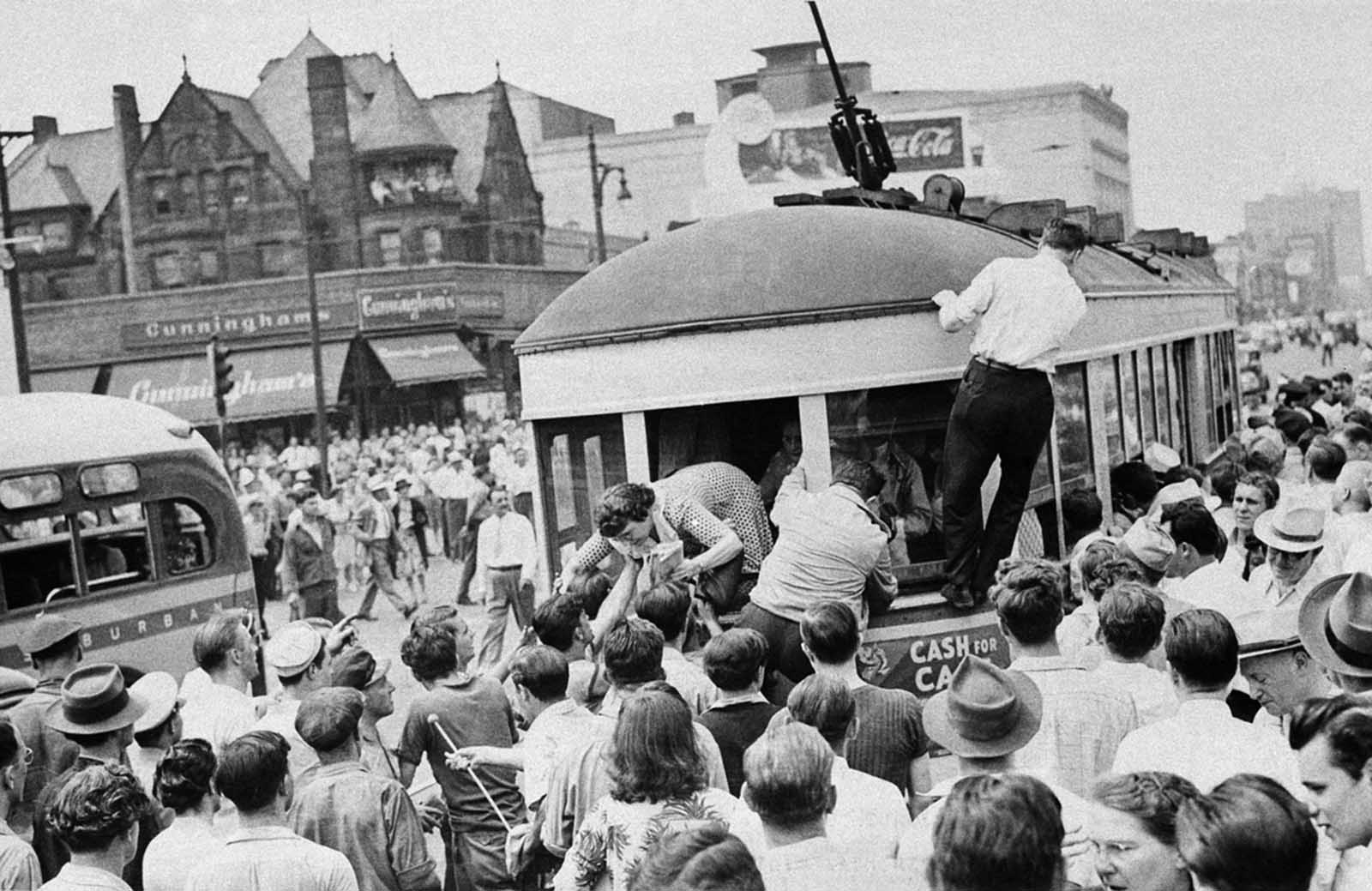

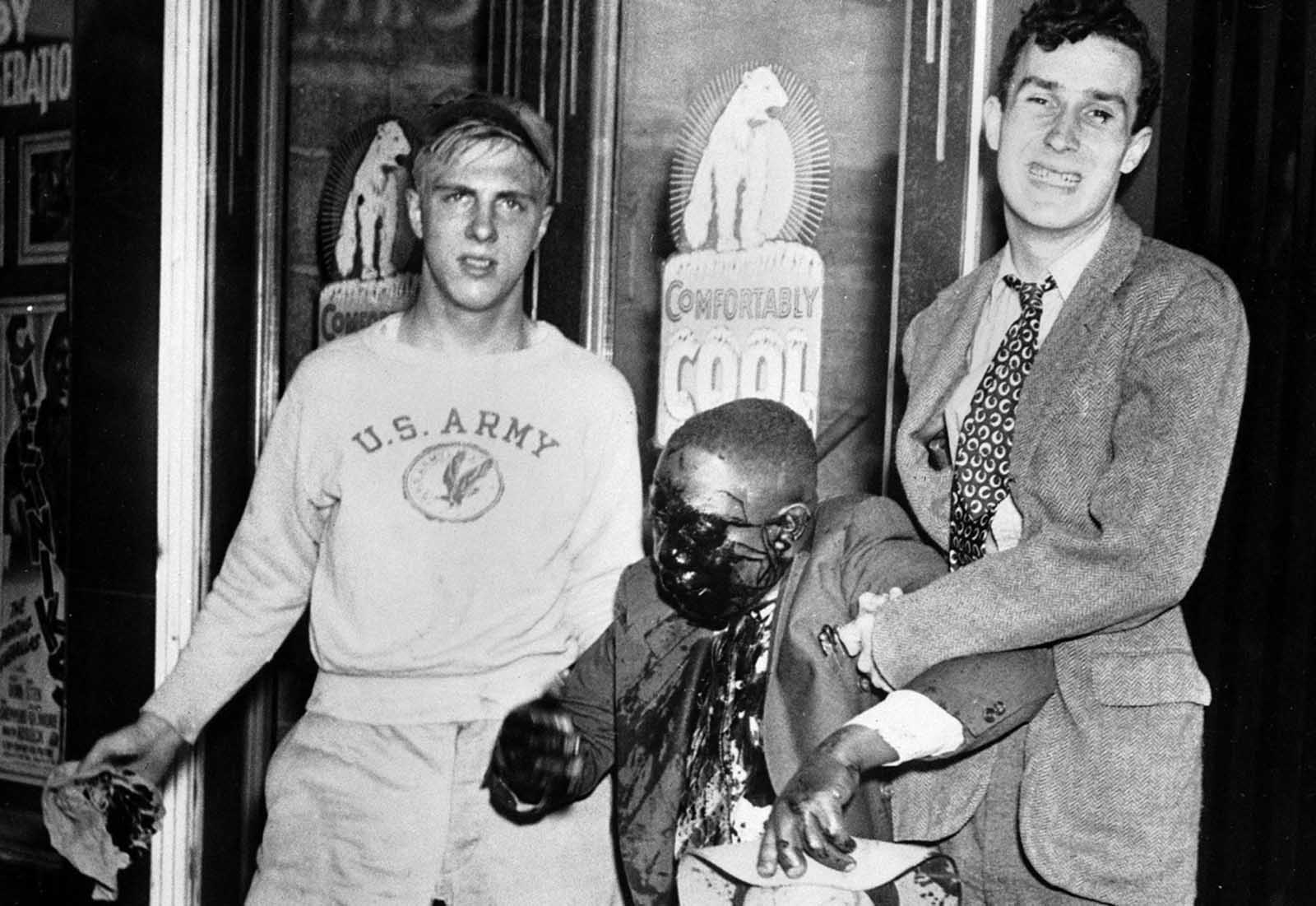

The early part of the 20th century saw the city of Detroit, Michigan, rise to prominence on the huge growth of the auto industry and related manufacturers. The 1940s were boom years of development, but the decade was full of upheaval and change, as factories re-tooled to build war machines, and women started taking on men’s roles in the workplace, as men shipped overseas to fight in World War II. The need for workers brought an influx of African-Americans to Detroit, who met stiff resistance from whites who refused to welcome them into their neighborhoods or work beside them on an assembly line. Sparked by seemingly minor altercations amid aggressive white resistance to black labor flocking to the city’s factories during America’s ramped-up war effort, the Detroit riots (June 20-22) killed 34 people — 25 African Americans, nine whites — wounded hundreds more and damaged and destroyed property worth millions. What’s more, the street violence at home exposed how thin the veneer of “common purpose” truly was across some segments of society, even as Americans were fighting and dying overseas. Just one example of the country’s racially charged hostilities: In the spring of 1943, more than 20,000 white workers at a Detroit plant that produced engines for bombers and PT boats walked off the job in protest over the promotion of a small handful of black workers — a protest hardly emblematic of a nation seamlessly joining together to battle a common enemy. After World War II ended, the demand for workers dried up, and Detroit started plotting its postwar course, an era of big automobiles and bigger highways to accommodate them. At its peak population of 1,849,568, in the 1950 Census, the city was the 5th-largest in the United States, after New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. (Photo credit: Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe