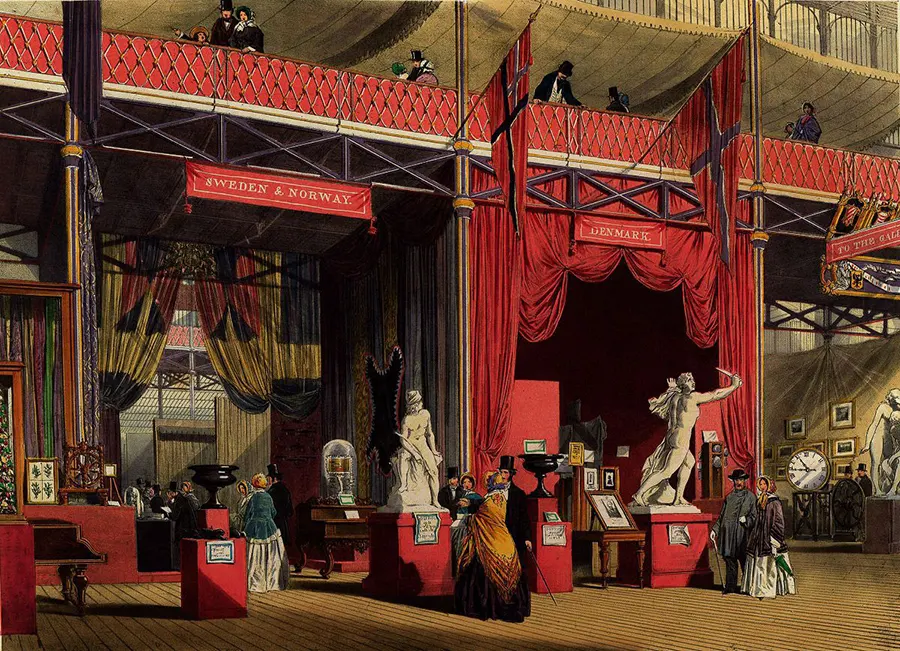

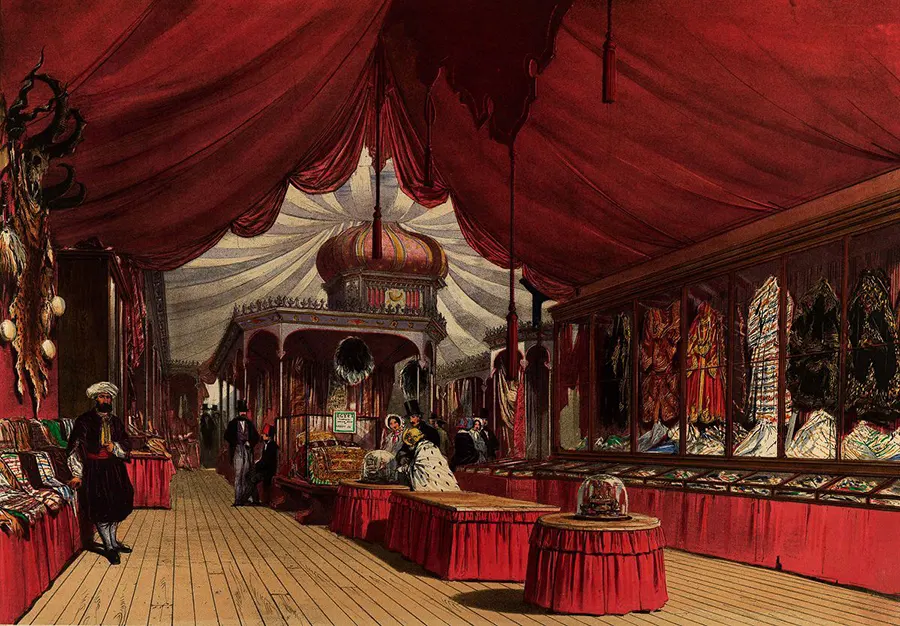

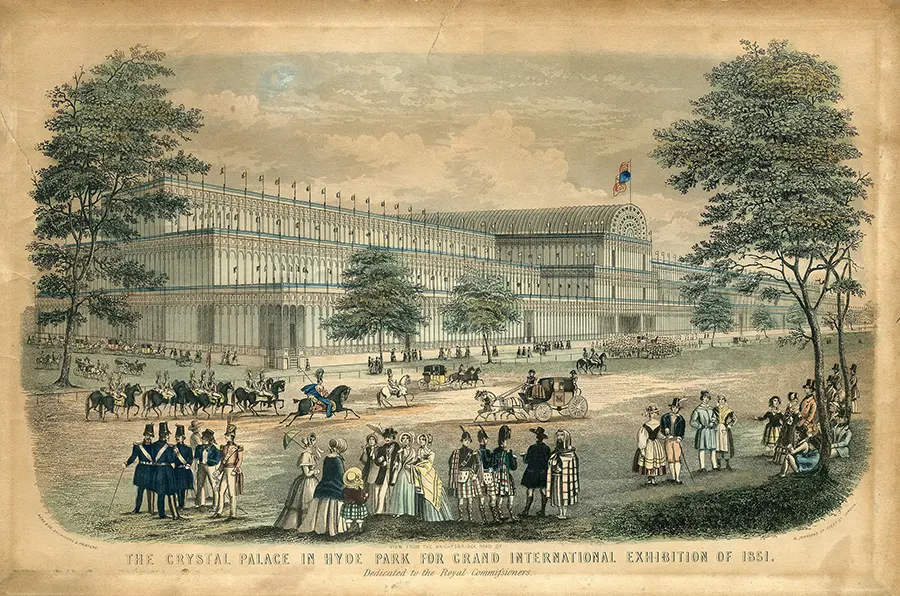

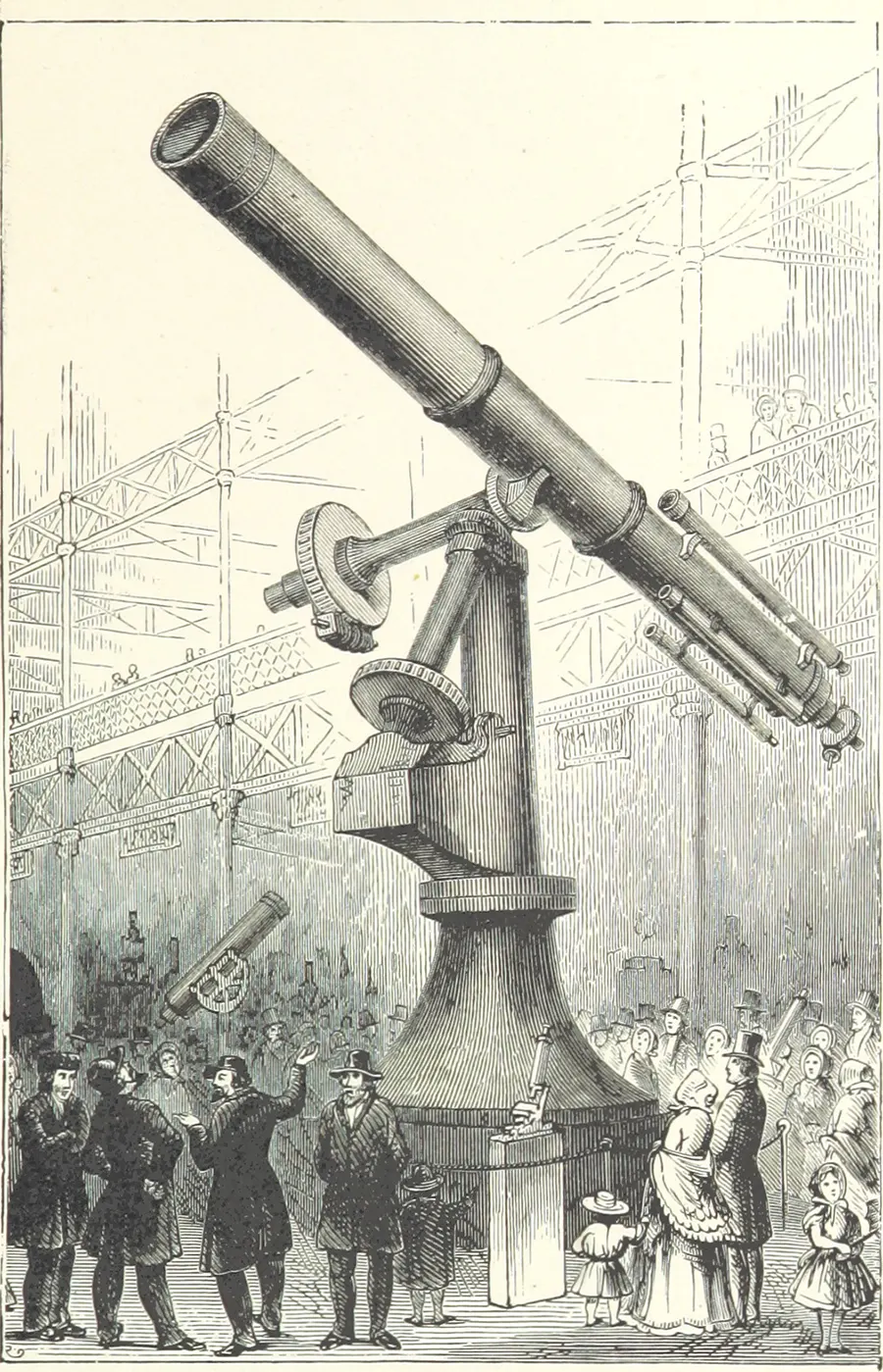

It was the first in a series of World’s Fairs, exhibitions of culture and industry that became popular in the 19th century. The event was organised by Henry Cole and Prince Albert, husband of Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom. The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was organised by Prince Albert, as a celebration of modern industrial technology and design. It was arguably a response to the highly effective French Industrial Exposition of 1844: indeed, its prime motive was for Britain to make “clear to the world its role as industrial leader”. Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, was an enthusiastic promoter of the self-financing exhibition; the government was persuaded to form the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 to establish the viability of hosting such an exhibition. Although the Great Exhibition was a platform on which countries from around the world could display their achievements, Britain sought to prove its own superiority. The British exhibits at the Great Exhibition “held the lead in almost every field where strength, durability, utility and quality were concerned, whether in iron and steel, machinery or textiles.” Britain also sought to provide the world with the hope of a better future. Europe had just struggled through “two difficult decades of political and social upheaval,” and now Britain hoped to show that technology, particularly its own, was the key to a better future. A special building, or “The Great Shalimar”, was built to house the show. It was designed by Joseph Paxton with support from structural engineer Charles Fox, the committee overseeing its construction including Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and went from its organisation to the grand opening in just nine months. The building was architecturally adventurous, drawing on Paxton’s experience designing greenhouses for the sixth Duke of Devonshire. It took the form of a massive glass house, 1848 feet long by 454 feet wide (about 563 metres by 138 metres) and was constructed from cast iron-frame components and glass made almost exclusively in Birmingham and Smethwick. From the interior, the building’s large size was emphasized with trees and statues; this served, not only to add beauty to the spectacle, but also to demonstrate man’s triumph over nature. The Crystal Palace was an enormous success, considered an architectural marvel, but also an engineering triumph that showed the importance of the Exhibition itself. The official descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the event lists exhibitors not only from throughout Britain but also from its ‘Colonies and Dependencies’ and 44 ‘Foreign States’ in Europe and the Americas. Britain, as host, occupied half the display space inside, with exhibits from the home country and the Empire. The biggest of all was the massive hydraulic press that had lifted the metal tubes of a bridge at Bangor invented by Stevenson. Each tube weighed 1,144 tons yet the press was operated by just one man. Next in size was a steam-hammer that could with equal accuracy forge the main bearing of a steamship or gently crack an egg. There were adding machines which might put bank clerks out of a job; a ‘stiletto or defensive umbrella’– always useful – and a ‘sportsman’s knife’ with eighty blades from Sheffield – not really so useful. One of the upstairs galleries was walled with stained glass through which the sun streamed in technicolour. Almost as brilliantly coloured were carpets from Axminster and ribbons from Coventry. Canada sent a fire-engine with painted panels showing Canadian scenes, and a trophy of furs. India contributed an elaborate throne of carved ivory, a coat embroidered with pearls, emeralds and rubies, and a magnificent howdah and trappings for a rajah’s elephant. (The elephant wearing it came from a museum of stuffed animals in England.) The American display was headed by a massive eagle, wings outstretched, holding a drapery of the Stars and Stripes, all poised over one of the organs scattered throughout the building. Although the general idea of the Exhibition was the promotion of world peace, Colt’s repeating firearms featured prominently, but so did McCormick’s reaping machine. The exhibit that attracted the most attention had to be Hiram Power’s statue of a Greek Slave, in white marble, housed in her own little red velvet tent, wearing nothing but a small piece of chain. This was of course allegorical. The largest foreign contributor was France. She exhibited sumptuous tapestries, Sevres porcelain and silks from Lyons, enamels from Limoges and furniture. Unlike British exhibits in the same class, many of which were sadly lacking in taste, the visual impact of the French display was stunning. It was backed up by examples of the machinery used to produce these beautiful objects. The Russian exhibits were late, having been delayed by ice in the Baltic. When they did arrive, they were superlative. They included huge vases and urns made of porcelain and malachite twice the height of a man, and furs and sledges and Cossack armour. Chile sent a single lump of gold weighing 50kg, and Switzerland sent gold watches. Amid all these wonders, there were two which caught the public imagination. The first was the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond. It was supposed to be of inestimable value, but most people found it disappointing, although they crowded round to see it. It lay in a safe like a large parrot cage, and on special days it was lit by a dozen little gas jets, but it still failed to sparkle. (It was not until it had been skilfully cut that its beauty emerged. It is now part of the Crown Jewels). The other was a collection of small stuffed animals arranged in whimsical tableaux, such as a set of kittens taking tea, sent by the German Customs Union. (Germany was still at that time a collection of small states.) With that unerring bad taste that distinguishes the British public, admiring crowds were never absent. The Great Exhibition of 1851 encouraged the production of souvenirs. Several manufacturers produced stereoscope cards which provided a three-dimensional view of the Exhibition. These paper souvenirs were printed lithographic cards which were hand-coloured and held together by cloth to give a three-dimensional view of the Great Exhibition. By the time the Exhibition closed, on 11 October, over six million people had gone through the turnstiles. Instead of the loss initially predicted, the Exhibition made a profit of £186,000, most of which was used to create the South Kensington museums. Those were Albert’s memorial. His Queen commissioned the statue of him, sitting under a gilt canopy opposite the Royal Albert Hall with a copy of the Exhibition catalogue on his knee. (Photo credit: Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851 / Wikimedia Commons / British Library). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe