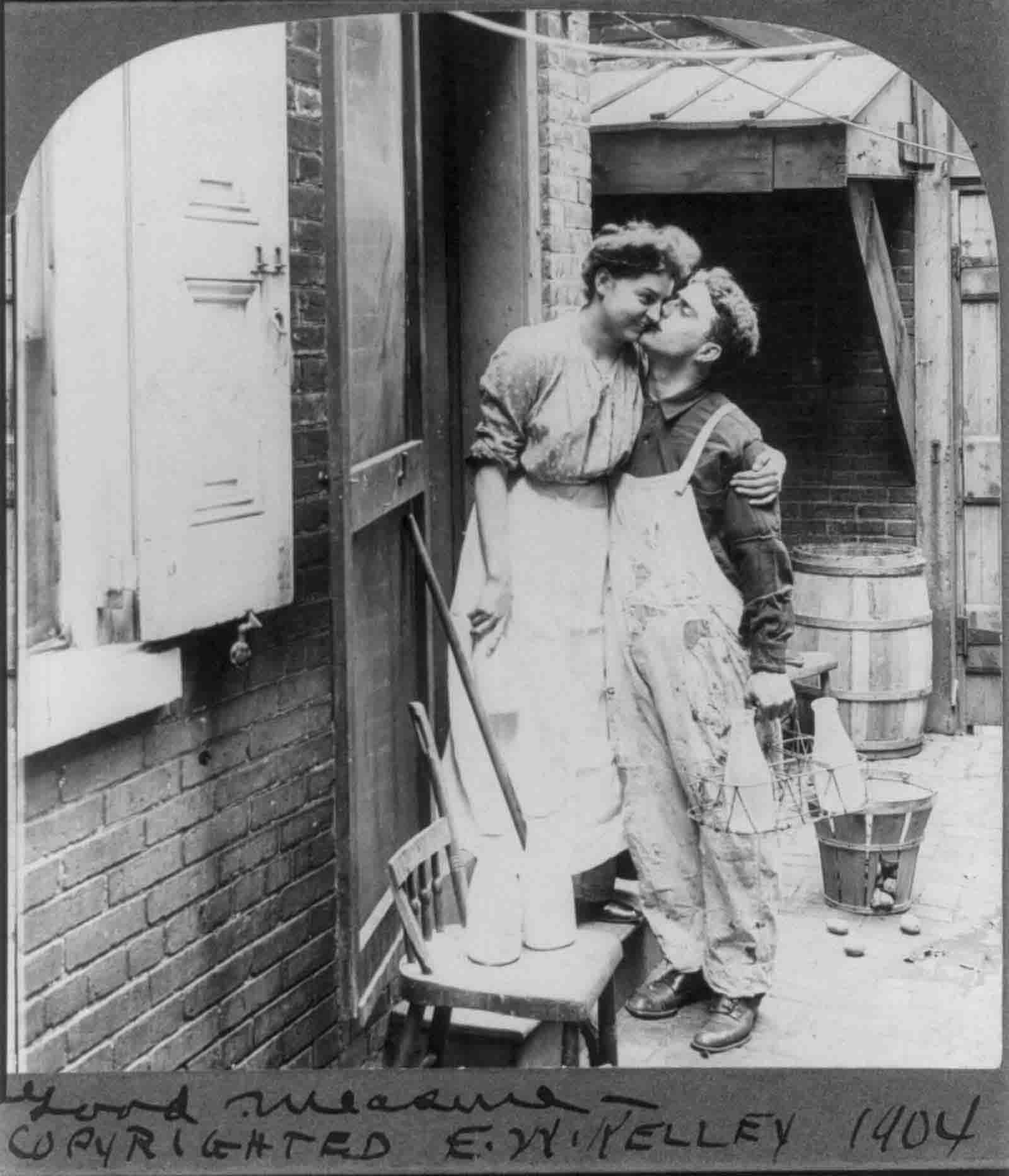

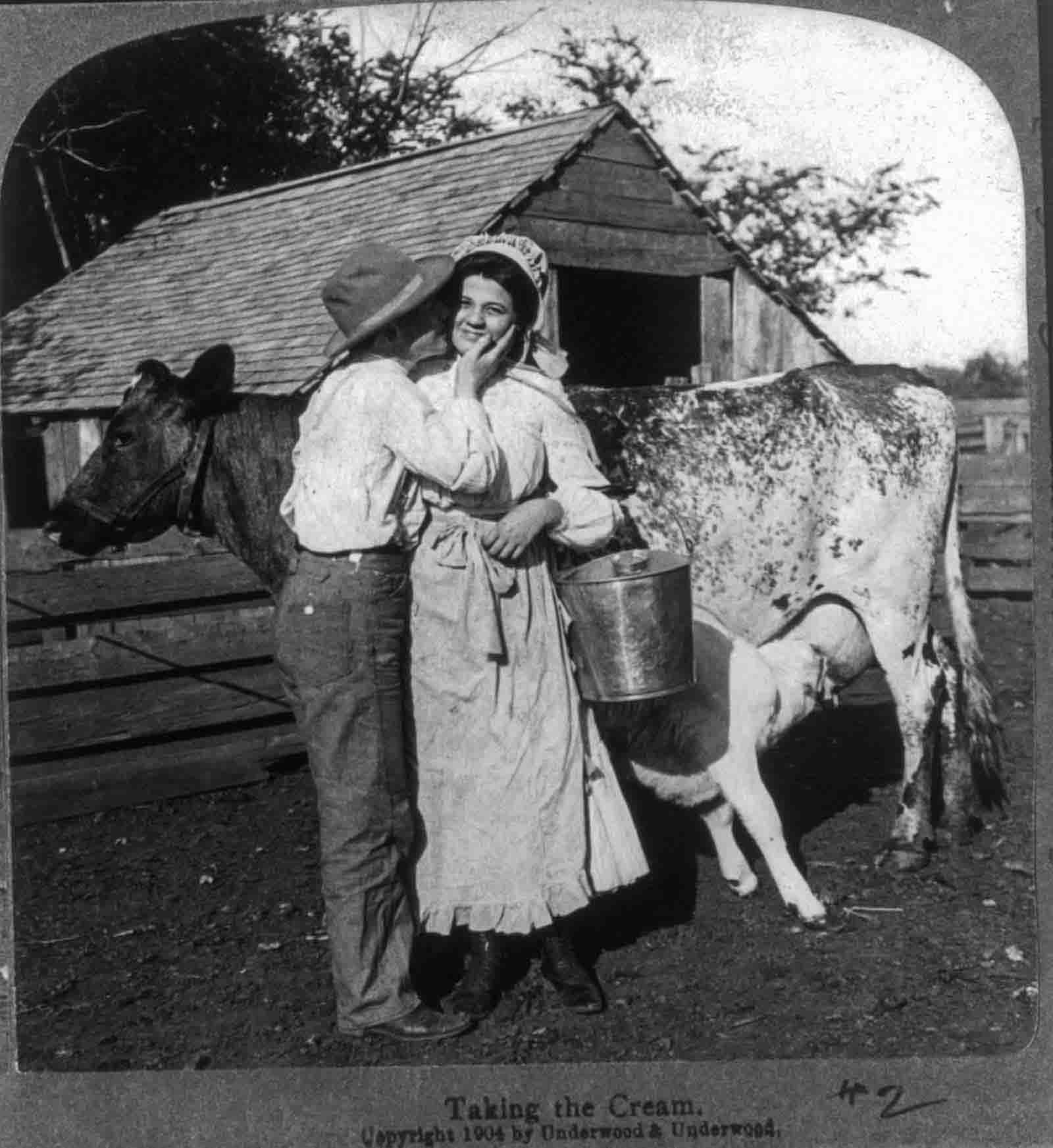

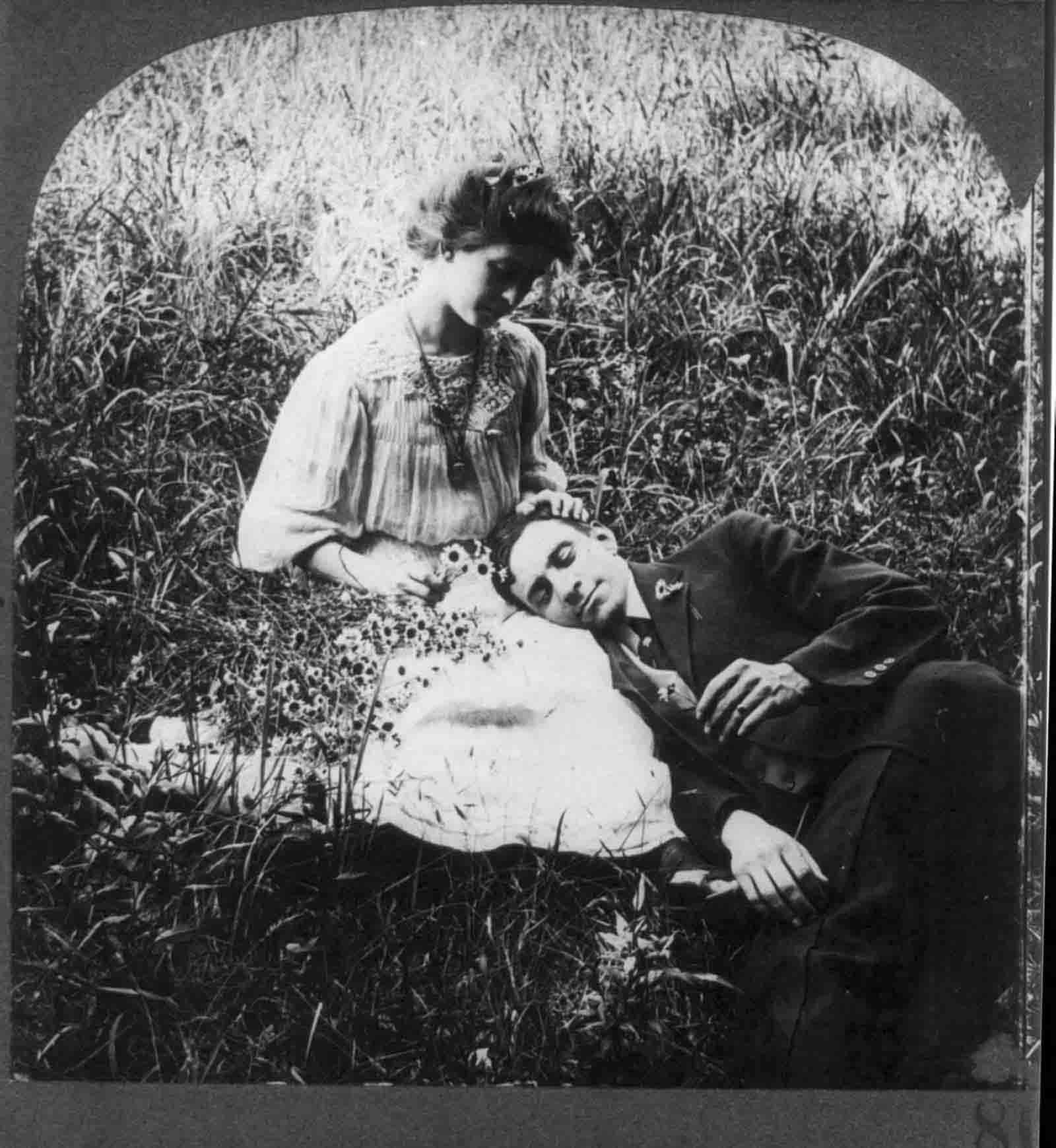

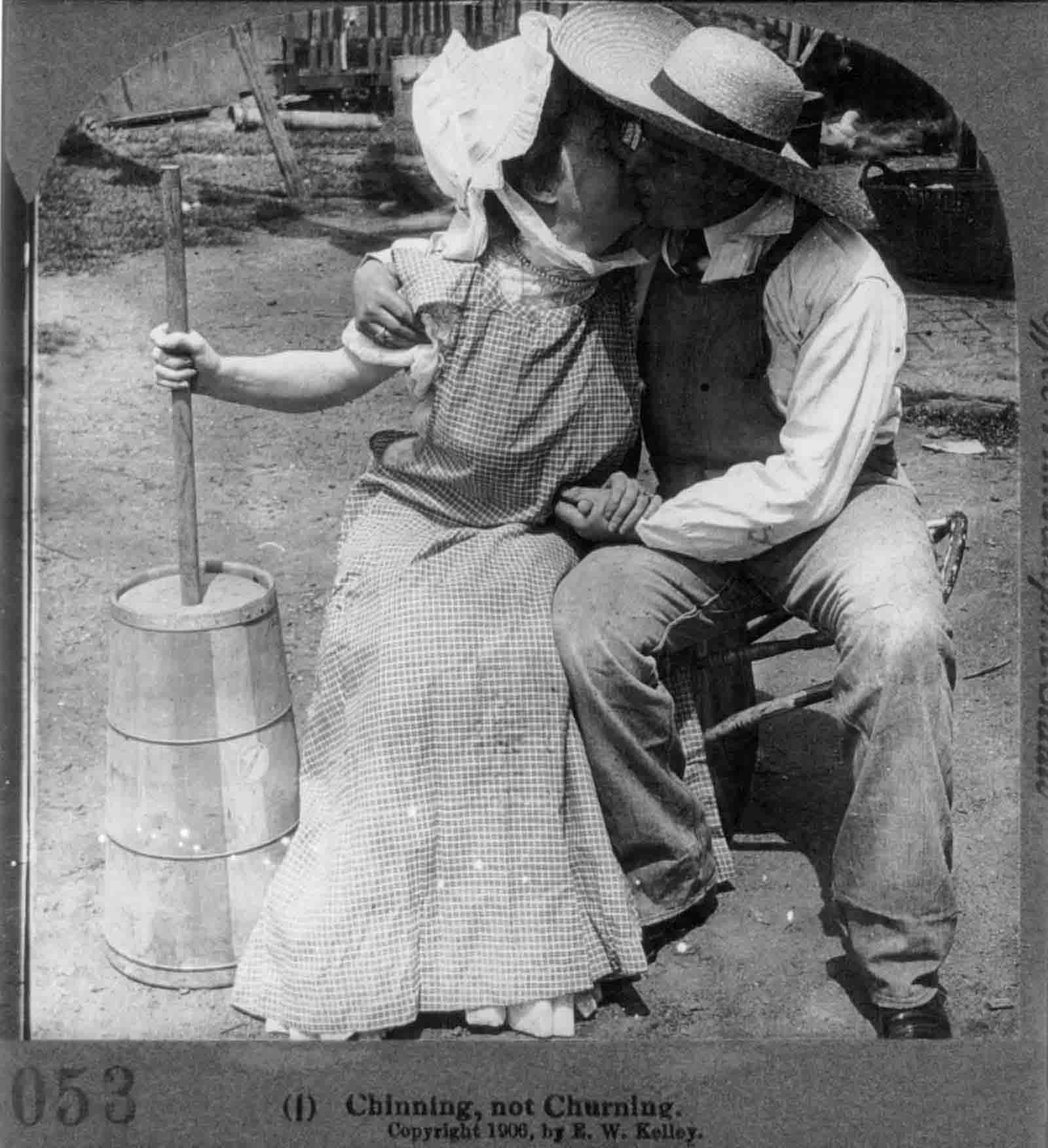

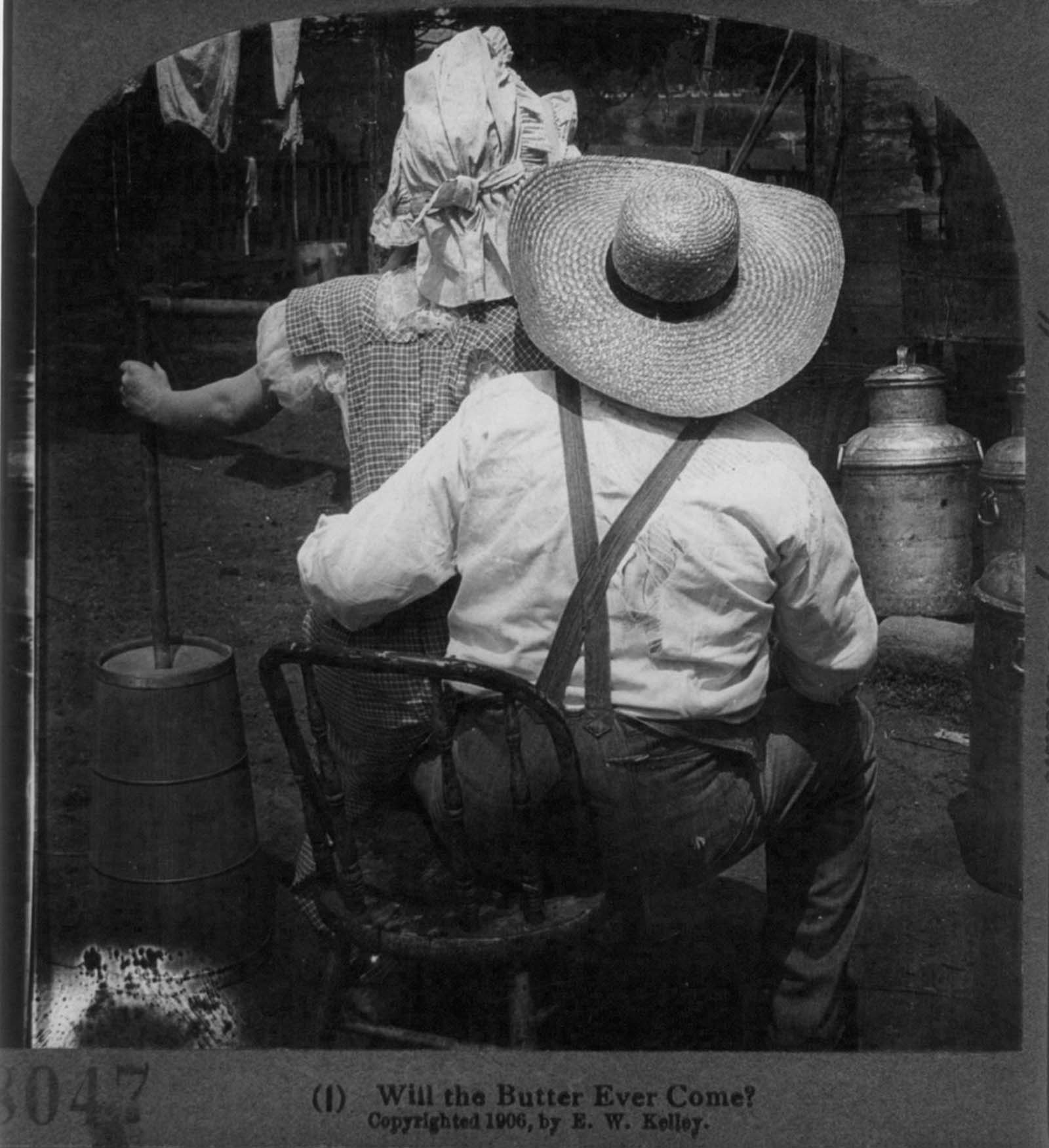

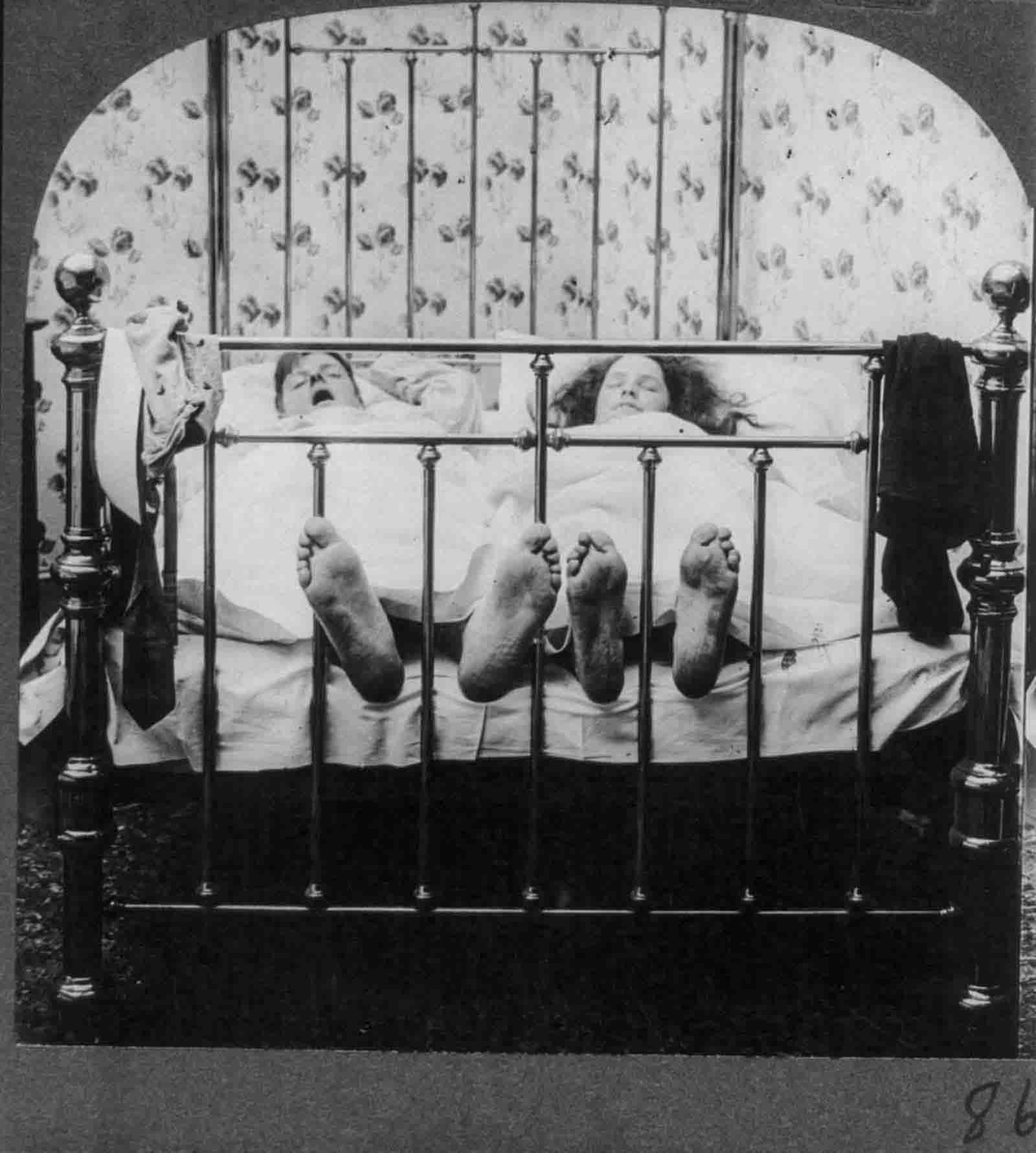

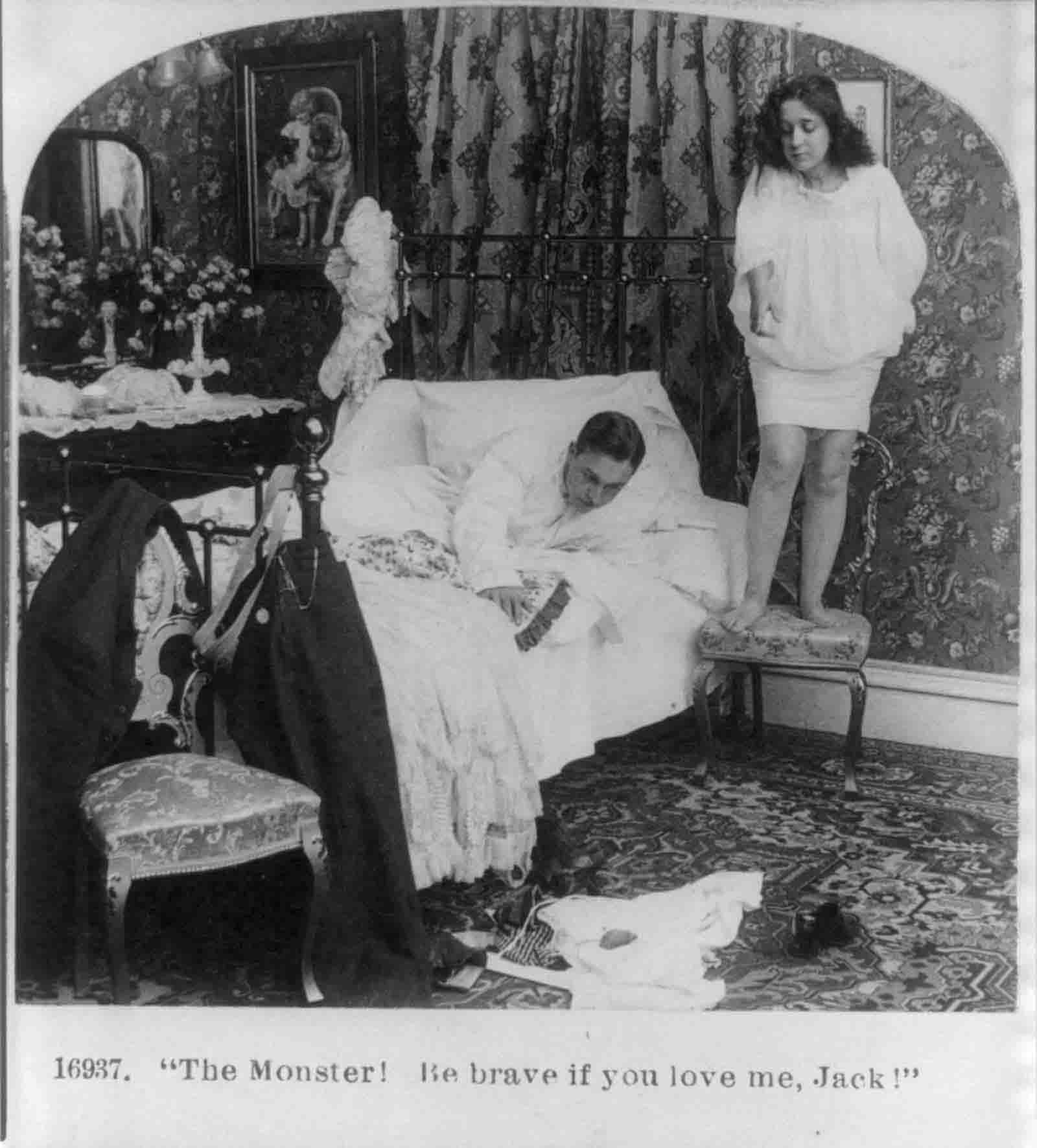

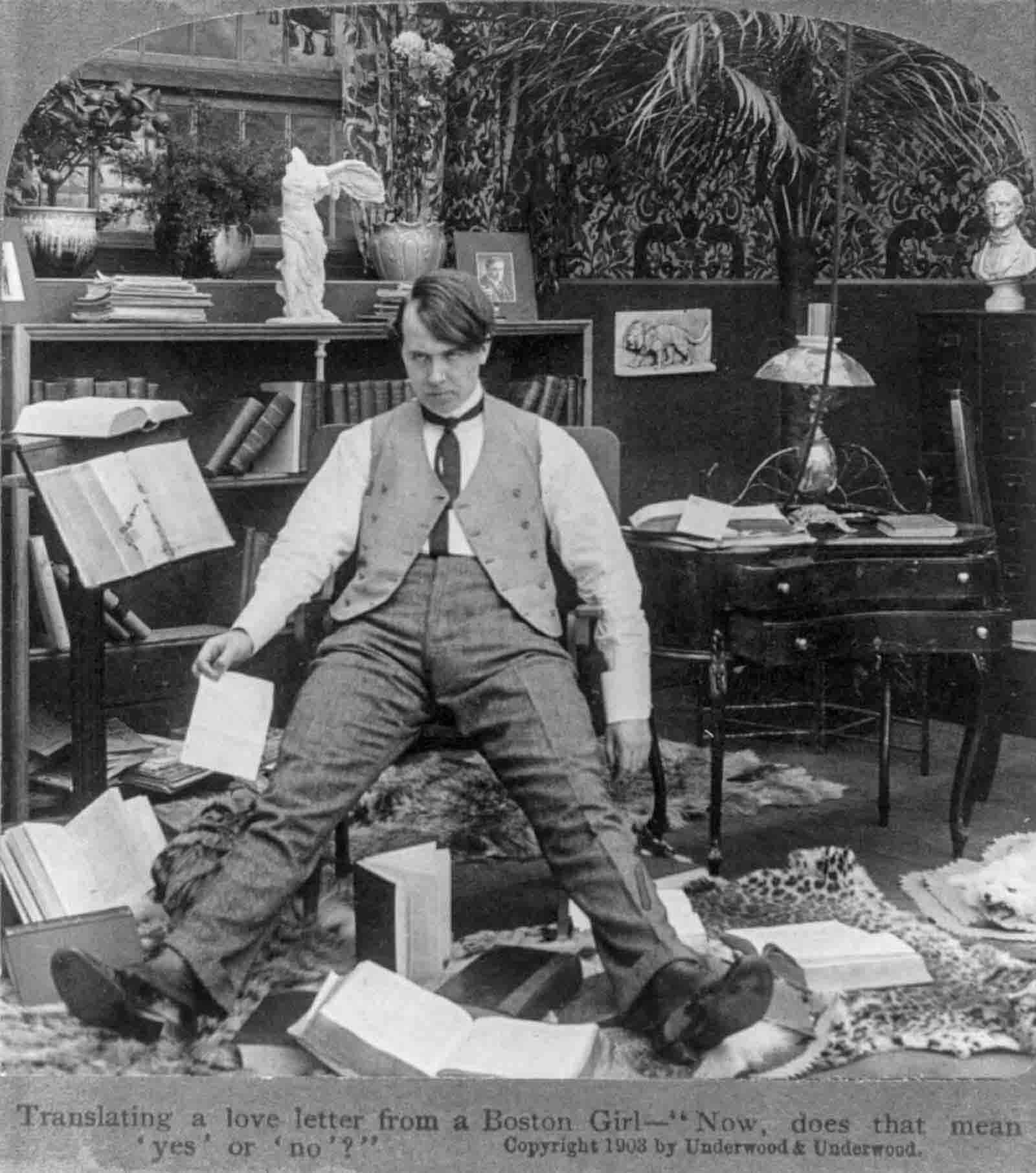

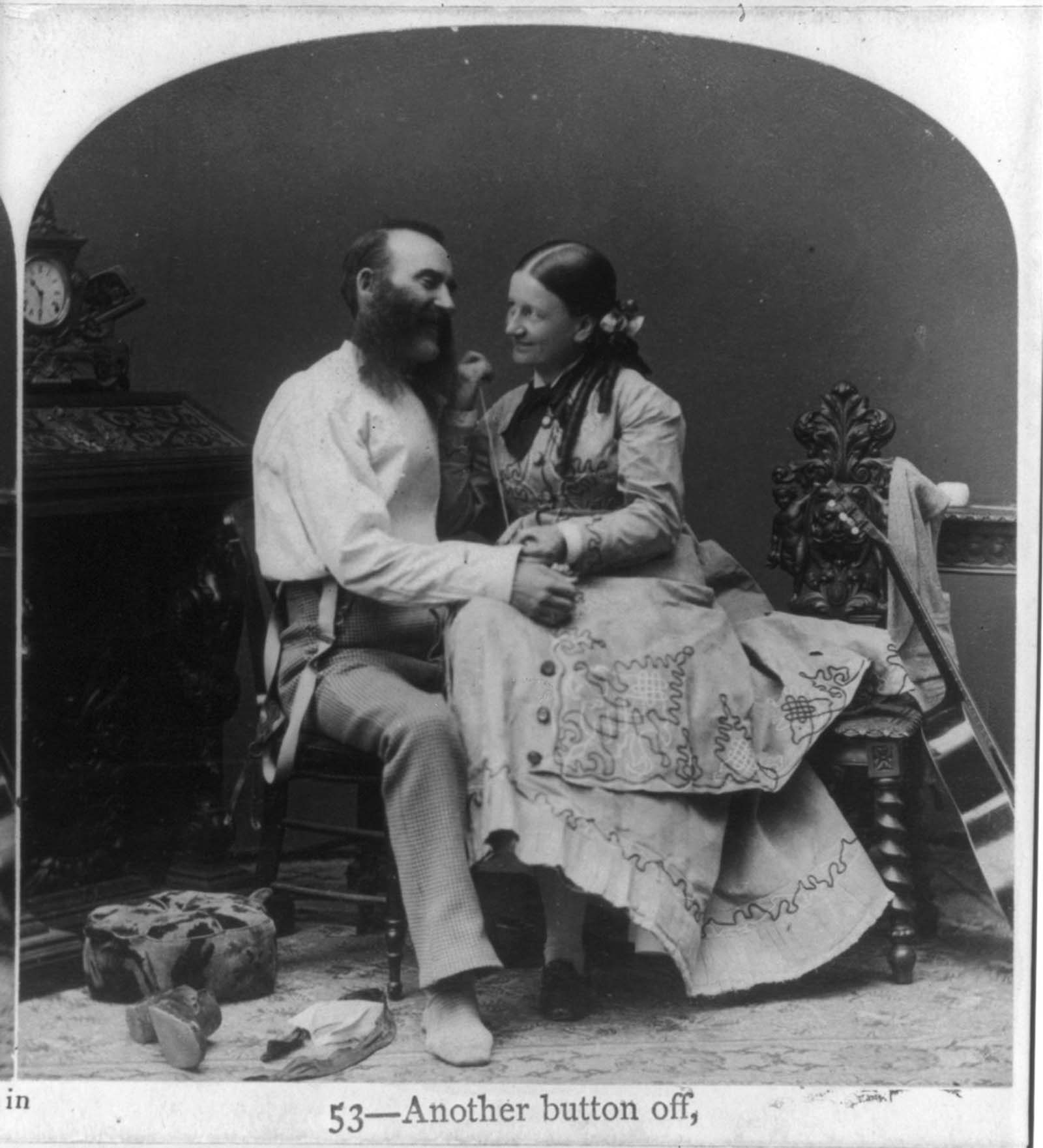

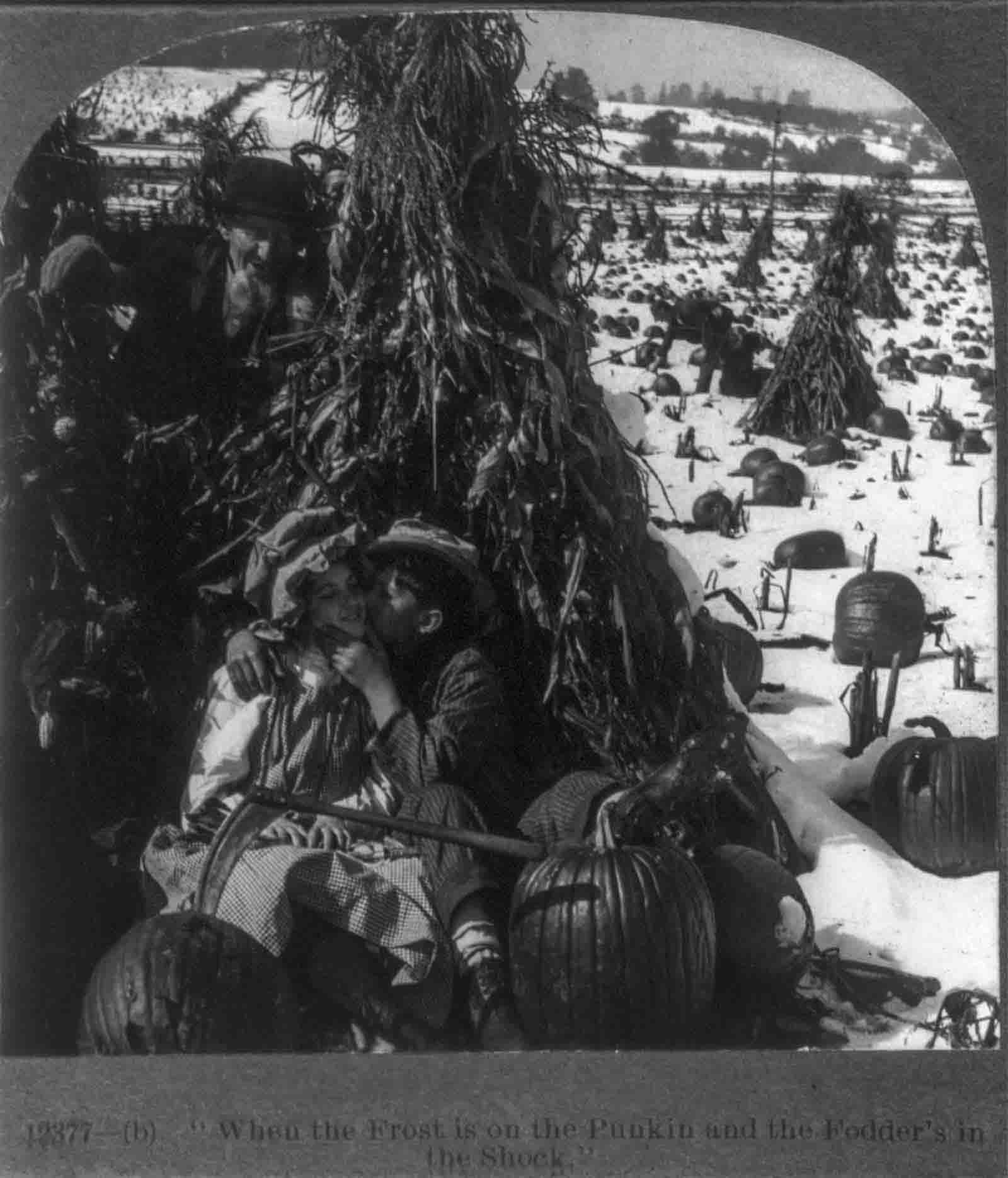

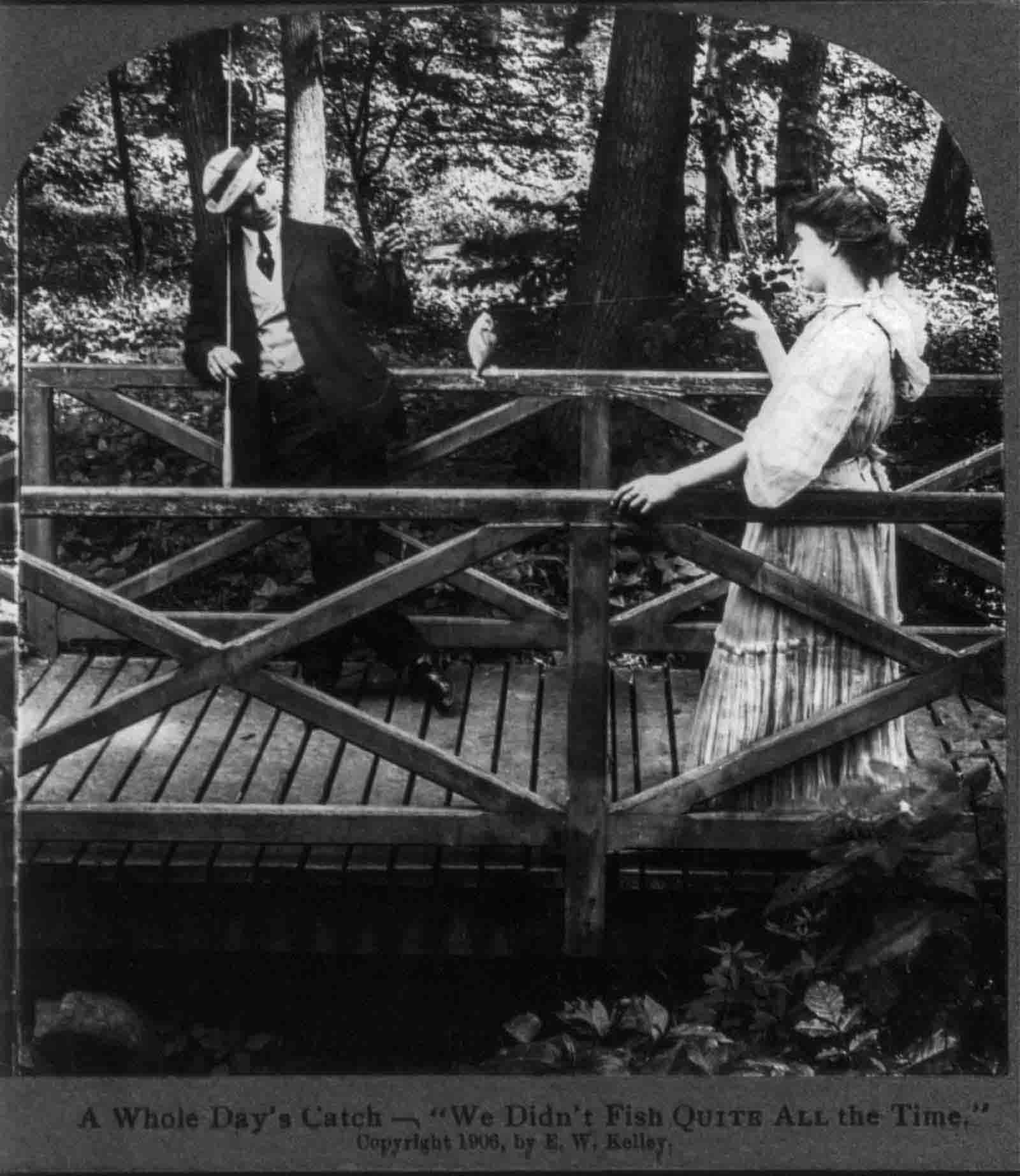

The earliest stereoscopes, “both with reflecting mirrors and with refracting prisms”, were invented by Sir Charles Wheatstone and constructed for him by optician R. Murray in 1832. He discovered the illusion that if you drew two pictures of something—say, a cube, or a tree—from two slightly different perspectives, and then viewed each one through a different eye, your brain would assemble them into a three-dimensional view. Stereoscopy was improved by Sir David Brewster in 1849. The production of the stereograph entailed making two images of the same subject, usually with a camera with two lenses placed 2.5 inches (6 cm) apart to simulate the position of the human eyes, and then mounting the positive prints side by side laterally on a stiff backing. Brewster devised a stereoscope through which the finished stereograph could be viewed; the stereoscope had two eyepieces through which the laterally mounted images, placed in a holder in front of the lenses, were viewed. The two images were brought together by the effort of the human brain to create an illusion of three-dimensionality. Millions of stereoview cards were sold and a stereoscope kept in the parlor was a common entertainment item for decades. Images on the cards ranged from portraits of popular figures to comical incidents to spectacular scenic views. When executed by talented photographers, stereoview cards could make scenes appear extremely realistic. For example, a stereographic image shot from a tower of the Brooklyn Bridge during its construction, when viewed with the proper lenses, makes the viewer feel as if they are about to step out on a precarious rope footbridge. Some stereoview cards focused on themes, including humor and romance. This group of comedic courtship cards from the turn of the century centers on the furtive romantic lives of farmhands and domestic servants and features scenes running the emotional gamut from chaste and poetic to unexpectedly raunchy and suggestive. The history of stereoscopy has been a succession of ups and down, a regular rollercoaster ride, from the very start to the present day. The first golden age of stereo photography ended after the 1862 exhibition, mostly on account of the advent of the carte-de-visite, a type of small photograph. T he second golden age took place at the end of the century and most views at the time came from the United States. Cinema killed the interest in stereo photography, which was shortly revived after the First World War (there are thousands of stereos depicting the war). Large archives of them still exist and thousands of them can be viewed online.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe