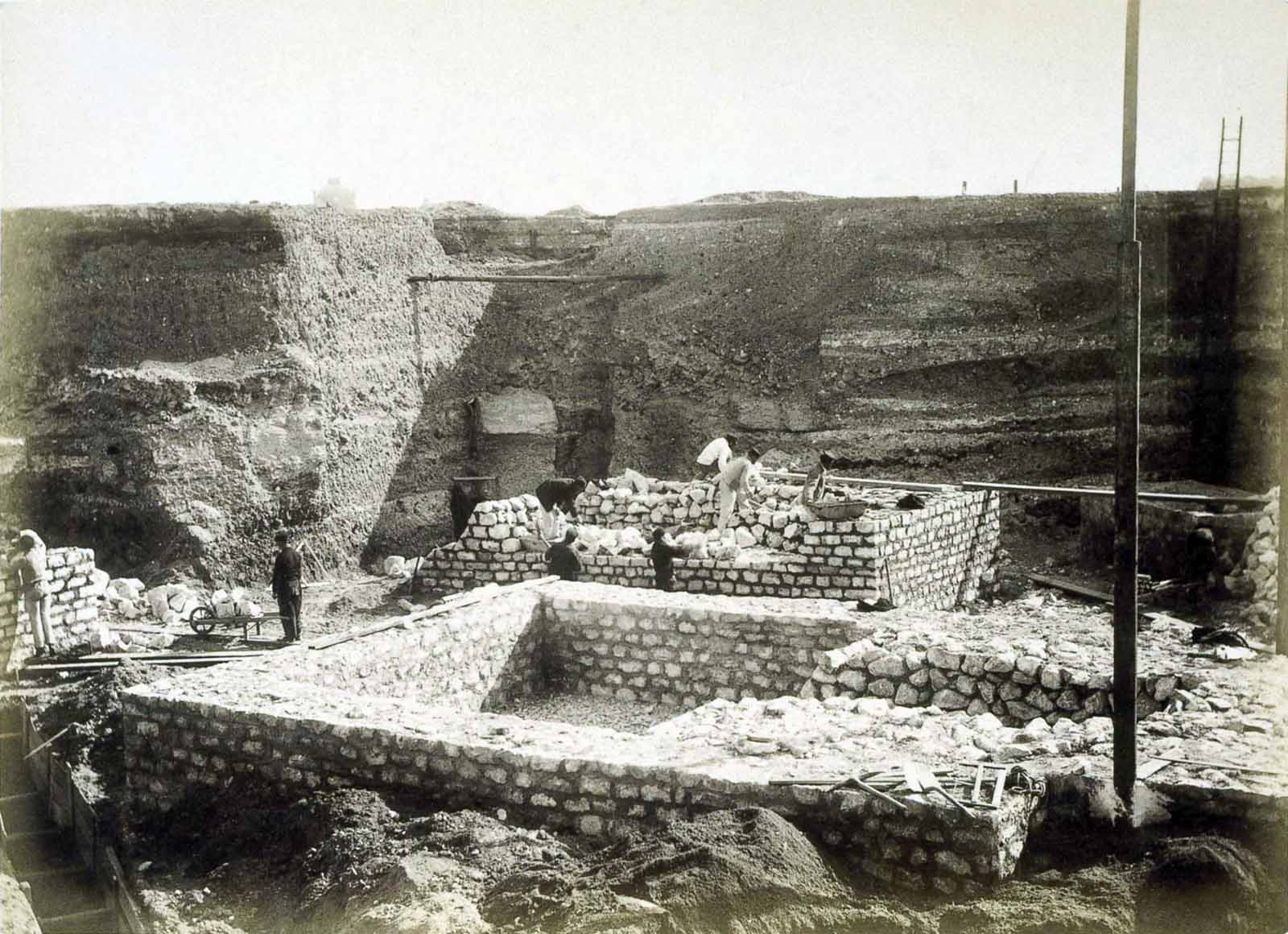

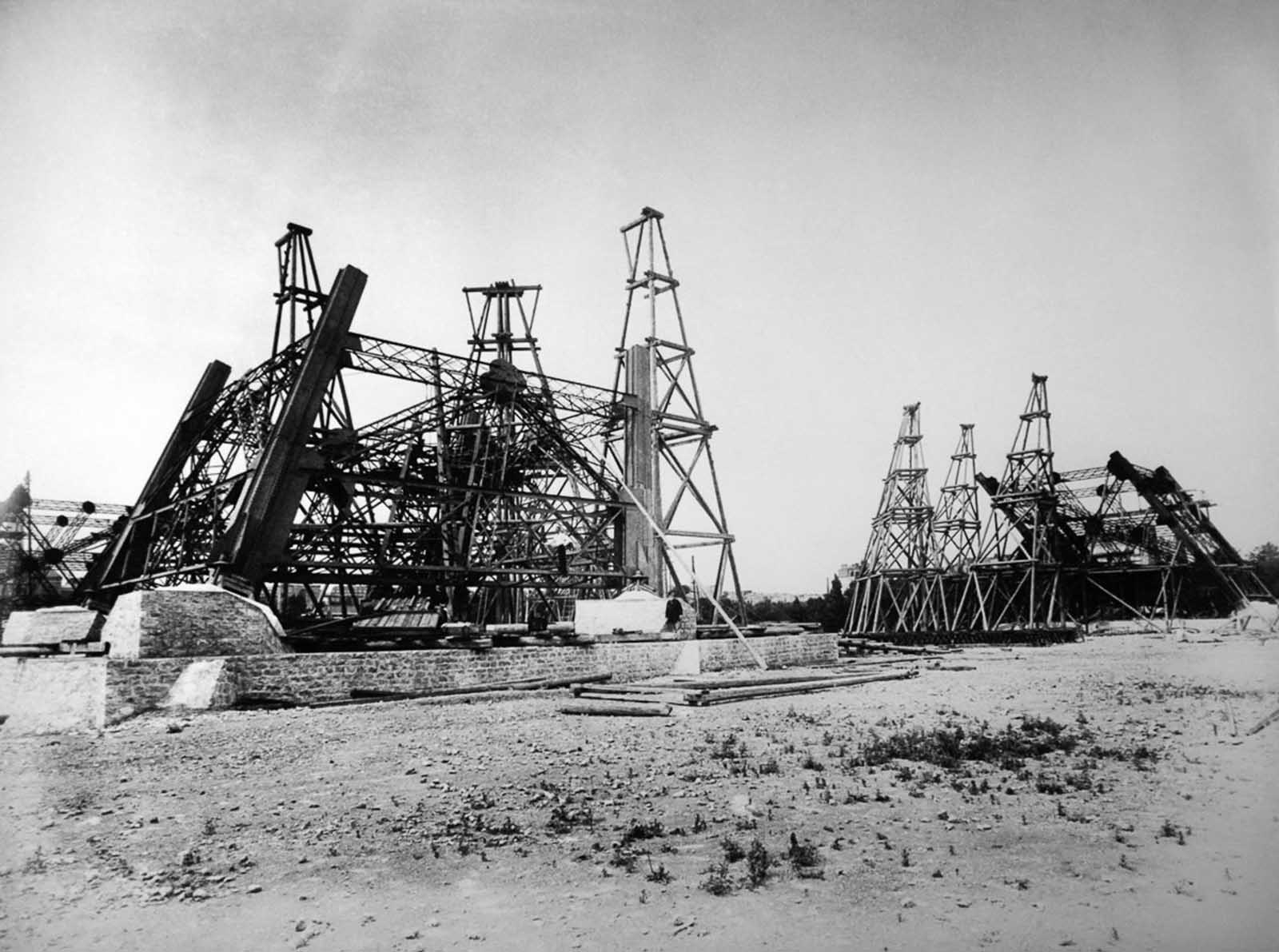

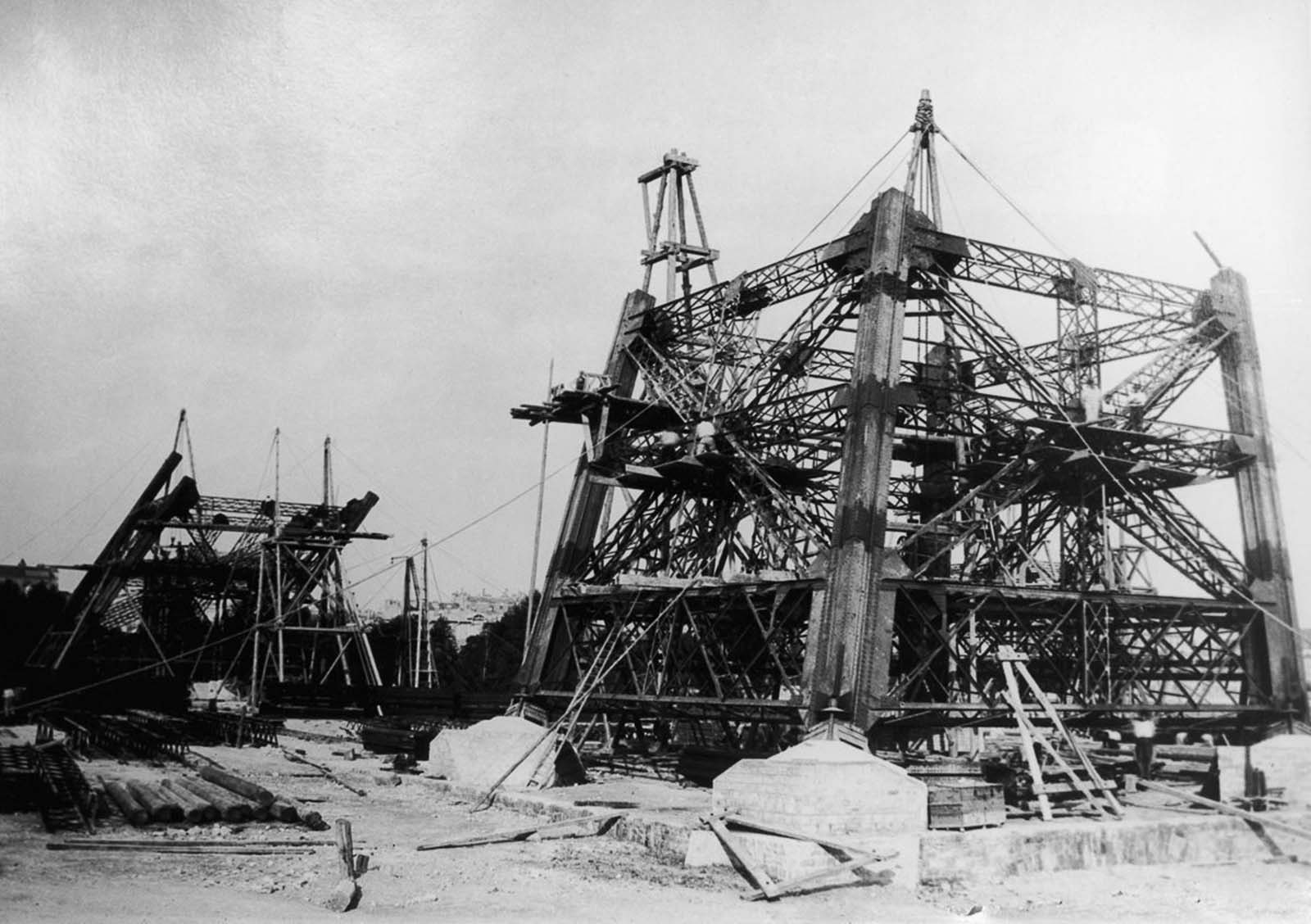

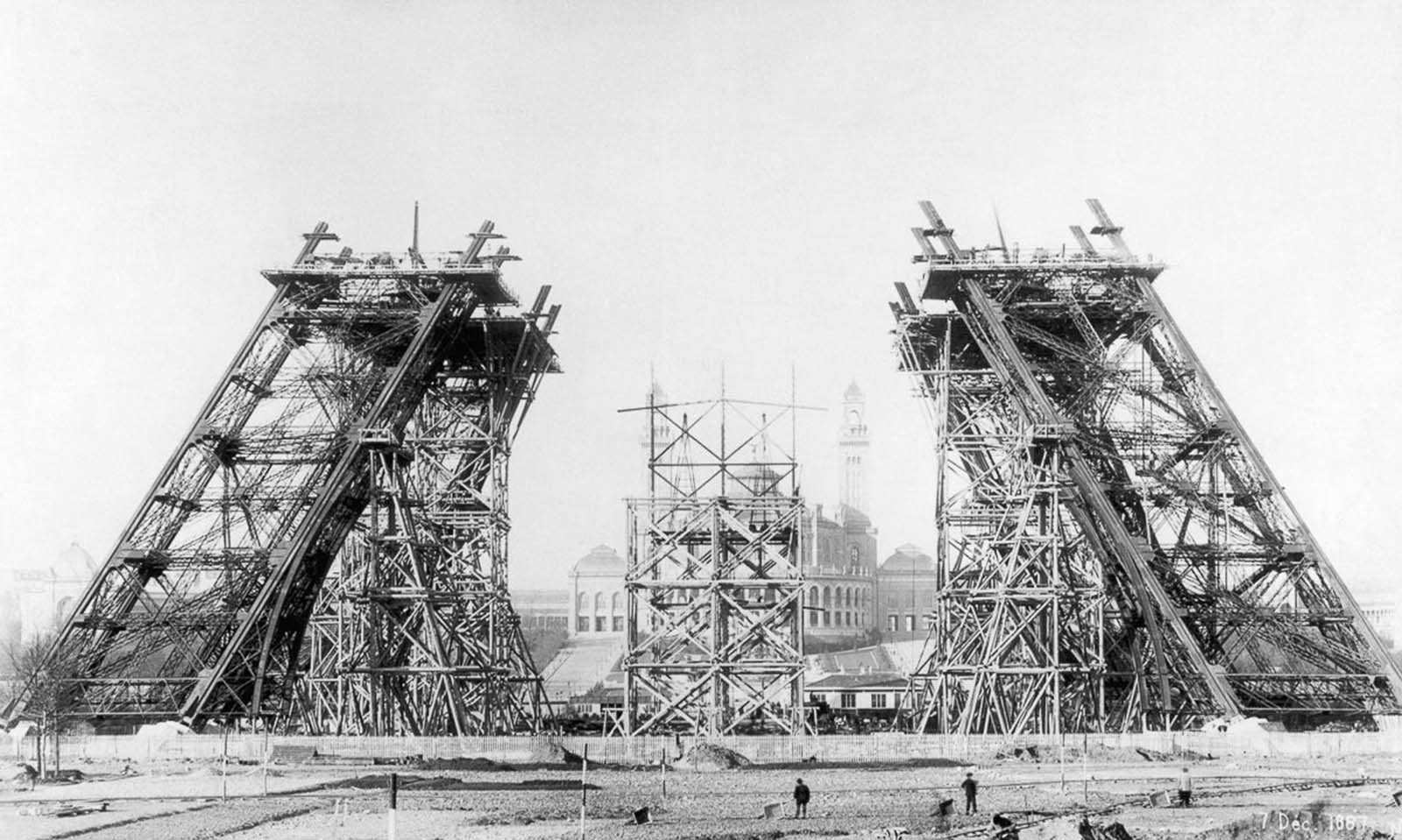

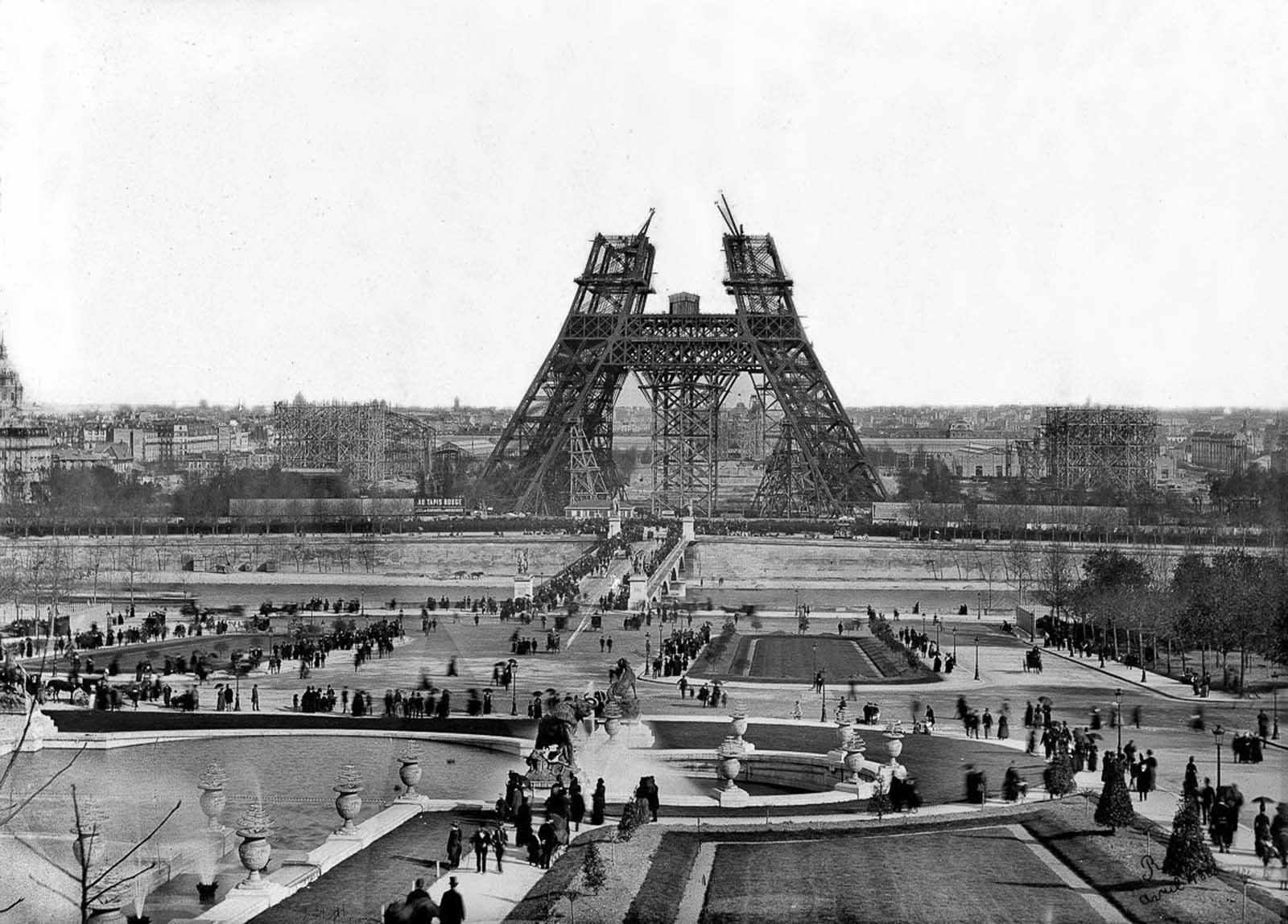

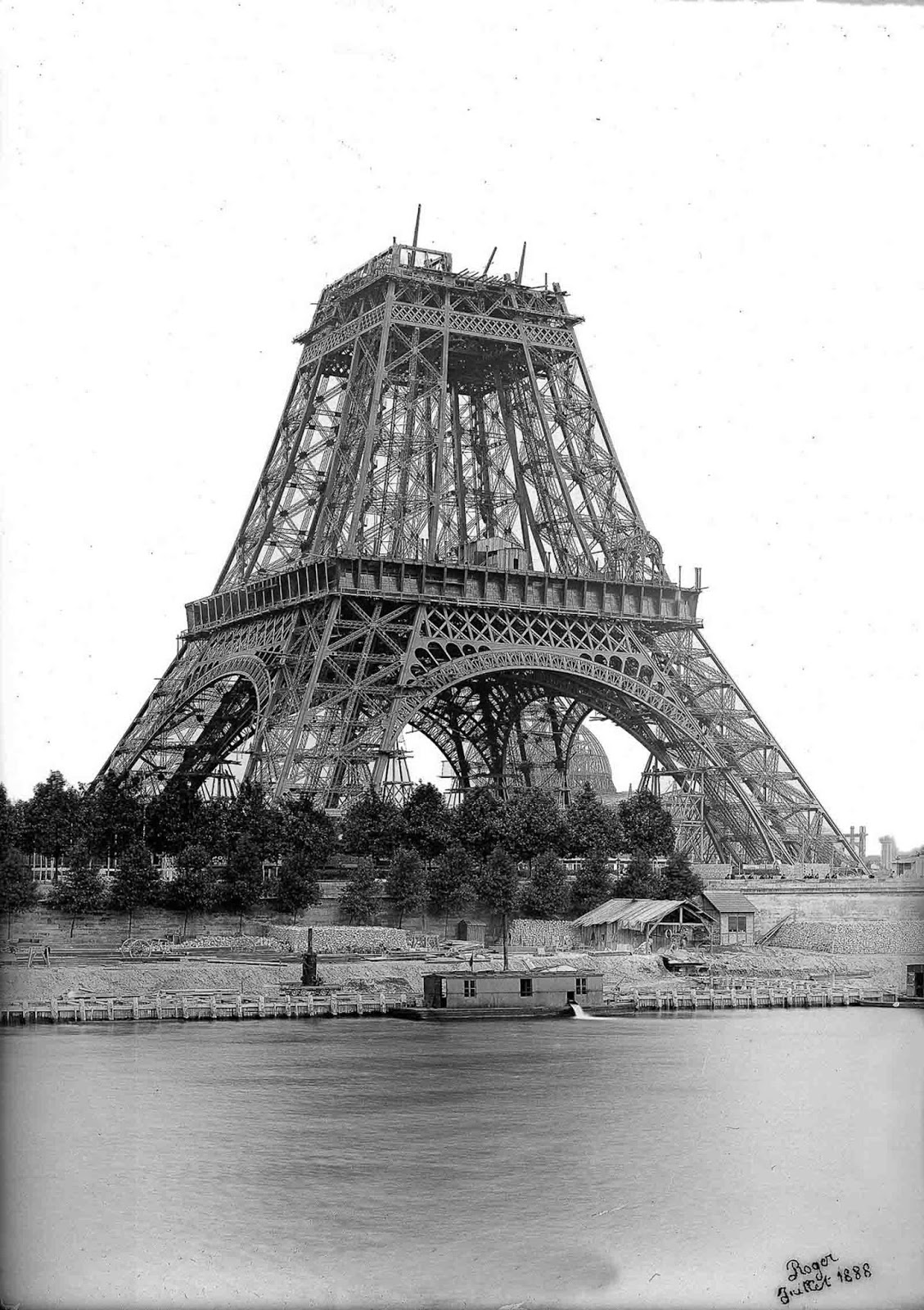

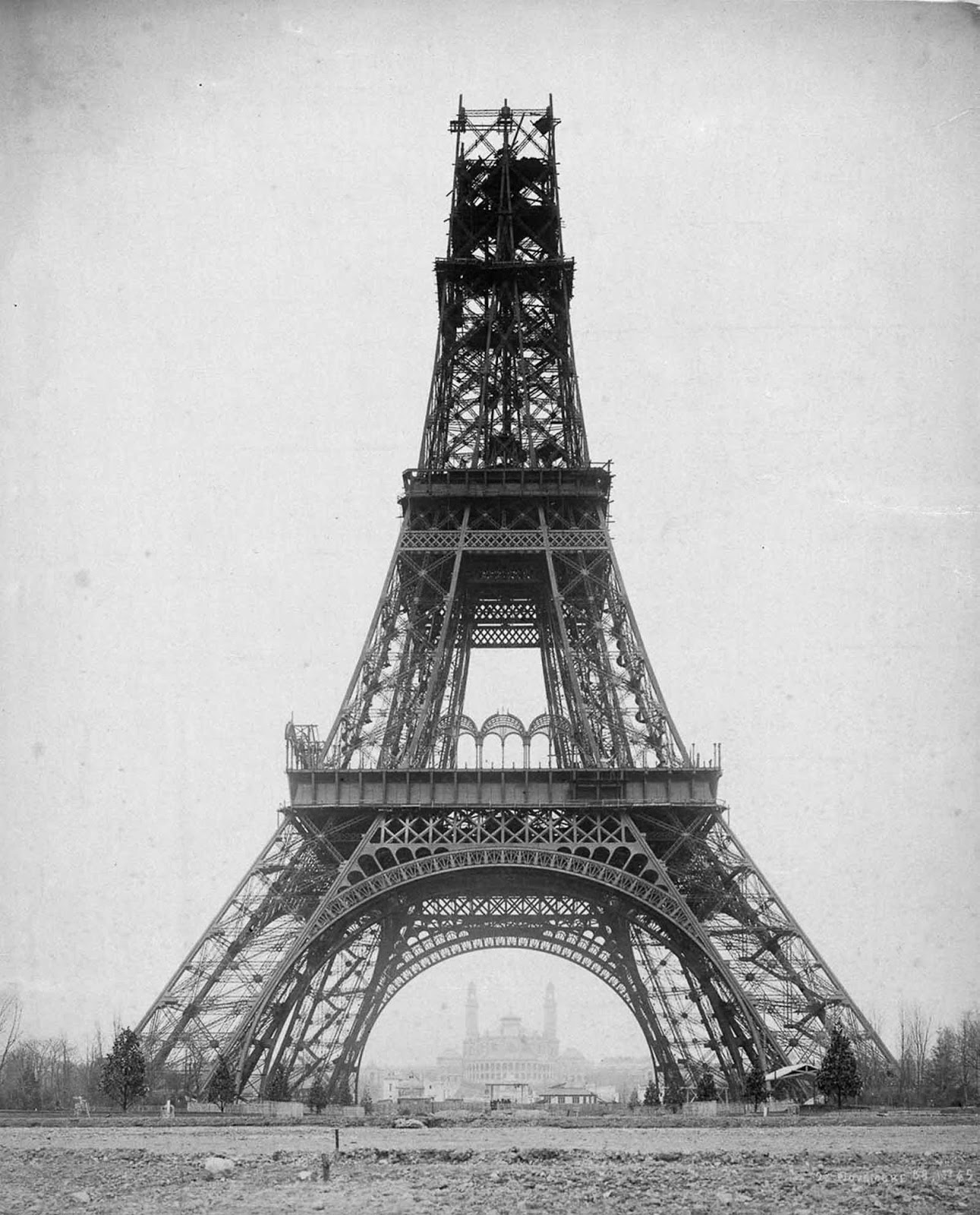

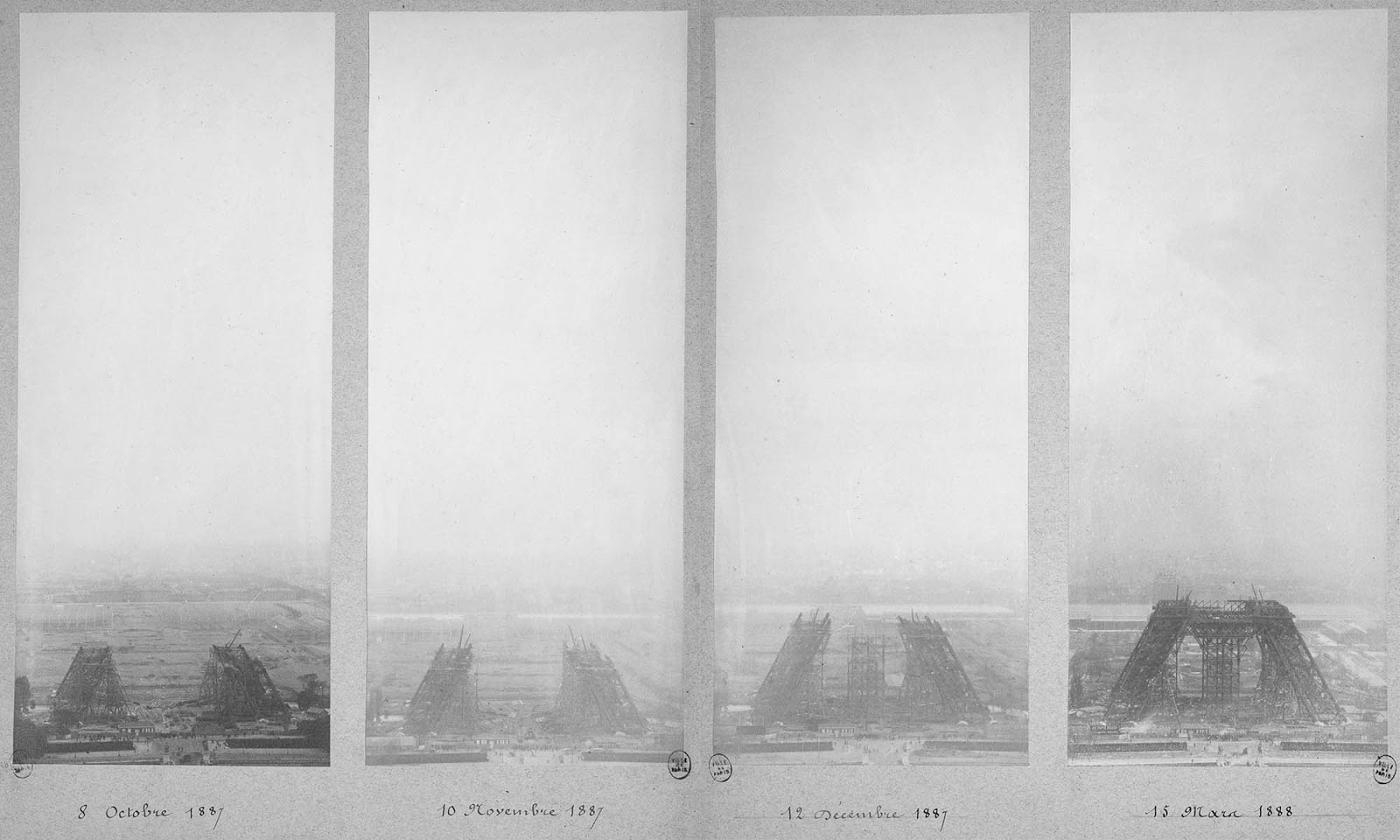

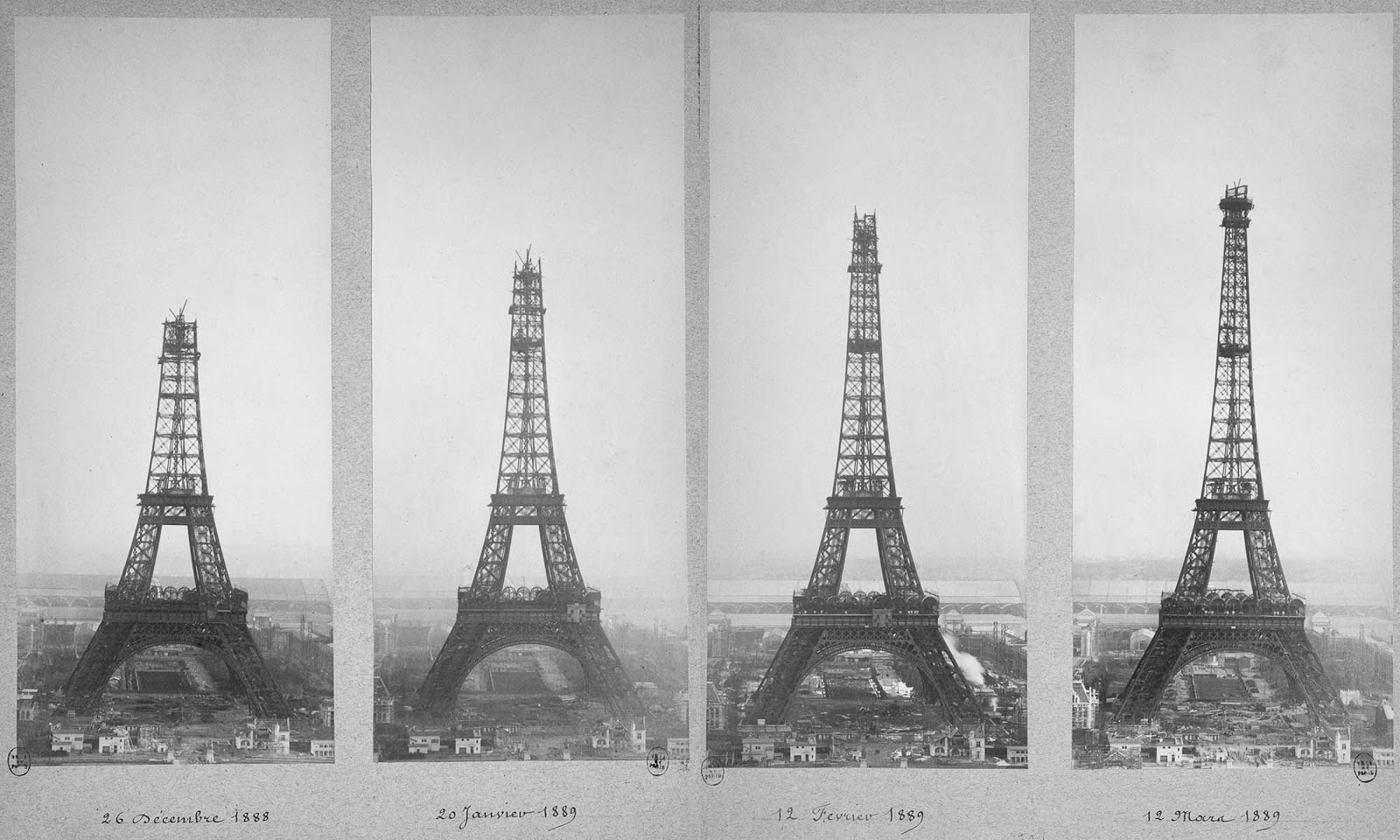

The commission was granted to Eiffel et Compagnie, a consulting and construction firm owned by the acclaimed bridge builder, architect, and metals expert Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel. While Eiffel himself often receives full credit for the monument that bears his name, it was one of his employees—a structural engineer named Maurice Koechlin—who came up with and fine-tuned the concept. The assembly of the supports began on July 1, 1887, and was completed twenty-two months later. All the elements were prepared in Eiffel’s factory located at Levallois-Perret on the outskirts of Paris. Each of the 18,000 pieces used to construct the Tower were specifically designed and calculated, traced out to an accuracy of a tenth of a millimeter, and then put together forming new pieces around five meters each. A team of constructors, who had worked on the great metal viaduct projects, were responsible for the 150 to 300 workers on-site assembling this gigantic erector set. All the metal pieces of the tower are held together by rivets, a well-refined method of construction at the time the Tower was constructed. First, the pieces were assembled in the factory using bolts, later to be replaced one by one with thermally assembled rivets, which contracted during cooling thus ensuring a very tight fit. A team of four men was needed for each rivet assembled: one to heat it up, another to hold it in place, a third to shape the head and a fourth to beat it with a sledgehammer. Only a third of the 2,500,000 rivets used in the construction of the Tower were inserted directly on site. The uprights rest on concrete foundations installed a few meters below ground-level on top of a layer of compacted gravel. Each corner edge rests on its own supporting block, applying to it a pressure of 3 to 4 kilograms per square centimeter, and each block is joined to the others by walls. On the Seine side of the construction, the builders used watertight metal caissons and injected compressed air, so that they were able to work below the level of the water. The tower was assembled using wooden scaffolding and small steam cranes mounted onto the tower itself. The assembly of the first level was achieved by the use of twelve temporary wooden scaffolds, 30 meters high, and four larger scaffolds of 40 meters each. “Sandboxes” and hydraulic jacks – replaced after use by permanent wedges – allowed the metal girders to be positioned to an accuracy of one millimeter. It only took five months to build the foundations and twenty-one to finish assembling the metal pieces of the Tower. On March 31, 1889, Eiffel celebrated the completion of principal structural work by leading a group of press and officials on a tour of the tower — via the stairs. Upon reaching the top with the hardiest of the party, Eiffel raised a French flag to the booms of a 25-gun salute. There was still work to be done, particularly on the lifts (elevators) and facilities, and the tower was not opened to the public until nine days after the opening of the exposition on 6 May; even then, the lifts had not been completed. The tower was an instant success with the public, and nearly 30,000 visitors made the 1,710-step climb to the top before the lifts entered service on 26 May. Millions of visitors during and after the World’s Fair marveled at Paris’ newly erected architectural wonder. Not all of the city’s inhabitants were as enthusiastic, however: Many Parisians either feared it was structurally unsound or considered it an eyesore. The novelist Guy de Maupassant, for example, allegedly hated the tower so much that he often ate lunch in the restaurant at its base, the only vantage point from which he could completely avoid glimpsing its looming silhouette. Eiffel had a permit for the tower to stand for 20 years. It was to be dismantled in 1909 when its ownership would revert to the City of Paris. The City had planned to tear it down (part of the original contest rules for designing a tower was that it should be easy to dismantle) but as the tower proved to be valuable for communication purposes, it was allowed to remain after the expiry of the permit. (Photo credit: National Archives of France / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe