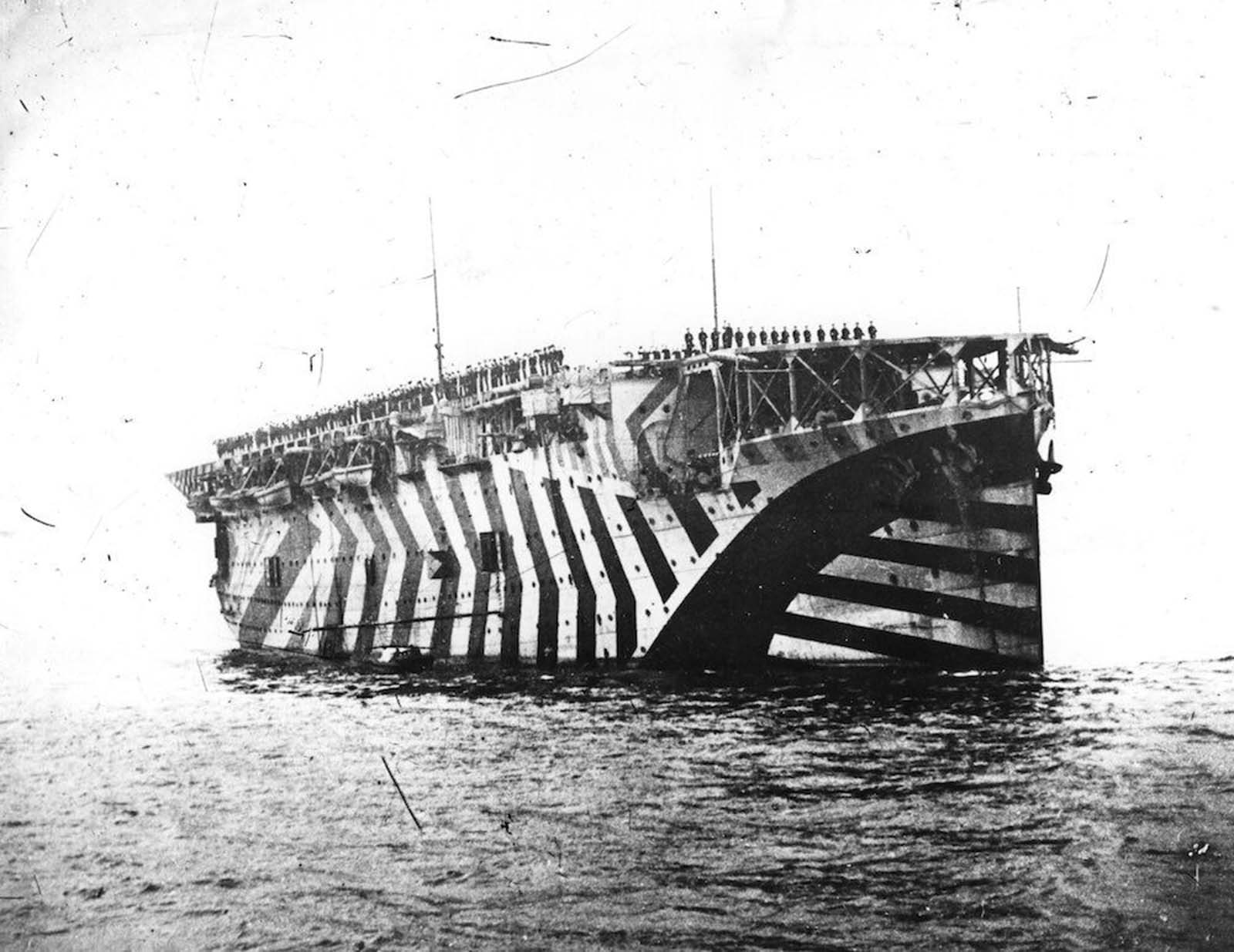

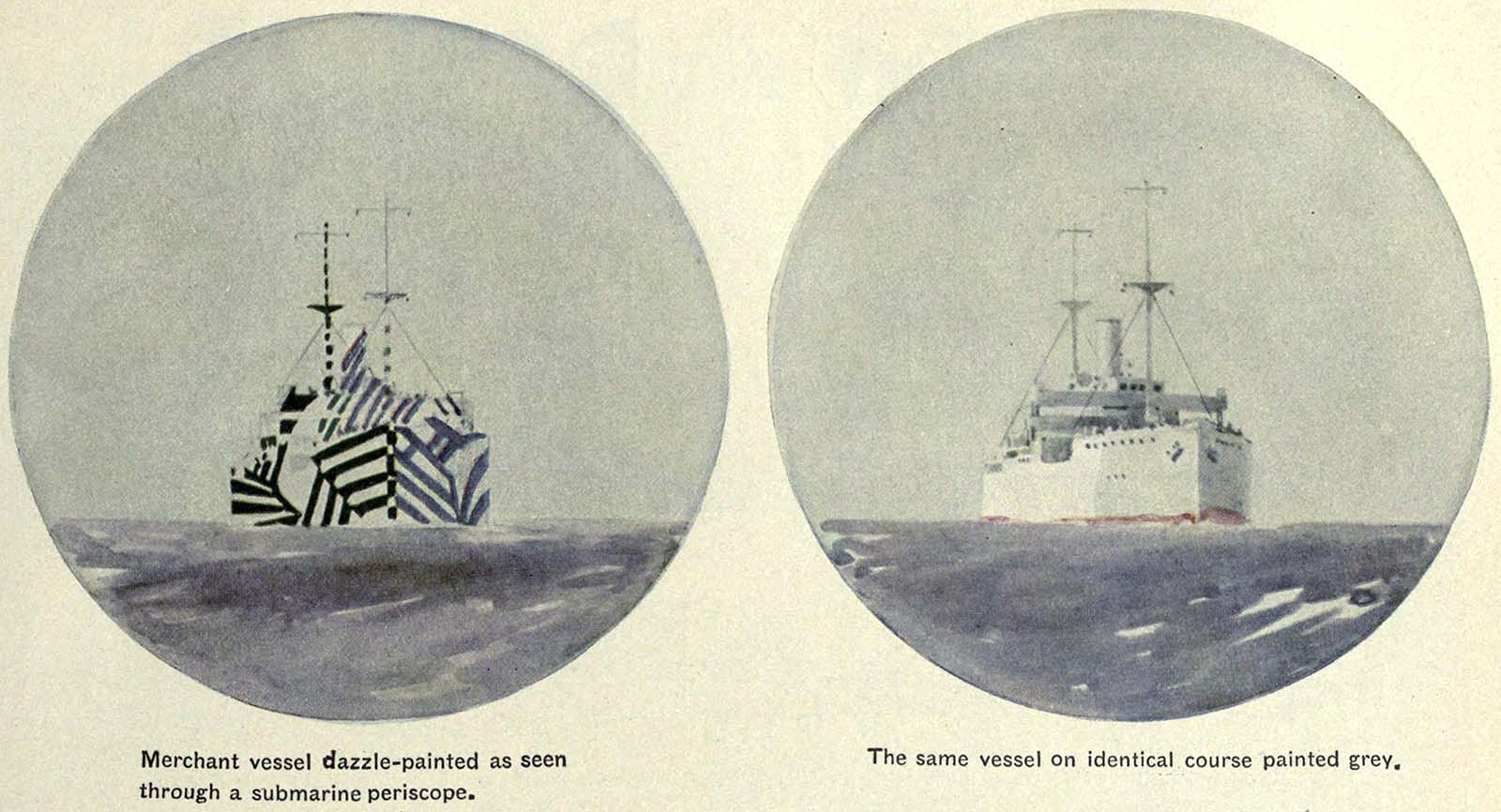

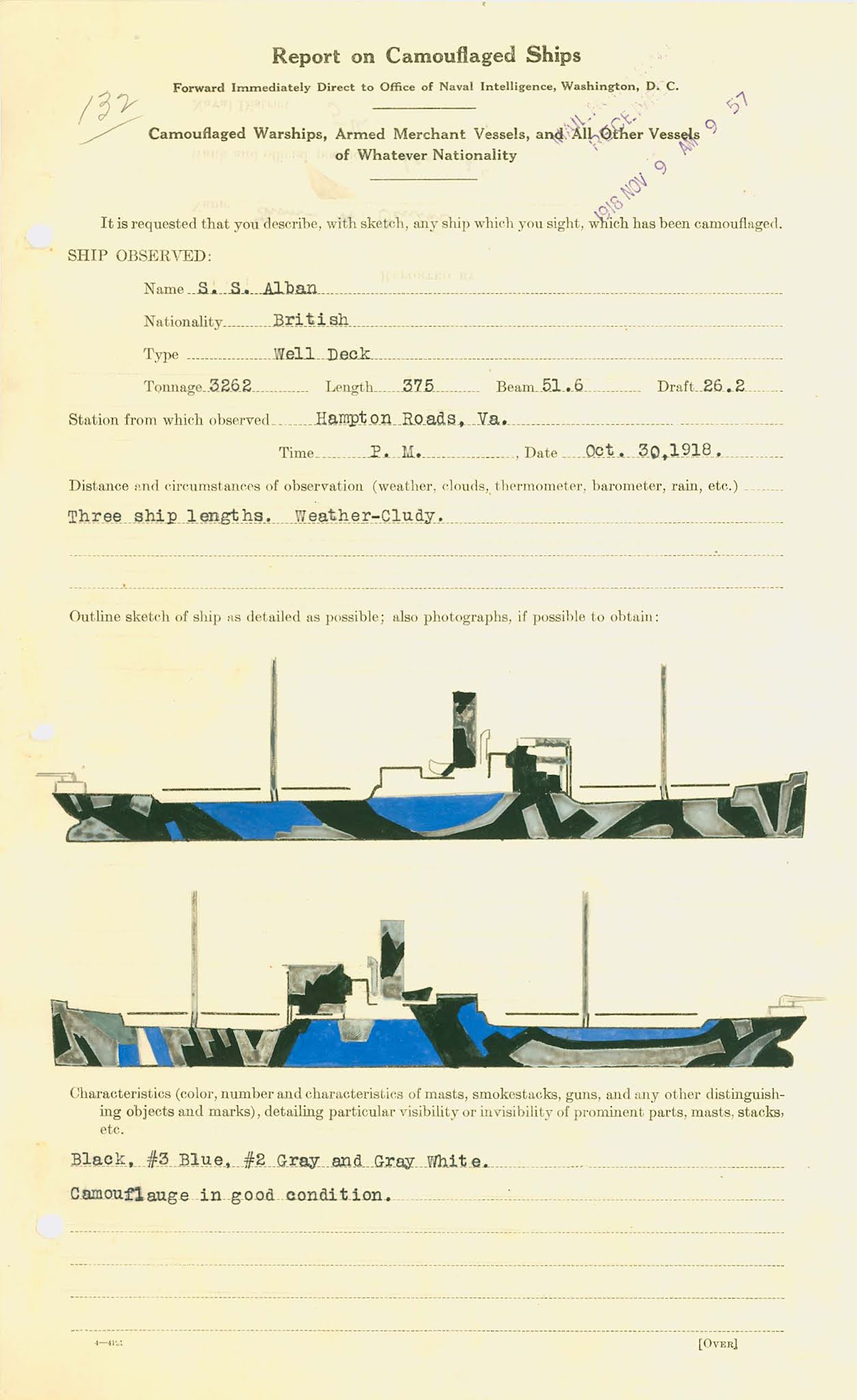

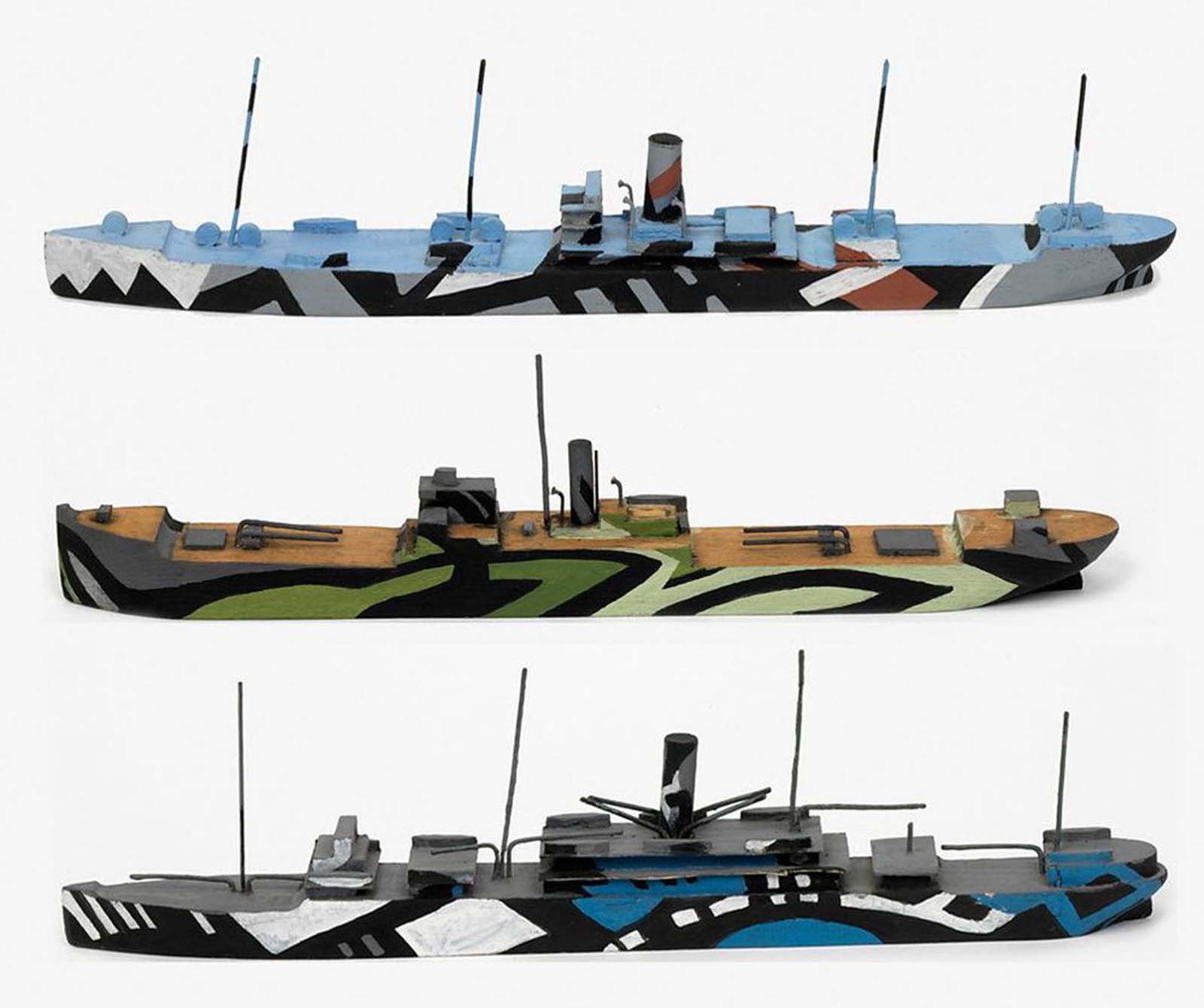

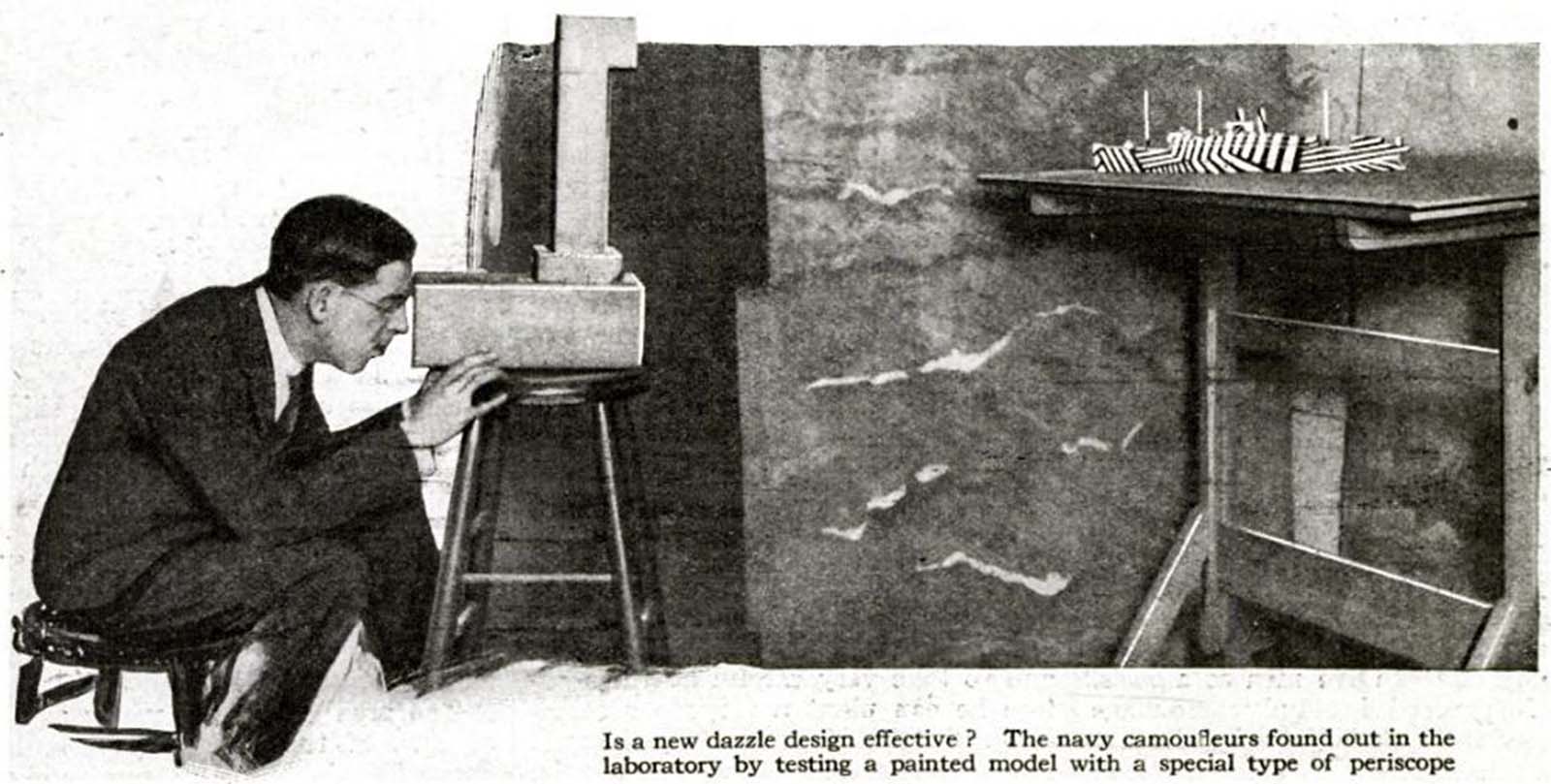

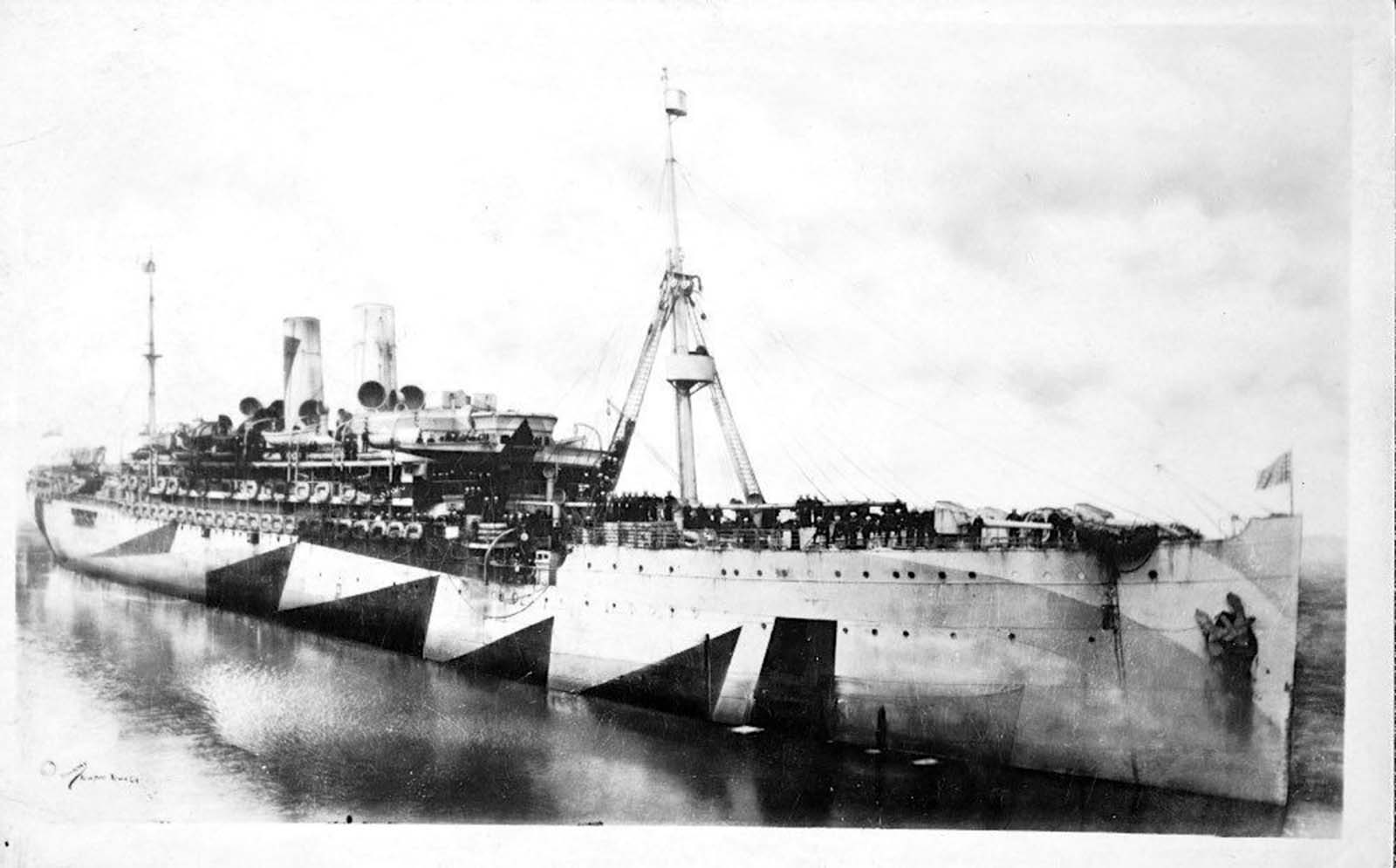

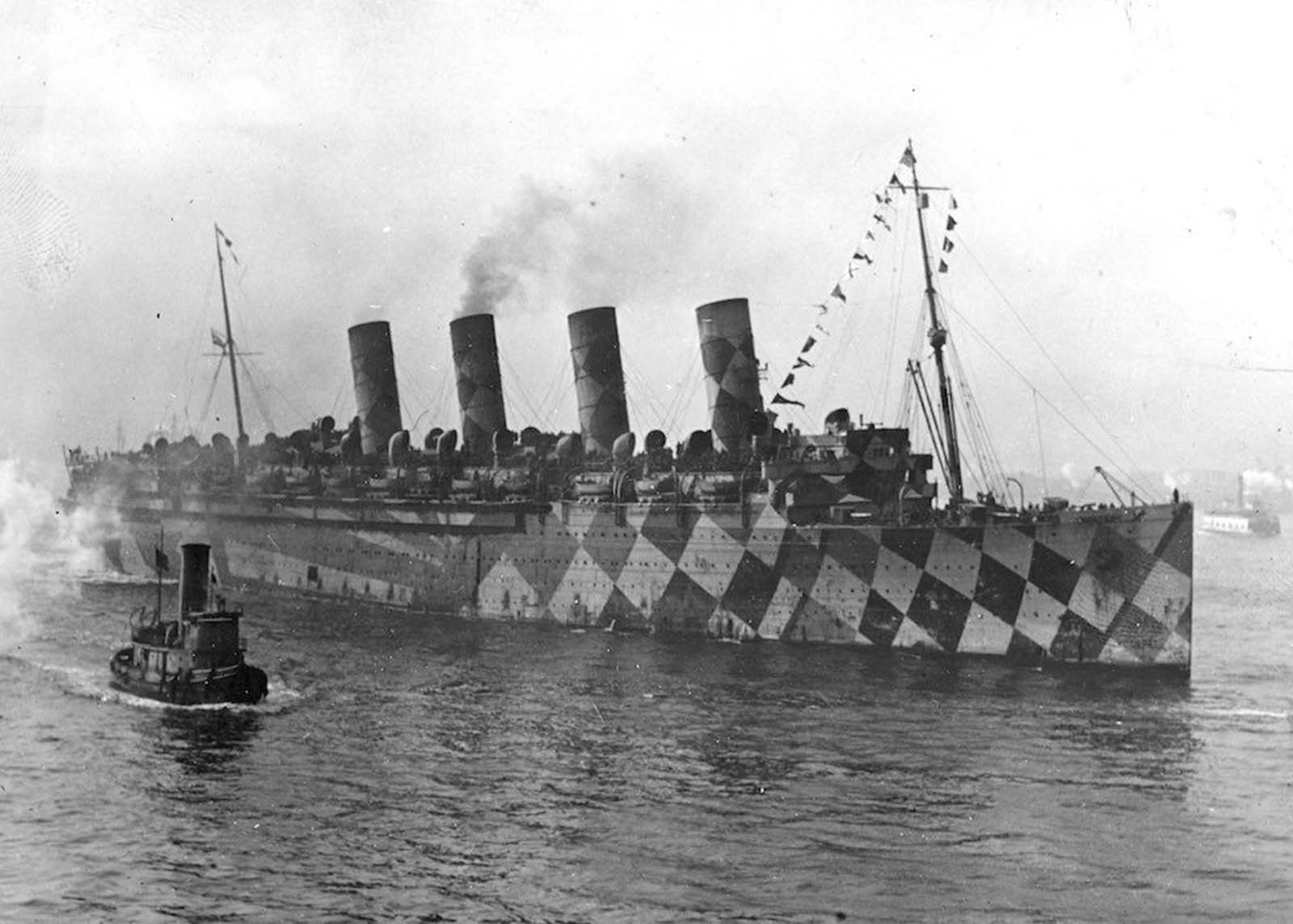

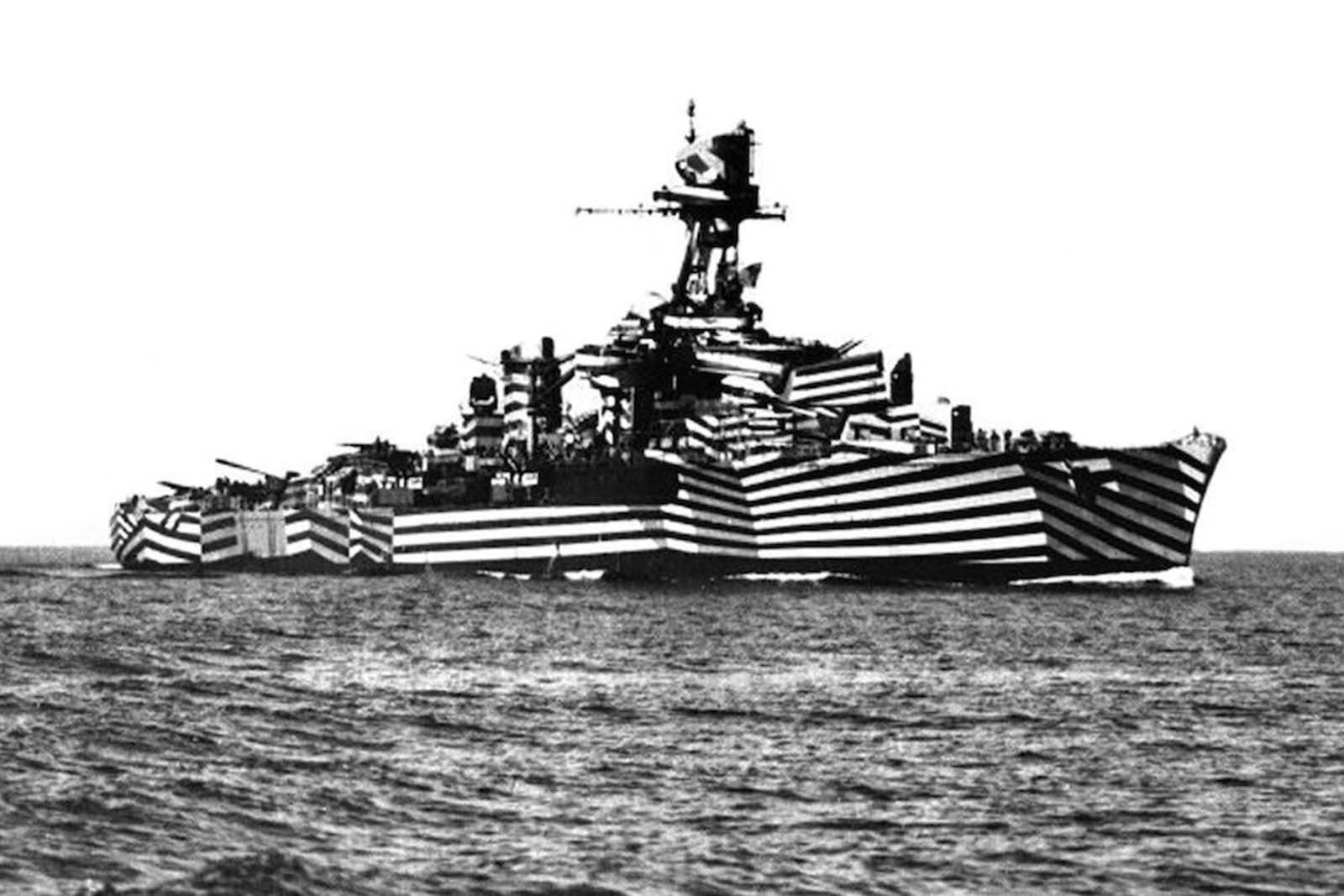

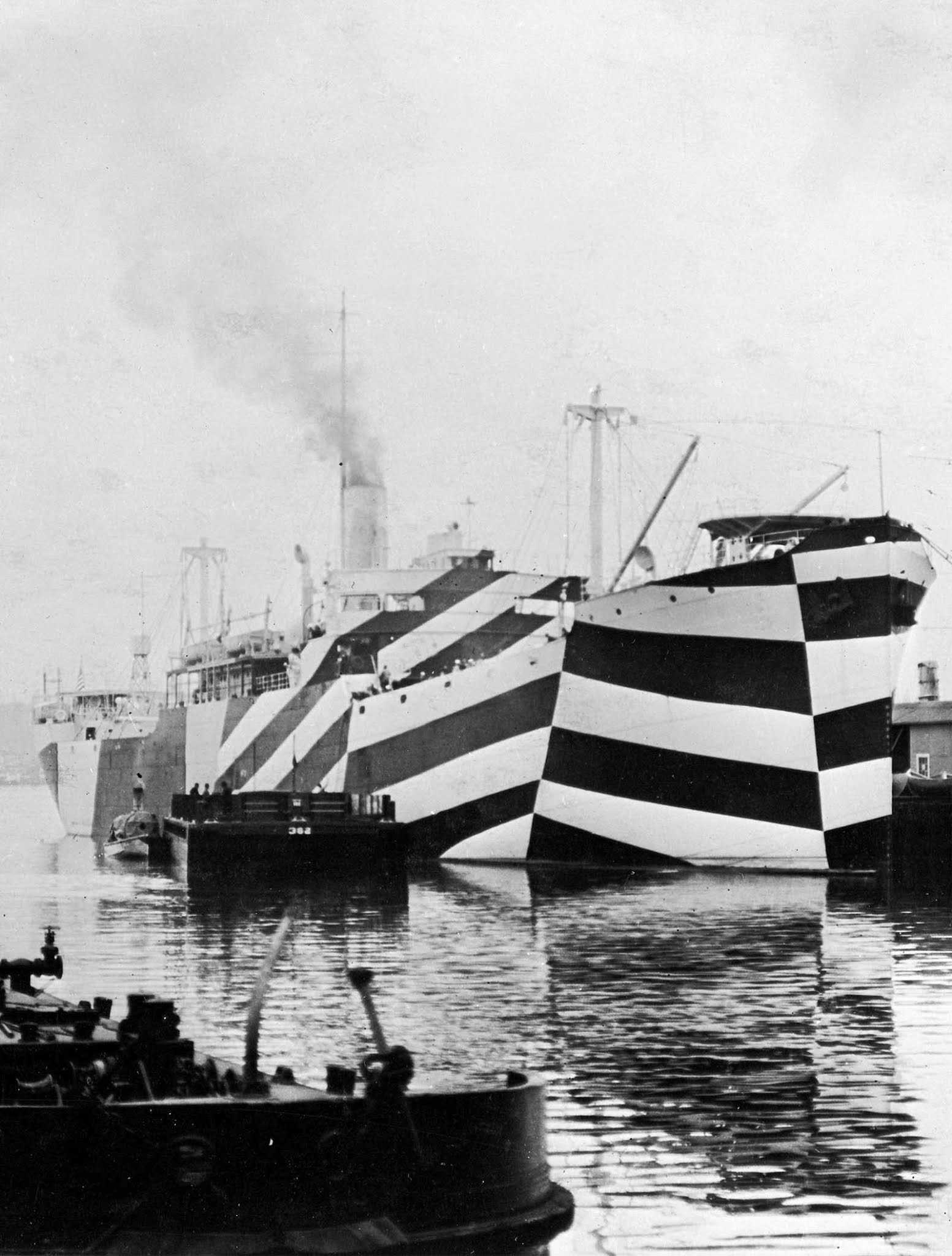

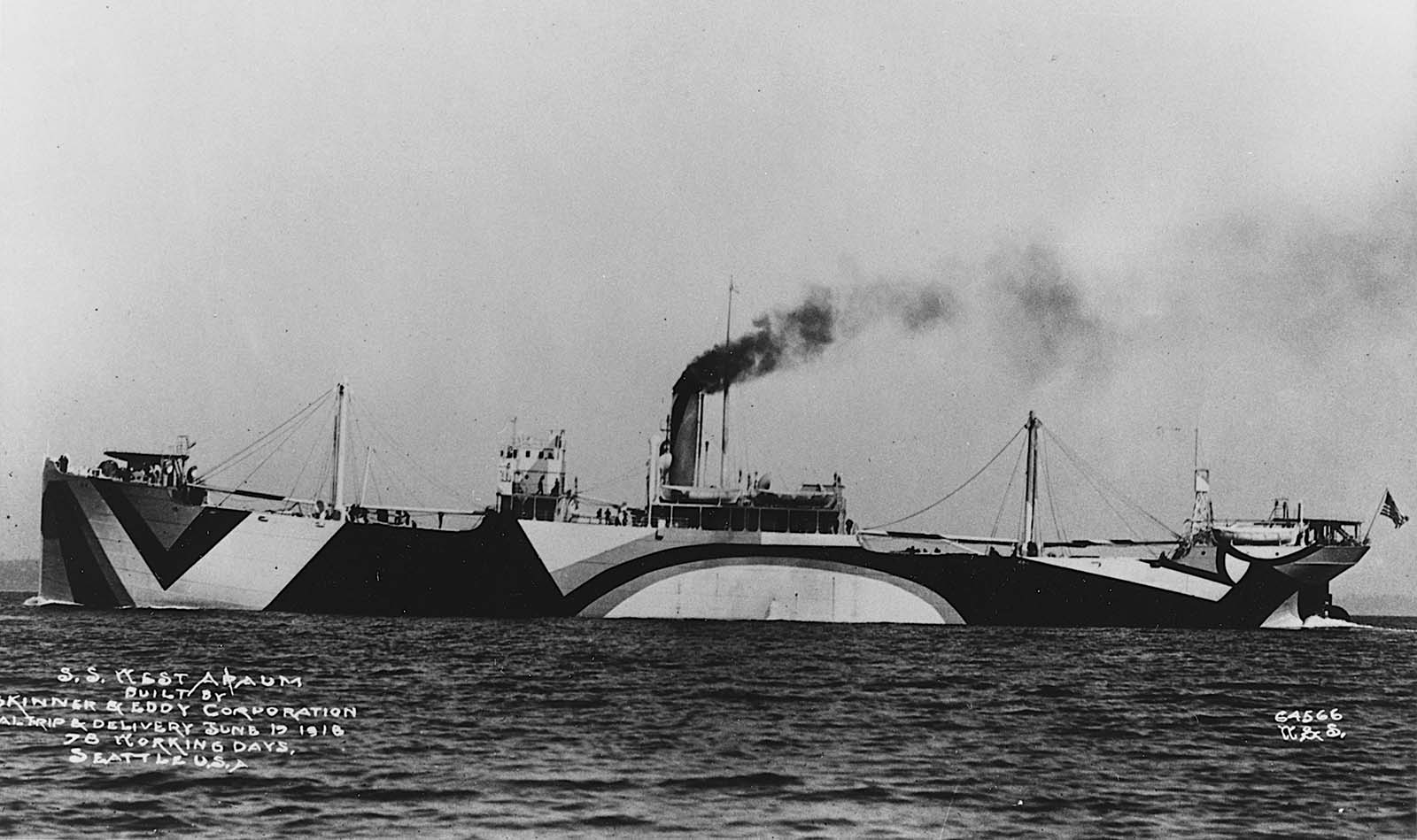

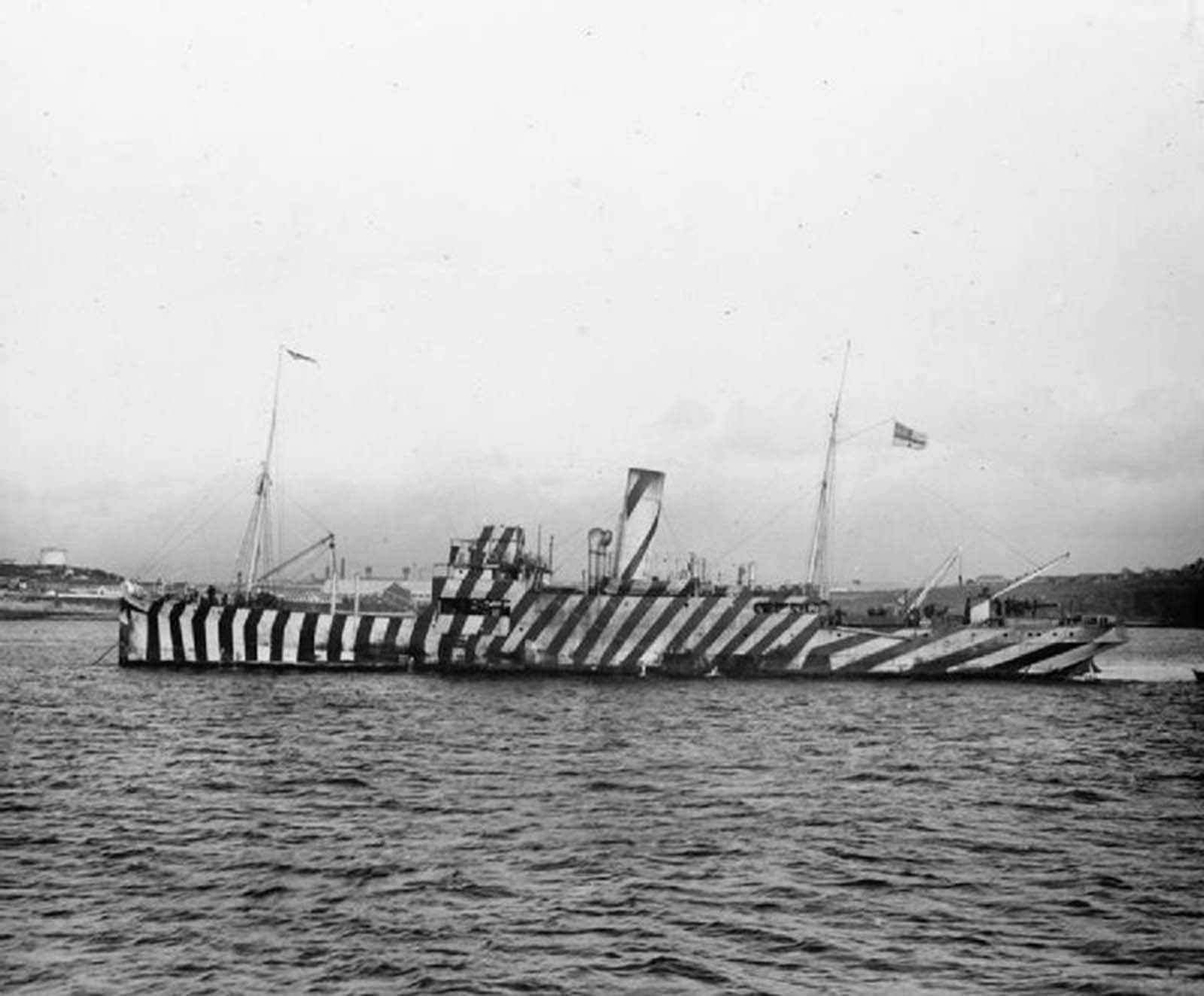

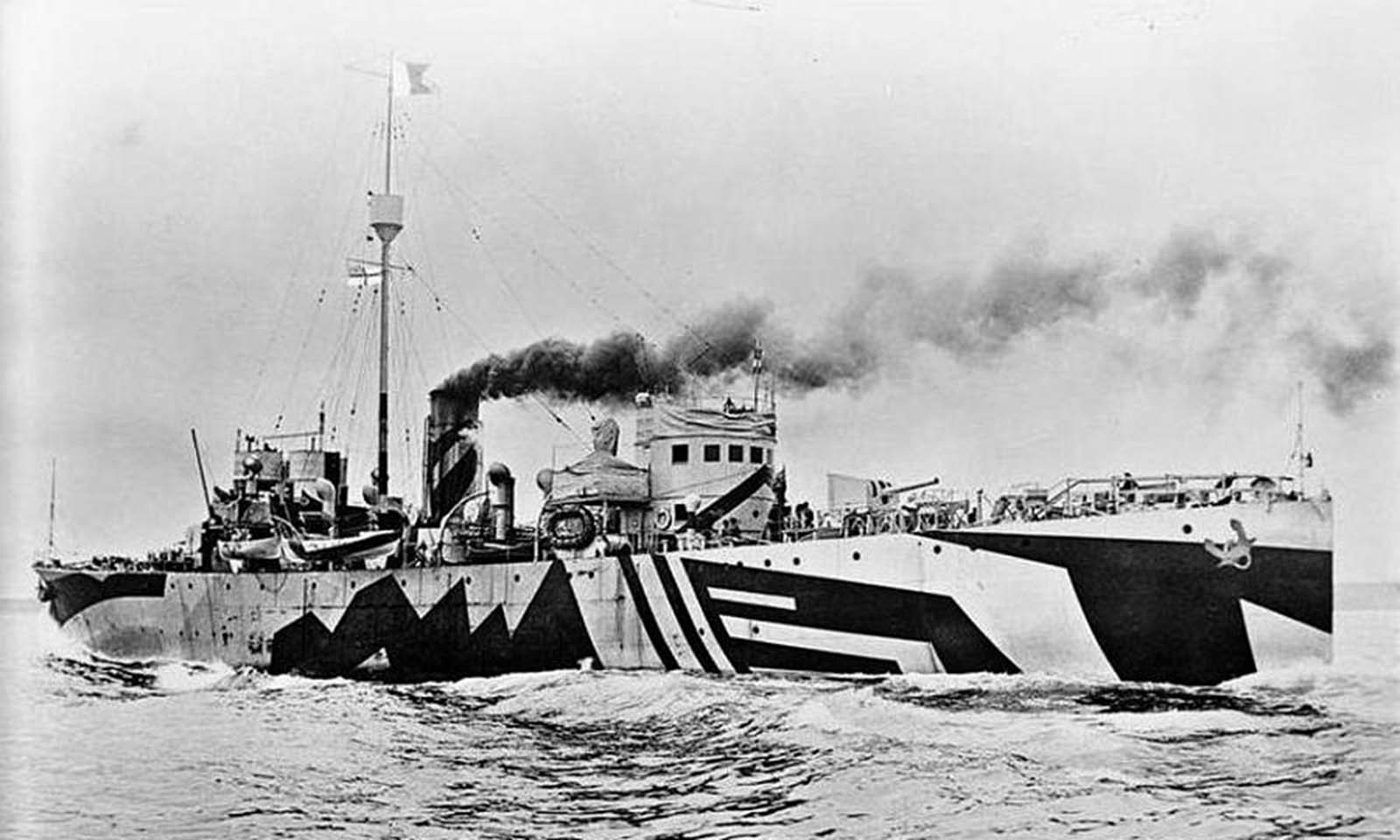

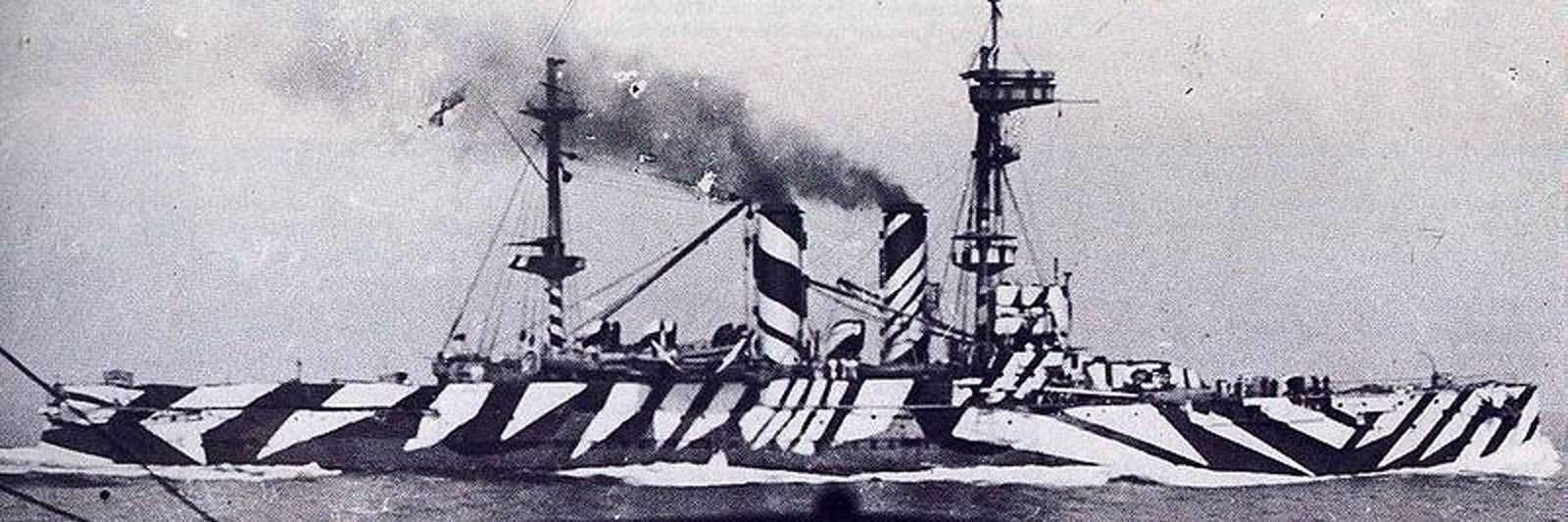

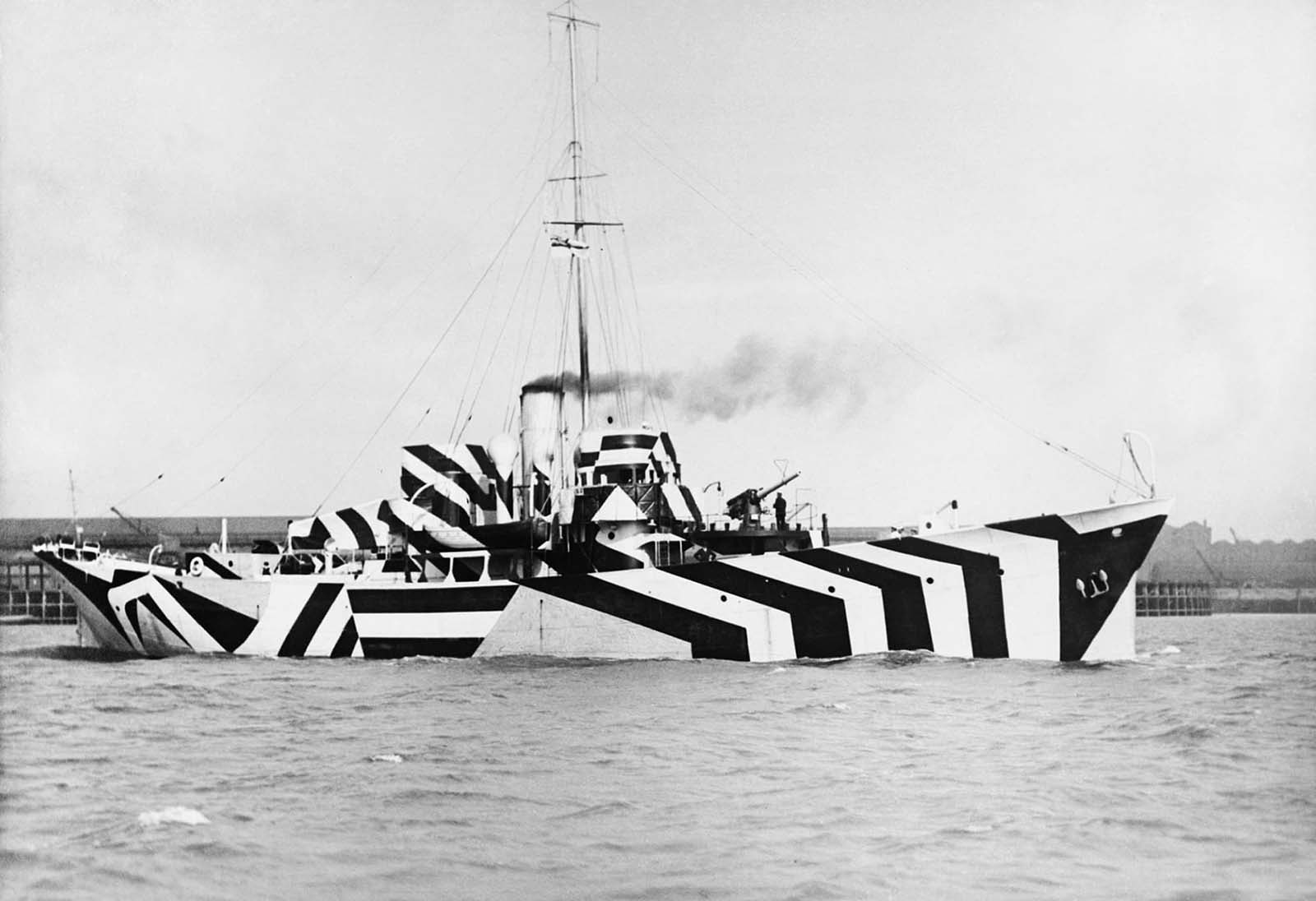

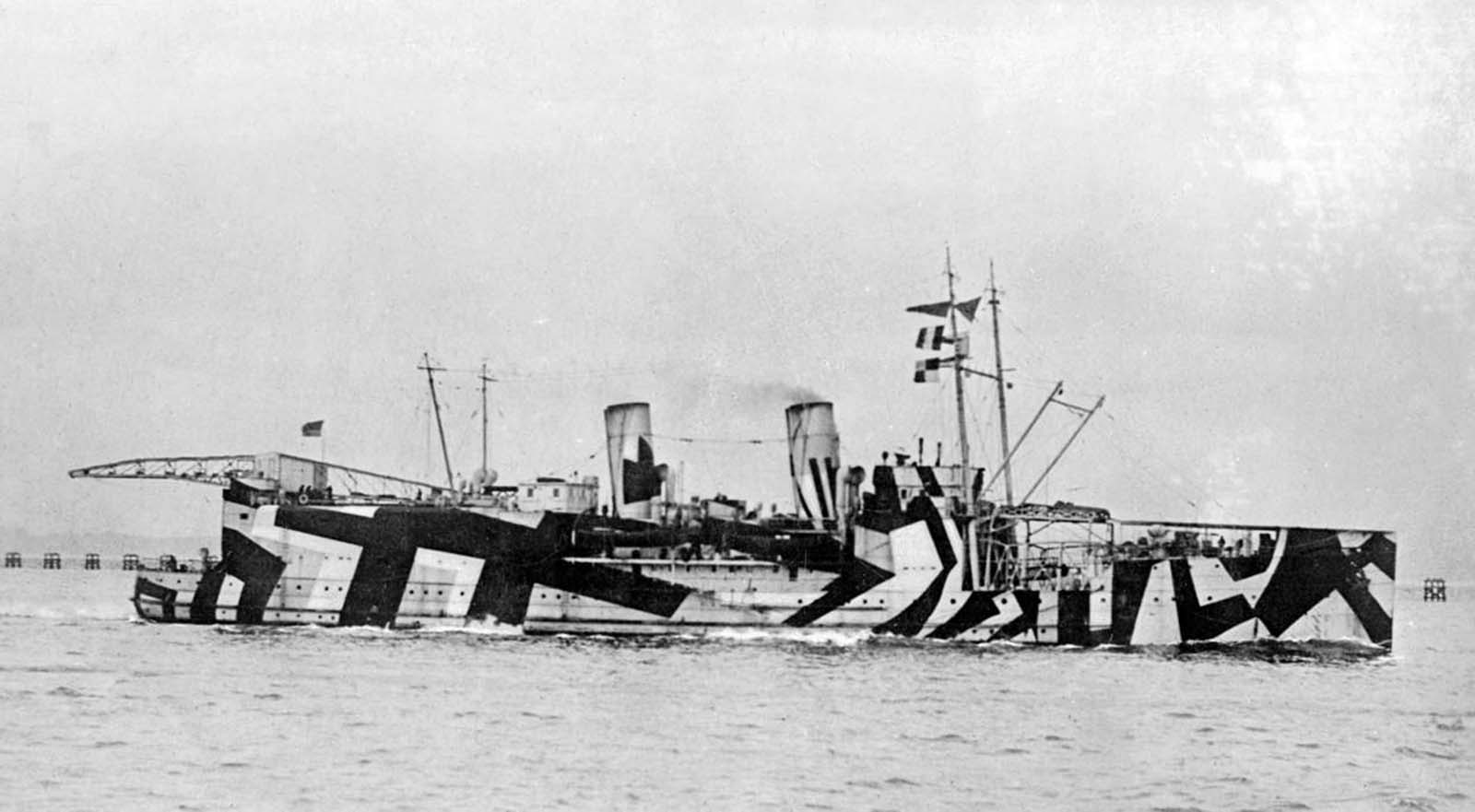

Dazzle camouflage (also known as Razzle Dazzle or Dazzle painting) was a military camouflage paint scheme used on ships, extensively during World War I and to a lesser extent in World War II. The idea is credited to the British artist Norman Wilkinson who came with this idea in 1917, a time when German U-Boat attacks on British ships seemed unstoppable. Norman Wilkinson recalls: “I suddenly got the idea that since it was impossible to paint a ship so that she could not be seen by a submarine, the extreme opposite was the answer — in other words to paint her, not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading.” Thus “dazzle” camouflage — bold stripes, curves, and zig-zags in colors like black, white, blue, fuchsia, and green — was born. The design consists of complex patterns of geometric shapes in contrasting colours, interrupting and intersecting each other. Unlike other forms of camouflage, the intention of dazzle is not to conceal but to make it difficult to estimate a target’s range, speed, and heading. Norman Wilkinson explained in 1919 that he had intended dazzle primarily to mislead the enemy about a ship’s course and so cause them to take up a poor firing position. In other words, Wilkinson’s idea was to “dazzle” the gunner so that he would either be unable to take the shot with any confidence or spoil it if he did. The shot had to only be 8 to 10 degrees off for the torpedo to miss. And even if the ship was hot, if the torpedo didn’t hit the most vital part, that would be better than being hit directly. Curves painted across the side of the ship could create a false bow wave, for example, making the ship seem smaller or imply that it was heading in a different direction: Patterns disrupting the line of the bow or stern made it hard to tell which was the front or back, where the ship actually ended, or even whether it was one vessel or two; and angled stripes on the smokestacks could make the ship seem as if it was facing in the opposite direction. The system did have its limitations – it could only be applied to ships that would be targeted by periscopes, because it worked best when seen from the low-down viewpoint of a U-boat gunner. The first ship to be dazzled was a small store ship called the HMS Industry; when it was launched in May 1917, coastguards and other ships sailing the British coast were asked to report their observations of the vessel when they encountered it. Enough observers were sufficiently confused that by the beginning of October 1917, the Admiralty asked Wilkinson to dazzle 50 troopships. Wilkinson went to work with a team of 19– five artists, three model makers, and 11 female art students who hand-colored the technical plans for the final designs. Each design not only had to be unique to prevent U-boat crews from getting used to them, but they also had to be tailored to individual ships. Overall, 4000 British merchant ships were painted in what came to be known as “dazzle camouflage”; dazzle was also applied to some 400 naval vessels. Dazzle’s effectiveness was highly uncertain at the time of the First World War, but it was nonetheless adopted both in the UK and North America. In 1918, the Admiralty analyzed shipping losses but was unable to draw clear conclusions. Dazzle ships had been attacked in 1.47% of sailings, compared to 1.12% for uncamouflaged ships, suggesting increased visibility, but as Wilkinson had argued, dazzle was not attempting to make ships hard to see. Suggestively, of the ships that were struck by torpedoes, 43% of the dazzle ships sank, compared to 54% of the uncamouflaged; and similarly, 41% of the dazzle ships were struck amidships, compared to 52% of the uncamouflaged. These comparisons could be taken to imply that submarine commanders did have more difficulty in deciding where a ship was heading and where to aim. Furthermore, the ships painted in dazzle were larger than the uncamouflaged ships, 38% of them being over 5000 tons compared to only 13% of uncamouflaged ships, making comparisons unreliable. The abstract patterns in dazzle camouflage inspired artists including Picasso. With characteristic hyperbole, he claimed credit for camouflage experiments, which seemed to him a quintessentially Cubist technique. In a conversation with Gertrude Stein shortly after he first saw a painted cannon trundling through the streets of Paris he remarked, “Yes it is we who made it, that is cubism”. (Photo credit: Topical Press Agency / Library of Congress / Smithsonian Magazine / Wikimedia Commons). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe