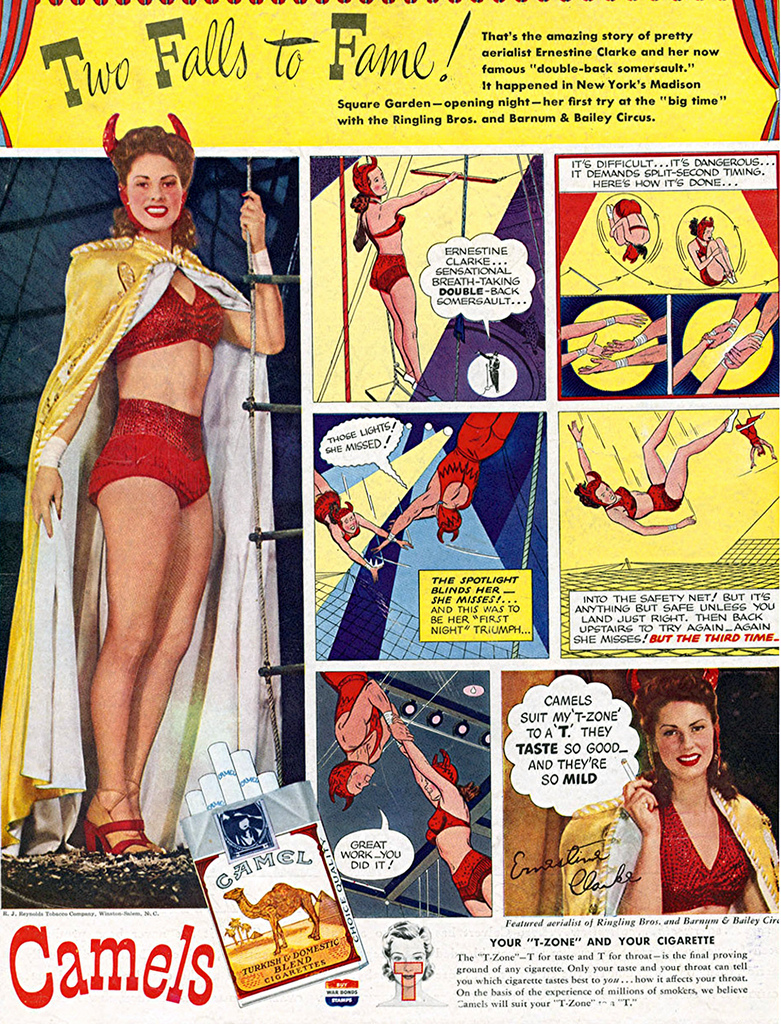

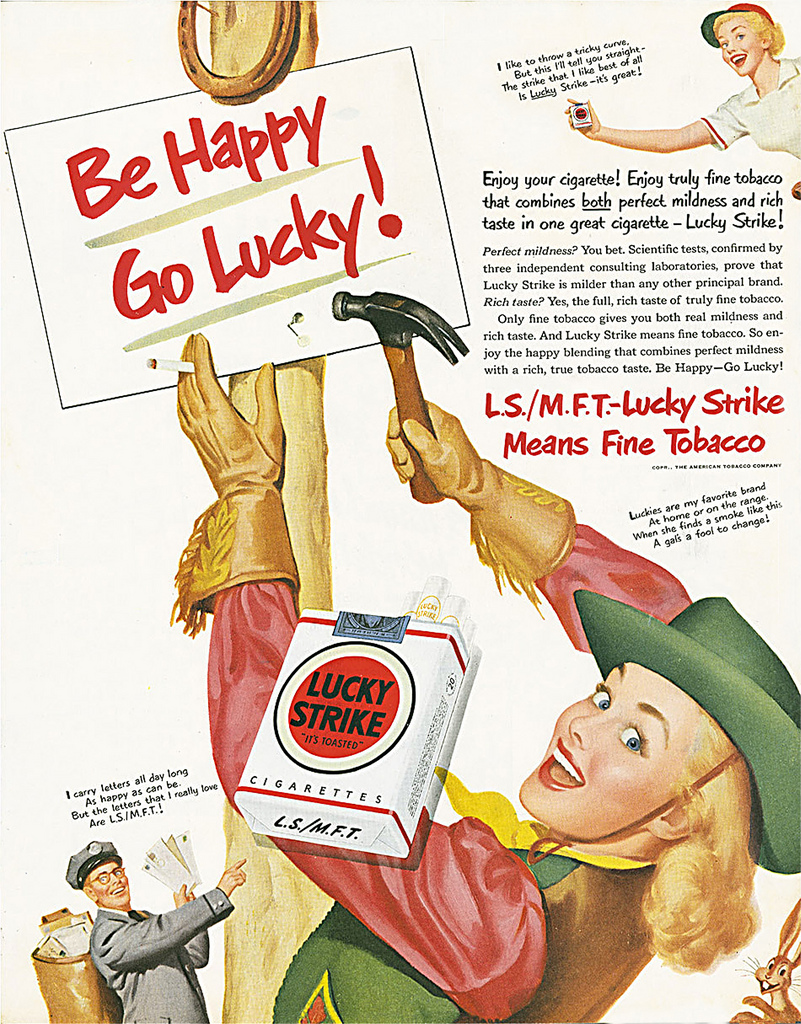

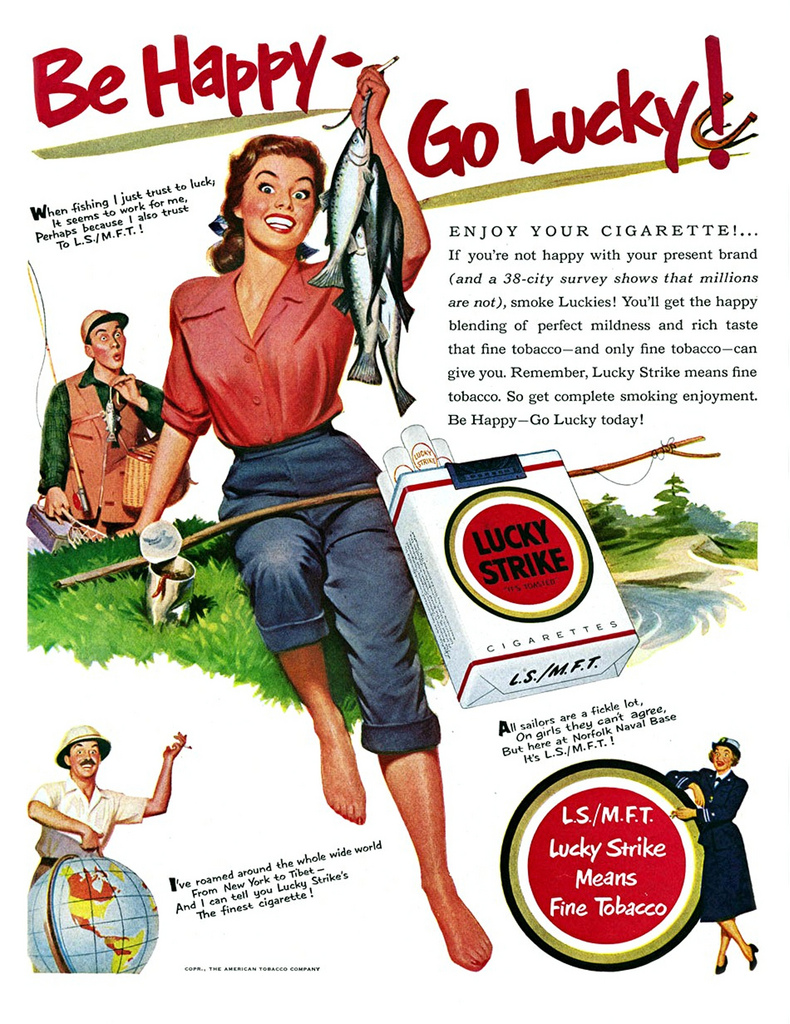

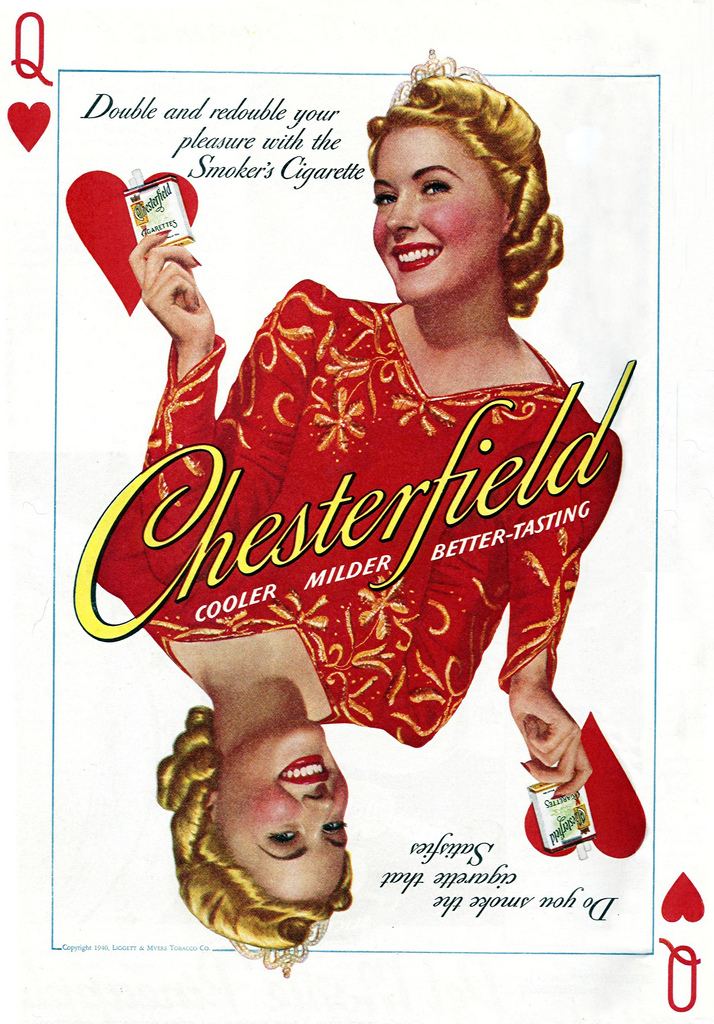

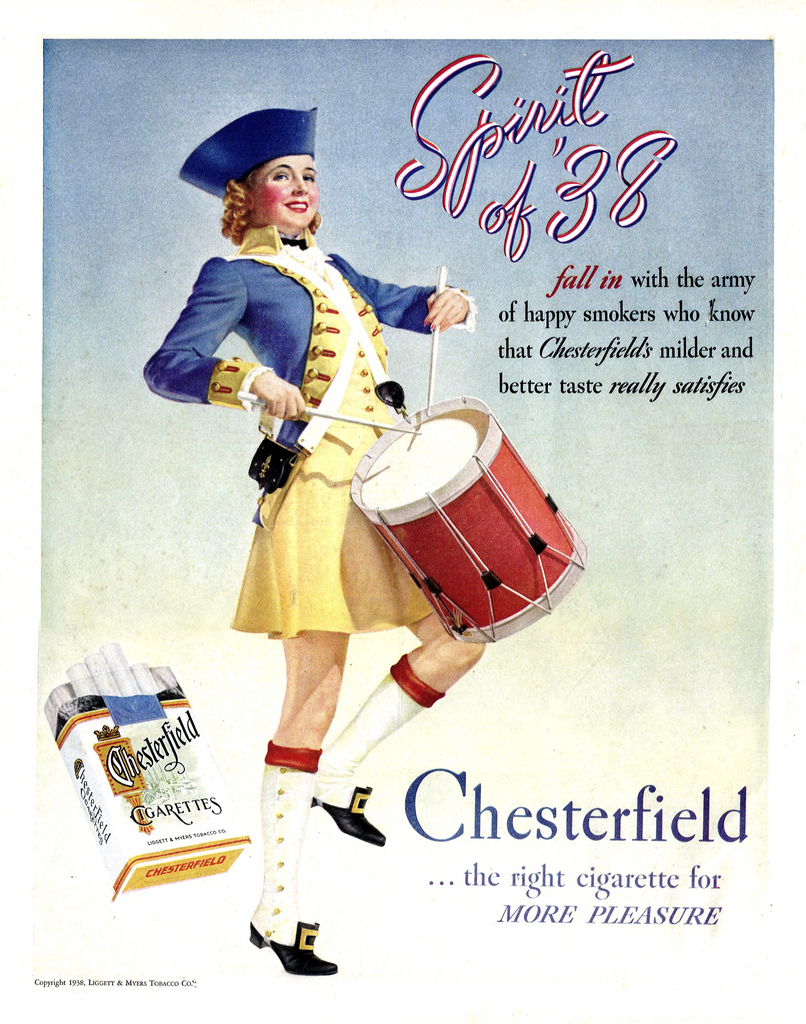

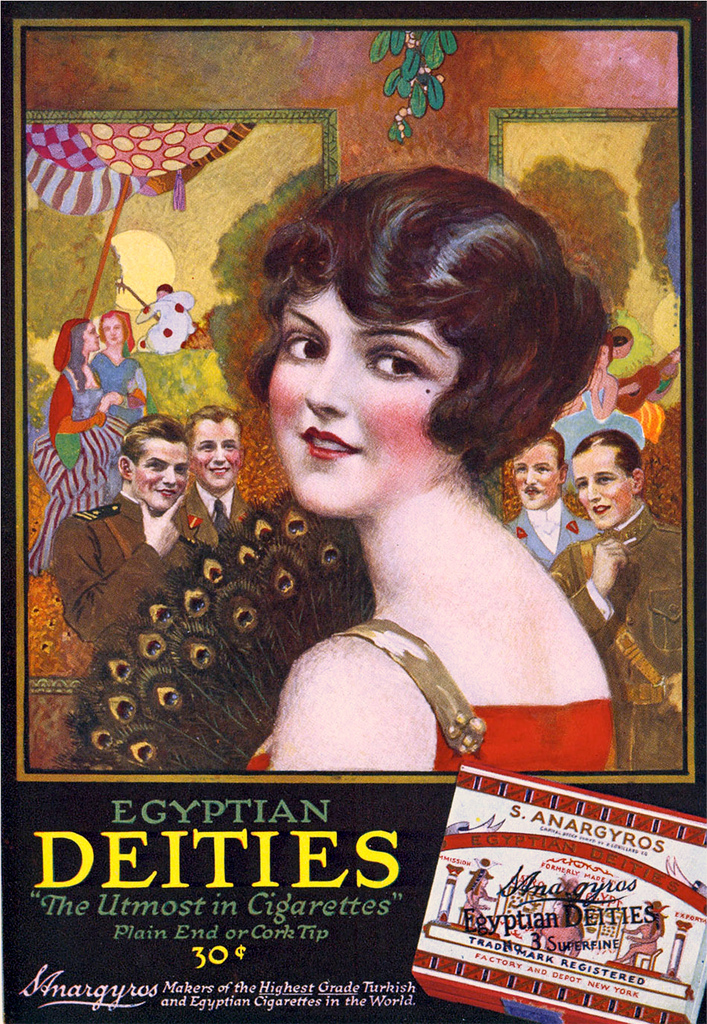

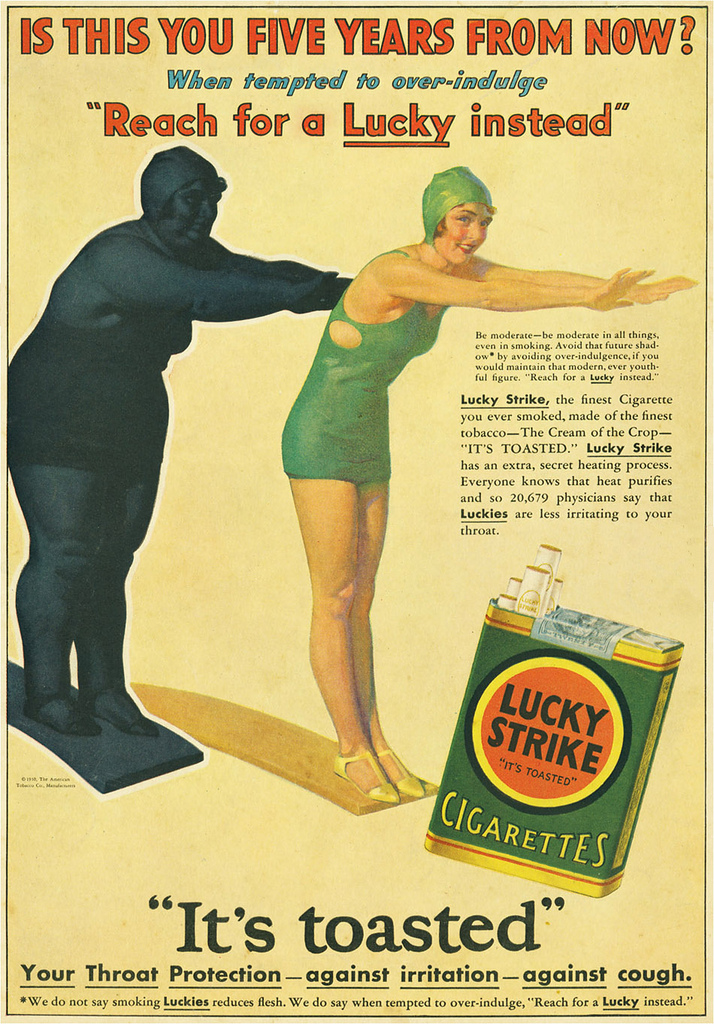

Tobacco marketers featured healthy, vigorous, fun-loving people in their ads. Often these were celebrity figures from sports and entertainment fields, other times they featured actors portraying physicians, dentists, or scientists. Some ads tapped into concerns about weight gain; some portrayed the middle-class comforts of home, holiday, recreation, or family pets. Lucky Strike led the effort to popularize smoking among women, mostly famously by the “Torches of Freedom” campaign carried out by Edward Bernays. Women were organized to smoke cigarettes during the 1929 Easter parade in New York City. In one of the adverts, they appeal to women specifically, “Ladies — the LUCKY TAG is — your fingernail protection.” The advert also included a photo and comments by Ina Clair, a stage and movie actress of the period. Other ads display the famous slogan, “It’s Toasted” which Lucky Strike had used since 1917. The reason given here for toasting is “throat protection.” The ad claims, “… the exclusive “TOASTING” Process which includes the use of modern Ultra Violet Rays — the process that expels certain harsh, biting irritants naturally present in every tobacco leaf.” On the other hand, Camel claimed, “Camels are never parched or toasted.” “We would never dream of parching or toasting these choice sun-ripened tobaccos–that would only drive off or destroy the natural moisture that makes Camels fresh in nature’s own mild way.” The ad closes with a challenge and an ominous warning, “… switch to Camels for just one day — then leave them, if you can.” The other major cigarette brand to advertise in the newspaper was Chesterfield. The selling points of Chesterfield were that they were milder, tasted better, purity (one ad claimed they were “pure as the water you drink”), and they satisfy. While it became common knowledge that tobacco consumption is bad for people’s health, back in the 1930s it was rarely acknowledged. Indeed, during the time, cigarettes were exempted from all meaningful legislation, in part because of lack of understanding of the consequences of nicotine consumption, but also due to the tobacco industry’s lobbying power. The advertisements were promoted in women’s magazines in a way that made cigarettes look stylish and desirable. Moreover, cigarette advertising gets lots of financial support due to its high success. Ultimately, women were “invited to imagine themselves as participants in the modern world and encourage to remake themselves as modern feminine subjects through their consumption practices.” There was emergence of transportation, communication, industrialization, urbanization, and modernization, which was traditionally conceived through a male lens, as women were often excluded due to their domestic roles. Advertisements for tobacco products were not generally focused on the female as a consumer but rather as an entertainer or were featured for the sake of selling the product to men. Women magazines such as Vogue, explored the culture of consumption and encouraged readers to remake themselves into modern women. The cigarette also had to be advertised and articulated in society in a certain way to remain legal and within reach. Free or subsidized branded cigarettes were distributed to troops during World War I. Demand for cigarettes in North America, which had been roughly doubling every five years, began to rise even faster, now approximately tripling during the four years of war. In the face of imminent violent death, the health harms of cigarettes became less of a concern, and there was public support for drivers to get cigarettes to the front lines. Billions of cigarettes were distributed to soldiers in Europe by national governments, the YMCA, the Salvation Army, and the Red Cross. Private individuals also donated money to send cigarettes to the front, even from jurisdictions where the sale of cigarettes was illegal. Not giving soldiers cigarettes was seen as unpatriotic. By the time the war was over, a generation had grown up, and a large proportion of adults smoked, making anti-smoking campaigns substantially more difficult. Returning soldiers continued to smoke, making smoking more socially acceptable. Temperance groups began to concentrate their efforts on alcohol. By 1927, American states had repealed all their anti-smoking laws, except those on minors.

(Photo credit: The Uncommon Wealth: Cigarette Advertising in the 1930’s – Early Years by Silver Persinger / History of the American Tobacco Company and Tobacco Advertising / Wikimedia Commons: History of nicotine marketing / Pinterest / Flickr). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)