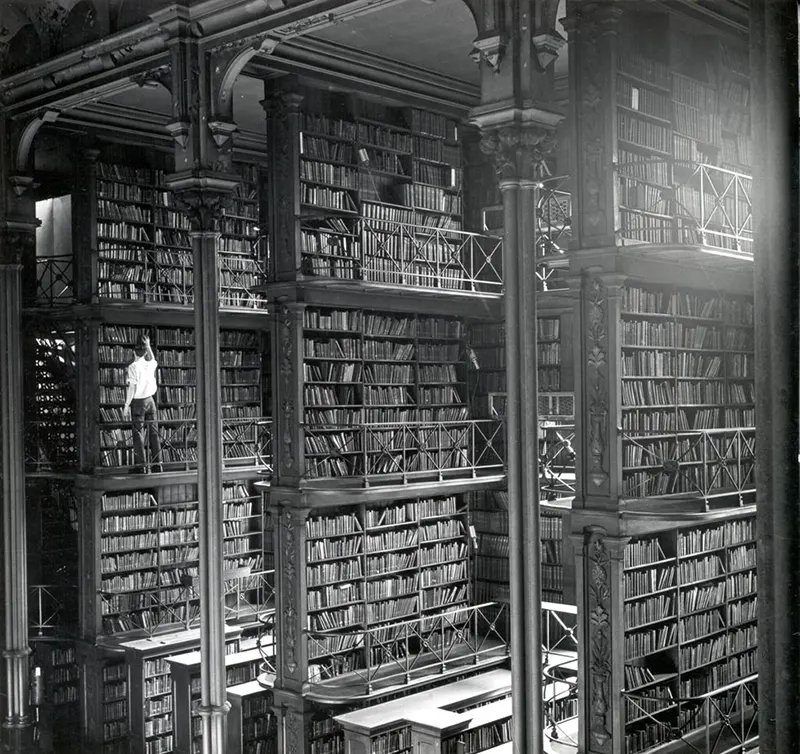

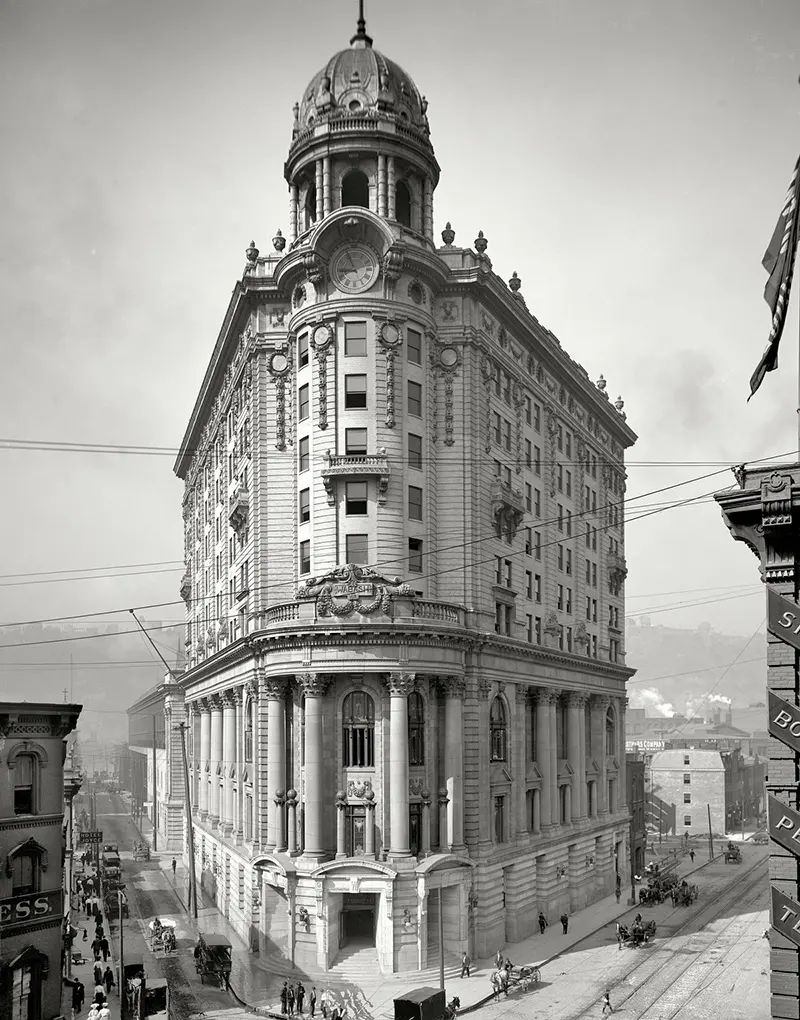

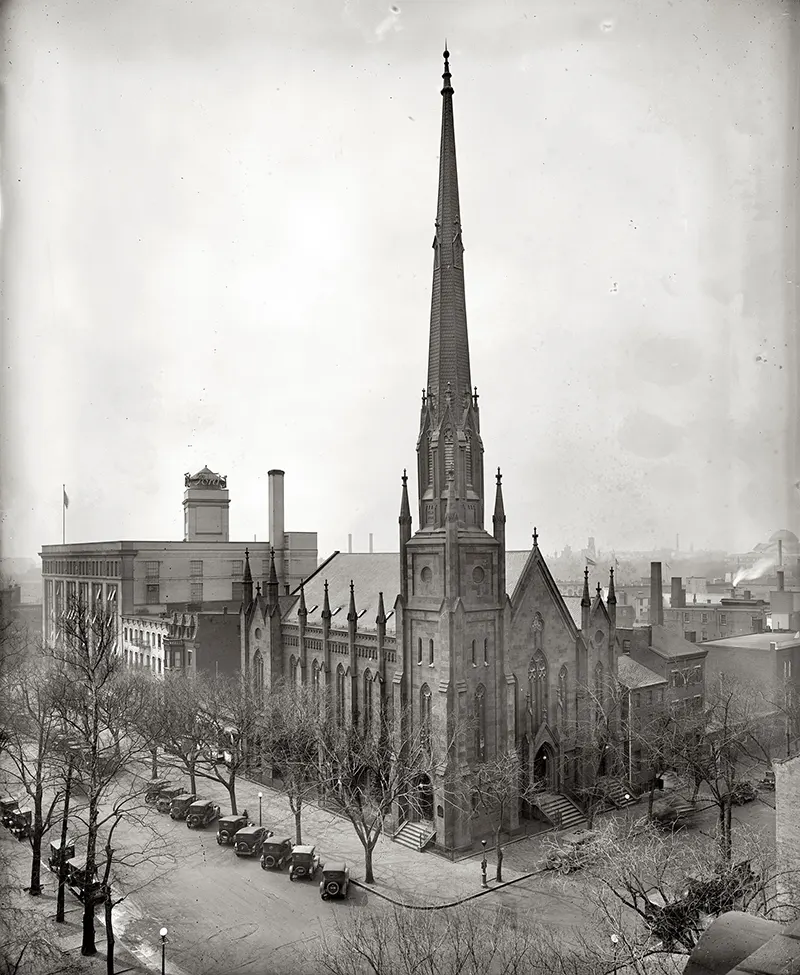

The years between 1880 and 1920 changed American cities as they went through a period of industrial progress, and to make room for more important buildings, many of the old ones were torn down. Moreover, in the post-war US, many structures that represented technical achievements just years before became outdated and were demolished. In this article, we have collected some of the most incredible buildings, train stations, offices, hotels, and many other architectural gems that no longer exist. At least, we have photographs to, somehow, enjoy these bygone landmarks. Pennsylvania Station (pictured above), often abbreviated to Penn Station, was a historic railroad station in New York City, named for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), its builder and original tenant. The station occupied an 8-acre (3.2 ha) plot bounded by Seventh and Eighth Avenues and 31st and 33rd Streets in Midtown Manhattan. The building was designed by McKim, Mead, and White and completed in 1910, enabling direct rail access to New York City from the south for the first time. Its head house and train shed were considered a masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style and one of the great architectural works of New York City. Starting in 1963, the above-ground head house and train shed were demolished, a loss that galvanized the modern historic preservation movement in the United States. Over the next six years, the below-ground concourses and waiting areas were heavily renovated, becoming the modern Penn Station, while Madison Square Garden and Pennsylvania Plaza were built above them. Mark Hopkins never got to see the mansion (pictured above).that he commissioned a pair of prominent architects to build for him and his wife atop San Francisco’s Nob Hill; the railroad magnate died before its completion in 1878. Sadly, we’ll the building is forever lost, the decadent Victorian palace burned down following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Beacon Towers (pictured above) was a Gilded Age mansion on Sands Point in the village of Sands Point on the North Shore of Long Island, New York. It was built from 1917 to 1918 for Alva Belmont, the ex-wife of William Kissam Vanderbilt and the widow, since 1908, of Oliver Belmont. Architectural historians have described the mansion as a pure Gothic fantasy, although it did owe some of its design elements to the alcázars of Spain and to depictions of castles in medieval illuminated manuscripts. The interior contained about 60 primary rooms and upwards of 140 in total. The entire structure was coated in smooth, gleaming white stucco. Eventually, the building was demolished in 1945. A new development was later built on the site, but scattered structural remains and the original gatehouse survived. The Chicago Federal Building in Chicago (pictured above), Illinois was constructed between 1898 and 1905 for the purpose of housing the Midwest’s federal courts, main post office, and other government bureaus. It stood in The Loop neighborhood on a block bounded by Dearborn, Adams, and Clark Streets, and Jackson Boulevard. The building was designed in the Beaux-Arts style by architect Henry Ives Cobb. The floorplan was a six-story Greek cross atop a two-story base with a raised basement. The building was capped by a dome at the crossing that held an additional eight floors of office space in its drum for a total of 16 floors. The gilt dome extended 100 ft (30 m) above the drum. It stood for sixty years until its quiet demolition in 1965. It was replaced with Mies van der Rohe’s modernist Kluczynski Federal Building—a far cry from the Beaux Arts extravagance of this lost treasure. demolished in 1965. The 45-floor Kluczynski Federal Building and Loop Postal Station, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, were built in its place. In 1896, Adolph Sutro rebuilt the Cliff House (pictured above) from the ground up as a seven-story Victorian chateau, called by some “the Gingerbread Palace”, below his estate on the bluffs of Sutro Heights. This was the same year work began on the Sutro Baths in a small cove immediately north of the restaurant. The baths included six of the large indoor swimming pools, a museum, a skating rink, and other pleasure grounds. Great throngs of San Franciscans arrived on steam trains, bicycles, carts, and horse wagons on Sunday excursions. Sutro purchased some of the collection of stuffed animals, artwork, and historic items from Woodward’s Gardens to display at both the Cliff House and Sutro Baths. The 1896 Cliff House survived the 1906 earthquake with little damage but burned to the ground on the evening of September 7, 1907. Built in 1874 on the site reserved for an opera house, the Old Cincinnati Library (pictured above) was a thing of wonder. With five levels of cast iron shelving, a fabulous foyer, checkerboard marble floors, and an atrium lit by a skylight ceiling, the place was breathtaking. Unfortunately, that magnificent maze of books is now lost forever. In January of 1955, a new contemporary library opened at 800 Vine Street. The old building was sold to Leyman Corp for about $100,000 today, and by June that year, the magnificent library was razed. The Schiller Theater Building (pictured above) was designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler of the firm Adler & Sullivan for the German Opera Company. At the time of its construction, it was among the tallest buildings in Chicago. Its centerpiece was a 1300-seat theater, which is considered by architectural historians to be one of the greatest collaborations between Adler and Sullivan. The theater changed its name and duties over the following decades. It was briefly known as the Dearborn Theater from 1898 to 1903, until finally settling on the name Garrick Theater. After German investors backed out of the project in the late 1890s, it ceased its German performances, and exhibited touring stage shows. In the 1930s the theater was acquired by Balaban & Katz who converted it into a movie theater. It became a television studio in 1950 and returned to screening movies in 1957. After a long decline that began in the 1930s, the Garrick was razed early in 1961 and replaced with a parking structure. The demolition instigated a large outcry and is considered to be one of the first wide-scale preservation efforts in Chicago. The Singer Building (pictured above) was an office building and early skyscraper in Manhattan, New York City. The headquarters of the Singer Manufacturing Company, it was at the northwestern corner of Liberty Street and Broadway in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. Frederick Gilbert Bourne, leader of the Singer Company, commissioned the building, which architect Ernest Flagg designed in multiple phases from 1897 to 1908. The building’s architecture contained elements of the Beaux-Arts and French Second Empire styles. With a roof height of 612 feet (187 m), the Singer Tower was the tallest building in the world from 1908 to 1909, when it was surpassed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower. The base occupied the building’s entire land lot; the tower’s floors took up just one-sixth of that area. Despite being regarded as a city icon, the Singer Building was razed between 1967 and 1969 to make way for One Liberty Plaza, which had several times more office space than the Singer Tower. At the time of its destruction, the Singer Building was the tallest building ever to be demolished. The Detroit City Hall (pictured above) was the seat of government for the city of Detroit, Michigan from 1871–1961. The building sat on the west side of Campus Martius bounded by Griswold Street to the west, Michigan Avenue to the north, Woodward Avenue to the east, and Fort Street to the south where One Kennedy Square stands, today. It stood three stories tall, and included a partially raised basement level and an attic level. An observation level was at the top of the bell tower. The Detroit City Hall was designed mainly in the Italian Renaissance revival architectural style, but during the design process, a French Second Empire mansard roof was added. It measured 200 feet in length by 90 feet in width, and the tower rose 180 feet tall. It was faced with mainly cream-colored Amherst Sandstone. The building took 10 years to complete, mostly due to restrictions of material during the Civil War, but much had to do with city politicians fighting over the bids and contracts. The building’s demolition concluded in September 1961 with the clock tower being the last piece of the building to be razed. Young’s Million Dollar Pier (pictured above) opened on July 26, 1906, with a length of 1,900 feet (580 m). It was owned by Associated Realties Company, a corporation that was owned by Young and Crossan. The Million Dollar Pier had what was claimed to be the world’s largest ballroom, as well as a Hippodrome Theater with 4,000 seats, Exhibit Hall, Greek Temple, aquarium and a roller skating rink. Hotel Astor (pictured above) was a hotel on Times Square in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Built in 1905 and expanded in 1909–1910 for the Astor family, the hotel occupied a site bounded by Broadway, Shubert Alley, and 44th and 45th Streets. Architects Clinton & Russell designed the hotel as an 11-story Beaux-Arts edifice with a mansard roof. It contained 1,000 guest rooms, with two more levels underground for its extensive “backstage” functions, such as the wine cellar. The hotel was developed as a successor to the Waldorf-Astoria. Hotel Astor’s success triggered the construction of the nearby Knickerbocker Hotel by other members of the Astor family two years later. The building was razed in 1967 to make way for the high-rise office tower One Astor Plaza. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress / Pinterest) Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe