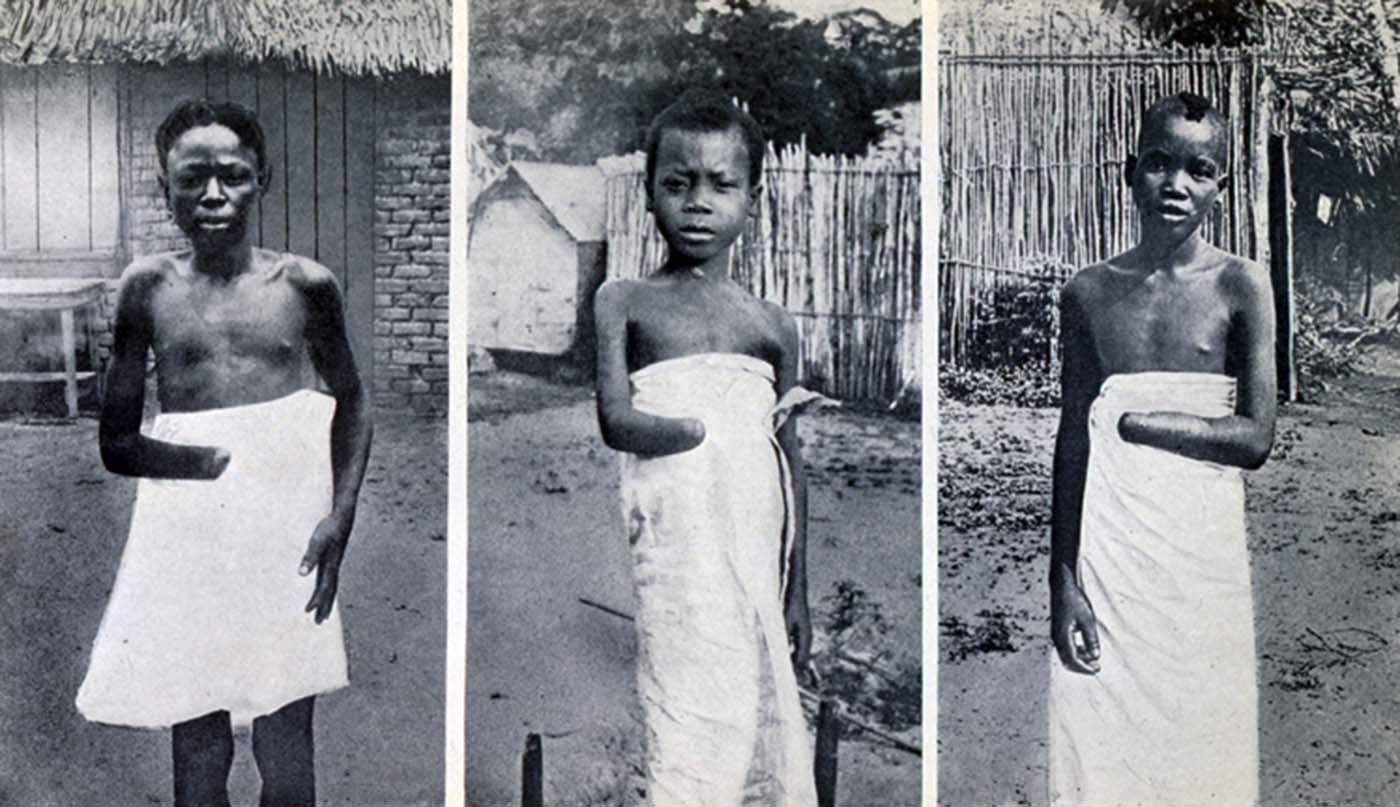

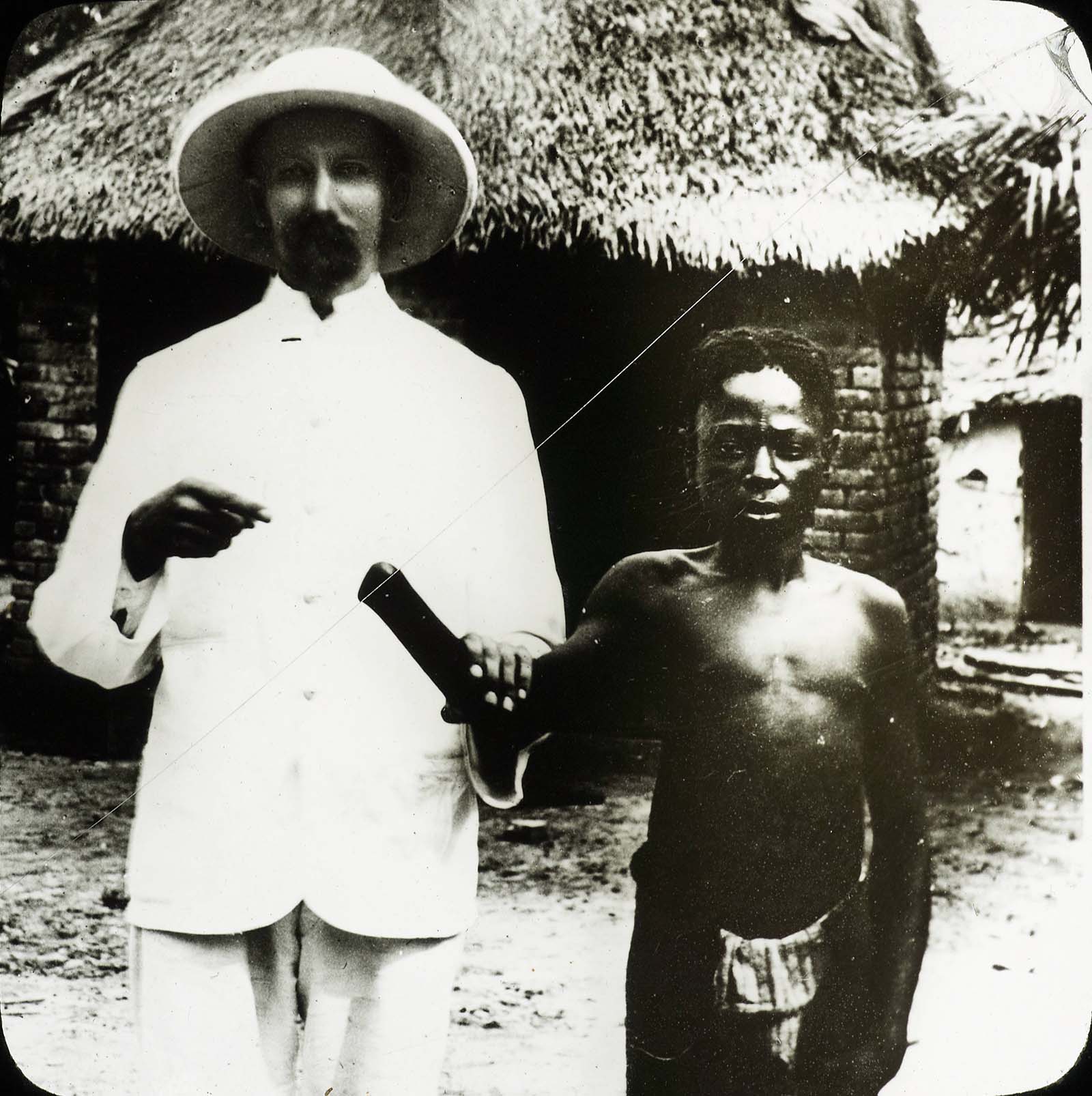

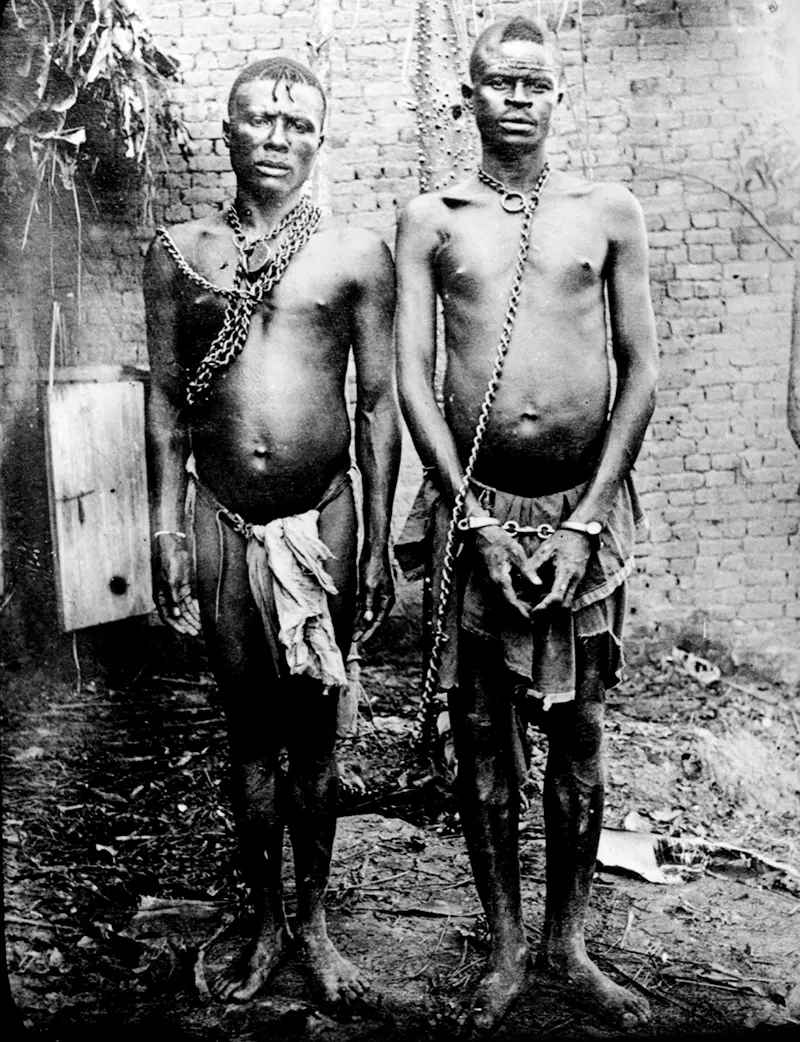

And because that didn’t seem quite cruel enough, quite strong enough to make their case, they cannibalized both Boali and her mother. And they presented Nsala with the tokens, the leftovers from the once living body of his darling child whom he so loved. His life was destroyed. They had partially destroyed it anyway by forcing his servitude but this act finished it for him. All of this filth had occurred because one man, one man who lived thousands of miles across the sea, one man who couldn’t get rich enough, had decreed that this land was his and that these people should serve his own greed. Leopold had not given any thought to the idea that these African children, these men, and women, were our fully human brothers, created equally by the same Hand that had created his own lineage of European Royalty. The Congo Free State was a corporate state in Central Africa privately owned by King Leopold II of Belgium founded and recognized by the Berlin Conference of 1885. In the 23 years (1885-1908) Leopold II ruled the Congo he massacred 10 million Africans by cutting off their hands and genitals, flogging them to death, starving them into forced labor, holding children ransom, and burning villages. The ironic part of this story is that Leopold II committed these atrocities by not even setting foot in the Congo. Under Leopold II’s administration, the Congo Free State became one of the greatest international scandals of the early 20th century. The ABIR Congo Company (founded as the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company and later known as the Compagnie du Congo Belge) was the company appointed to exploit natural rubber in the Congo Free State. ABIR enjoyed a boom through the late 1890s, by selling a kilogram of rubber in Europe for up to 10 fr which had cost them just 1.35 fr. However, this came at a cost to the human rights of those who couldn’t pay the tax with imprisonment, flogging, and other corporal punishment recorded. Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by death. Meanwhile, the Force Publique (the gendarmerie / military force) was required to provide the hand of their victims as proof when they had shot and killed someone, as it was believed that they would otherwise use the munitions (imported from Europe at considerable cost) for hunting. As a consequence, the rubber quotas were in part paid off in chopped-off hands. Sometimes the hands were collected by the soldiers of the Force Publique, sometimes by the villages themselves. There were even small wars where villages attacked neighboring villages to gather hands since their rubber quotas were too unrealistic to fill. A Catholic priest quotes a man, Tswambe, speaking of the hated state official Léon Fiévez, who ran a district along the river 500 kilometers (300 mi) north of Stanley Pool: All blacks saw this man as the devil of the Equator…From all the bodies killed in the field, you had to cut off the hands. He wanted to see the number of hands cut off by each soldier, who had to bring them in baskets…A village that refused to provide rubber would be completely swept clean. As a young man, I saw [Fiévez’s] soldier Molili, then guarding the village of Boyeka, take a net, put ten arrested natives in it, attach big stones to the net, and make it tumble into the river… Rubber causes these torments; that’s why we no longer want to hear its name spoken. Soldiers made young men kill or rape their own mothers and sisters. One junior European officer described a raid to punish a village that had protested. The European officer in command “ordered us to cut off the heads of the men and hang them on the village palisades… and to hang the women and the children on the palisade in the form of a cross”. After seeing a Congolese person killed for the first time, a Danish missionary wrote: “The soldier said ‘Don’t take this to heart so much. They kill us if we don’t bring the rubber. The Commissioner has promised us if we have plenty of hands he will shorten our service”. In Forbath’s words: The baskets of severed hands, set down at the feet of the European post commanders, became the symbol of the Congo Free State… The collection of hands became an end in itself. Force Publique soldiers brought them to the stations in place of rubber; they even went out to harvest them instead of rubber… They became a sort of currency. They came to be used to make up for shortfalls in rubber quotas, to replace… the people who were demanded for the forced labor gangs; and the Force Publique soldiers were paid their bonuses on the basis of how many hands they collected.

In theory, each right hand proved a killing. In practice, soldiers sometimes “cheated” by simply cutting off the hand and leaving the victim to live or die. More than a few survivors later said that they had lived through a massacre by acting dead, not moving even when their hands were severed, and waiting till the soldiers left before seeking help. In some instances, a soldier could shorten his service term by bringing more hands than the other soldiers, which led to widespread mutilations and dismemberment. A reduction of the population of the Congo is noted by all who have compared the country at the beginning of Leopold’s control with the beginning of Belgian state rule in 1908, but estimates of the death toll vary considerably. Estimates of contemporary observers suggest that the population decreased by half during this period and these are supported by some modern scholars such as Jan Vansina. Others dispute this. Scholars at the Royal Museum for Central Africa argue that a decrease of 15 percent over the first forty years of colonial rule (up to the census of 1924).

The legacy of the population decline of Leopold’s reign left the subsequent colonial government with a severe labor shortage and it often had to resort to mass migrations to provide workers to emerging businesses. The atrocities of the era generated public debate about Leopold, his specific role in them, and his legacy. Belgian crowds booed at his funeral in 1909 to express their dissatisfaction with his rule of the Congo. Attention to the atrocities subsided in the following years and statues of him were erected in the 1930s at the initiative of Albert I, while the Belgian government celebrated his accomplishments in Belgium. The release of Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost in 1999 briefly reignited debate in Belgium, which resurfaced periodically over the following 20 years. In 2005, a motion before the British House of Commons, introduced by Andrew Dismore, called for the recognition of the Congo Free State’s atrocities as a “colonial genocide” and called on the Belgian government to issue a formal apology. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Google Books). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe