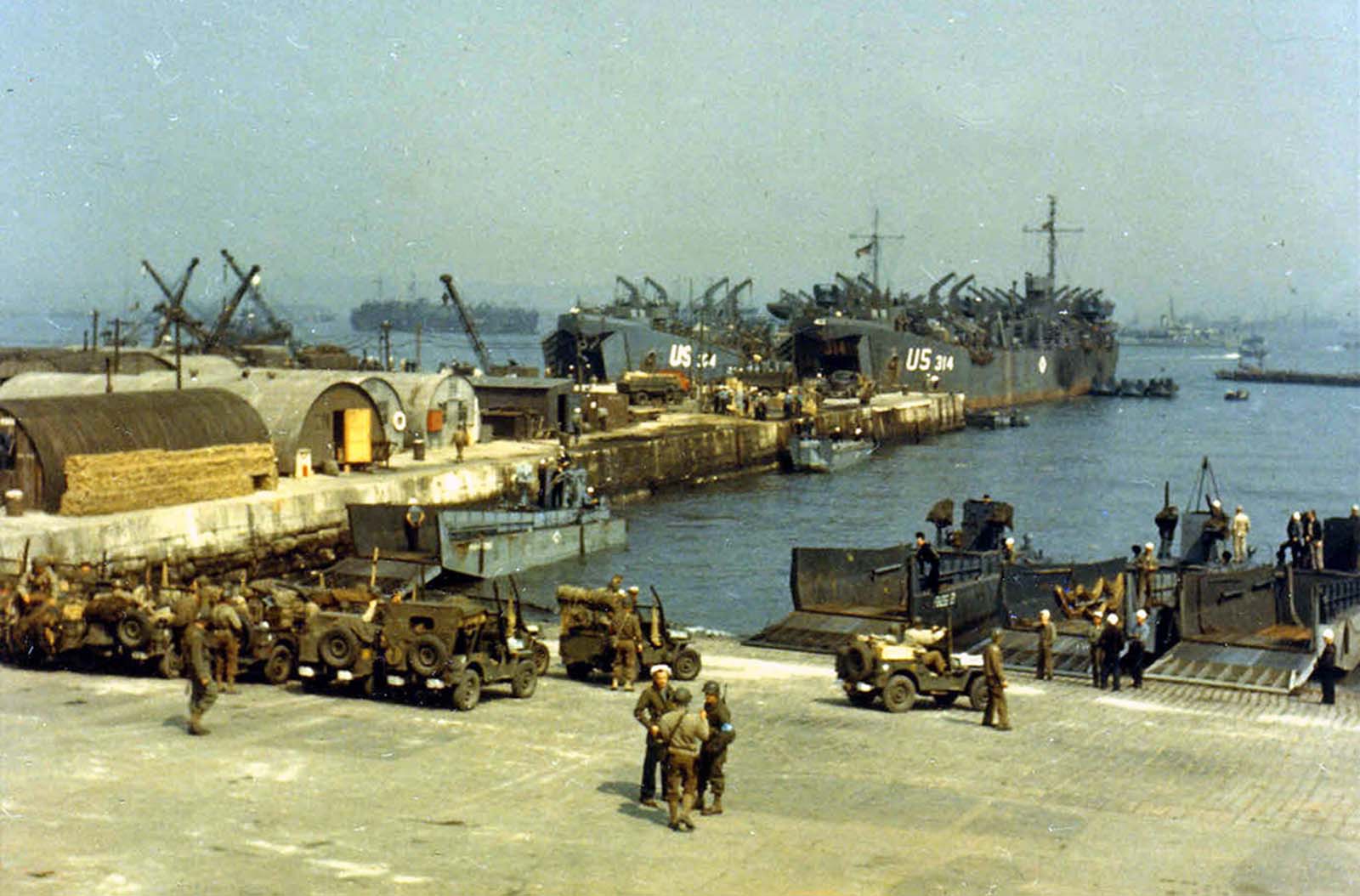

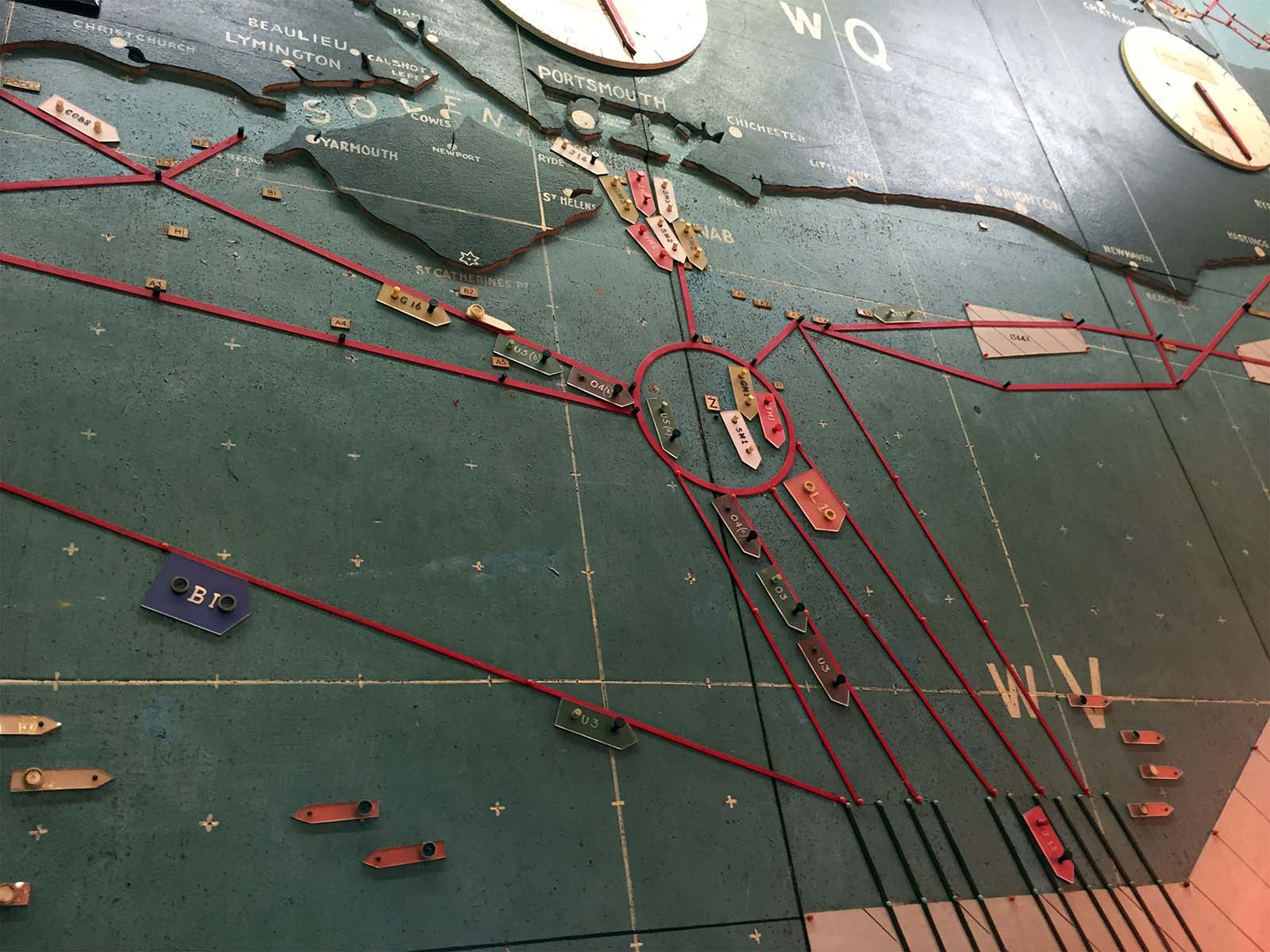

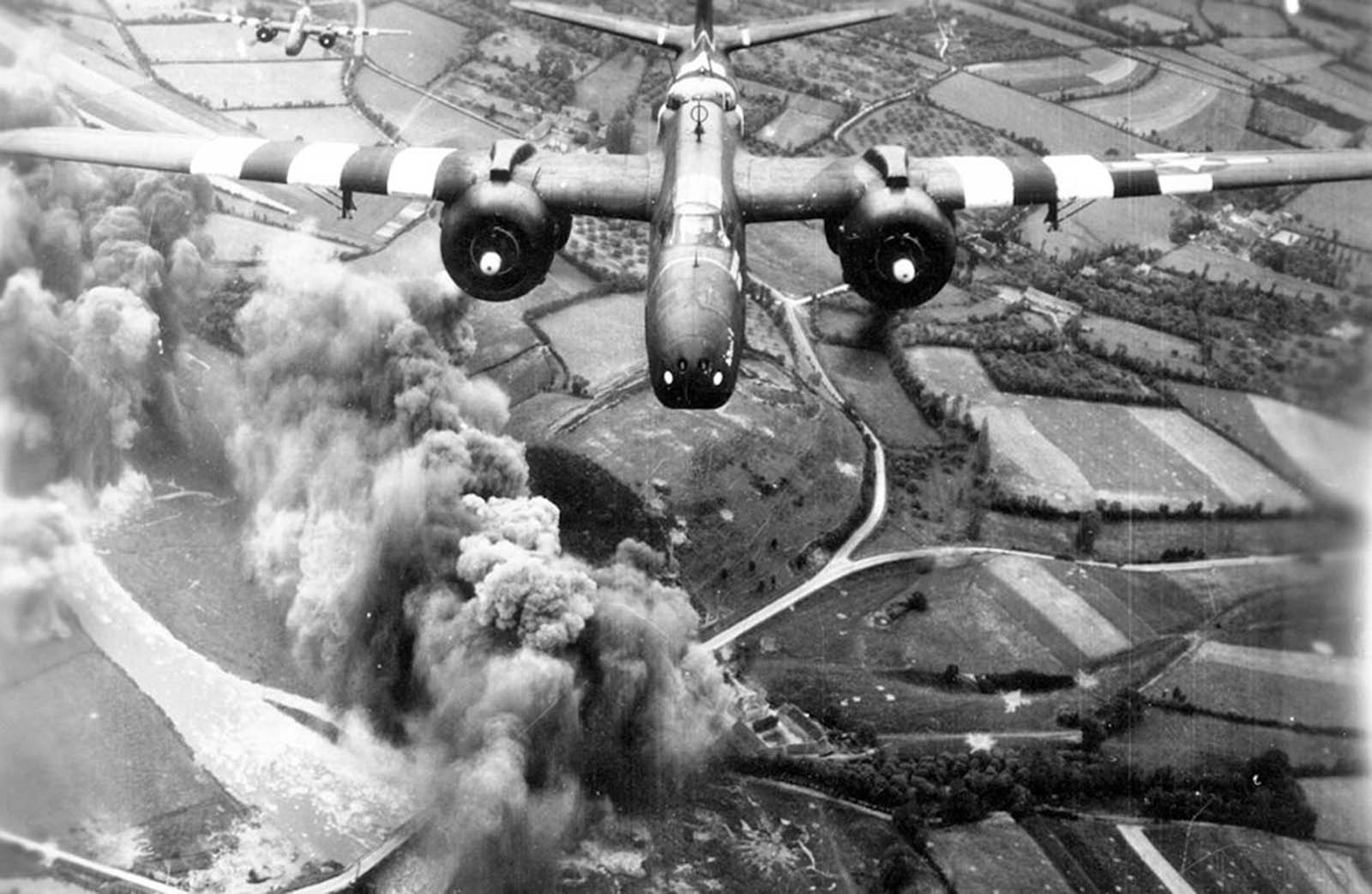

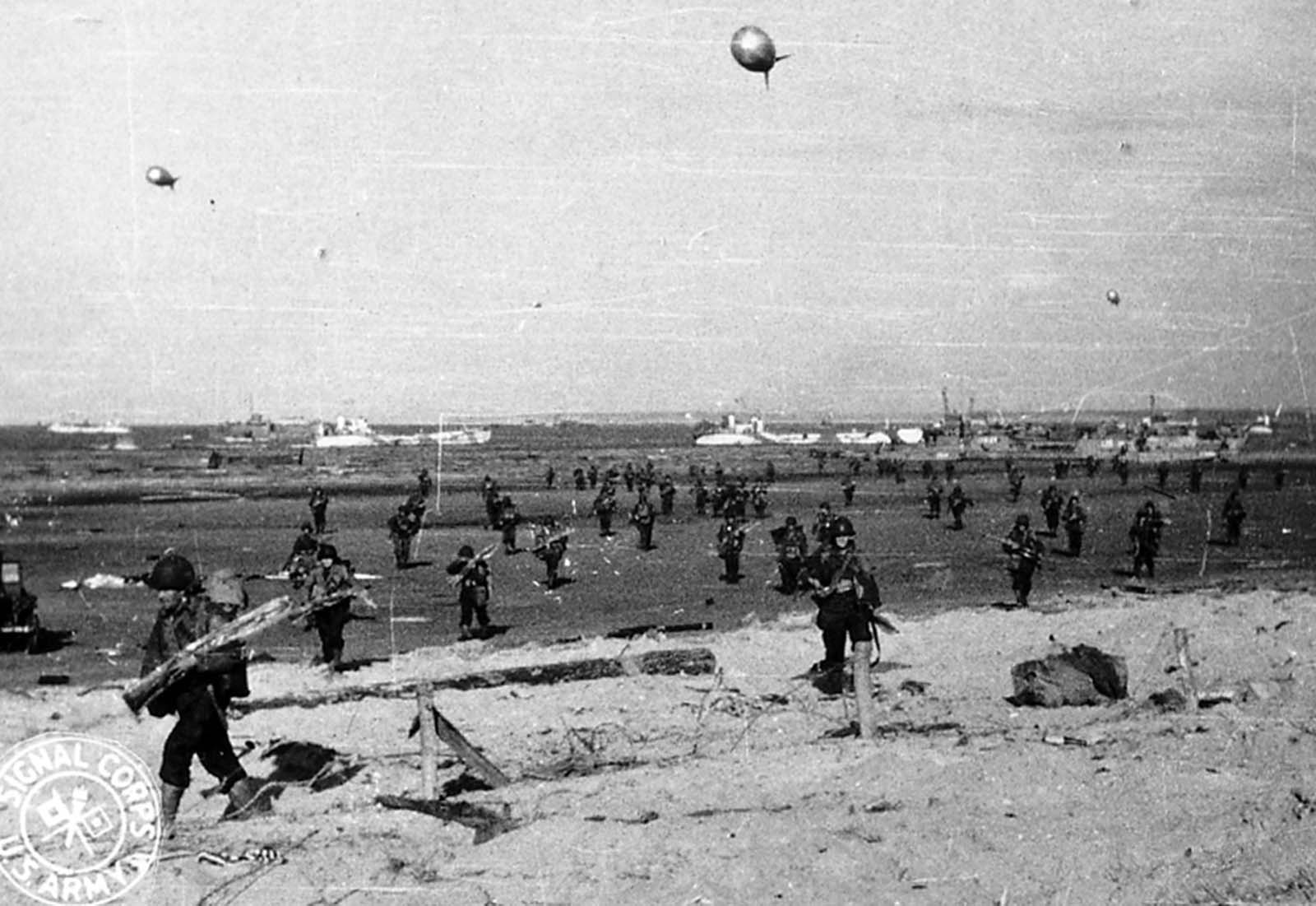

The military term “D-Day” refers to the day when a combat operation is to start, and “H-hour” is the exact time the operation commences. This concept permits military strategists to plan for an operation in advance, even when the exact date and time of the action are still unknown. D-Day will, however, be associated with the invasion of Normandy, one of the largest and the most famous amphibious operations in the history of war. As the D-Day grows more distant in the mirror of history, the pictures remain with us, almost an uncompromising keepsake to that extraordinary, remarkable event. Each photograph conveys only a single moment in time, a second of experience, a glimpse into the reality of the instant. These unforgettable photographs show us the uniforms, the weapons, the equipment, the preparations, the setting, the sufferings, the heroism, and the bravery that took place on June 6, 1944. The war in Europe had raged since the German Invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, and the United States joined the struggle against the Axis powers on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. During the years leading up to the Allies’ cross-Channel invasion of the European continent, millions of lives had been lost, and the Allies would accept nothing less than unconditional surrender from Germany and Japan. The third Axis nation, Italy, was invaded on July 9, 1943, and subsequently surrendered on September 8, 1943. After months of preparation, planning, and stockpiling of men, ships, and weapons, the Allies were ready to assault the European continent. From January to May 1944, more than 589,000 men arrived in the United Kingdom in advance of the invasion. The Germans expected the Allies to come ashore at Calais on the French coast, as this is the narrowest point along the Strait of Dover between England and France, and had heavily reinforced the Atlantic seawall with a vast network of shore batteries, beach obstacles, and minefields. The Allies instead chose to invade the European continent along the Normandy region coastline in the Bay of the Seine, roughly between Le Havre in the north and Cherbourg on the Cotentin Peninsula in the south. After months of training soldiers in how to assault the beaches and sailors in how to handle landing craft and larger amphibious ships, a target date was set for Operation Neptune ─ the amphibious assault phase of Operation Overlord (the invasion of France). Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was selected as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force. Managing the naval aspect of the invasion was Adm. Sir Bertram Ramsay (Royal Navy), who served as Supreme Naval Commander for the operation. Tides in the Bay of the Seine where the invasion would take place were very complex. When the tide rises from low to high water, the change in depth can be as much as 5 feet per hour, and the difference in area between high and low tide can cover more than 20 feet. The command created tide tables that contained estimations of the tidal movement, and ranges for each invasion beach. Photo reconnaissance pilots overflow the beaches recording the position of the tides and times of the movements. The tide tables also gave planners a good estimate as to when the German anti-invasion obstacles would be covered by the sea and to what depth, or when they would be exposed and easy for the landing craft to avoid. However, landing on the beach at low tide would expose the invading troops to great fire from the defenders. Whatever path was chosen, men would be put into harm’s way. The invasion troops were boarded on ships at every dock, beach, and pier in Southern England on May 28. US forces were supported by and transported in 931 ships, while the British and Commonwealth Armies sailed in 1,796 ships of all types. The invasion ships were ready on June 3, but the weather was not cooperating. June 4 was no better, and June 5 was predicted to be miserable too. Forecasters predicted a break in the weather on June 6, and close to midnight on June 4, General Eisenhower gave the invasion order: D-Day was set for the morning of June 6. The invasion armada sortied from the coast of England on the morning of June 5. During the early-morning hours of June 6, more than 13,000 American and 8,500 British paratroopers landed behind the beaches. They were to capture vital bridges and secure beach exits to enable soldiers of the seaborne assault to move inland as quickly as possible. Offshore, at 2:00 a.m., minesweepers moved in, clearing channels for the fire support and amphibious ships that were soon to follow. At 6:00 a.m., as ships of the invasion fleet approached the landing areas, German heavy coastal batteries opened up, firing at the approaching invasion fleet. Facing the soldiers coming ashore were beach obstacles designed to snare landing craft, anti-ship mines, anti-personnel mines along the beaches and down to the tide line, one armored division, two mobile infantry divisions, and three additional divisions of vehicle-less infantry. Six armored divisions plus the German Fifteenth Army were within the day’s march of reinforcing the army at the beachhead. Allied troops began reaching the beach at 6:30 a.m. to face withering fire from the German defenders. LCI-93, LCI-553, and LCT-612 were shelled by shore batteries and subsequently sank. The quit weapon ─ undersea mines ─ took a heavy toll; Destroyer Corry (DD-463), anti-submarine patrol craft PC-1261, eleven tank landing craft, and five infantry landing craft were quickly sent to the bottom. Casualties from these ships were enormous, and those who survived had a long swim to the beach, if they could shed their full combat gear, or hoped for rescue by surrounding vessels. In spite of German resistance, both active and passive, more than 21,000 men and more than 1,700 tanks, half-tracks, trucks, and jeeps were ashore Utah Beach by 6:00 p.m. German casemated gun emplacements were the target of the day for the Allied fire-support ships. Gunfire support was called for by Army units on the ground, and the fall of the shot was monitored by Navy pilots flying from land bases in Britain. American troops faced stiffer resistance and increased German fortifications at Omaha Beach. Troops here endured a long trip over open sand, liberally sown with anti-personnel mines, to a concrete seawall topped with barbed wire. To afford the soldiers tactical surprise, the Normandy beaches did not receive any pre-invasion bombardment, either by air or ship, in the weeks prior to the assault. All the German defenses were intact. On the morning of D-Day, shore bombardment by the destroyers, cruisers, and battleships of the invasion fleet turned the tide of battle at Omaha beach. Firing on targets, often within yards of American troops, many of the destroyers closed to within 800 yards of the beach – frequently touching the bottom. As the troops moved away from the beaches, gunfire support ships were hitting targets as far as 10 miles inland. The Allied armies ashore consolidated their position and soon began moving across the French countryside. The Luftwaffe moved aircraft from Italy and Germany to counter the invasion fleet. They used radio-guided bombs, employed with success off the coast of Italy, but Allied air superiority over the French coast limited their effectiveness. German undersea mines continued to extract a high toll for sailing in French coastal waters, sinking or heavily damaging a number of ships before the area was cleared. Operation Neptune was concluded on June 25 when US Navy battleships disabled the Fermanville battery (known to the Germans as the Hamburg battery), part of the coastal defense network surrounding the city of Cherbourg. The Fermanville battery’s four 280mm cannon, with a range of 36 km, harassed Allied shipping until battleships Texas and Arkansas began to slug it out with the German battery. One cannon was put out of action before the Navy declared the duel a draw. Cherbourg fell on June 26 and, after small pockets of resistance were mopped up, the Cotentin Peninsula came completely under Allied control. The Fermanville battery fell on June 28. From Normandy, the land battle began working its way across France, with the Germans fighting to hold every yard of ground. Eleven hard-fought months later, the Allies accepted the unconditional surrender of the Germans on May 7, 1945. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel on D-Day, with 875,000 men disembarking by the end of June. Allied casualties on the first day were at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead. The Germans lost 1,000 men. The five beachheads were not connected until 12 June, by which time the Allies held a front around 97 kilometers (60 mi) long and 24 kilometers (15 mi) deep. Caen, a major objective, was still in German hands at the end of D-Day and would not be completely captured until 21 July. The Allied victory in Normandy stemmed from several factors. German preparations along the Atlantic Wall were only partially finished; shortly before D-Day Rommel reported that construction was only 18 percent complete in some areas as resources were diverted elsewhere. The deceptions undertaken in Operation Fortitude were successful, leaving the Germans obliged to defend a huge stretch of coastline. The Allies achieved and maintained air supremacy, which meant that the Germans were unable to make observations of the preparations underway in Britain and were unable to interfere via bomber attacks. Infrastructure for transport in France was severely disrupted by Allied bombers and the French Resistance, making it difficult for the Germans to bring up reinforcements and supplies. Indecisiveness and an overly complicated command structure on the part of the German high command were also factors in the Allied success. (Photo credit: Regional Council of Basse-Normandie / U.S. National Archives / Library of Congress / US Army Archives / Article based on D-Day The Air and Sea Invasion of Normandy in Photos by Nicholas A. Veronico). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe