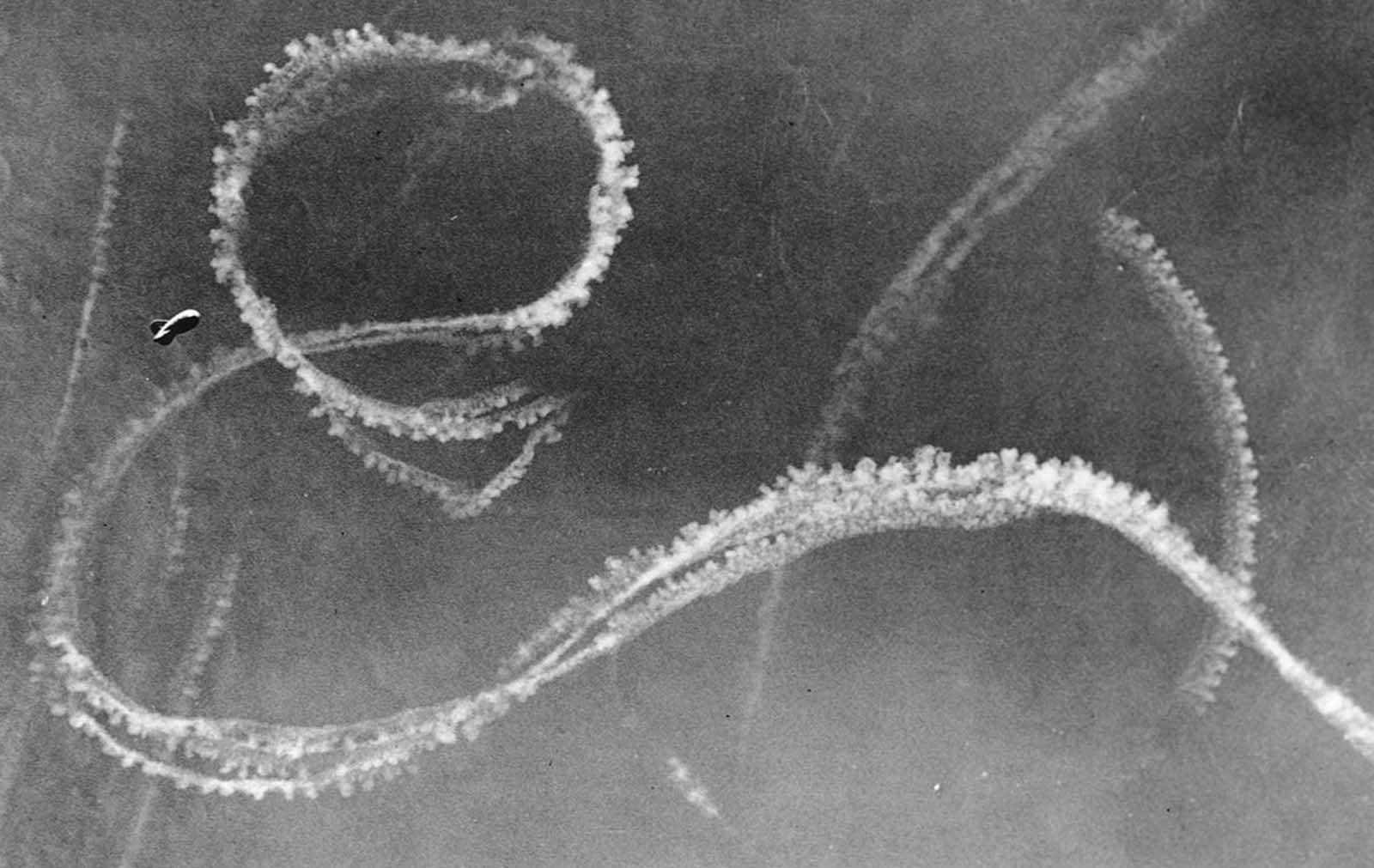

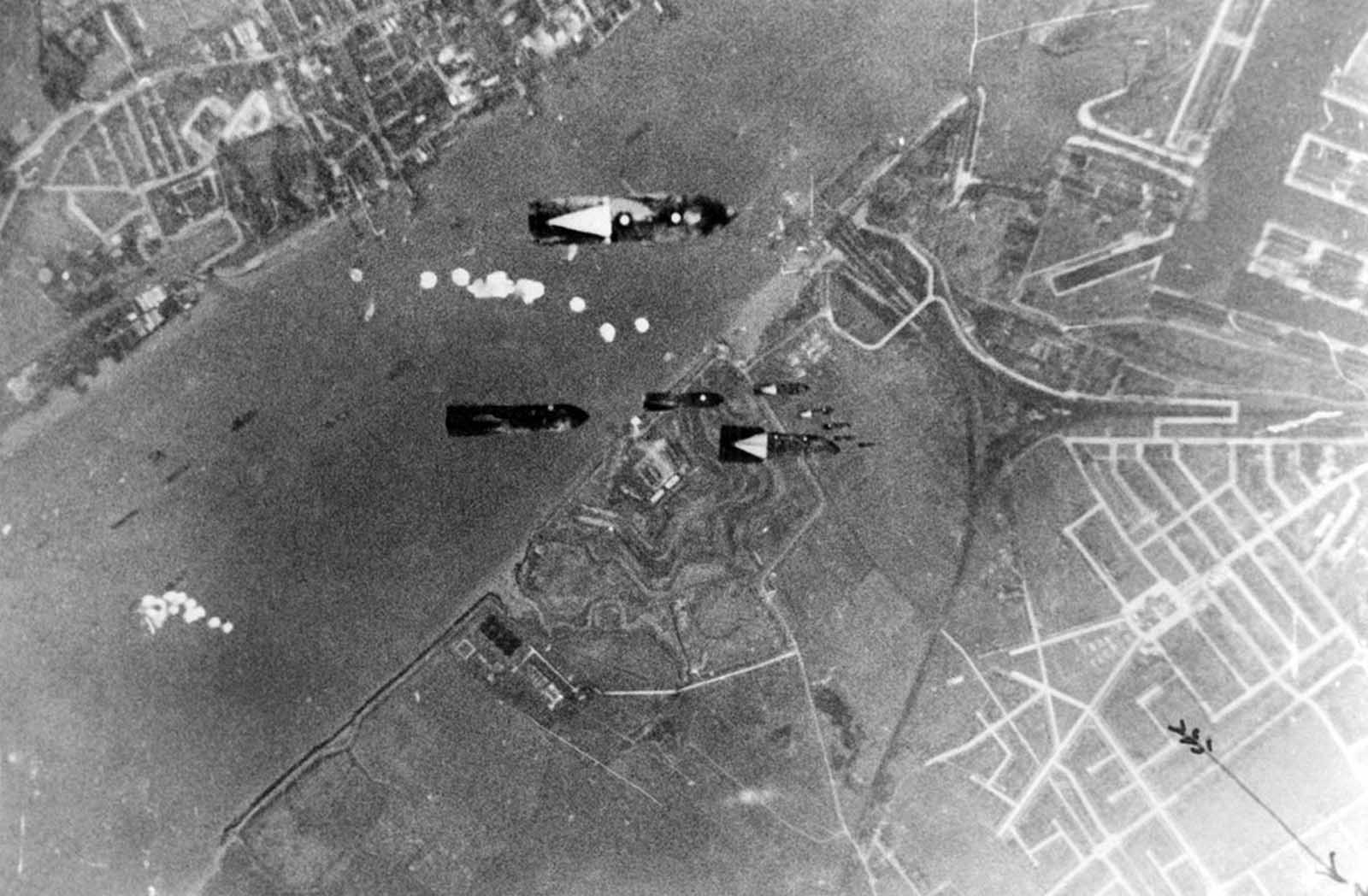

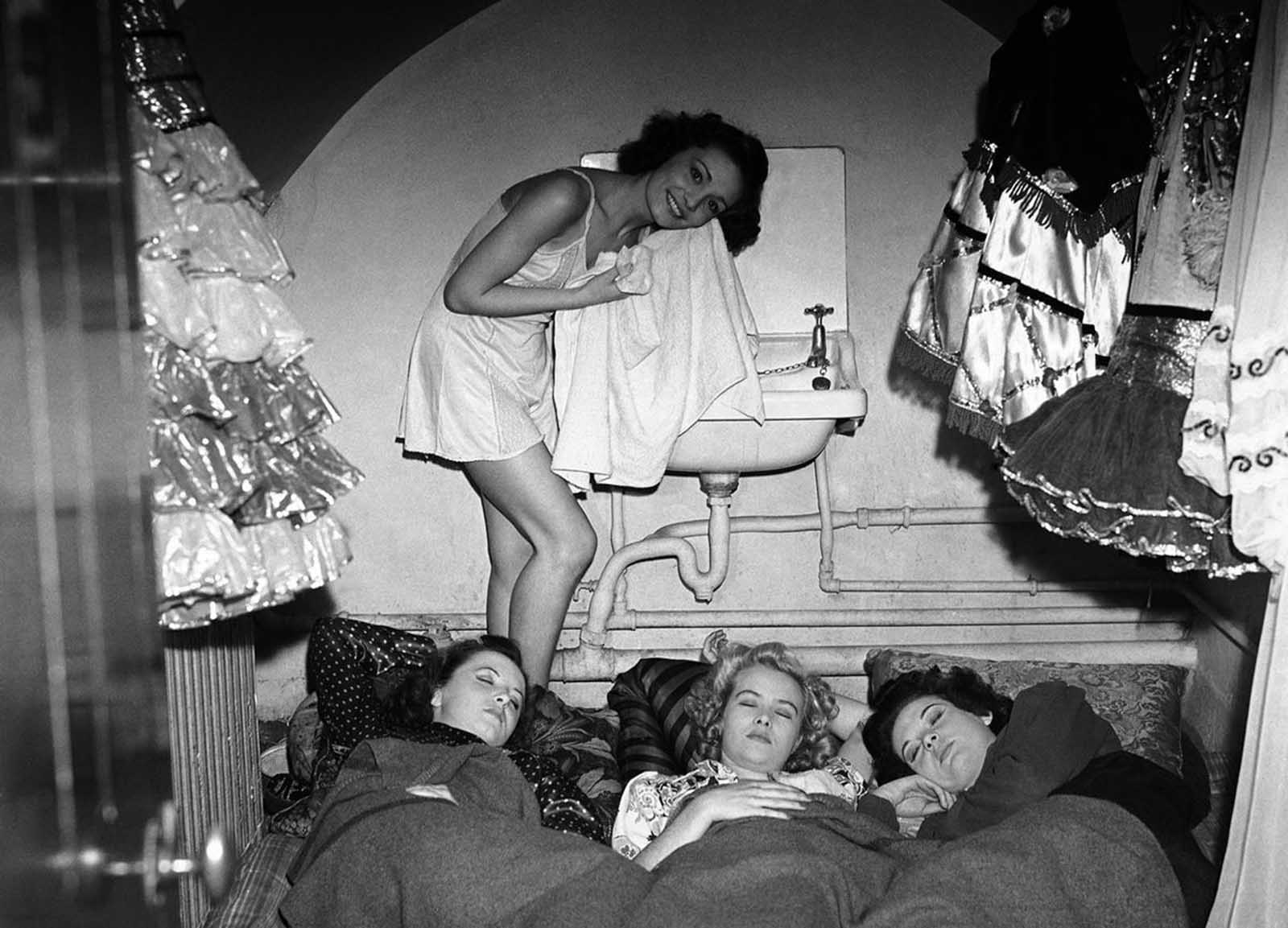

Victory for the Luftwaffe in the air battle would have exposed Great Britain to invasion by the German army, which was then in control of the ports of France only a few miles away across the English Channel. In the event, the battle was won by the Royal Air Force (RAF) Fighter Command, whose victory not only blocked the possibility of invasion but also created the conditions for Great Britain’s survival, for the extension of the war, and for the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany. On July 16, 1940, Hitler issued a directive ordering the preparation and, if necessary, the execution of a plan for the invasion of Great Britain. But an amphibious invasion of Britain would only be possible, given Britain’s large navy, if Germany could establish control of the air in the battle zone. To this end, the Luftwaffe chief, Göring, on August 2 issued the “Eagle Day” directive, laying down a plan of attack in which a few massive blows from the air were to destroy British air power and so open the way for the amphibious invasion, termed Operation “Sea Lion”. The forces engaged in the battle were relatively small. The British disposed of some 600 frontline fighters to defend the country. The Germans made available about 1,300 bombers and dive bombers, and about 900 single-engined and 300 twin-engined fighters. These were based in an arc around England from Norway to the Cherbourg Peninsula in northern coastal France. The preliminaries of the Battle of Britain occupied June and July 1940, the climax August and September, and the aftermath—the so-called Blitz—the winter of 1940–41. In the campaign, the Luftwaffe had no systematic or consistent plan of action: sometimes it tried to establish a blockade by the destruction of British shipping and ports; sometimes, to destroy Britain’s Fighter Command by combat and by the bombing of ground installations; and sometimes, to seek direct strategic results by attacks on London and other populous centers of industrial or political significance. The British, on the other hand, had prepared themselves for the kind of battle that in fact took place. Their radar early warning, the most advanced and the most operationally adapted system in the world, gave Fighter Command adequate notice of where and when to direct their fighter forces to repel German bombing raids. The Spitfire, moreover, though still in short supply, was unsurpassed as an interceptor by any fighter in any other air force. The British fought not only with the advantage—unusual for them—of superior equipment and undivided aim but also against an enemy divided in object and condemned by circumstance and by lack of forethought to fight at a tactical disadvantage. The German bombers lacked the bomb-load capacity to strike permanently devastating blows and also proved, in daylight, to be easily vulnerable to the Spitfires and Hurricanes. Britain’s radar, moreover, largely prevented them from exploiting the element of surprise. The German dive bombers were even more vulnerable to being shot down by British fighters, and long-range fighter cover was only partially available from German fighter aircraft since the latter were operating at the limit of their flying range. The German air attacks began on ports and airfields along the English Channel, where convoys were bombed and the air battle was joined. In June and July 1940, as the Germans gradually redeployed their forces, the air battle moved inland over the interior of Britain. On August 8 the intensive phase began when the Germans launched bombing raids involving up to nearly 1,500 aircraft a day and directed them against the British fighter airfields and radar stations. In four actions, on August 8, 11, 12, and 13, the Germans lost 145 aircraft as against the British loss of 88. By late August the Germans had lost more than 600 aircraft, the RAF only 260, but the RAF was losing badly needed fighters and experienced pilots at too great a rate, and its effectiveness was further hampered by bombing damage done to the radar stations. At the beginning of September, the British retaliated by unexpectedly launching a bombing raid on Berlin, which so infuriated Hitler that he ordered the Luftwaffe to shift its attacks from Fighter Command installations to London and other cities. To avoid the deadly RAF fighters, the Luftwaffe shifted almost entirely to night raids on Britain’s industrial centers. The “Blitz,” as the night raids came to be called, was to cause many deaths and great hardship for the civilian population, but it contributed little to the main purpose of the air offensive—to dominate the skies in advance of an invasion of England. On September 3 the date of invasion had been deferred to September 21, and then on September 19, Hitler ordered the shipping gathered for Operation Sea Lion to be dispersed. British fighters were simply shooting down German bombers faster than German industry could produce them. The Battle of Britain was thus won, and the invasion of England was postponed indefinitely by Hitler. The British had lost more than 900 fighters but had shot down about 1,700 German aircraft. During the following winter, the Luftwaffe maintained a bombing offensive, carrying out night-bombing attacks on Britain’s larger cities. By February 1941 the offensive had declined, but in March and April there was a revival, and nearly 10,000 sorties were flown, with heavy attacks made on London. Thereafter German strategic air operations over England withered. The Battle of Britain marked the first major defeat of Hitler’s military forces, with air superiority seen as the key to victory. Pre-war theories had led to exaggerated fears of strategic bombing, and UK public opinion was buoyed by coming through the ordeal. For the RAF, Fighter Command had achieved a great victory in successfully carrying out Sir Thomas Inskip’s 1937 air policy of preventing the Germans from knocking Britain out of the war. Churchill concluded his famous 18 June ‘Battle of Britain’ speech in the House of Commons by referring to pilots and aircrew who fought the Battle: “… if the British Empire and its Commonwealth lasts for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour’“. The British victory in the Battle of Britain was achieved at a heavy cost. Total British civilian losses from July to December 1940 were 23,002 dead and 32,138 wounded, with one of the largest single raids on 19 December 1940, in which almost 3,000 civilians died. With the culmination of the concentrated daylight raids, Britain was able to rebuild its military forces and establish itself as an Allied stronghold, later serving as a base from which the Liberation of Western Europe was launched. (Photo credit: AP Photo / Library of Congress / IWM / Britannica / Wikimedia Commons). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe