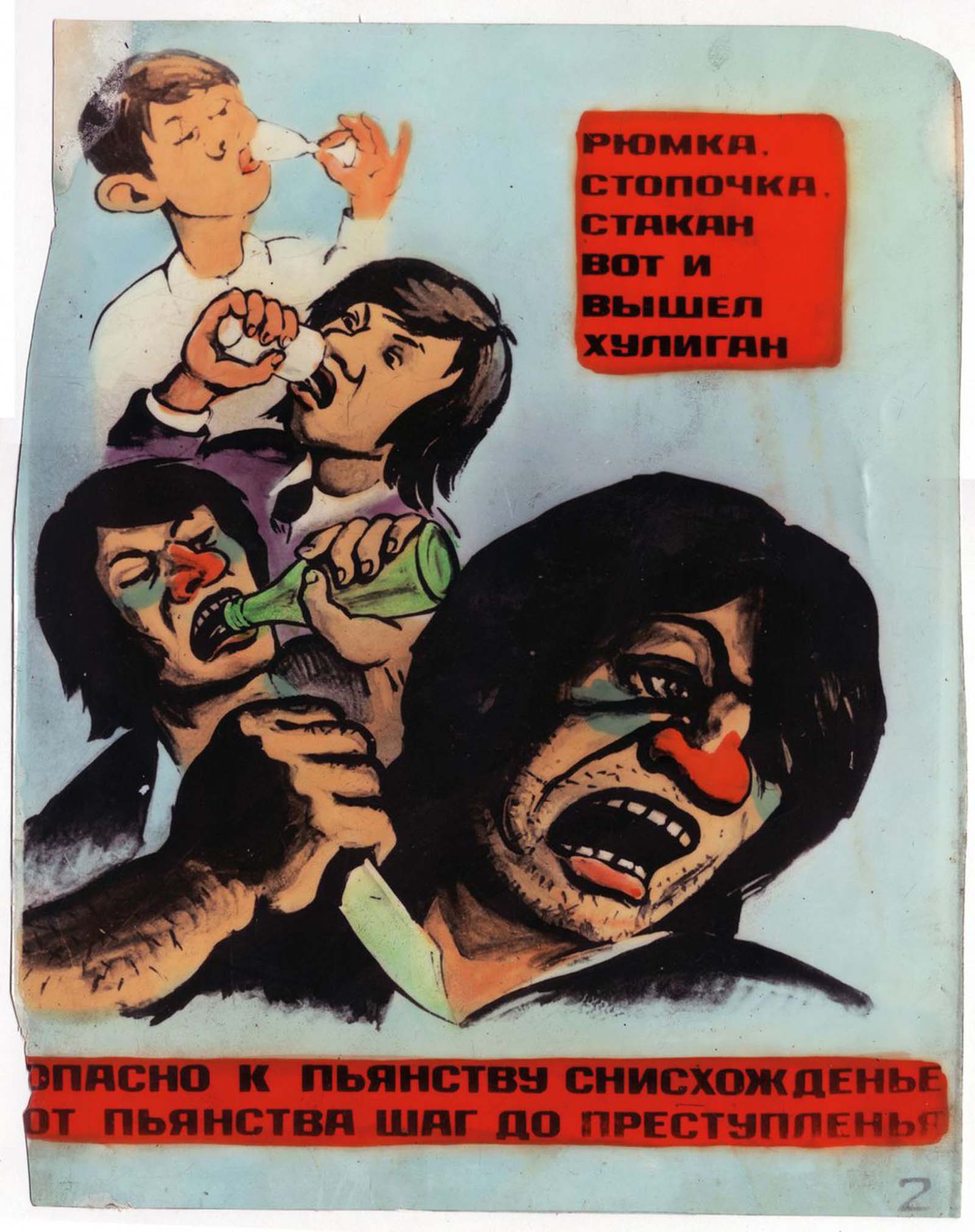

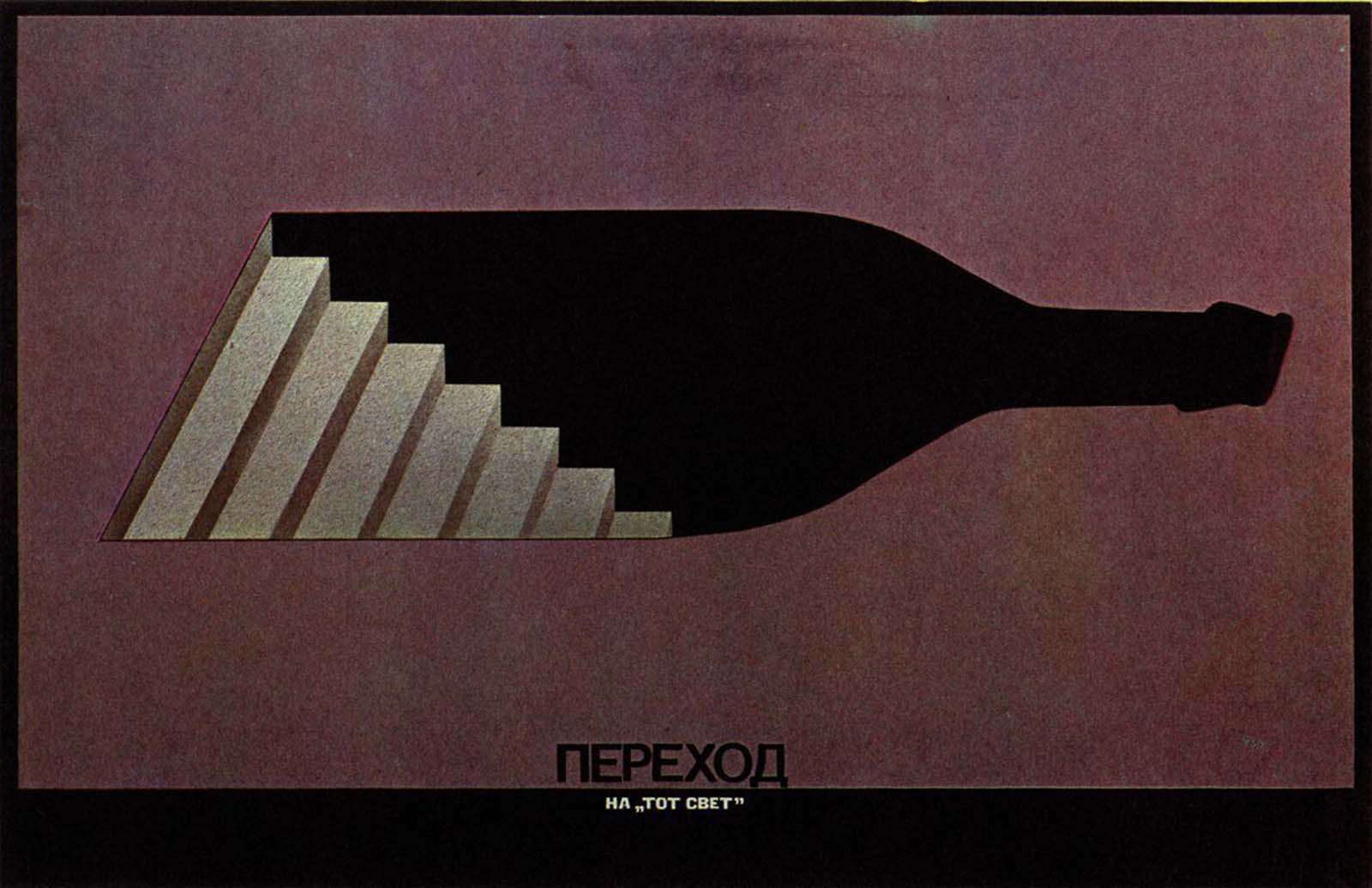

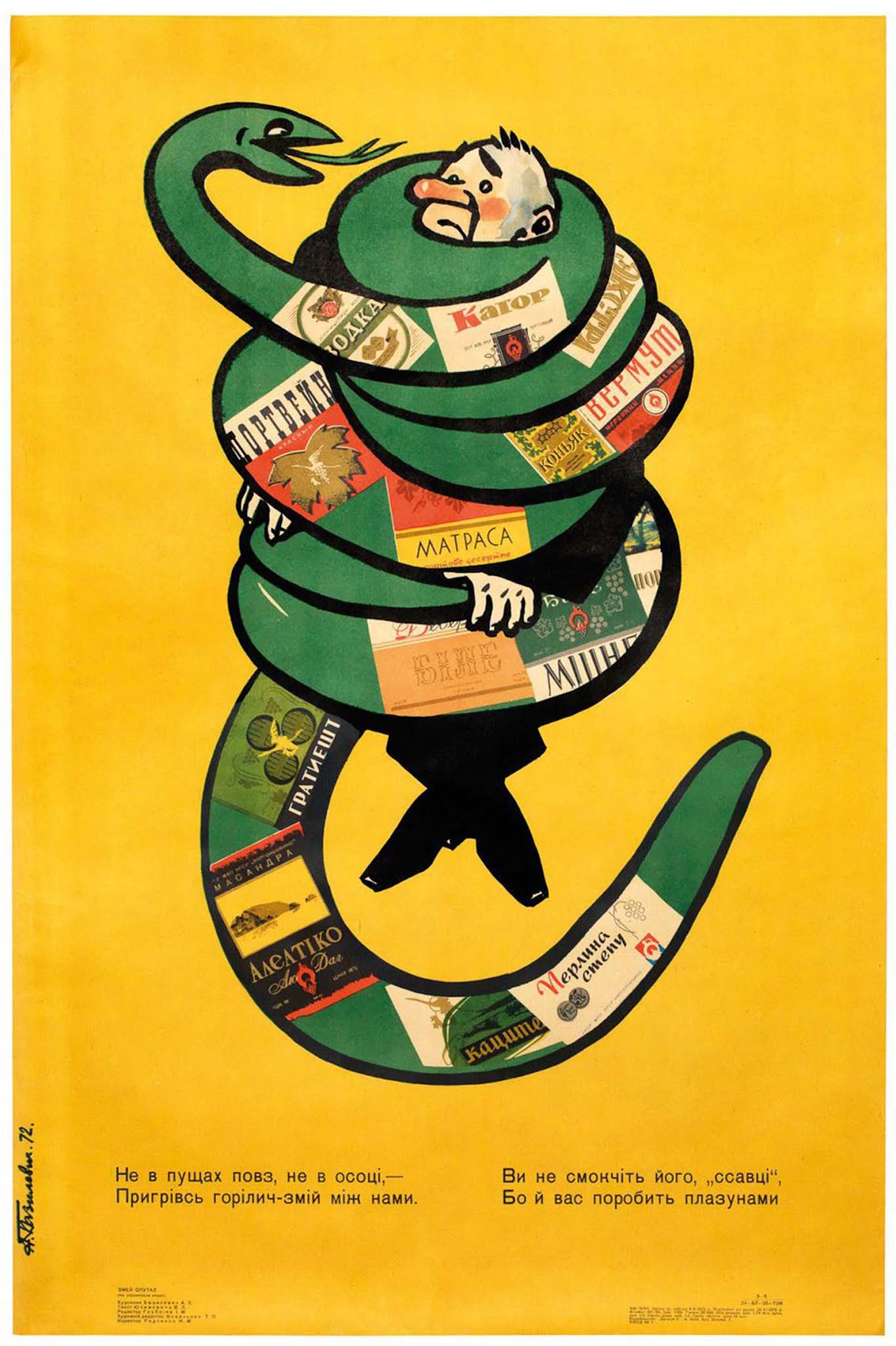

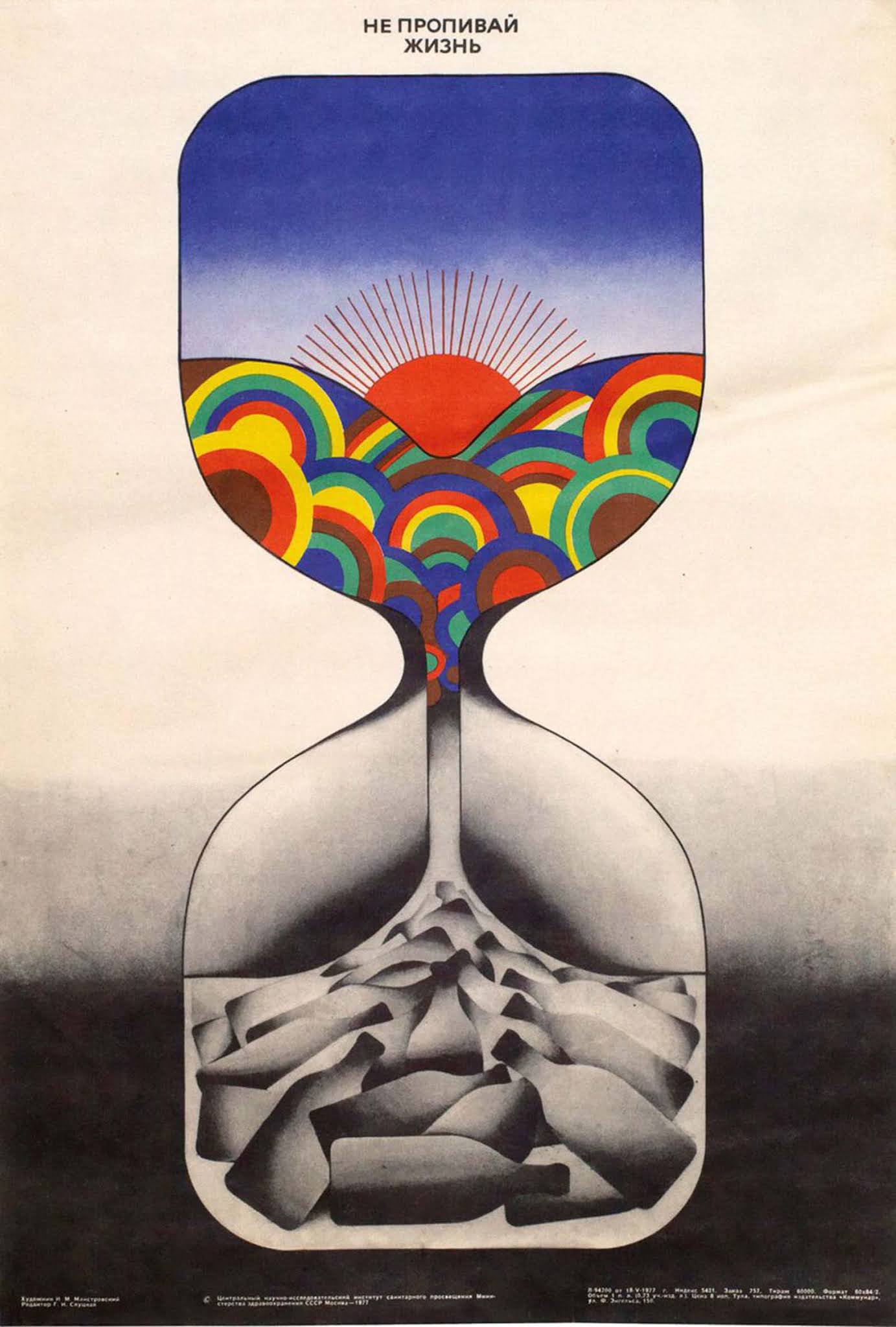

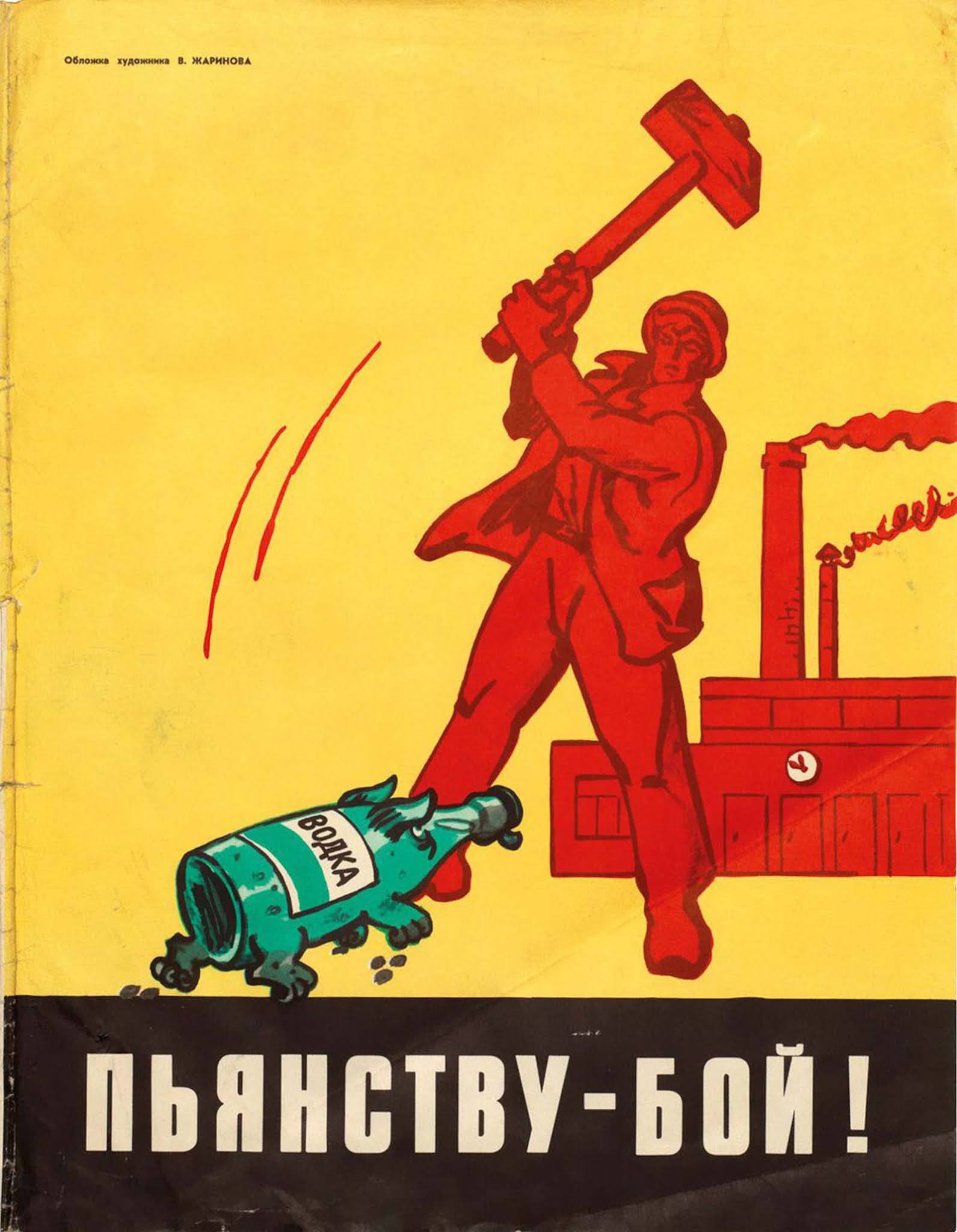

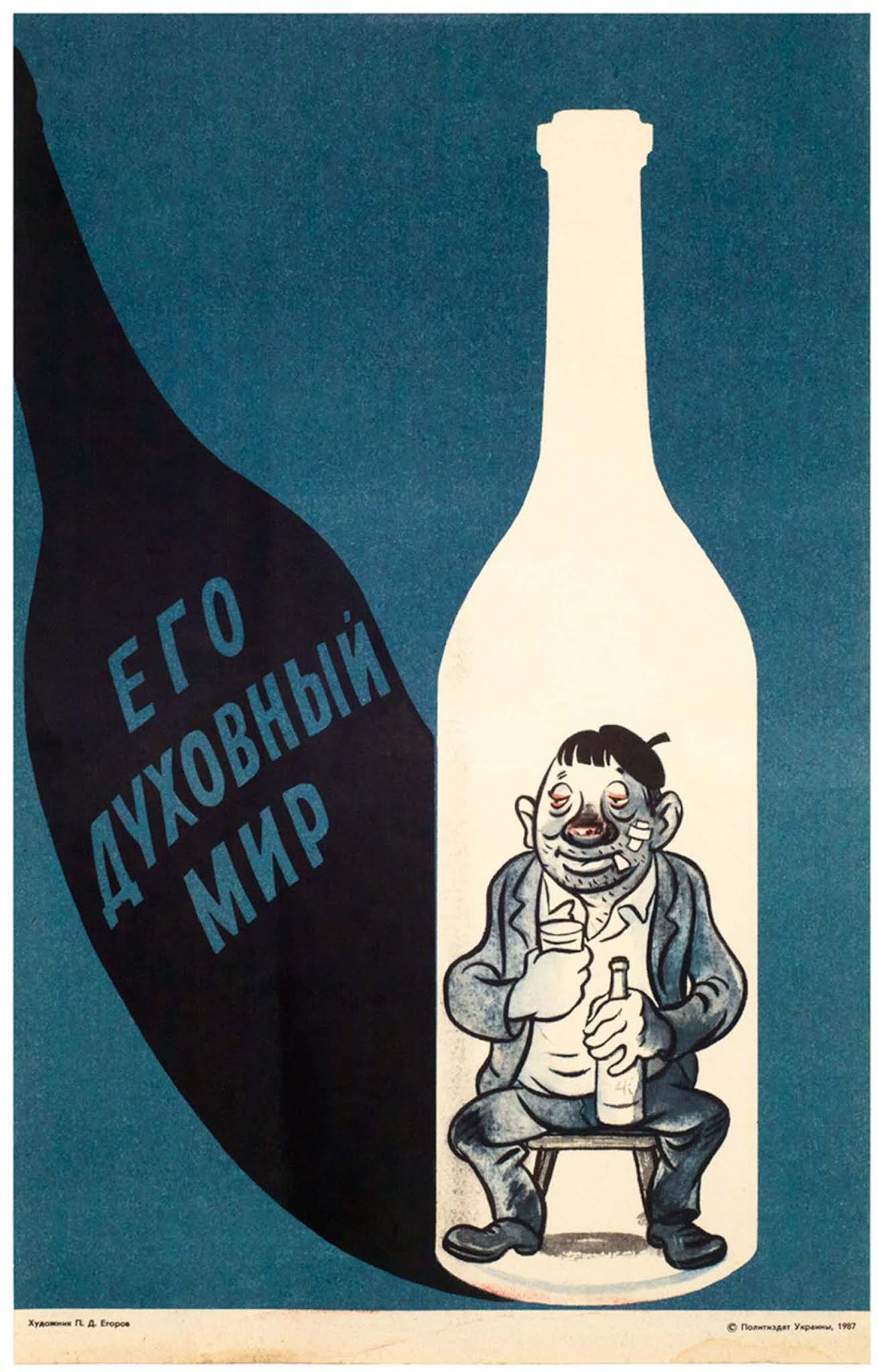

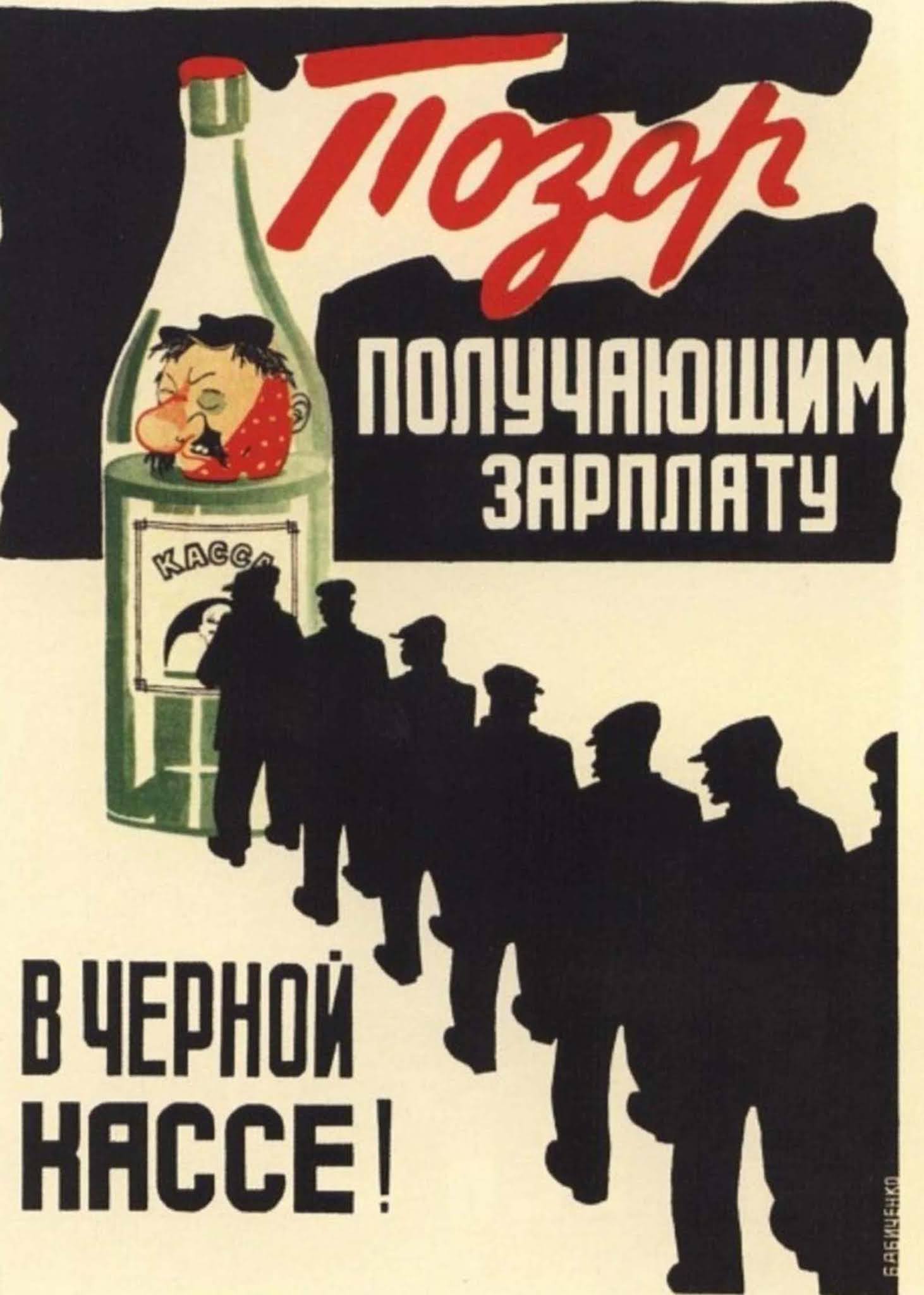

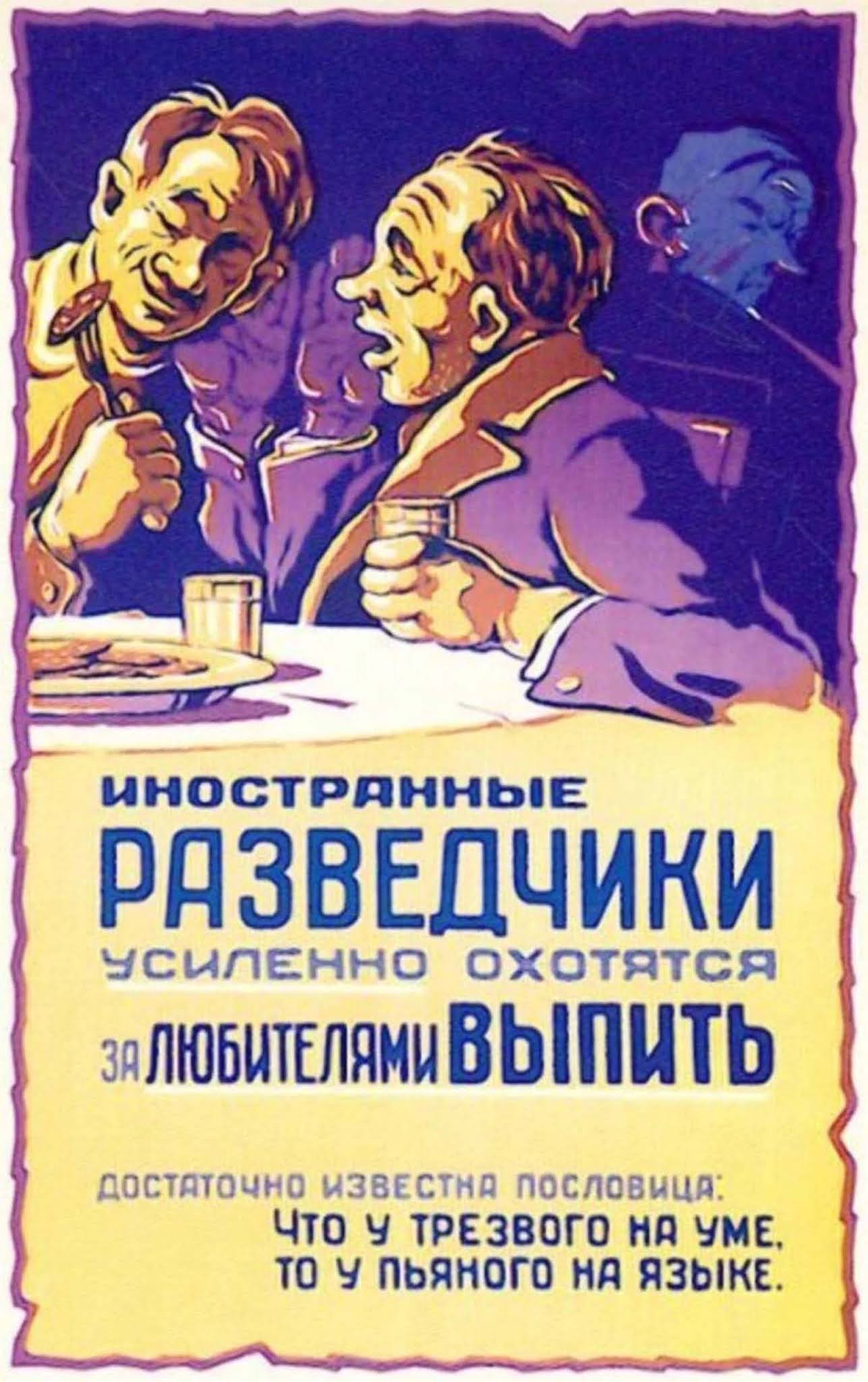

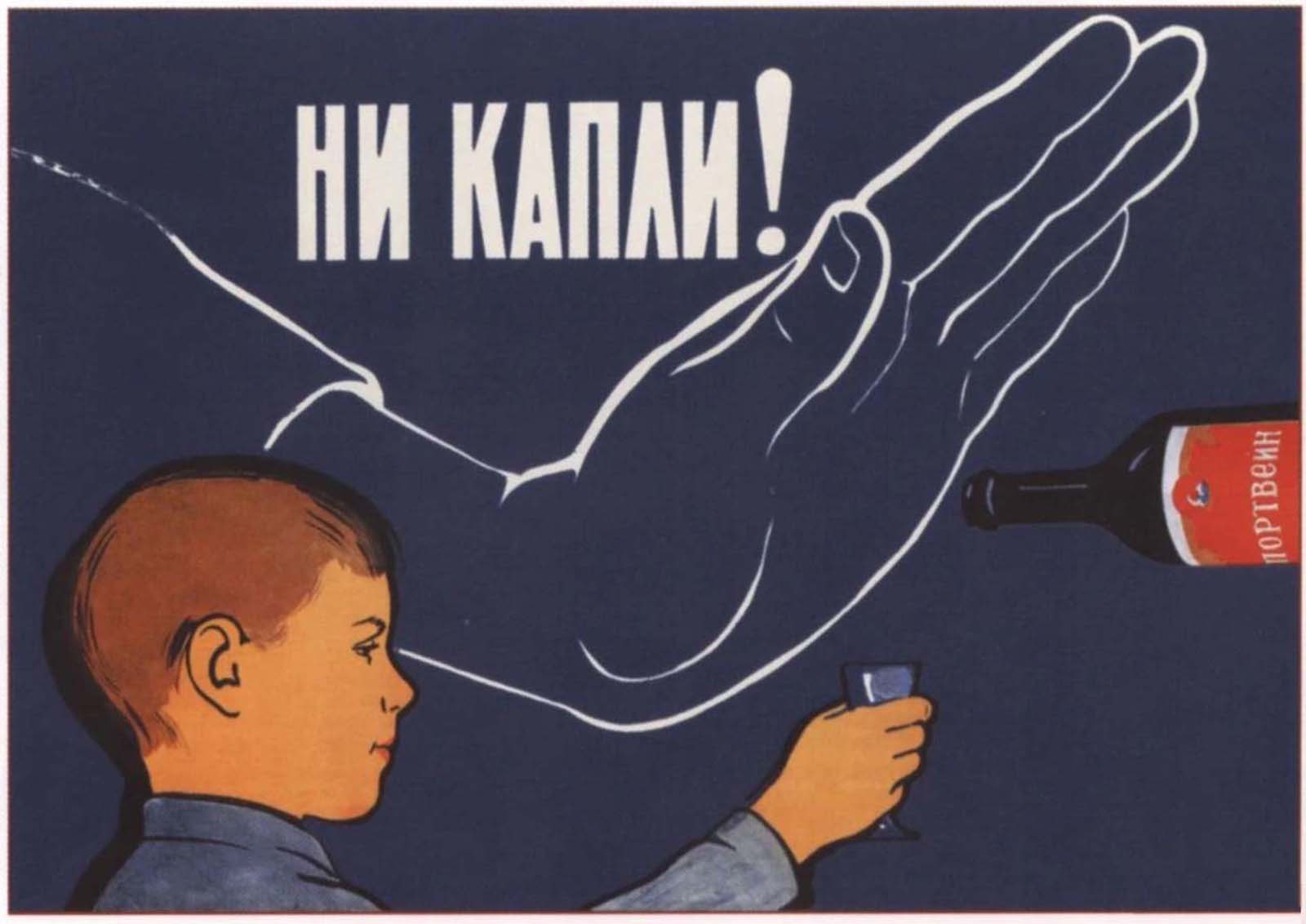

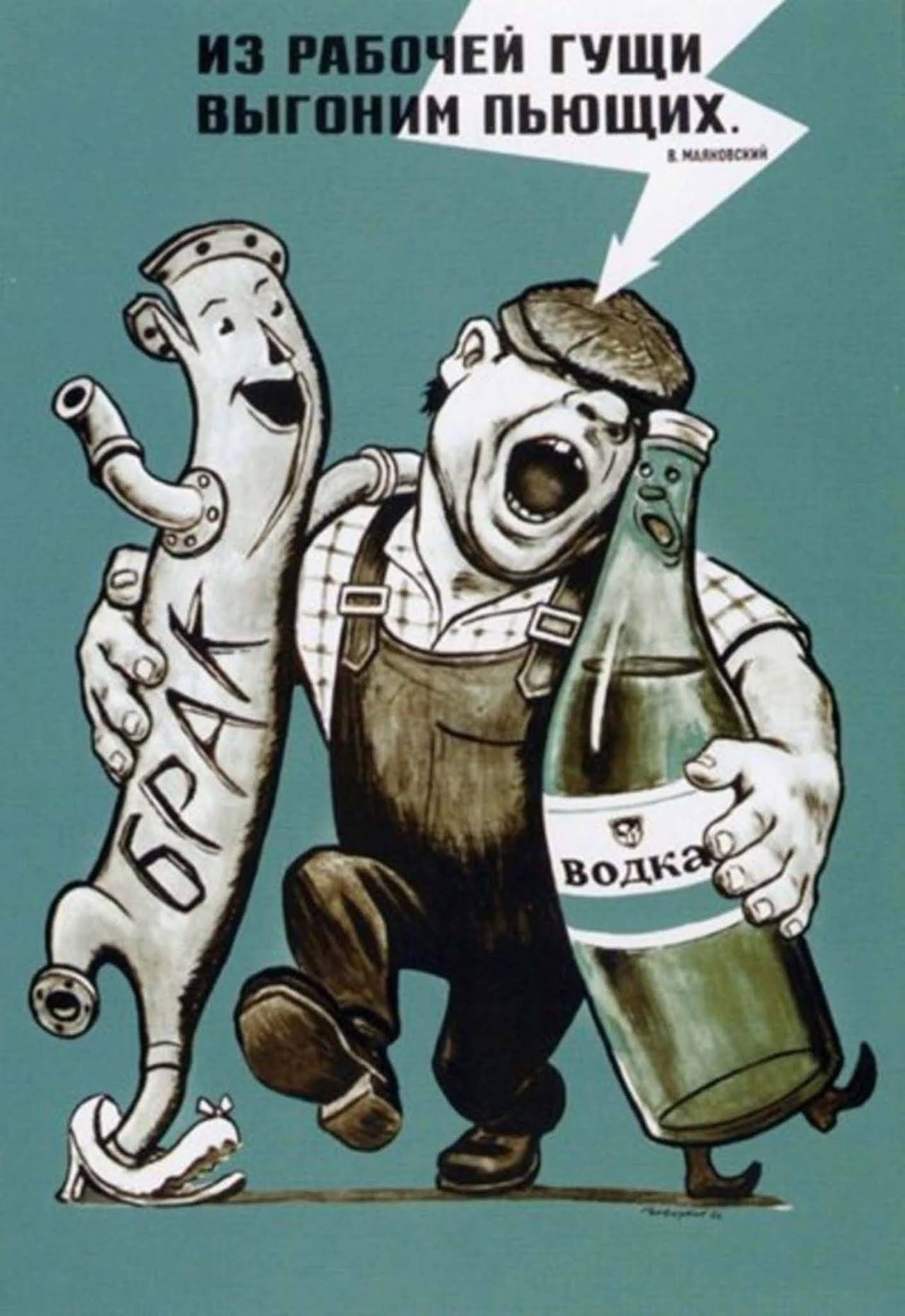

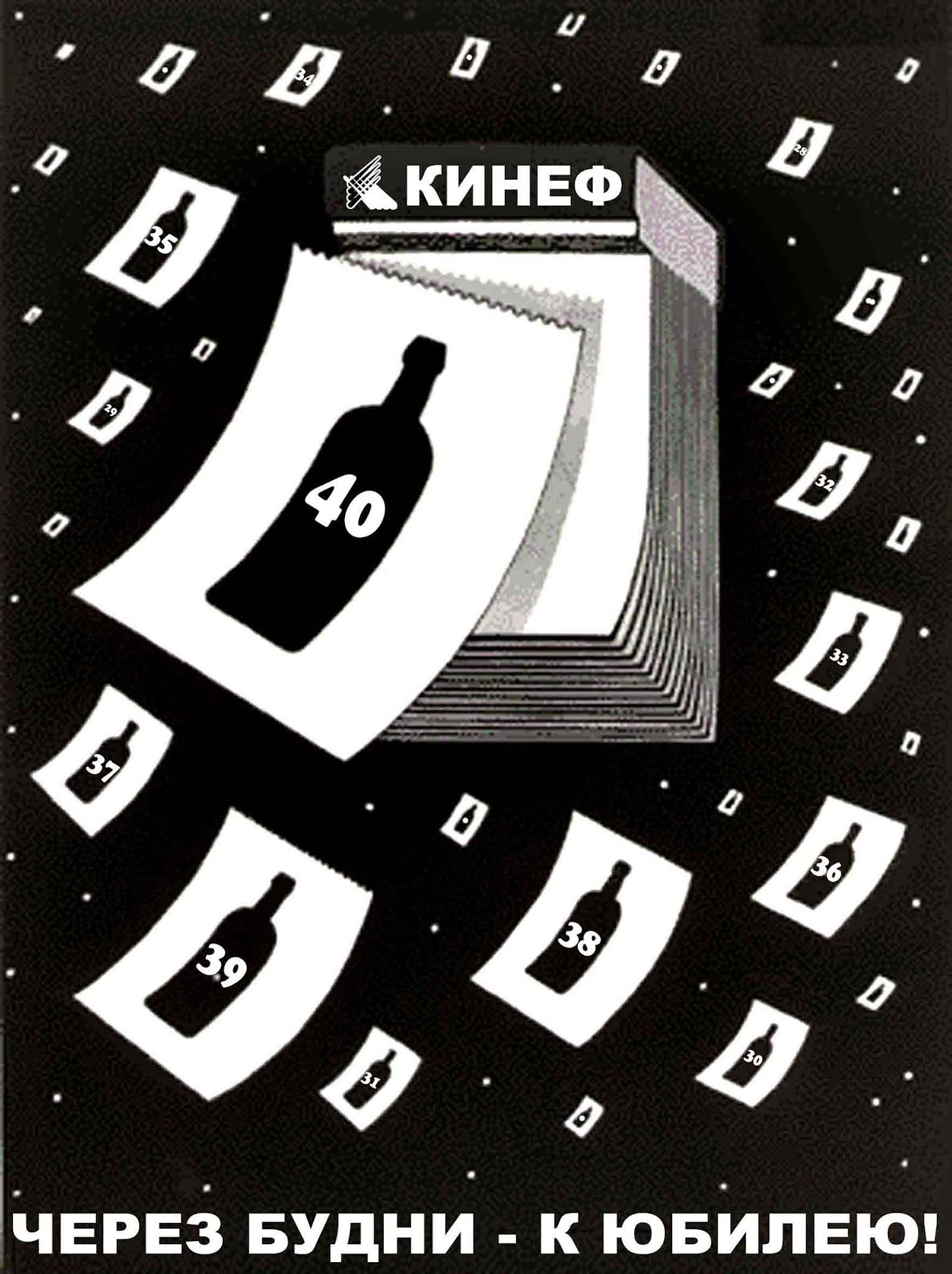

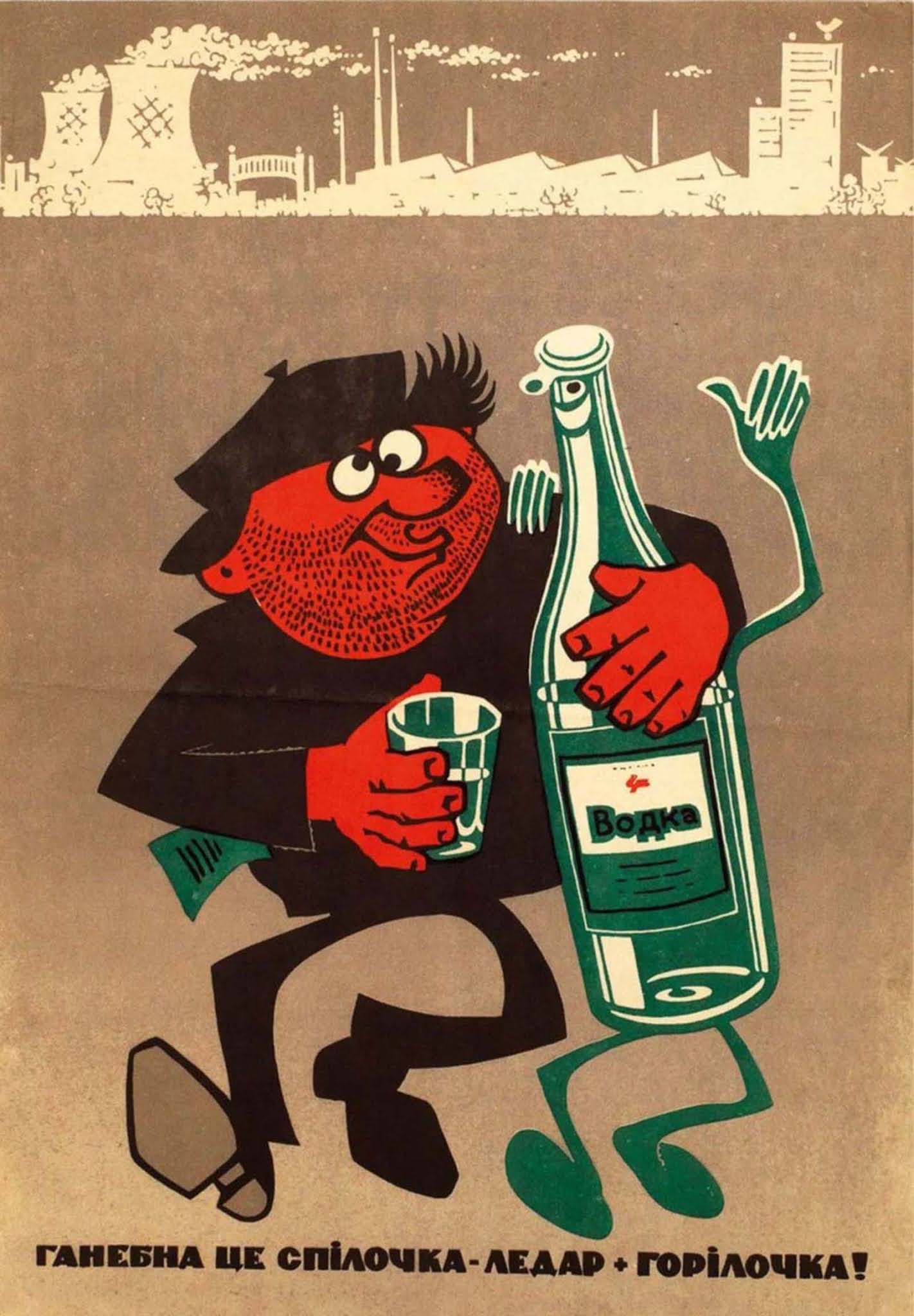

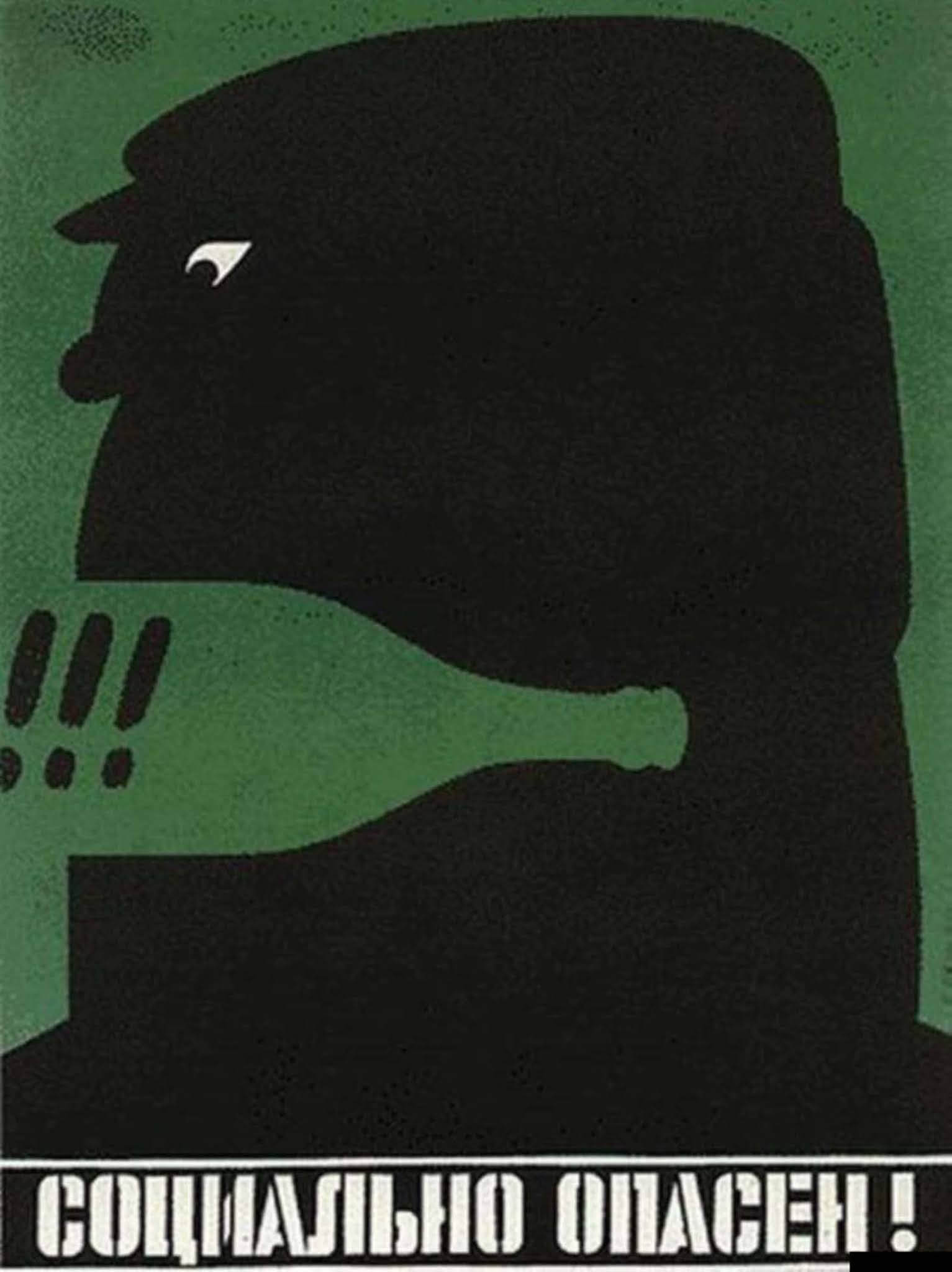

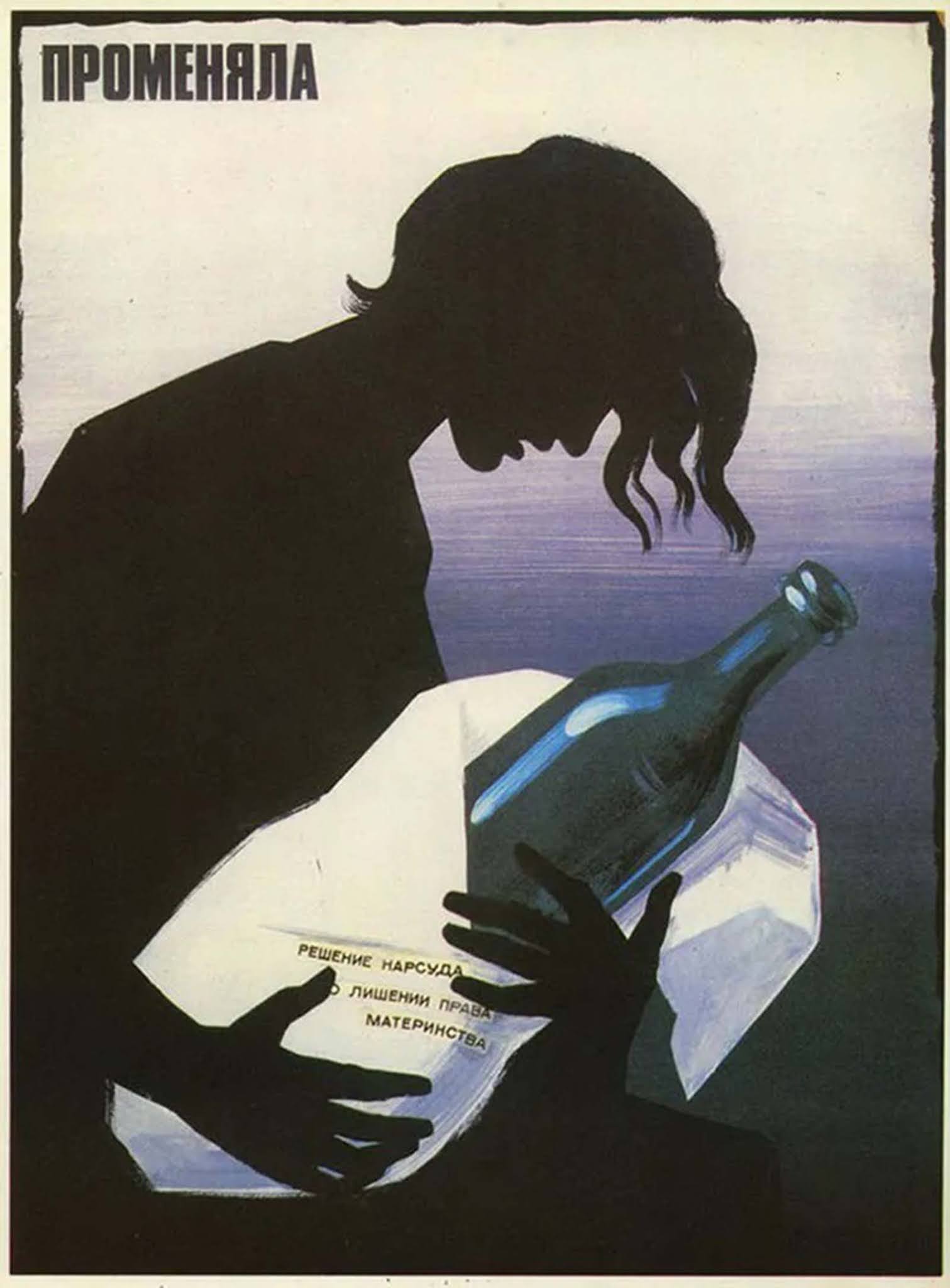

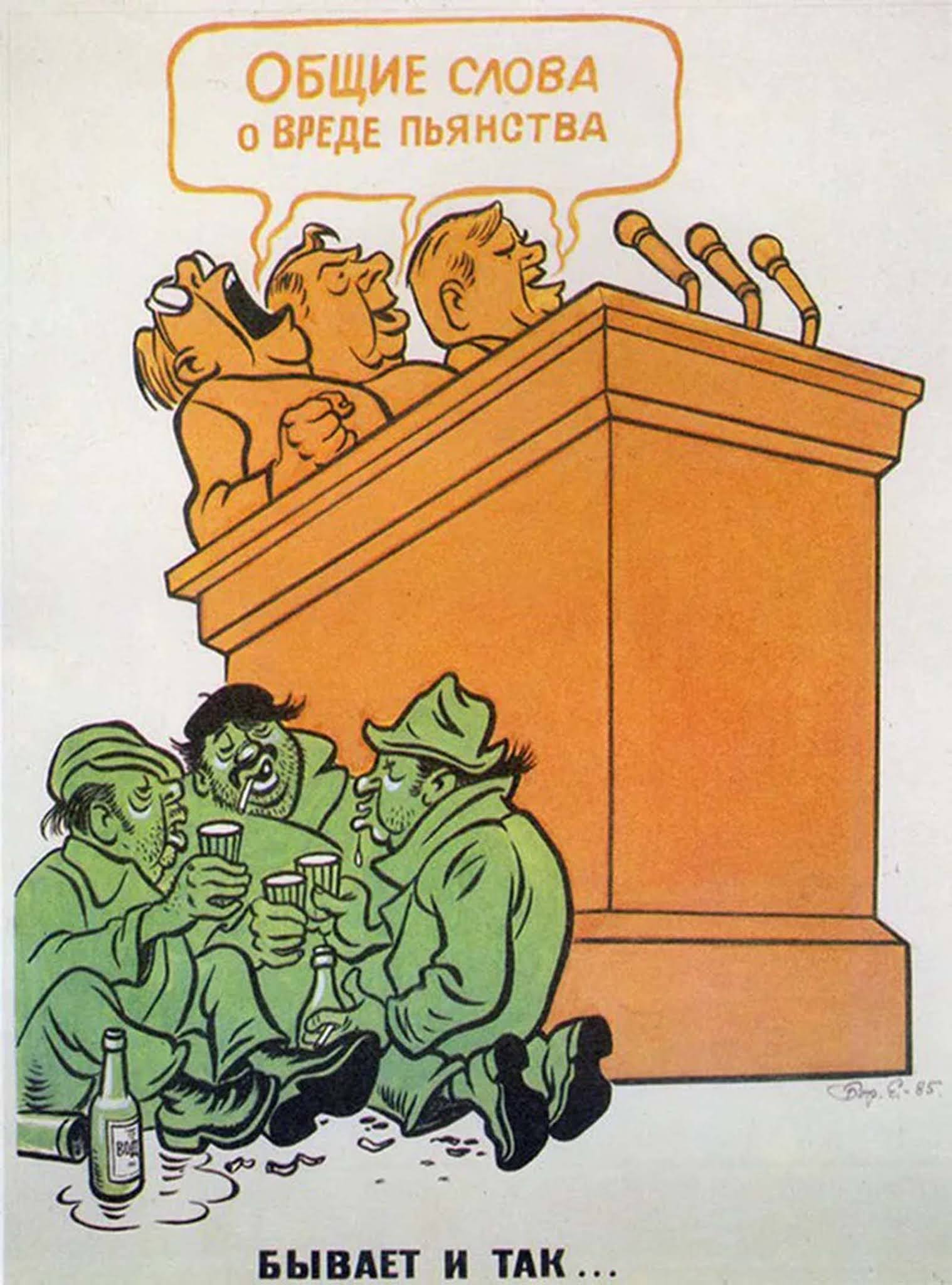

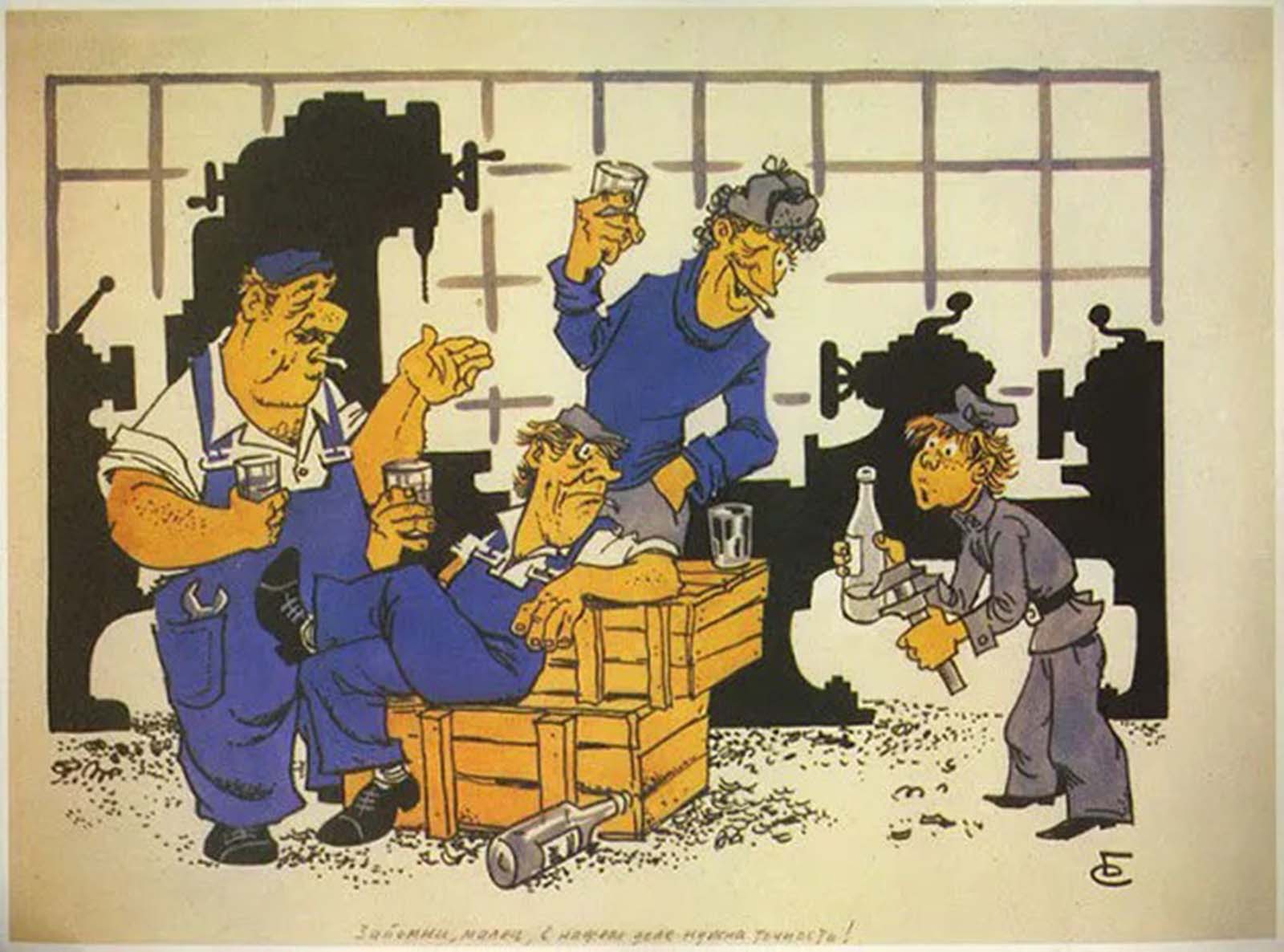

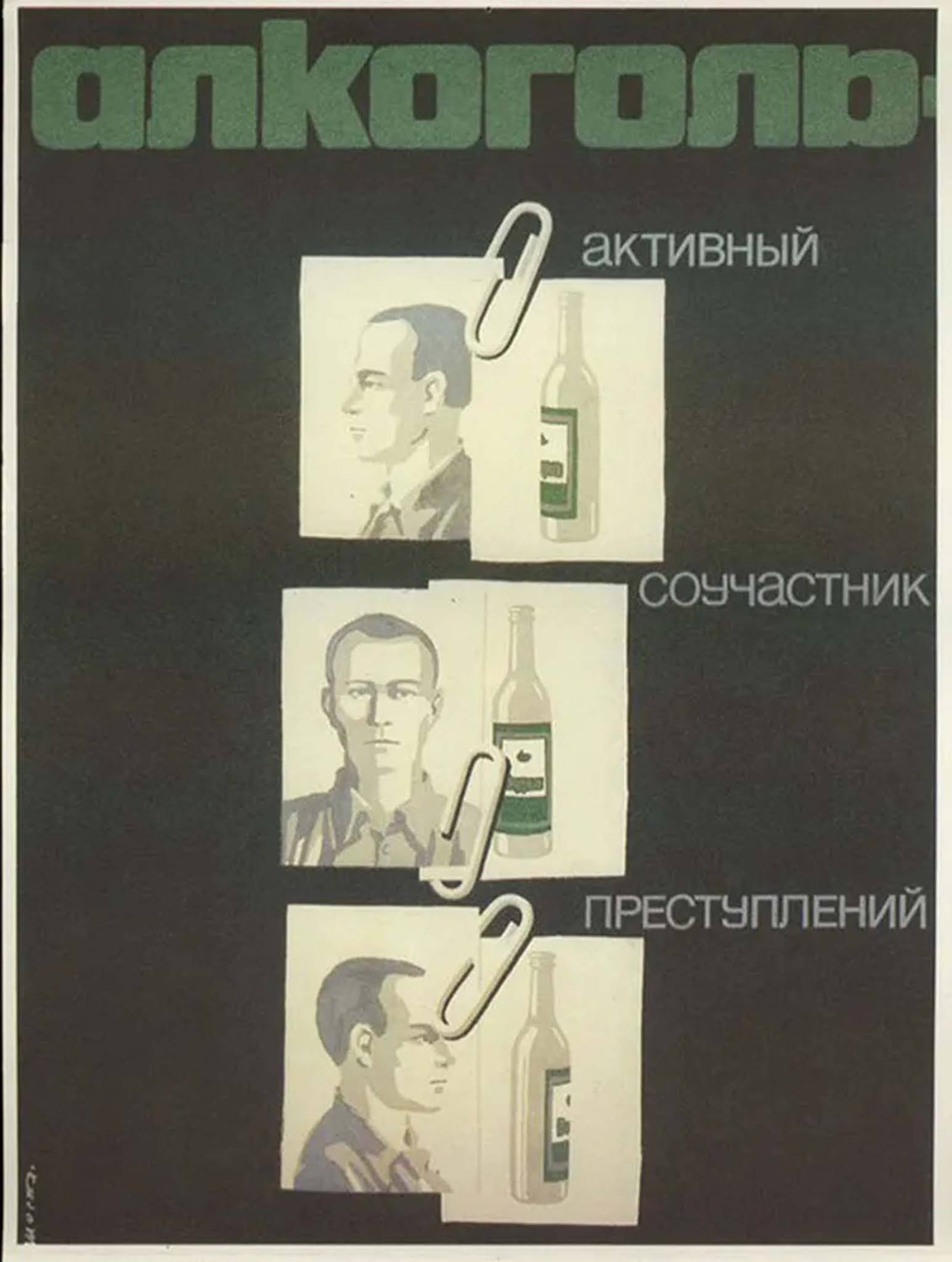

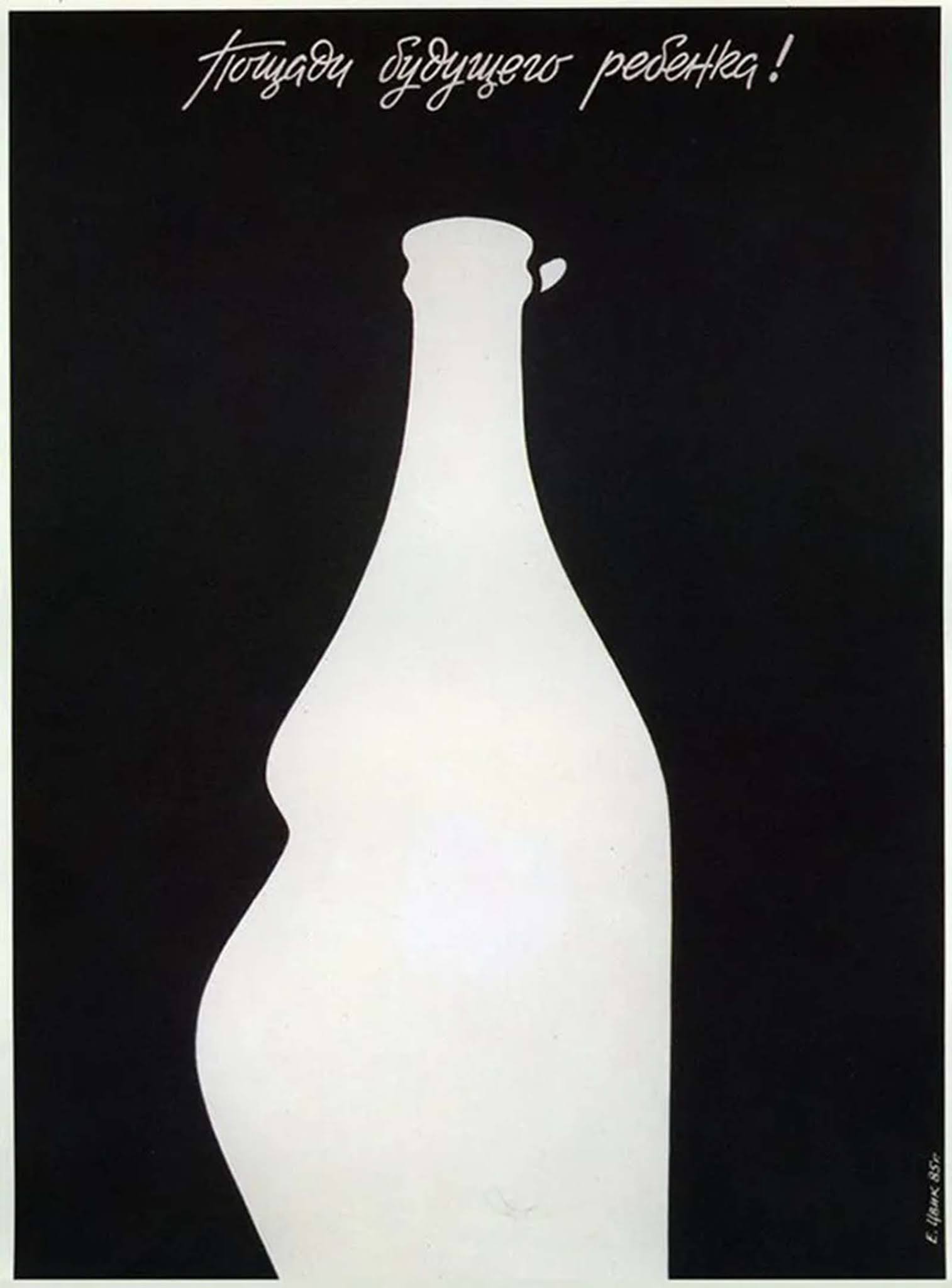

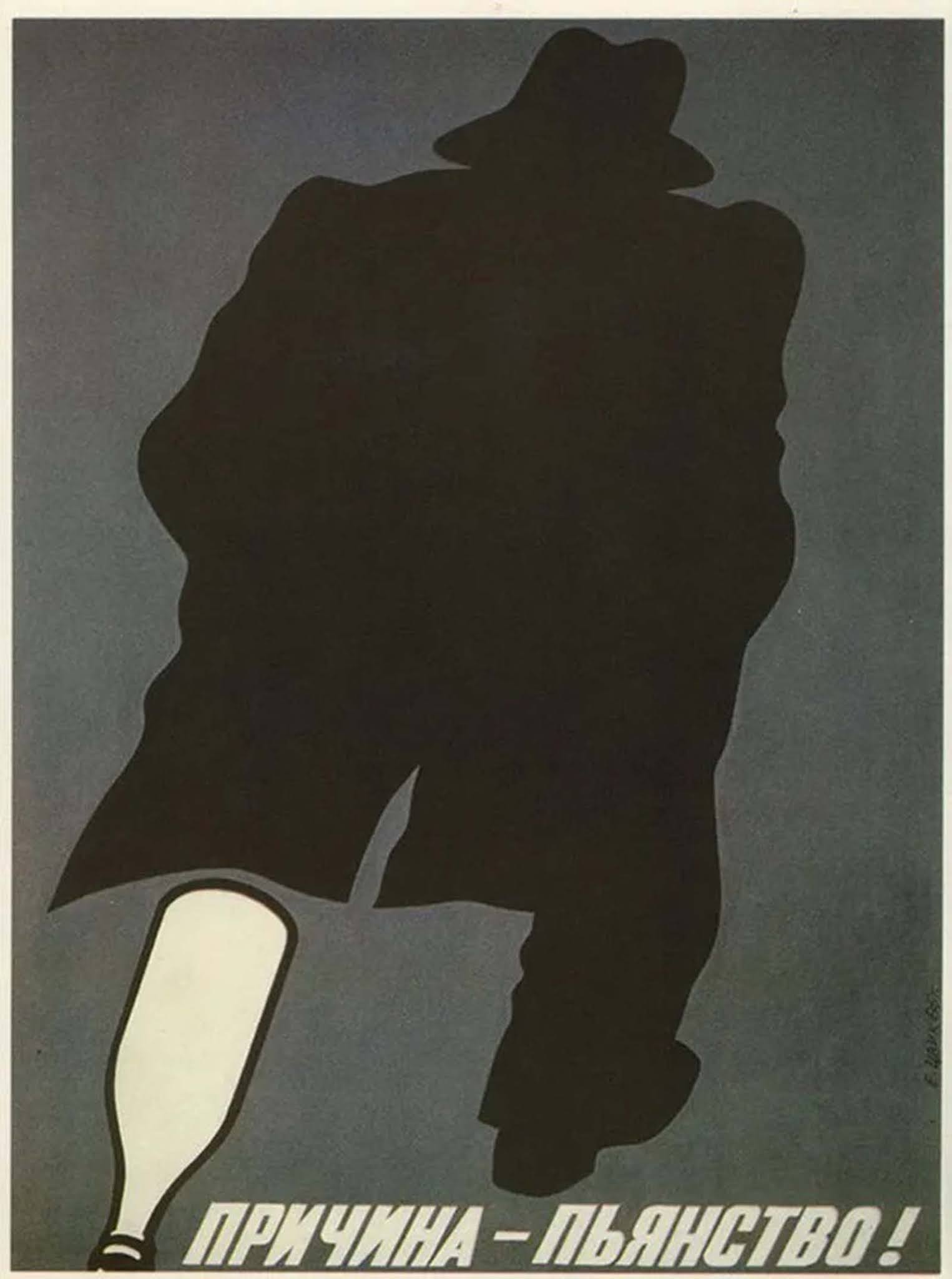

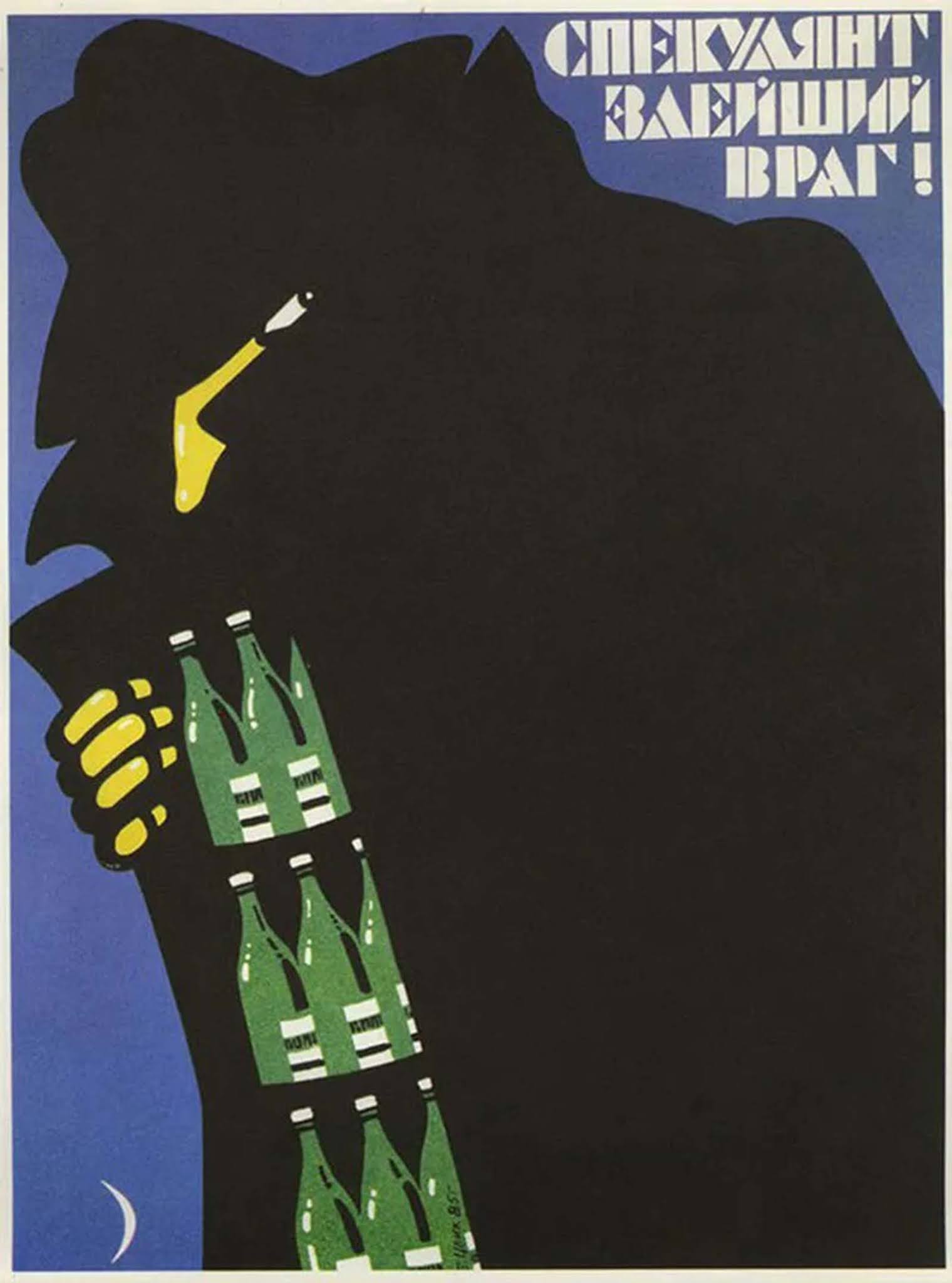

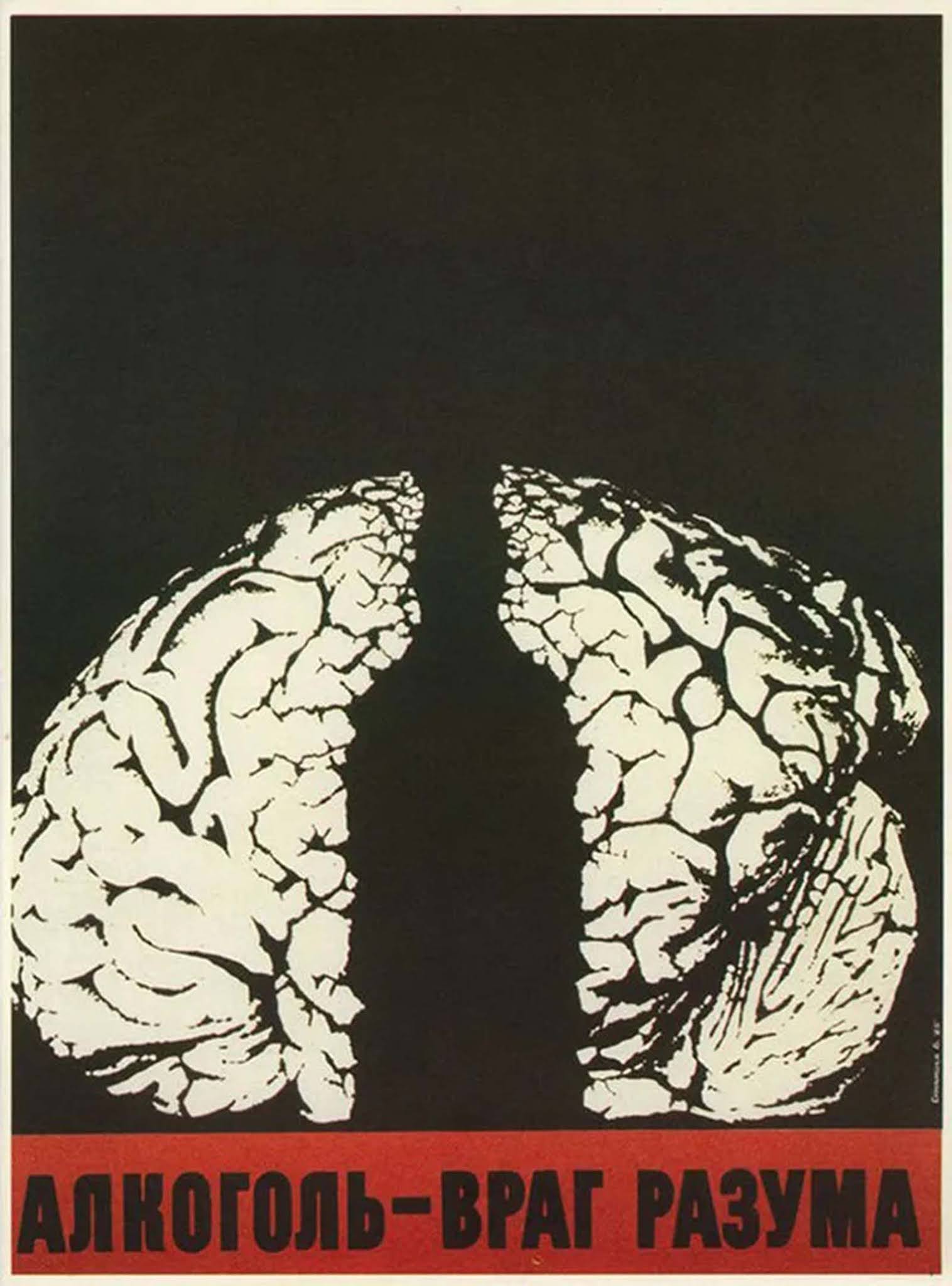

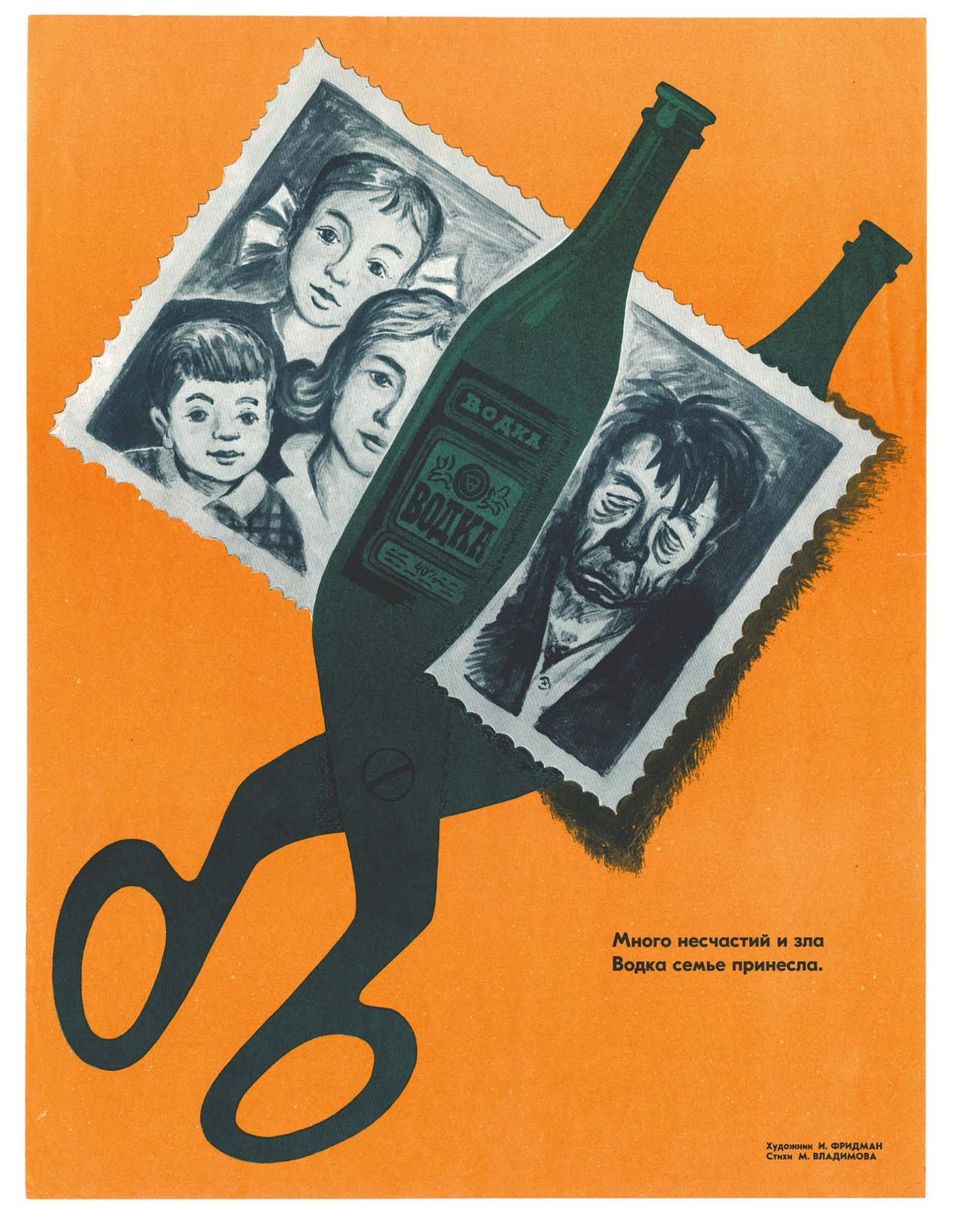

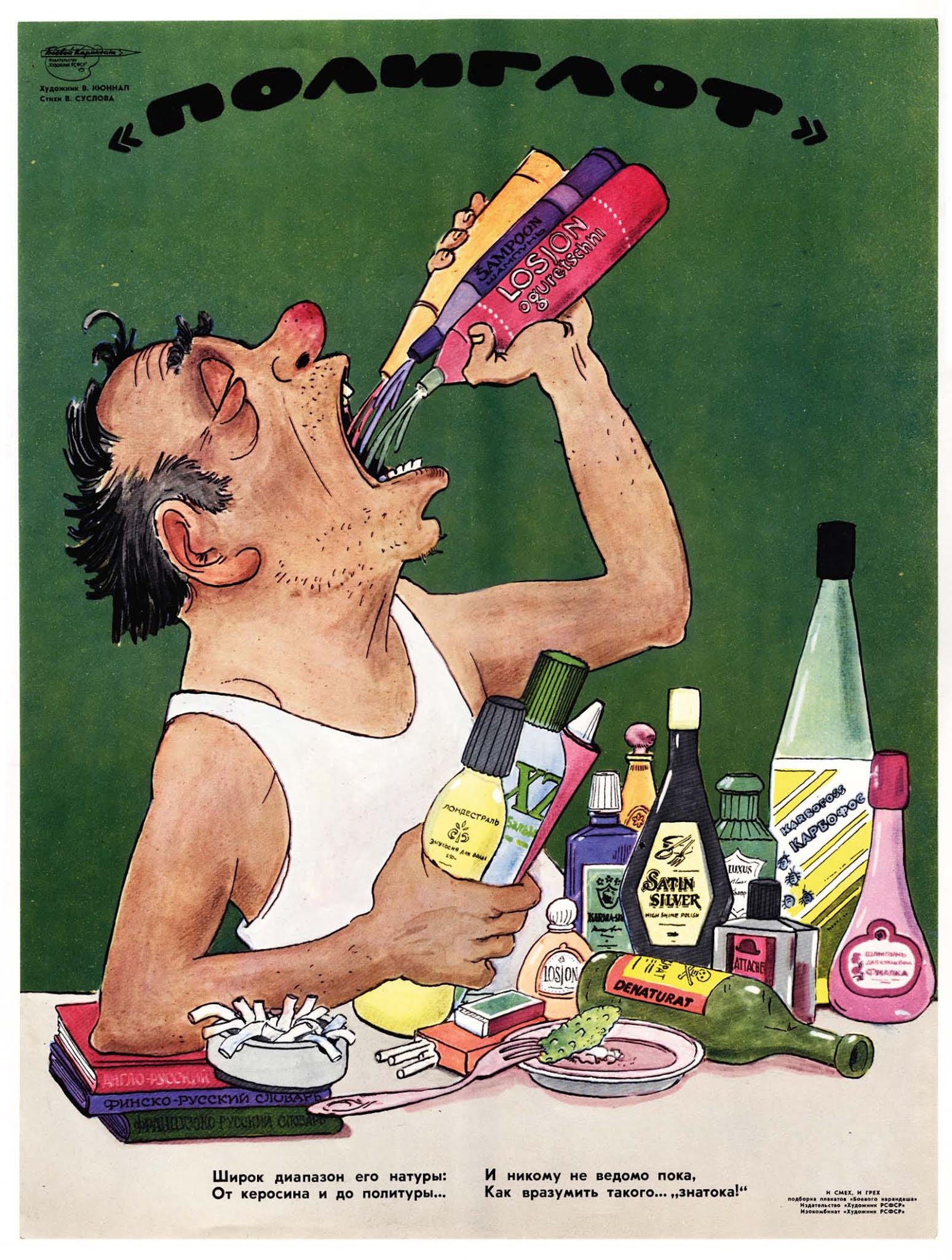

It was a forceful and ruthless campaign, which included a variety of measures from the promotion of fruit juice drinking to price rises on vodka, the closing of vodka distilleries and the up-rooting of century-old vines in Georgia, amounting in fact to semi prohibition. Soviet communist officials firmly believed that heavy drinking and alcohol abuse were historical products of bourgeois-capitalist institutions and as such should ultimately disappear in a ”classless” and “conflict-free” socialist society. However, the alcohol issue was never very high on the government agenda. What alcohol abuse remained in the new Soviet society was viewed as stemming from character flaws of the individual, absence of personal willpower, peer pressures, alien (foreign) influences, and the like, but was not believed to be related to systemic features of the society. Contrary to all evidence (and disregarding cause-and-effect considerations), it was also assumed that alcohol abuse and heavy drinking were associated with low educational, “cultural”, and income levels. Gorbachev’s 1985 anti-alcohol campaign began with cuts in the production and sale of alcoholic beverages, combined with hefty price increases and a number of administrative penalties for alcohol abuse. A public information campaign was also started where posters were placed in workplaces and public spaces depicting the dangers of alcohol and the benefits of not drinking it. These posters would go on to have a limited effect on the already heavily ingrained drinking culture of the Soviet citizens. In 3 years, per capita consumption of state-produced alcoholic beverages was cut by a remarkably high 67 percent. However, one of the most important downfalls of this campaign was the drastically decreased tax revenue from alcohol. With the new prices of alcohol being so high many Soviet citizens stopped buying alcohol from the state-owned shops, putting the already weak economy in a big budget deficit. The second problem was that many households began brewing their own moonshine, especially in the countryside, using very rudimentary tools. This not only created cheap alcohol but also badly filtered alcohol leading to an even bigger health crisis developing as a result of this borderline poison now being consumed. By 1987 it was clear that the anti-alcohol campaign utterly failed. Although, many statistical series on mortality, morbidity, and alcohol-related social disturbances showed significant and rapid improvement during the campaign. But, the general benefits slowly began to disappear. With the economy in ruin, Gorbachev had to reverse the changes he made in 1985 officially ending the campaign in 1987. Ten years after the start of the anti-alcohol campaign and on the occasion of its anniversary, Gorbachev gave an interview to Radio Liberty. The former general secretary explained that the launching of the campaign had been necessary because “they had made the country drunk as a way to solve budget problems” and expressed grief that “consumption of alcohol had reached 10.3 liters per person, including children and old people”. But the general secretary might have had access to the secret data of the Soviet State Statistical Committee on the actual consumption of alcohol, including illegal alcohol, showing consumption of 13.8 liters. Gorbachev asserted that the “resolution was moderate” and that “later people, fearful of losing their portfolios and chairs”, showed “real bolshevism at the stage of execution”. In this article, we’ve collected Soviet anti-alcohol posters from the 1960s through the 1980s. With striking, colorful graphics and stark metaphors, the posters cast alcoholism as a snake choking the life of vivacious young men. Drinkers grow slothful and lazy, abandon their families, endanger their coworkers, or become murderous brutes. Some of the posters and more can be found on Soviet Anti-Alcohol Posters by Fuel Publishing. (Photo credit: Russian Archives / Alcohol by Fuel Publishing / A Contemporary: History of Alcohol in Russia by Alexandr Nemtsov). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe