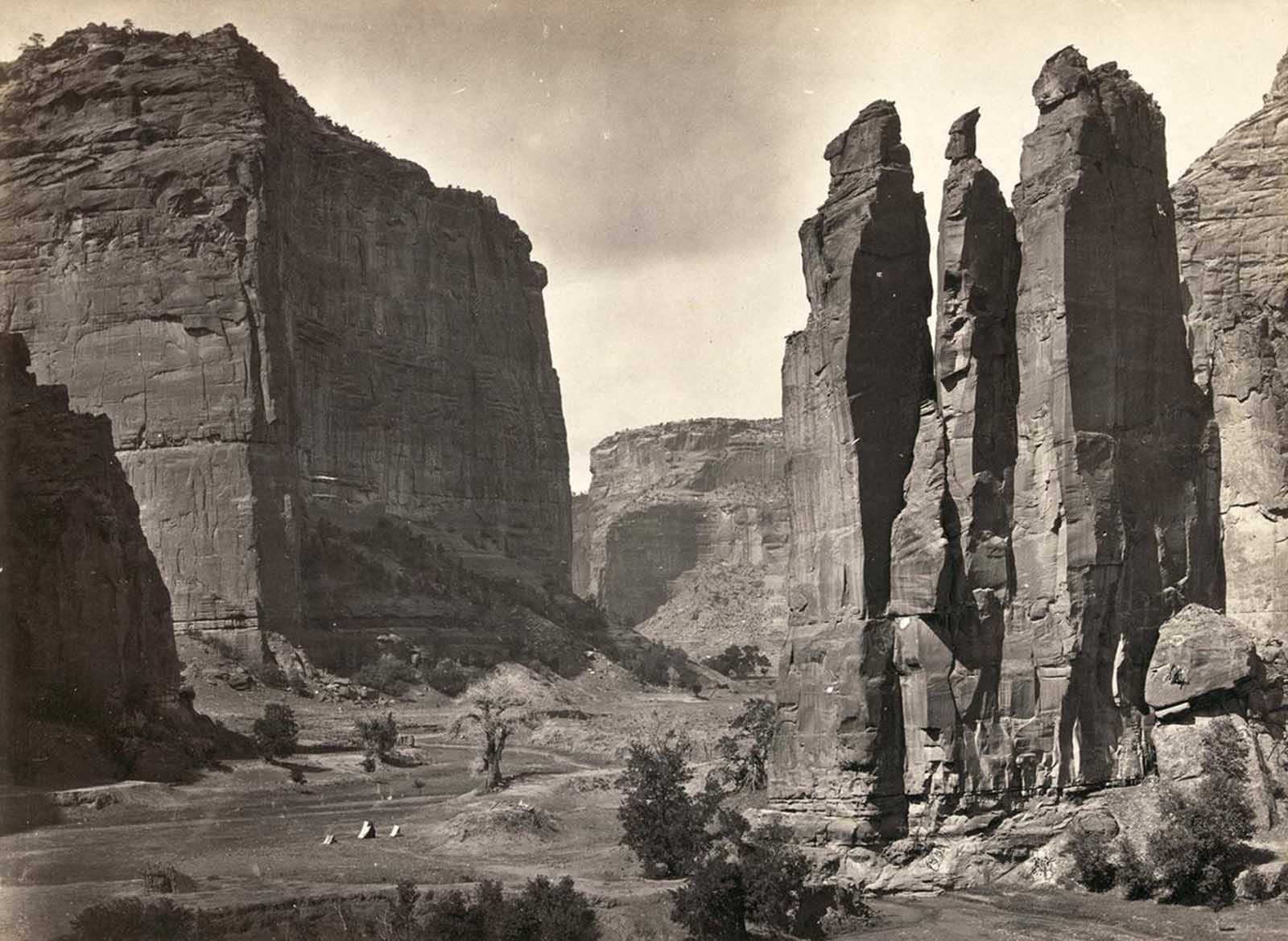

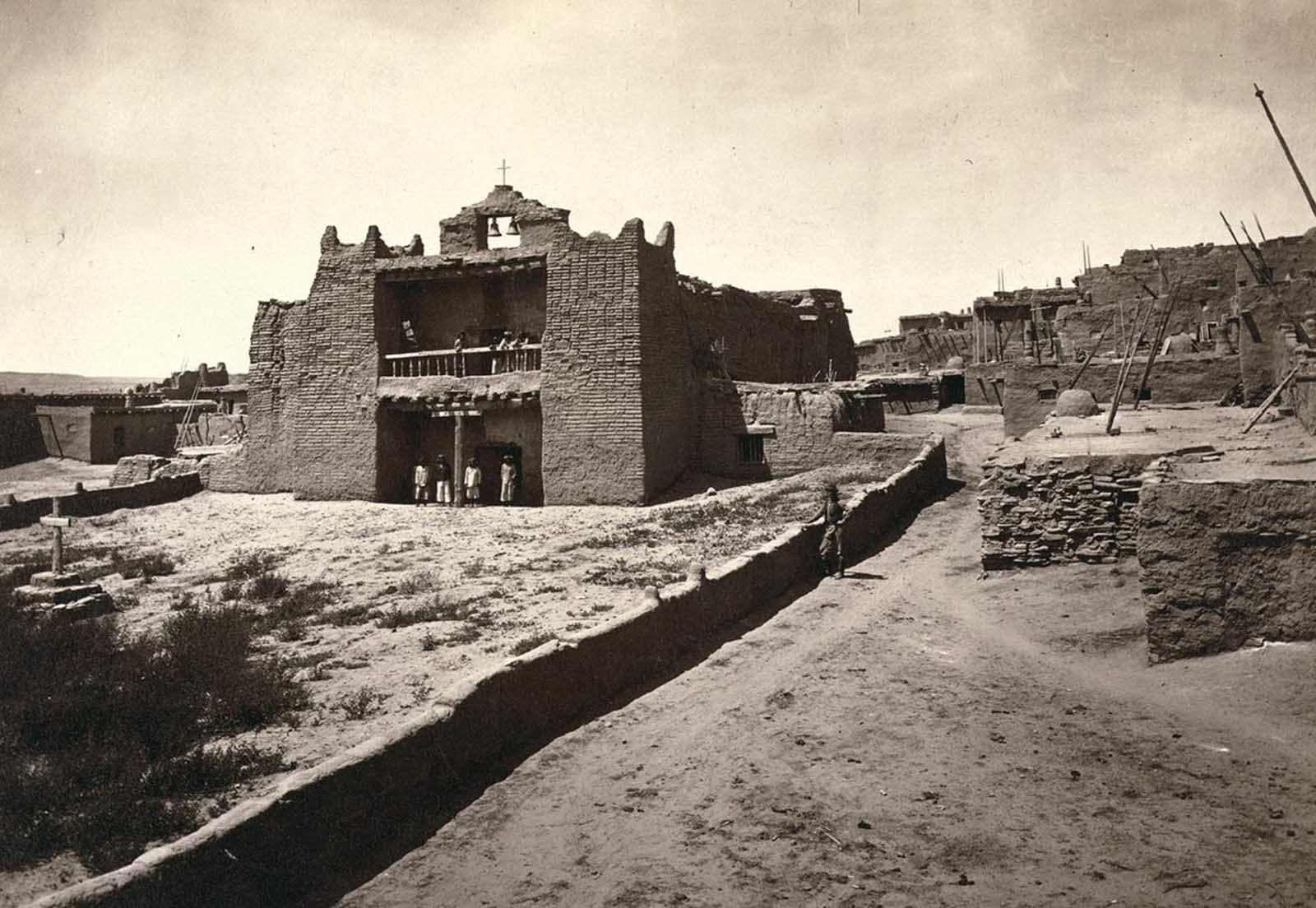

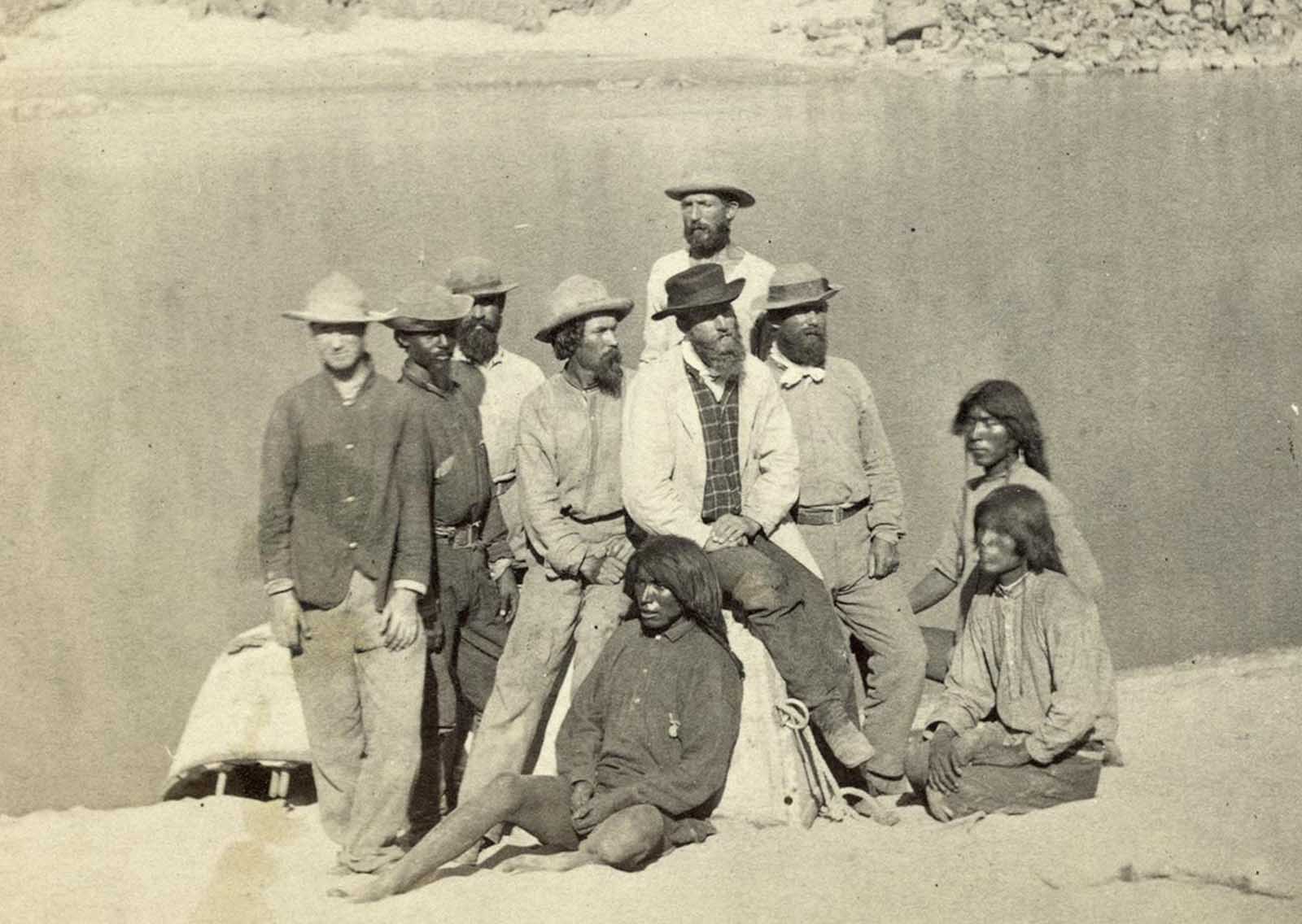

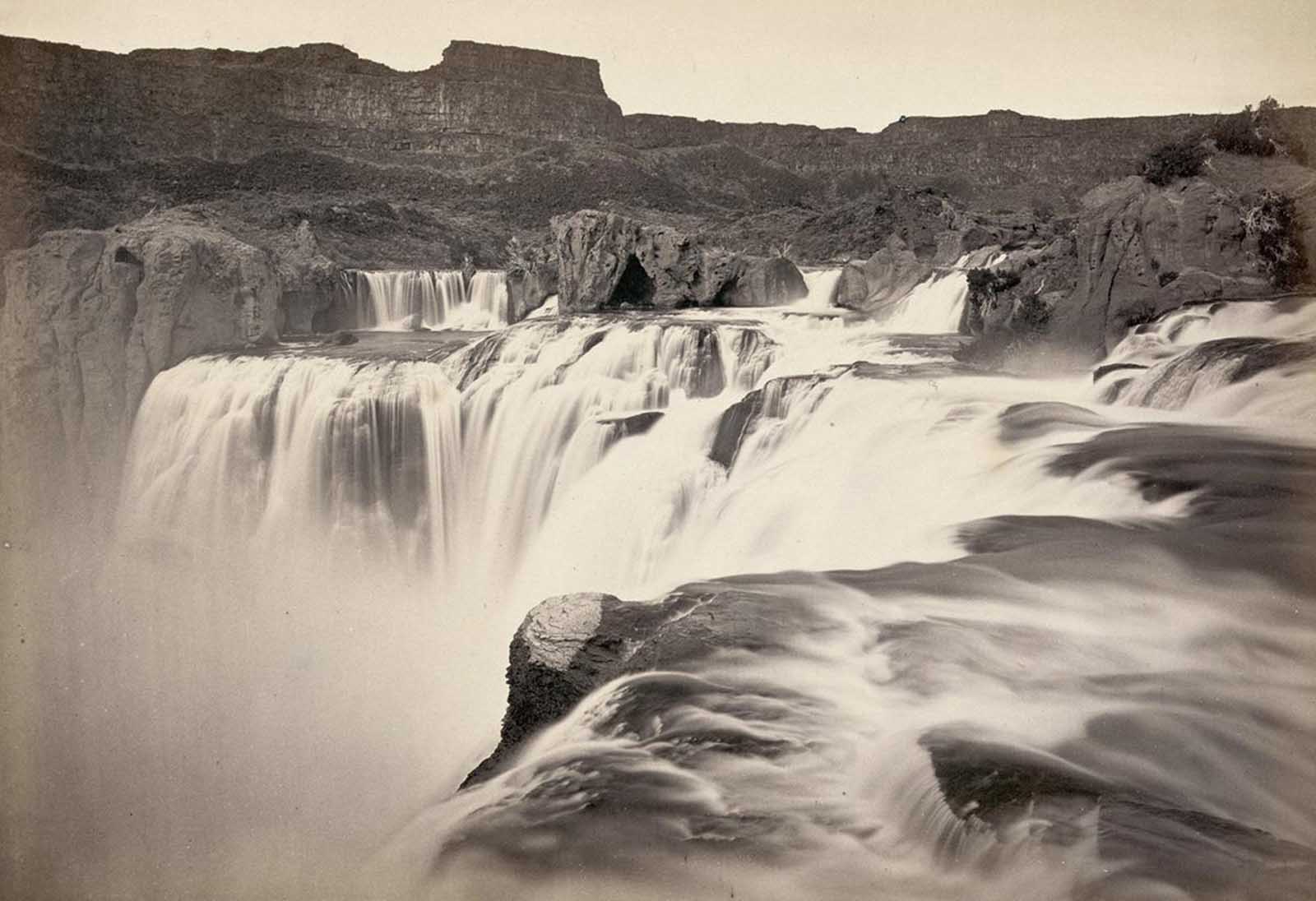

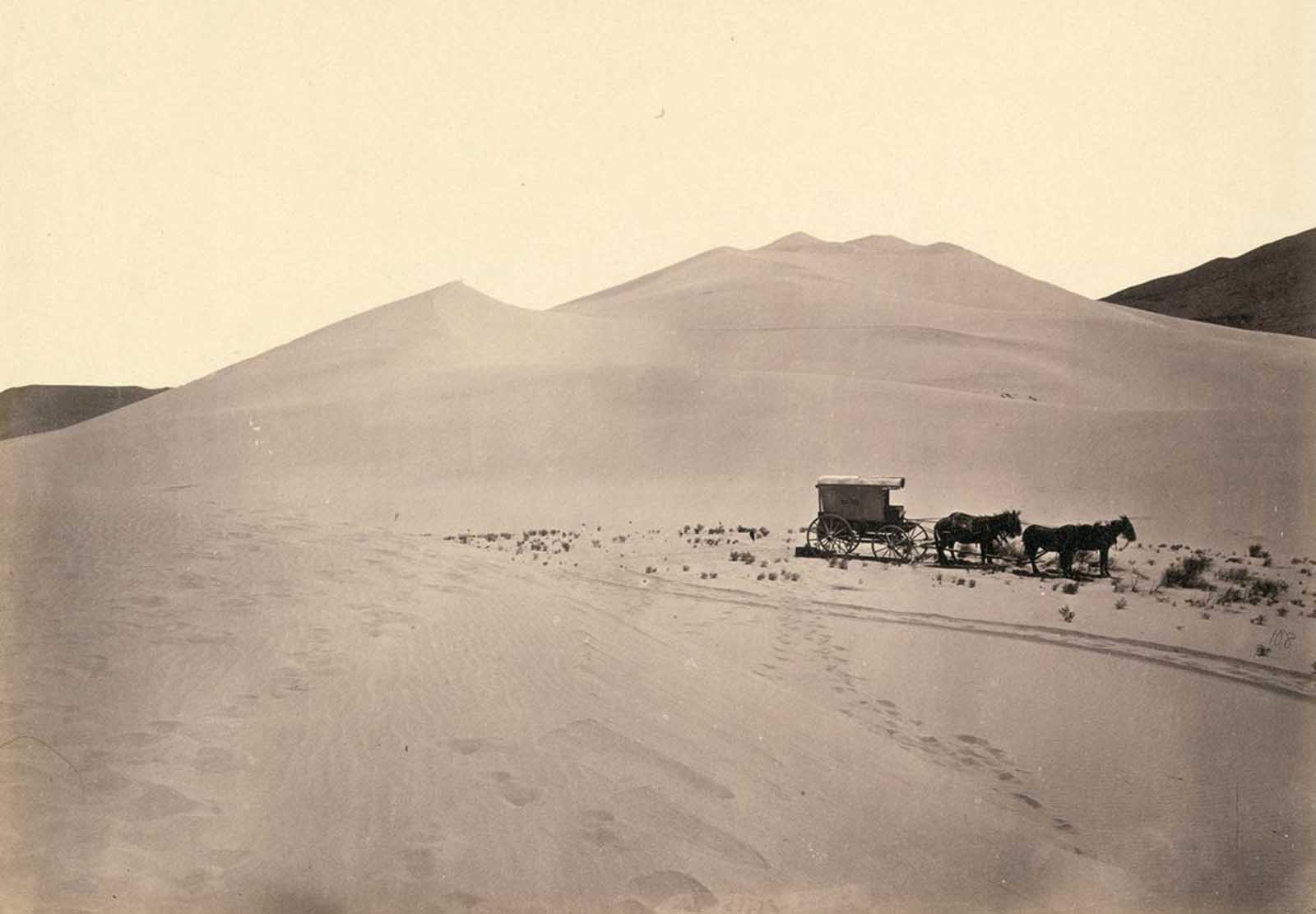

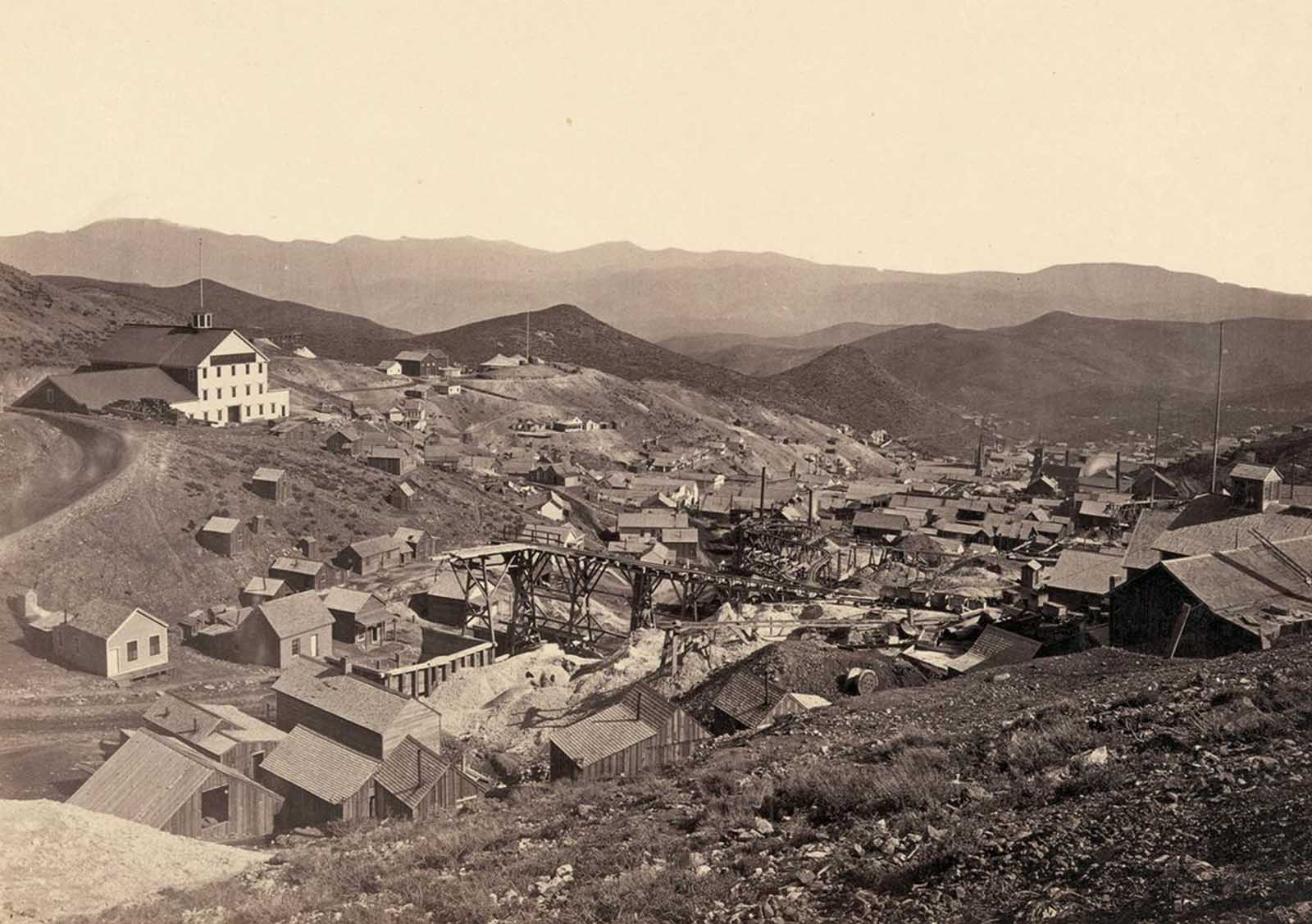

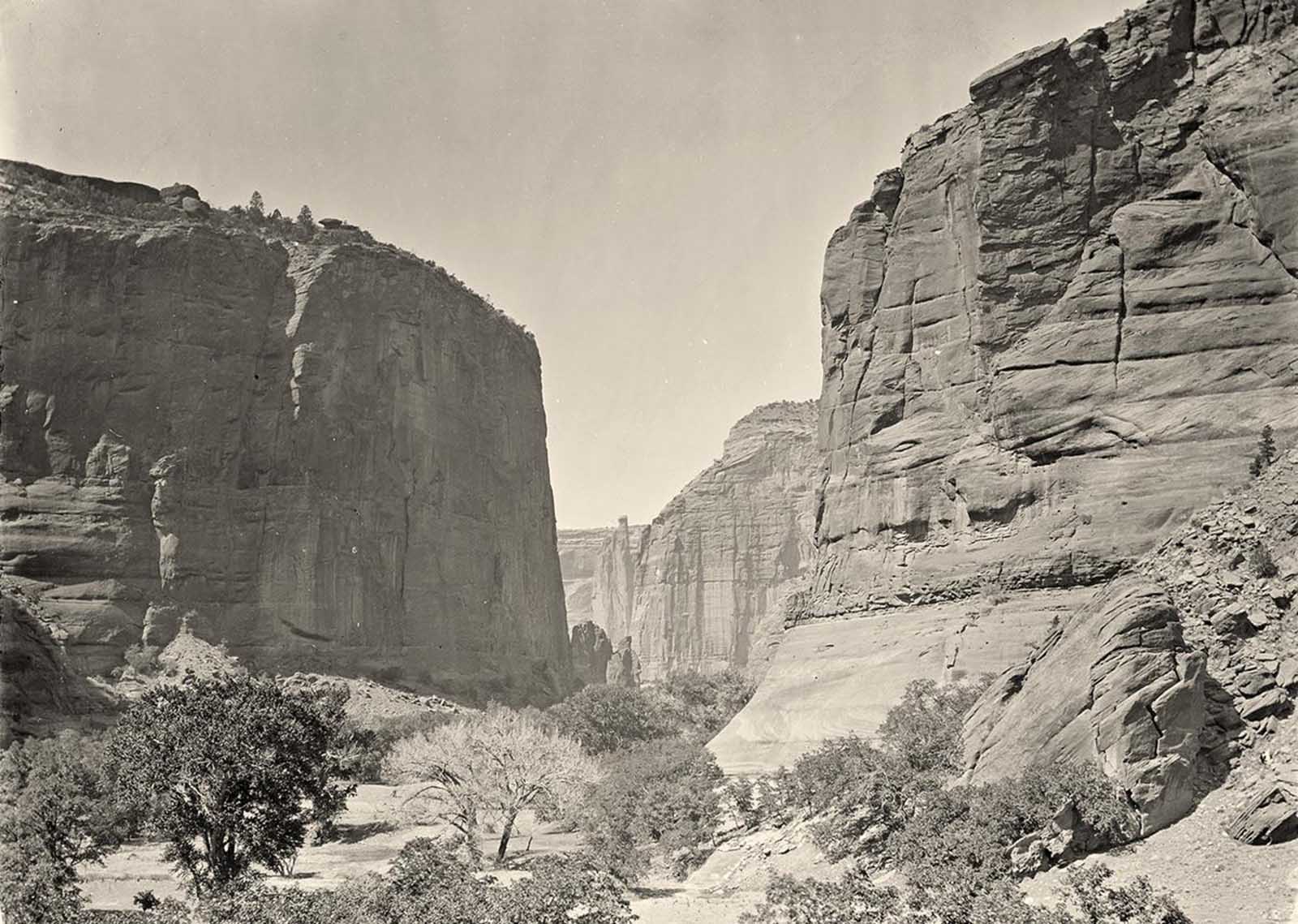

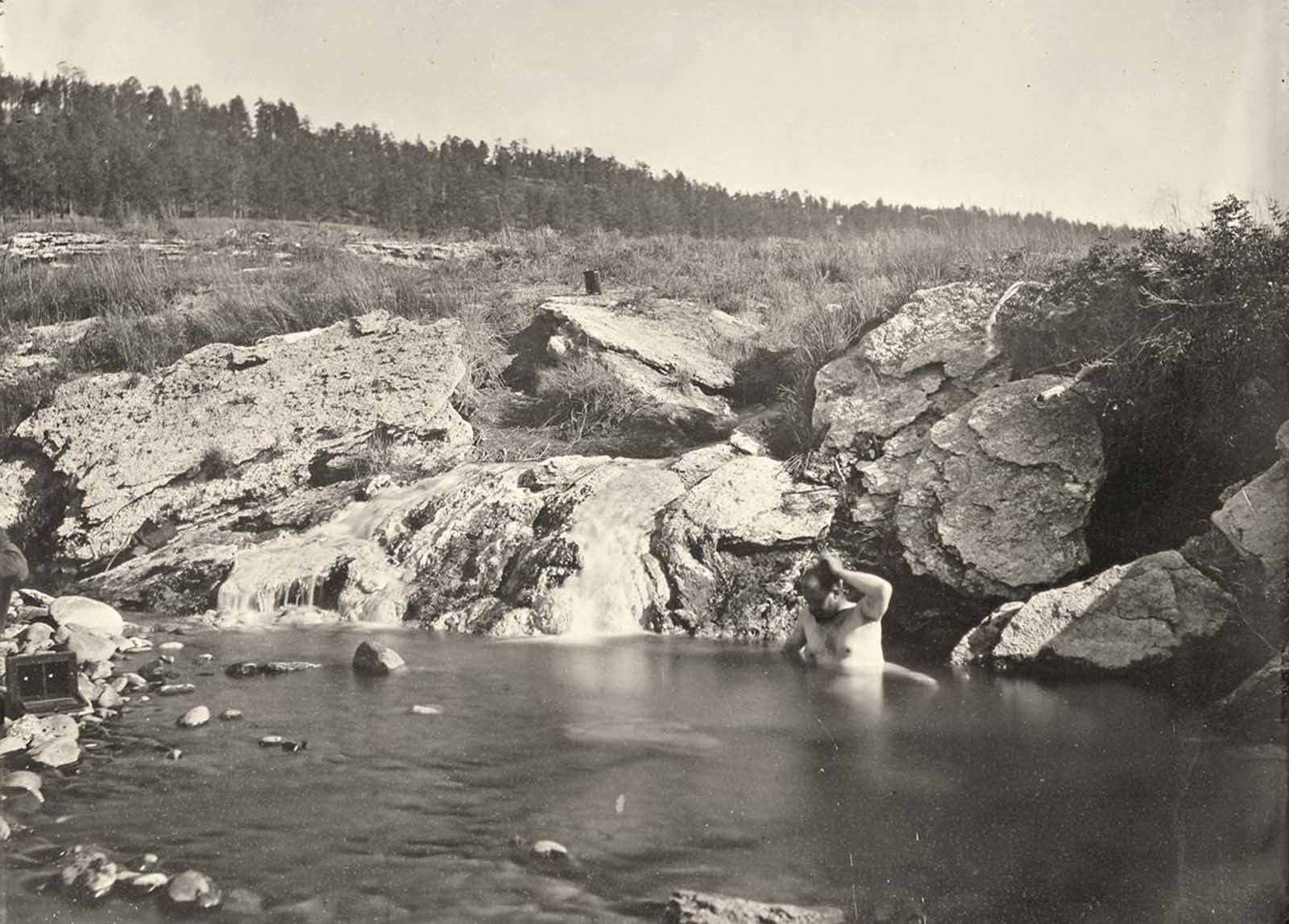

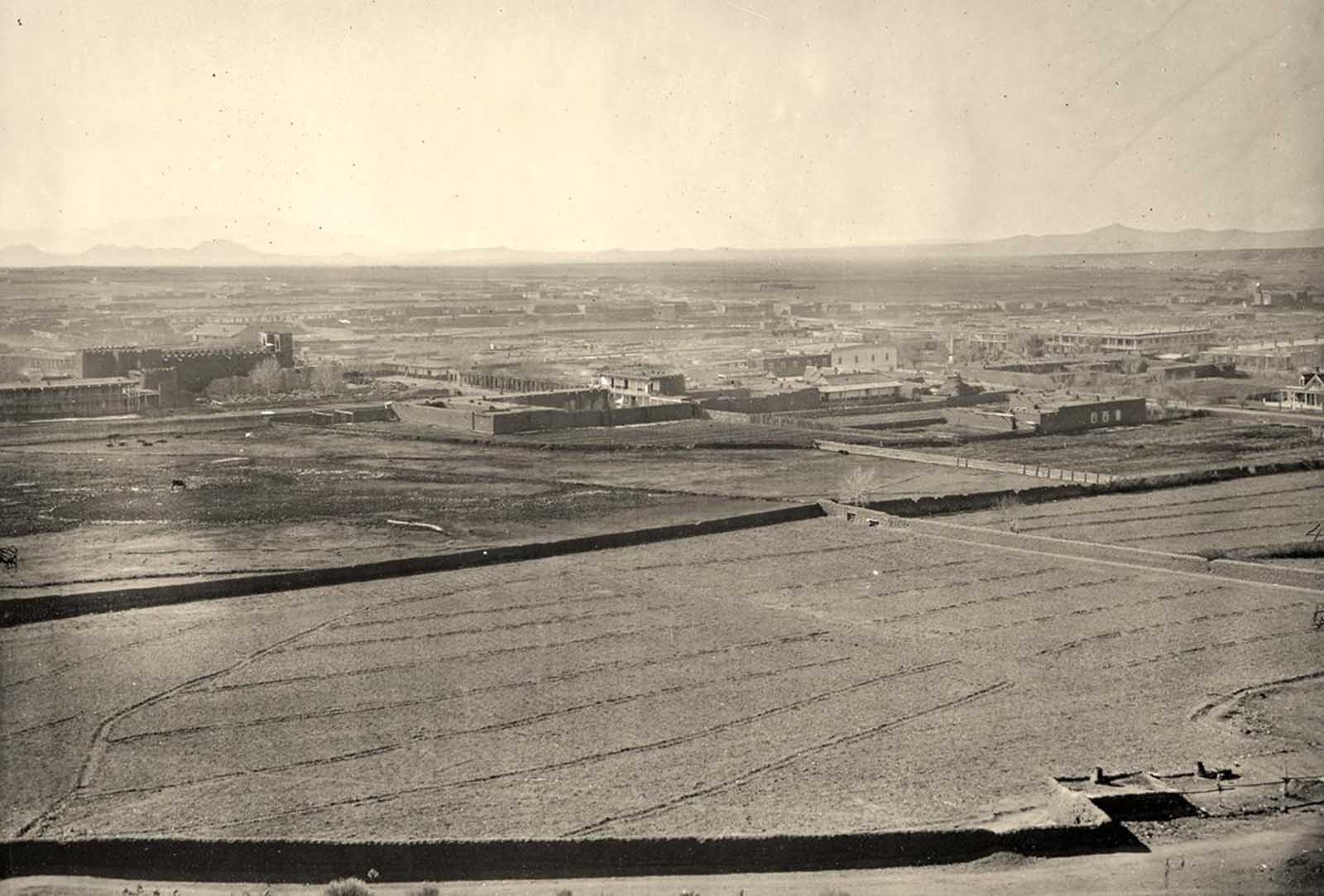

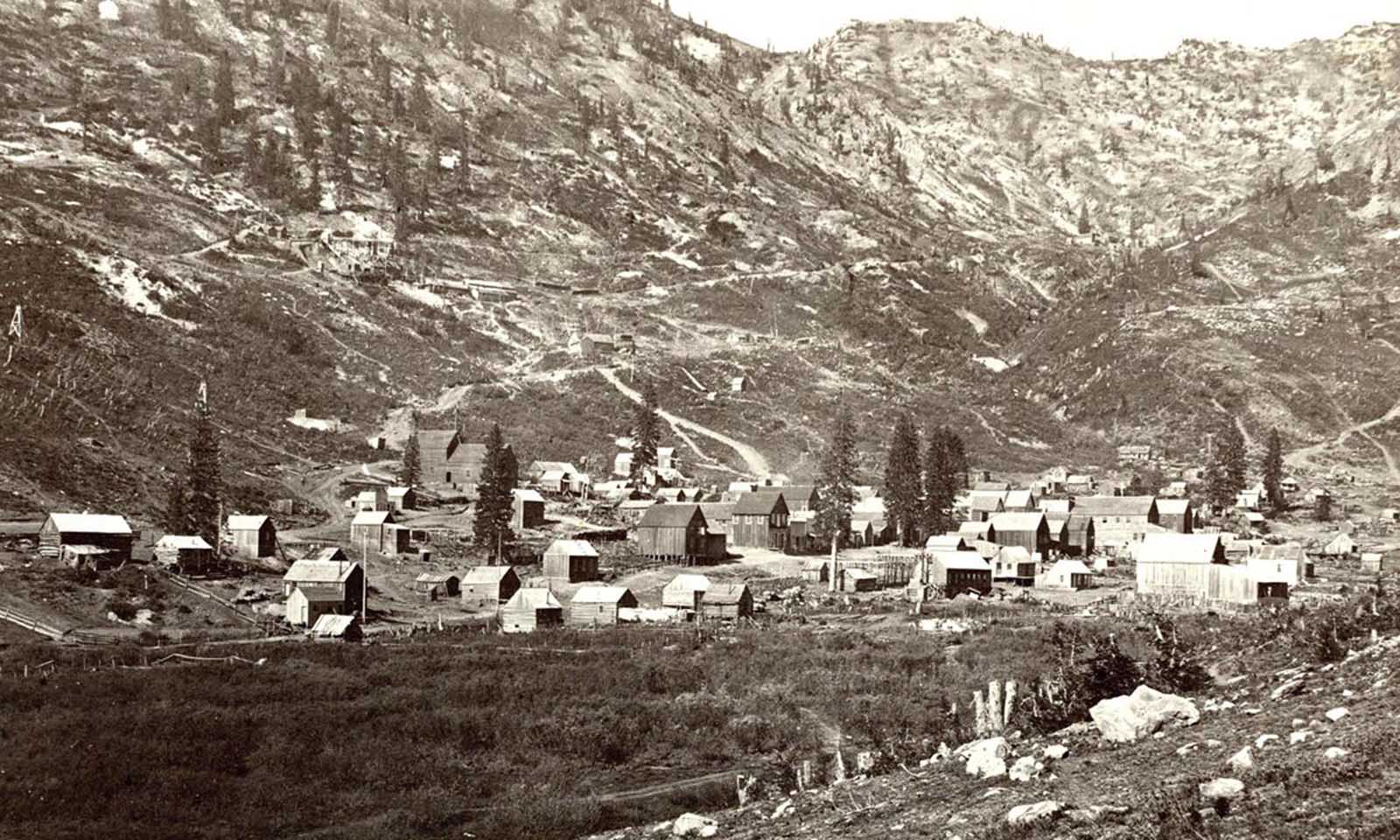

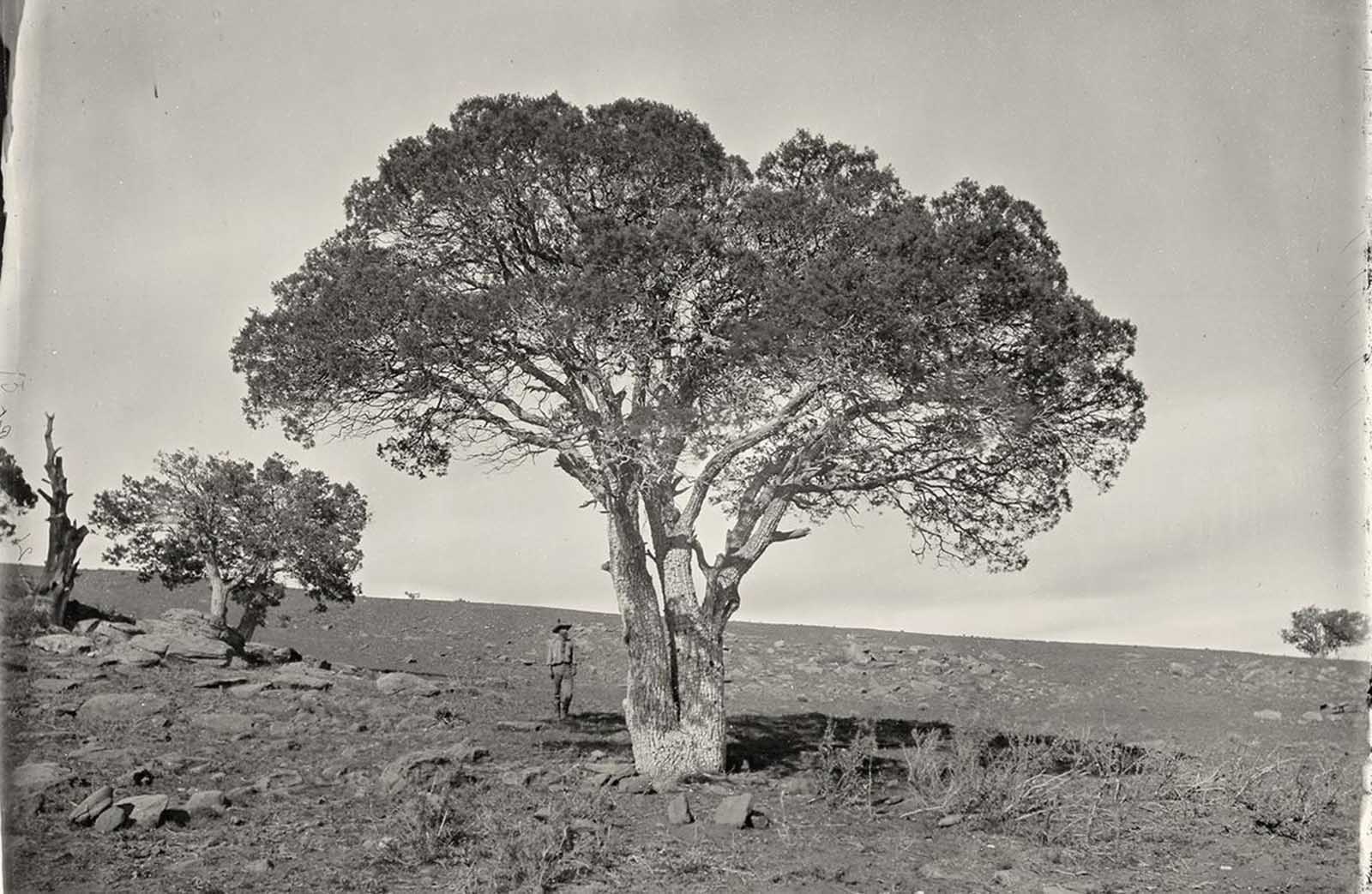

After covering the U.S. Civil War, O’Sullivan was the official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel under Clarence King, an expedition organized by the federal government to help document the new frontiers in the American West. The expedition began at Virginia City, Nevada, where he photographed the mines and worked eastward. His job was to photograph the West to attract settlers. In so doing, he became one of the pioneers in the field of geophotography. O’Sullivan’s pictures were among the first to record the prehistoric ruins, Navajo weavers, and pueblo villages of the Southwest. In contrast to the Asian and Eastern landscape fronts, the subject matter he focused on was a new concept. It involved taking pictures of nature as an untamed, pre-industrialized land without the use of landscape painting conventions. Above all, O’Sullivan captured, for the first time on film, the natural beauty of the American West. The completion of the railroads to the West following the Civil War opened up vast areas of the region to settlement and economic development. White settlers from the East poured across the Mississippi to mine, farm, and ranch. African-American settlers also came West from the Deep South, convinced by promoters of all-black Western towns that prosperity could be found there. Chinese railroad workers further added to the diversity of the region’s population. The settlements from the East transformed the Great Plains. The huge herds of American bison that roamed the plains were virtually wiped out, and farmers plowed the natural grasses to plant wheat and other crops. The cattle industry rose in importance as the railroad provided a practical means for getting the cattle to market. The loss of the bison and the growth of white settlement drastically affected the lives of the Native Americans living in the West. In the conflicts that resulted, the American Indians, despite occasional victories, seemed doomed to defeat by the greater numbers of settlers and the military force of the U.S. government. By the 1880s, most American Indians had been confined to reservations, often in areas of the West that appeared least desirable to white settlers. The cowboy became the symbol for the West of the late 19th century, often depicted in popular culture as a glamorous or heroic figure. The stereotype of the heroic white cowboy is far from true, however. The first cowboys were Spanish vaqueros, who had introduced cattle to Mexico centuries earlier. Black cowboys also rode the range. Furthermore, the life of the cowboy was far from glamorous, involving long, hard hours of labor, poor living conditions, and economic hardship. The myth of the cowboy is only one of many myths that have shaped our views of the West in the late 19th century. Recently, some historians have turned away from the traditional view of the West as a frontier, a “meeting point between civilization and savagery” in the words of historian Frederick Jackson Turner. They have begun writing about the West as a crossroads of cultures, where various groups struggled for property, profit, and cultural dominance. Think about these differing views of the history of the West as you examine the documents in this collection. (Photo credit: Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe