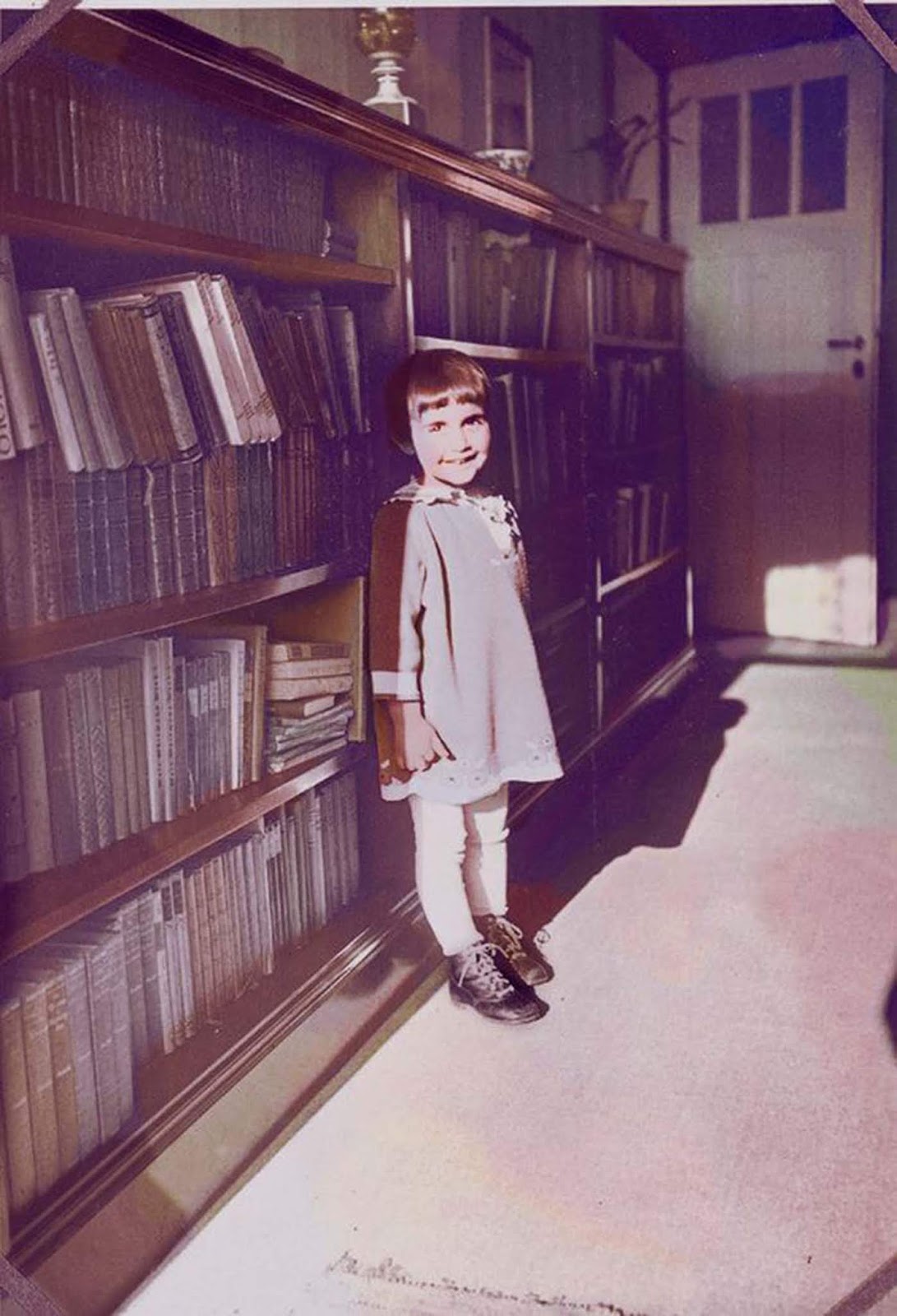

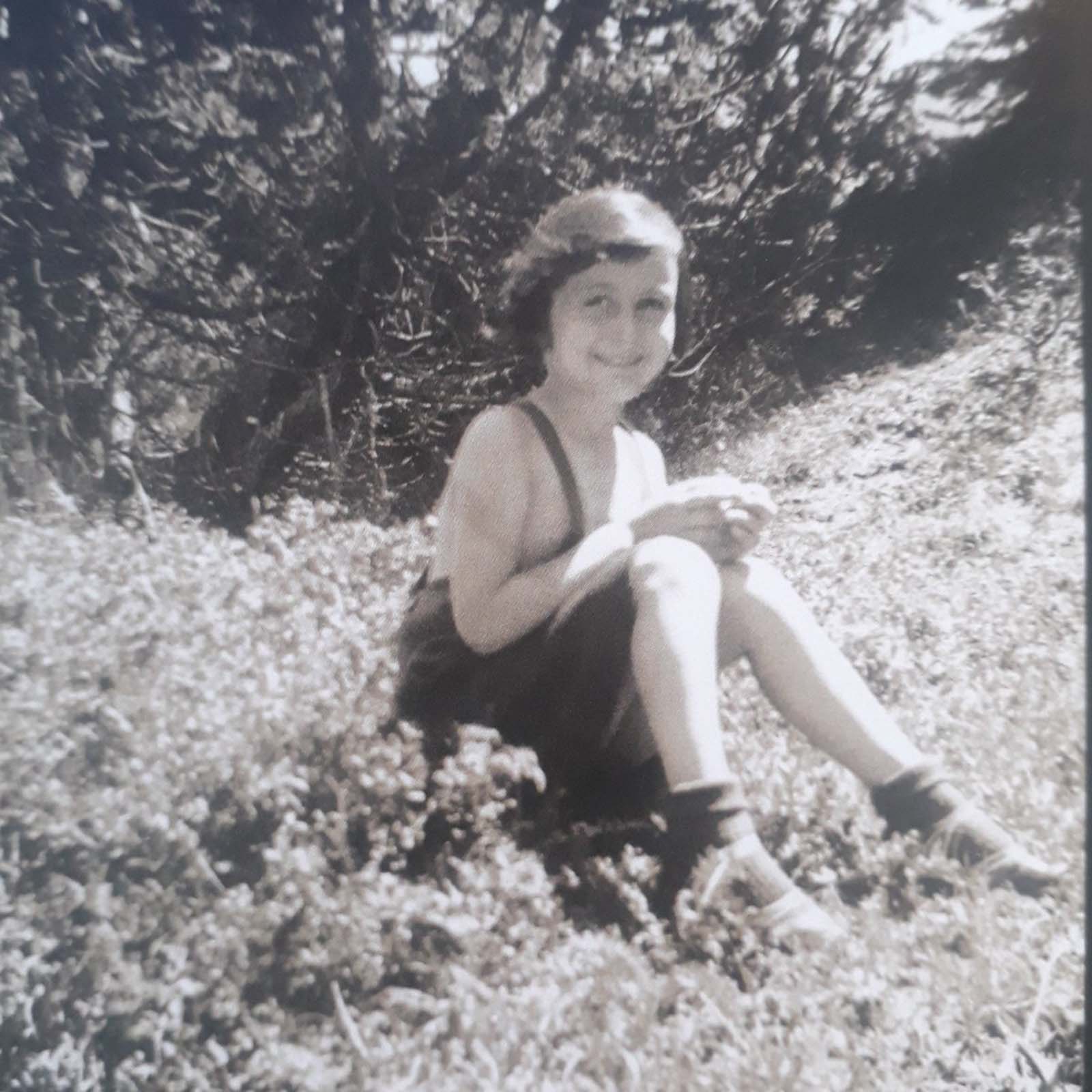

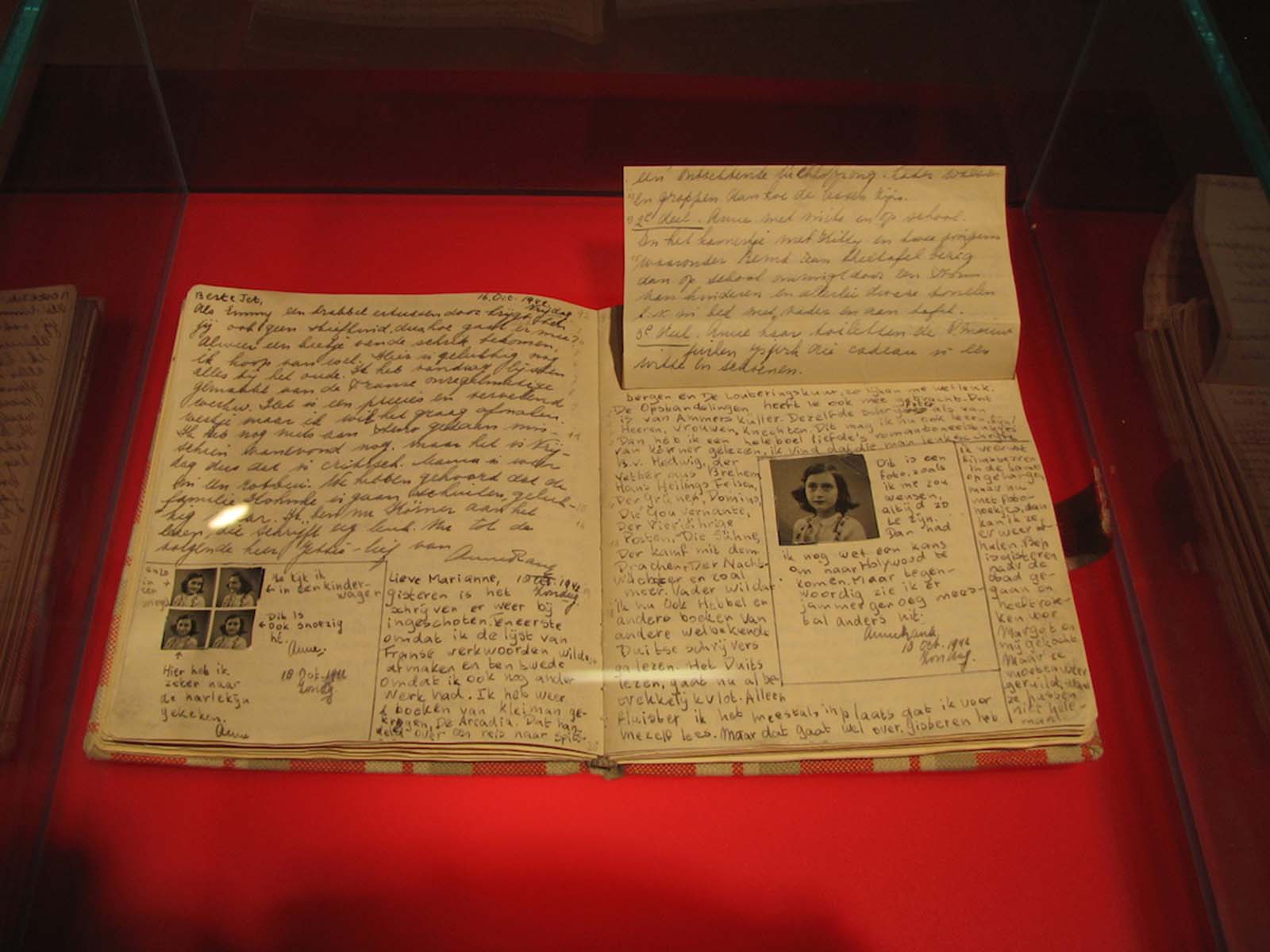

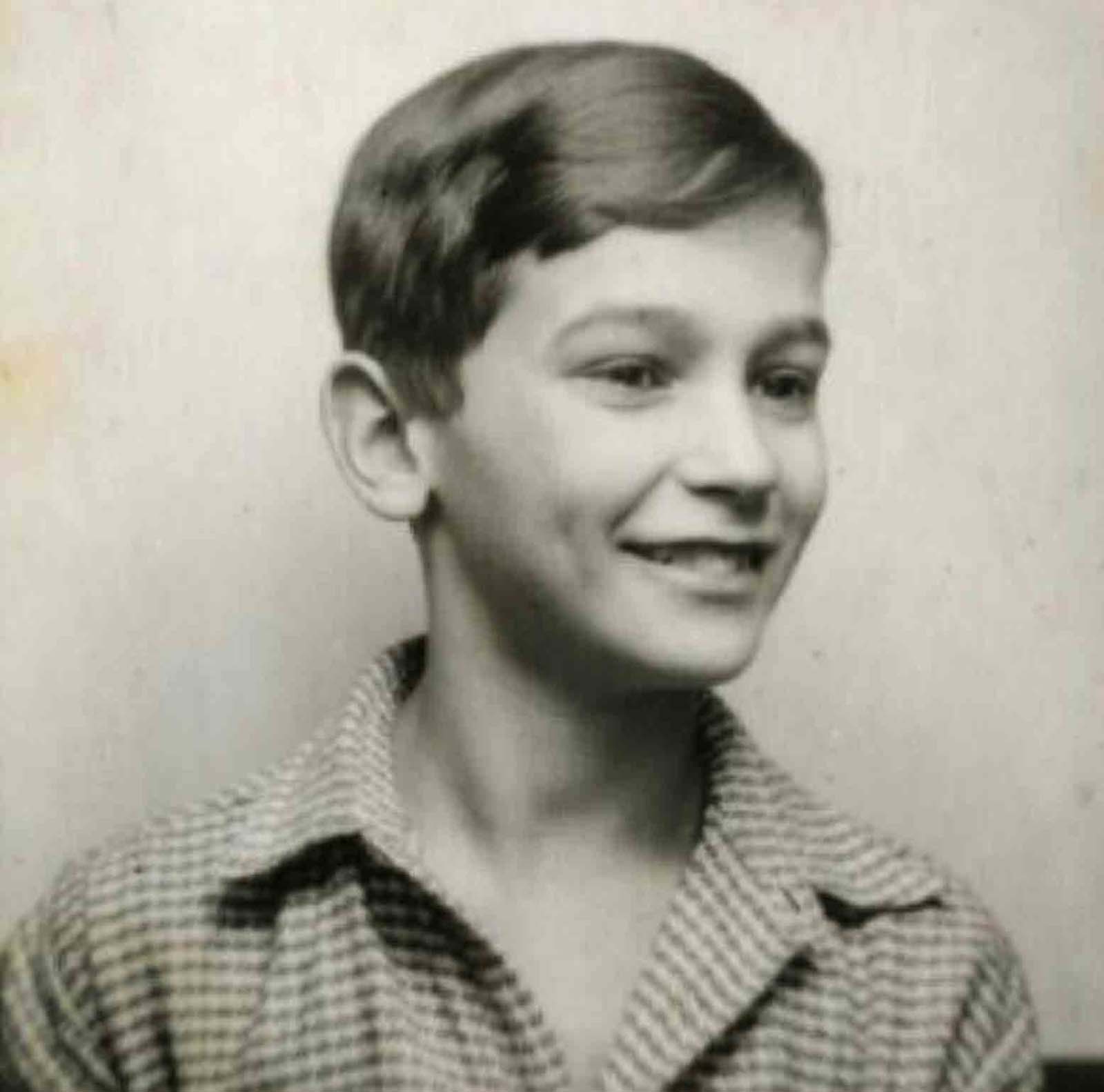

Born in Frankfurt, Germany, she lived most of her life in or near Amsterdam, Netherlands, having moved there with her family at the age of four and a half when the Nazis gained control over Germany. Born a German national, she lost her citizenship in 1941 and thus became stateless. By May 1940, the Franks were trapped in Amsterdam by the German occupation of the Netherlands. As persecutions of the Jewish population increased in July 1942, the Franks went into hiding in some concealed rooms behind a bookcase (known as the Annex) in the building where Anne’s father, Otto Frank, worked. While hiding Anne kept a diary she had received as a birthday present and wrote in it regularly. The plan worked beautifully for over two years. On the morning of 4 August 1944, though, there was a knock on the door, and it wasn’t gentle. An informer who was never identified had sent the police to the Annex. The police were led by SS-Oberscharführer Karl Silberbauer of the Sicherheitsdienst. The group of German uniformed police (Grüne Polizei) took the Franks to headquarters. After some shuffling around, they wound up at the Westerbork transit camp. The war was winding down rapidly – the Allies were already in Brussels, Belgium – but there was time for one last train to Auschwitz. On 3 September 1944, the group was deported on what would be the last transport from Westerbork to Auschwitz concentration camp. All of the Franks survived the initial screening – failing meant death in the gas showers – but that was only the start of their troubles. About a month later, Anne and Margot were transferred to another death camp, Bergen-Belsen. Edith (her mother) stayed behind at Auschwitz and soon died. Anne and Margot wound up at Bergen-Belsen. They survived through a miserable winter, but not long after. The sisters both died in March or April 1945. Food was scarce and epidemics raged through the camps in unheated dormitories. Bergen-Belsen was liberated on April 15, 1945, by British troops, but it was too late for Anne Frank. Otto Frank survived. Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl were two of the employees who had been helping to shelter the Franks. They found some papers that the Franks had left behind and kept them in safekeeping. When Otto Frank came by, they gave him the papers. Looking them over, Otto recalled that Anne had kept a diary. It was a very detailed and comprehensive diary. It ended right before the Franks were arrested. The diary was published in Germany and France in 1950, and in England in 1952. At first, it attracted little attention. For some reason, the Japanese were the first to really recognize Anne Frank as a cultural figure of great significance. Her fame grew from there. “The Diary of Anne Frank,” as it is known in the publishing world, has only grown in popularity over the subsequent decades. It is considered a key part of the curriculum of schools around the world. It is especially revered in Holland. The Anne Frank House opened to the public on 3 May 1960 after Otto Frank went to great lengths to preserve it for history. It consists of his Opekta warehouse and offices and the Achterhuis where the Annex was located. It remains open to the public and is a top tourist attraction in Amsterdam. Clearly, Anne Frank demonstrated the power of the pen and never will be forgotten. The story of Silberbauer is important. Some might think that he was a cruel and inhuman monster who should have been hung outright as soon as he was identified as the man who arrested Anne Frank. That is an understandable feeling, based on the injustices of the world and the barbarity of the system in which he served. Simon Wiesenthal, the famed war criminal hunter, went to great lengths to find Silberbauer. He finally did. Silberbauer had returned to Austria and, after a jail sentence by the Russians due to his brutal interrogations of Communists, had been released. After many years of working to infiltrate possible terrorist groups for the government (basically as a continuation of his sentence), Silberbauer was rehabilitated and set free. He rejoined the Viennese police force, which is where Wiesenthal found him many years after the war. At this point, Anne Frank had become a world celebrity. The play and diary and film were all worldwide hits. Upon learning of his past, the Austrian authorities were aghast. Silberbauer was suspended by the police force pending an investigation of what he had done during the war. It was a decisive moment in the life of Silberbauer, who freely admitted to having arrested Frank and remembered the incident with clarity. There was a media outcry against him. People hated him for what he had done. Silberbauer admitted everything. He did not have any information about who had betrayed the Franks and simply stated that he had done his job without rancor. He had been a tiny cog in an immense wheel of injustice. Incredibly, Otto Frank stepped forward on his behalf and testified to the court that Silberbauer had acted correctly and without cruelty during the arrest. Silberbauer, he stated, even had done his job with some degree of courtesy. That statement implies nothing about Silberbauer or his intelligence, morals or ethics, or anything else aside from that limited point. Otto Frank figured that the unknown person who had betrayed them was the malefactor, not Silberbauer, who was simply doing as ordered. Mr. Frank was not joined by many in this assessment, but his opinion was decisive in Silberbauer’s fate. Based on Otto Frank’s ability to be fair and speak up on Silberbauer’s behalf, the Dutch and Austrian courts cleared Silberbauer of any wrongdoing in the incident. He had just been doing his job, they concluded. Silberbauer was reinstated to the Vienna police force and allowed to continue with his life unmolested, probably grateful that the whole thing had been hashed out and resolved. He died in Vienna about ten years later, in 1972, aged 61. (Photo credit: National Archives / Getty Images). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe