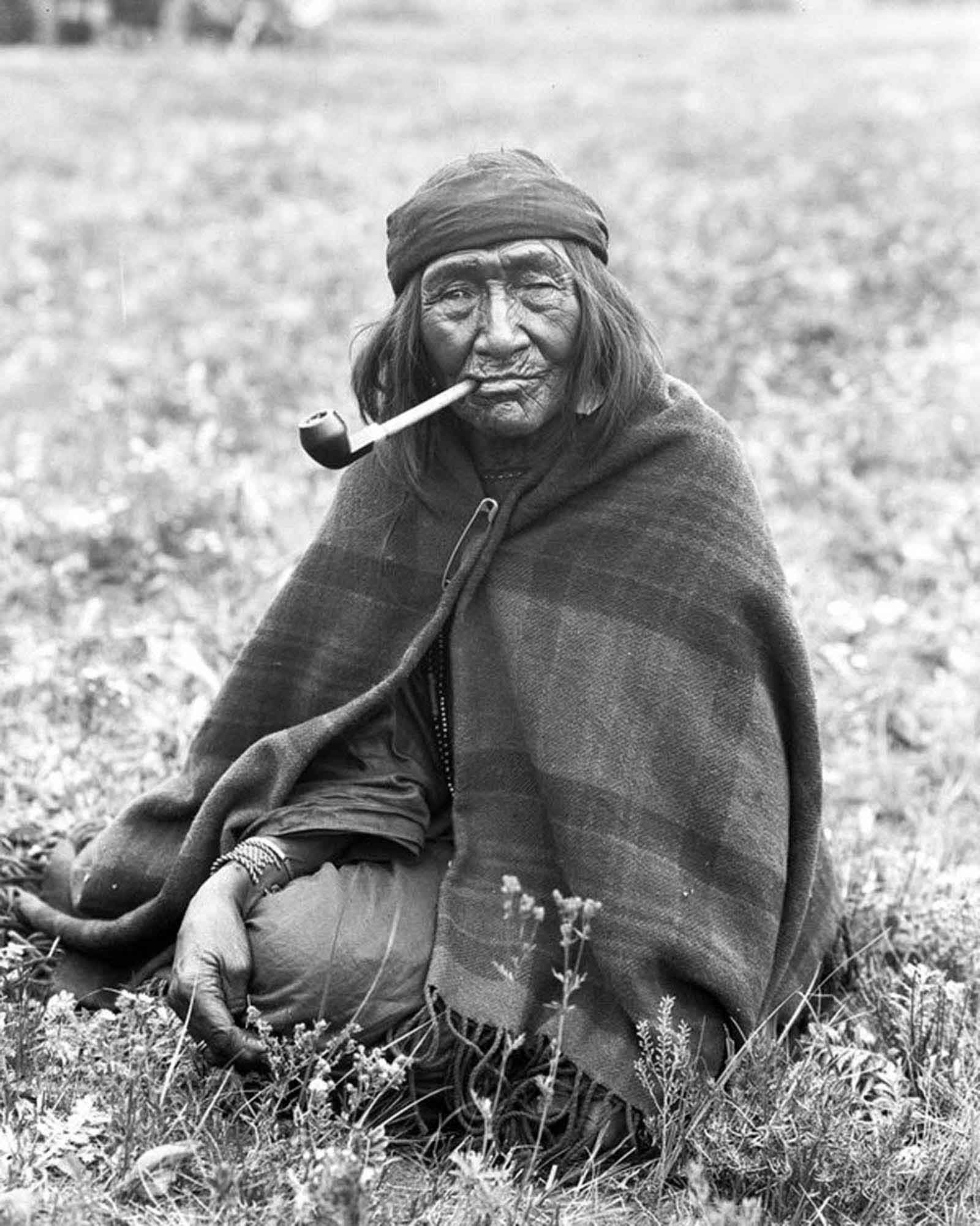

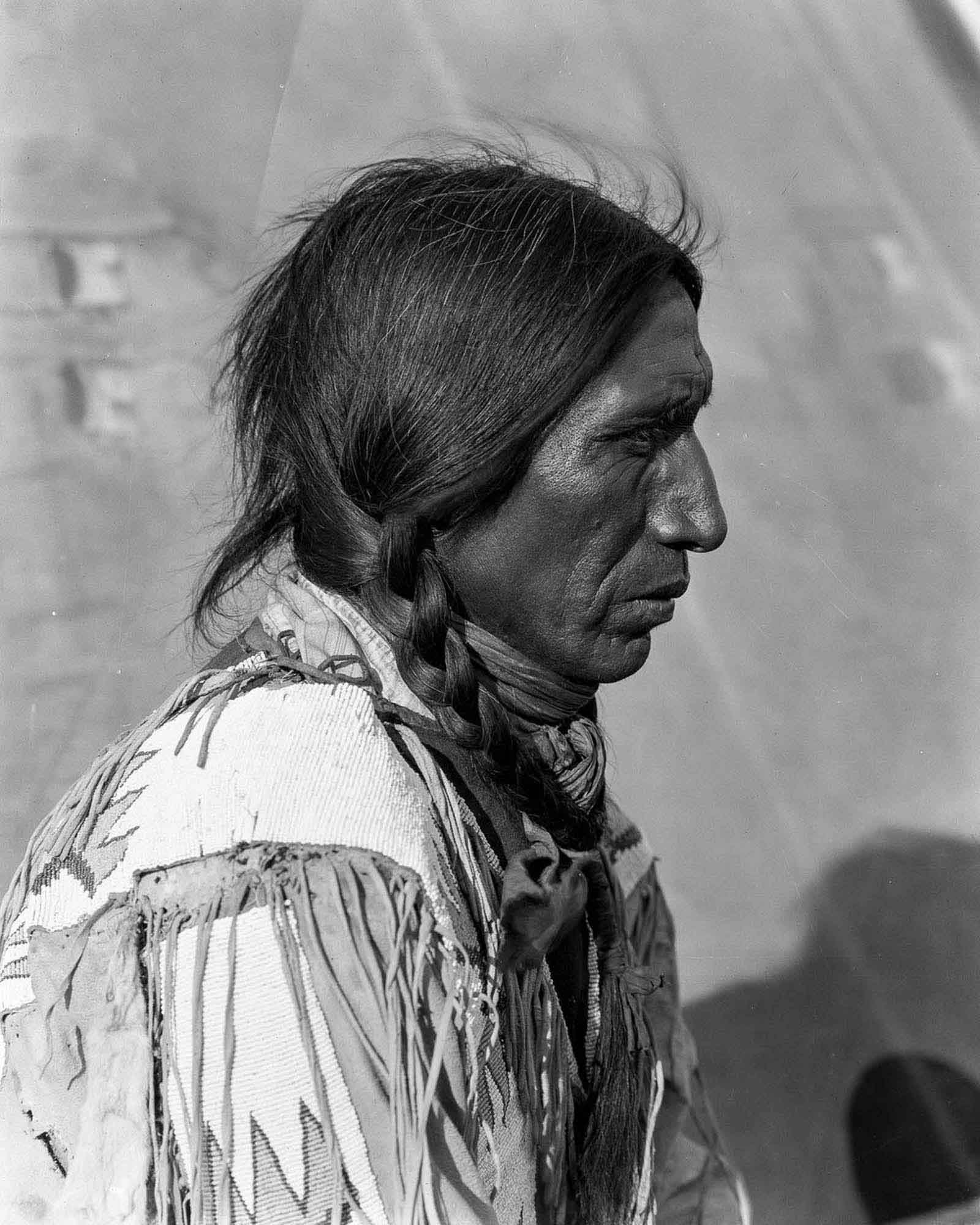

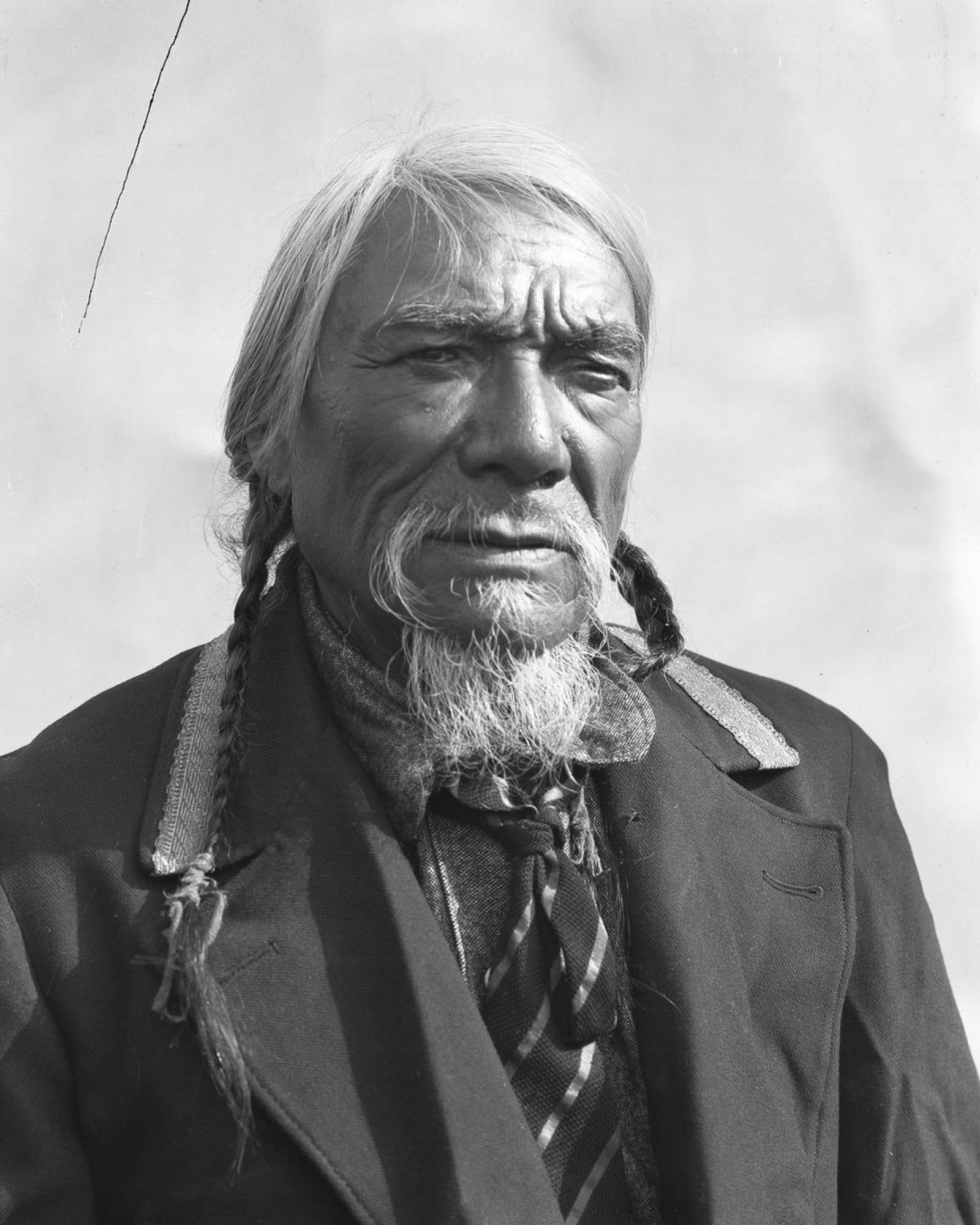

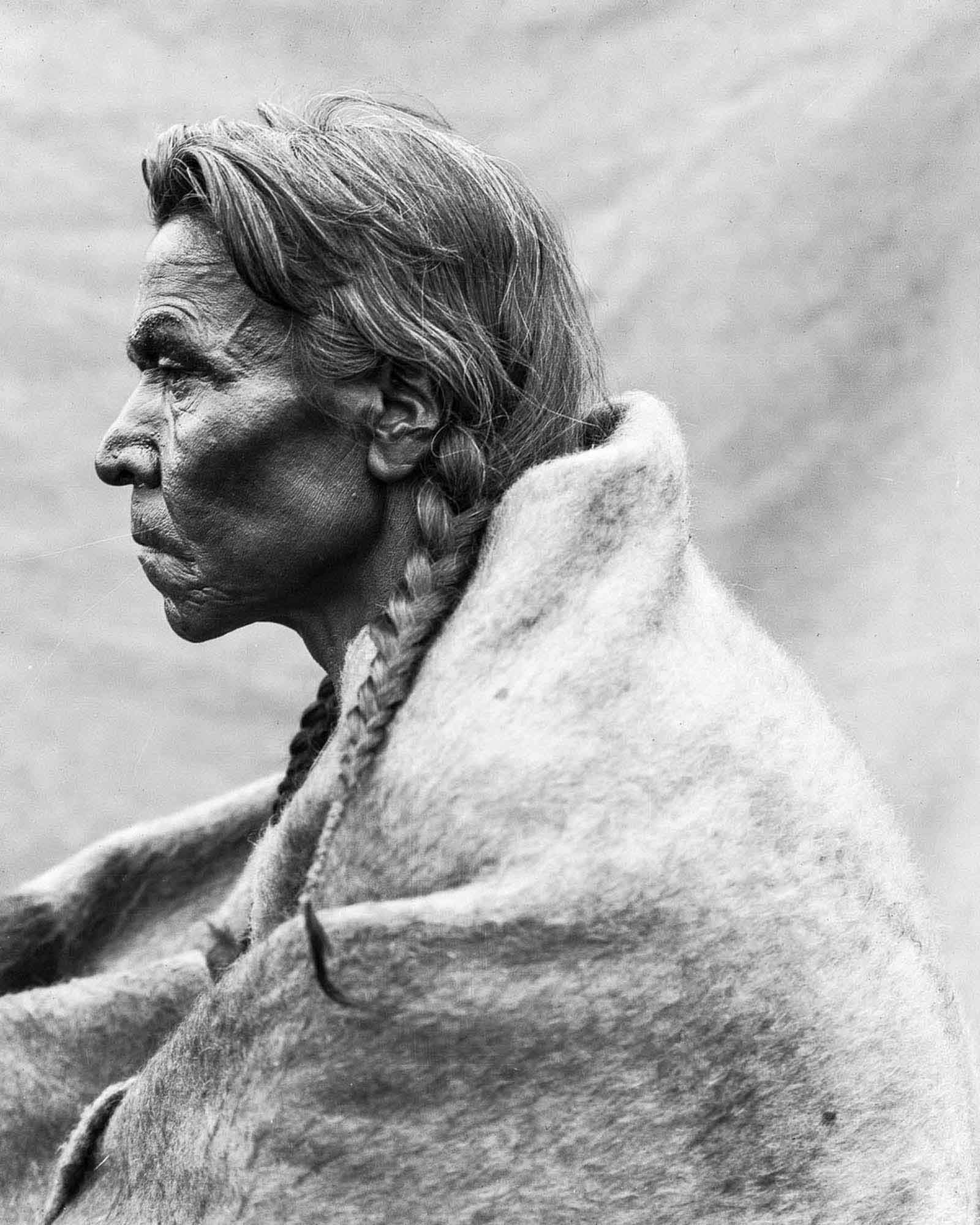

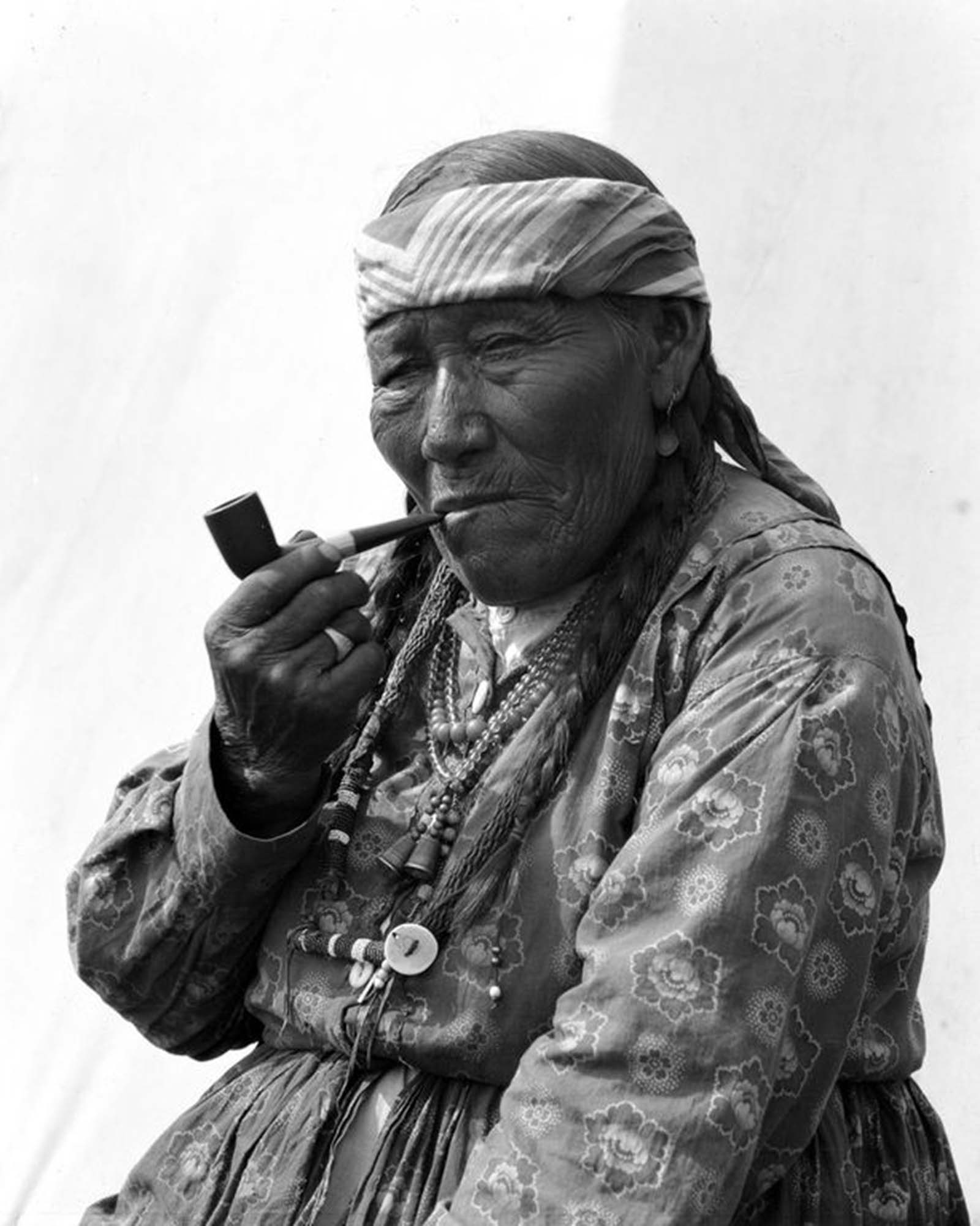

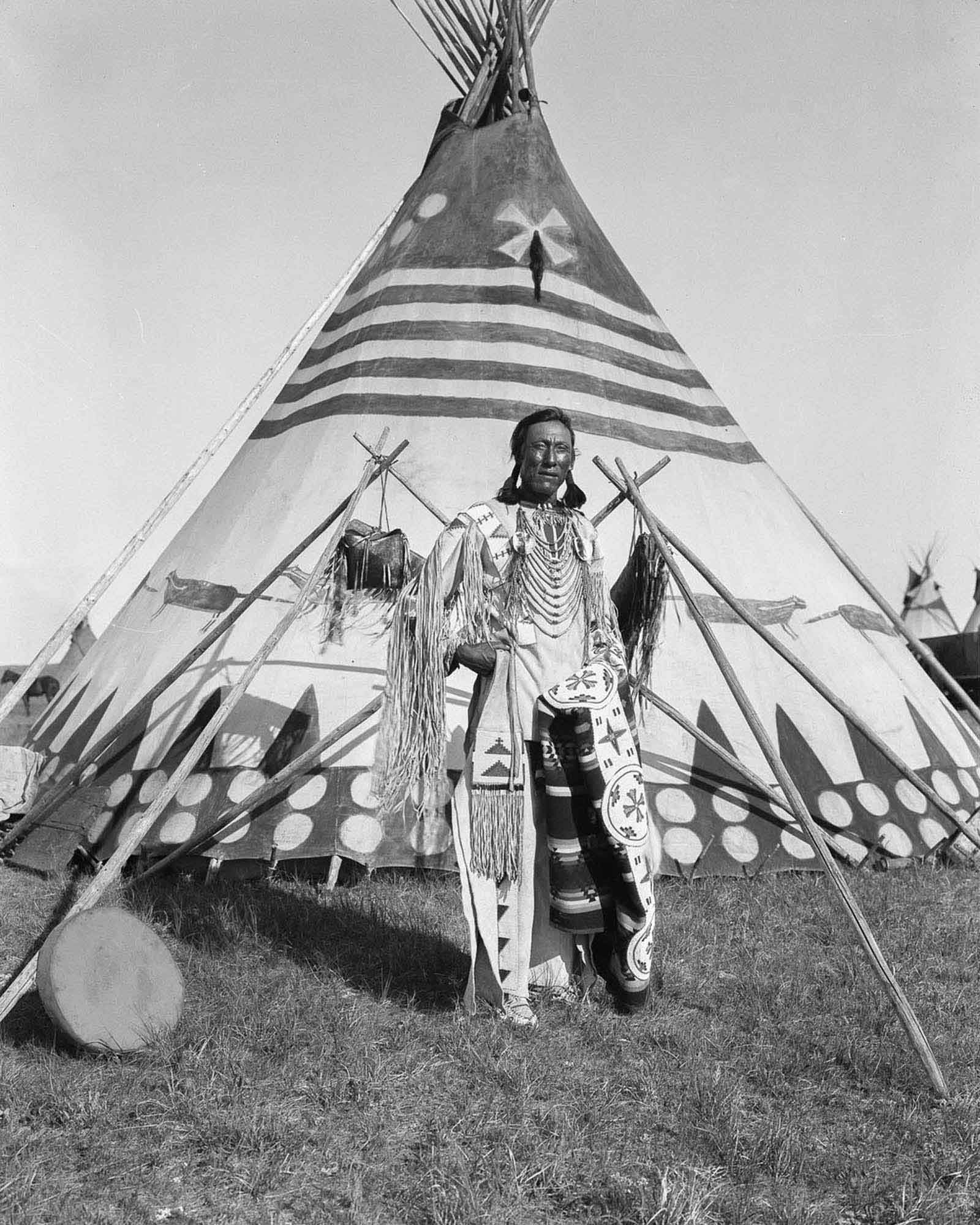

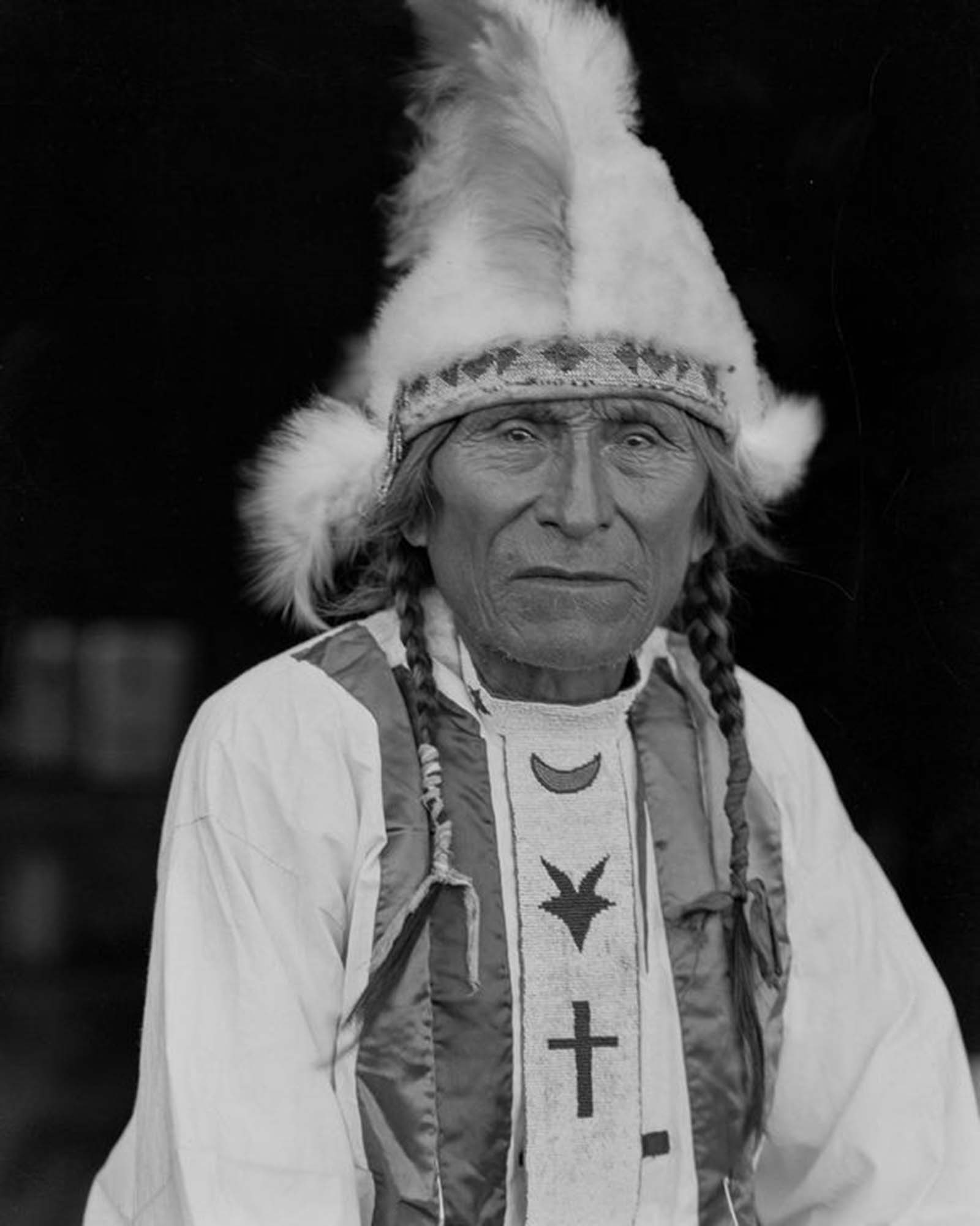

These photographs capture, among others, people from Tsuu T’ina, Siksika, Kainai, Piikani. The number of Sarcee people (Tsuu T’ina) went down to 200 in the mid-20th century but has since gone up to 2,000. They are depicted in traditional dresses, feathered headdresses, and hunting bison. These historic images, which can be found on the Provincial Archives of Alberta, include the individuals’ names and tell a story in themselves. Many of their names are themed around nature, like Lone Walking Buffalo and Running Antelope. First Nations in Alberta prior to European contact included the Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), Piikani (Peigan), and Gros Ventre (now in Montana). Other groups, including the Kootenay and the Crow, made expeditions into the land to hunt buffalo and go to war. The Tsuu T’ina, a branch of the Beaver, occupied central and northern parts of the land, while the north was occupied by the Slavey. Some speculate that men from England reached Newfoundland as early as the 1480s, predating Columbus’s voyage of 1492. The only hard evidence points to John Cabot’s English expedition of 1497 as the first known voyage to mainland North America in the new era of overseas discovery. A French explorer named Jacques Cartier arrived in 1534. He made three voyages to Canada in eight years. On his first voyage, he entered and explored the Gulf of St Lawrence. On his second, he followed St Lawrence to the Iroquoian townships of Stadacona (Québec) and Hochelaga (Montréal). The Iroquois in this area explained that the river stretched three months’ travel to the west. For the first time, Europeans had some idea of the vastness of the land. Although Cartier did not find the “great quantity of gold, and other precious things” mentioned in his instructions, he did locate the gulf’s abundant fisheries and the mainland’s furs, tempting Europe’s commercial interests. Over the next three centuries, the French, British, and other European settlers would continue to prosper from the fisheries and the fur trade in the east. Through many wars and battles that involved land and the establishment of colonies, settlers and explorers gradually started to move further west. Canada West grew rapidly because of steady immigration from England, Scotland, Ireland, and the United States. Many newcomers cleared the forests, cut lumber, and worked the rich soil. Increasing demands for land forced people to look further to the west for settlement. With the fur trade in decline, the British government and leaders in British North America became interested in the agricultural potential of the prairies. In 1867, the Dominion of Canada was created. In 1870, Canada purchased Rupert’s Land and the North West Company from the Hudson’s Bay Company, labeling the entire western and Arctic region the North-West Territories. In 1874, Canada began asserting its presence in what would become Alberta, sending the Northwest Mounted Police across the prairies to present-day Lethbridge to establish Fort Macleod. In 1875, the Mounties built forts in present-day Calgary and Edmonton. The Canadian Pacific Railway reached Calgary in 1883. The Numbered Treaties were a series of 11 treaties made from 1871 to 1921 between the Canadian government and Indigenous peoples. The government thought the treaties would help to assimilate Indigenous peoples into white, colonial society and culture. The First Nations viewed the treaties as a way to negotiate the sharing of their traditional territories. Treaty-making was so important that opening and closing ceremonies were part of the process and people traveled long distances to arrive at the negotiation locations to witness the event. In exchange for their traditional territory, government negotiators made various promises to Indigenous peoples, including special rights to lands, the distribution of cash payments, hunting and fishing tools, and farming supplies. These terms of agreement vary by treaty and are controversial and contested. Treaties still have ongoing legal and socioeconomic impacts on Indigenous communities. (Photo credit: Harry Pollard / Provincial Archives of Alberta / History of First Nation Peoples in Alberta – Alberta Regional Professional Development Consortium). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe