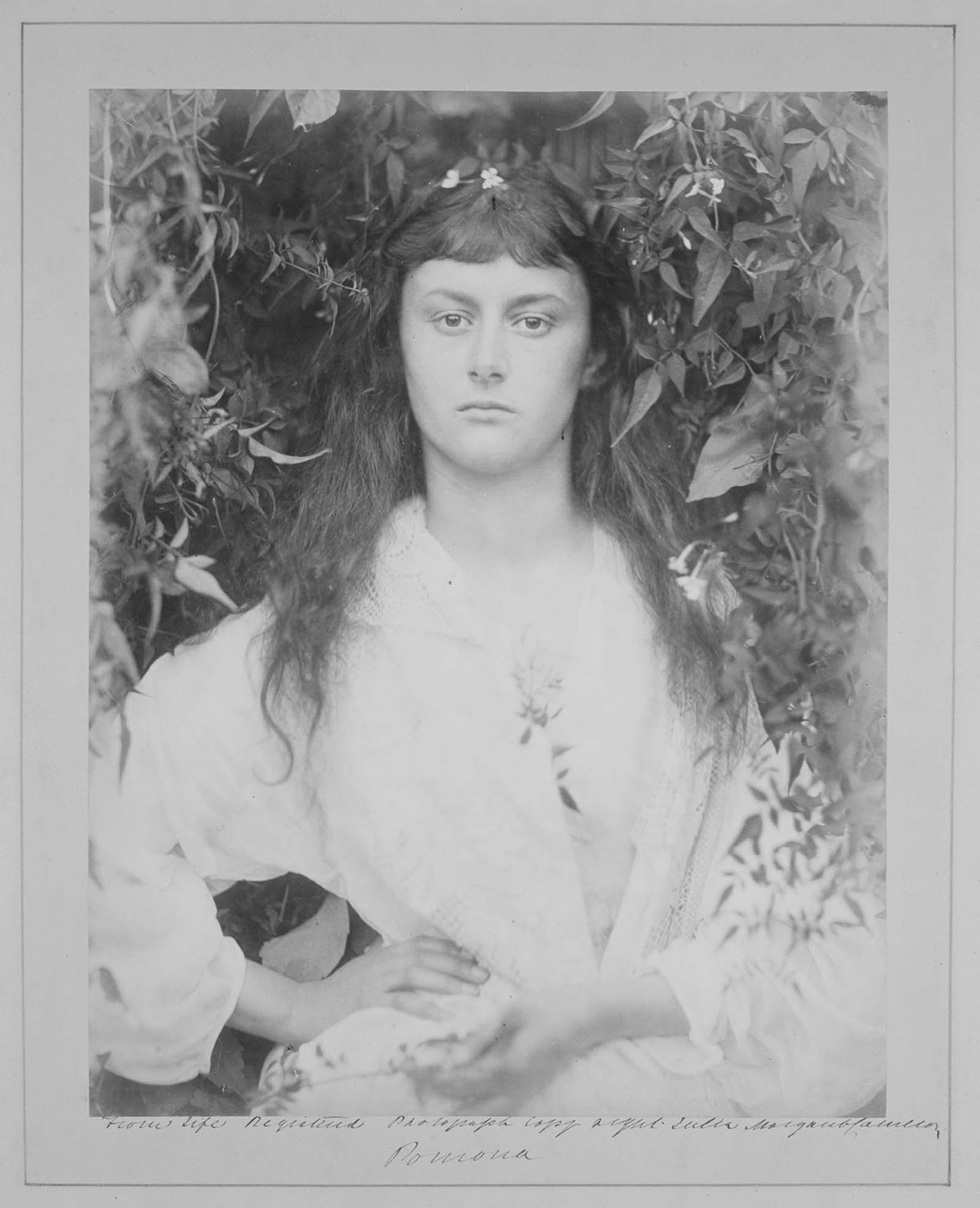

Over the next few years, Carroll would become a close friend of the Liddell family. Alice and her sisters were frequent models for Carroll’s photography, and he often took the children on outings. On July 4th, 1862, Carroll and the Rev. Robinson Duckworth took the girls boating up the Isis. Alice later recalled that as the company took tea on a shaded bank, she implored Carroll to “tell us a story.” According to Carroll, “in a desperate attempt” and “without the least idea what was to happen afterwards,” he sent his heroine “straight down a rabbit-hole.” Upon Alice’s urging, Carroll began writing down his tale. On November 26, 1864, he presented her with an elaborate hand-illustrated manuscript, titled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. When Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published a year later, Alice Liddell became immortalized as the inspiration for Carroll’s much-loved literary character. But unlike the fictional “Alice,” Alice Liddell grew up. By the time Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There was published, she was almost 20 years old, and Carroll’s close friendship with the Liddell family had weakened. His sequel can be seen as a fond farewell to Alice as she enters adulthood. In 1880, Alice married amateur cricket player Reginald Hargreaves. She lived the cultured life of a country lady in Lyndhurst, England. She had three sons, two of whom were killed in World War I. To help pay taxes after the death of her husband, Alice put the original Under Ground manuscript up for auction in 1928. Alice traveled to the United States in 1932 to receive an honorary doctorate from Columbia University in celebration of the centennial anniversary of Carroll’s birth. She died two years later.

Lewis Carrol and Alice

Many of Carroll’s photographs of Alice and other children can seem downright prurient to our eyes. As Carroll’s biographer Jenny Woolf writes in a 2010 essay for the Smithsonian, “of the approximately 3,000 photographs Dodgson made in his life, just over half are of children—30 of whom are depicted nude or semi-nude.” Some of his portraits—even those in which the model is clothed—might shock 2010 sensibilities, but by Victorian standards they were… well, rather conventional. Photographs of nude children sometimes appeared on postcards or birthday cards, and nude portraits—skillfully done—were praised as art studies […]. Victorians saw childhood as a state of grace; even nude photographs of children were considered pictures of innocence itself. Woolf admits that Carroll’s interest, as scholars have speculated for decades, may have been less than innocent, prompting Vladimir Nabokov to propose “a pathetic affinity” between Carroll and the narrator of Lolita. The evidence for Carroll’s possible involvement is highly suggestive but hardly conclusive. Burgett summarizes the claims as only speculative at best: “The entire controversy is an almost century-long debate, and one that doesn’t seem to be making any major progress in either direction.” In a Slate review of Woolf’s Lewis Carroll biography, Seth Lerer also acknowledges the controversy, but reads the photographs of Alice, her sisters, and friends as representative of larger trends, as “brilliant testimonies to the taste, the sentiment, and perhaps the sexuality of mid-Victorian England.”

Comparison with fictional Alice

The extent to which Dodgson’s Alice may be or could be identified with Liddell is controversial. The two Alices are clearly not identical, and though it was long assumed that the fictional Alice was based very heavily on Liddell, recent research has contradicted this assumption. Dodgson himself claimed in later years that his Alice was entirely imaginary and not based upon any real child at all. There was a rumor that Dodgson sent Tenniel a photo of one of his other child-friends, Mary Hilton Badcock, suggesting that he used her as a model, but attempts to find documentary support for this theory have proved fruitless. Dodgson’s own drawings of the character in the original manuscript of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground show little resemblance to Liddell. Biographer Anne Clark suggests that Dodgson might have used Edith Liddell as a model for his drawings. There are at least three direct links to Liddell in the two books. First, he set them on 4 May (Liddell’s birthday) and 4 November (her “half-birthday”), and in Through the Looking-Glass the fictional Alice declares that her age is “seven and a half exactly”, the same as Liddell on that date. Second, he dedicated them “to Alice Pleasance Liddell”. Third, there is an acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking-Glass. Reading downward, taking the first letter of each line, spells out Liddell’s full name. The poem has no title in Through the Looking-Glass, but is usually referred to by its first line, “A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky”. (Photo credit: Royal Photographic Society / Getty Images. Text: University of Maryland, University Libraries). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe