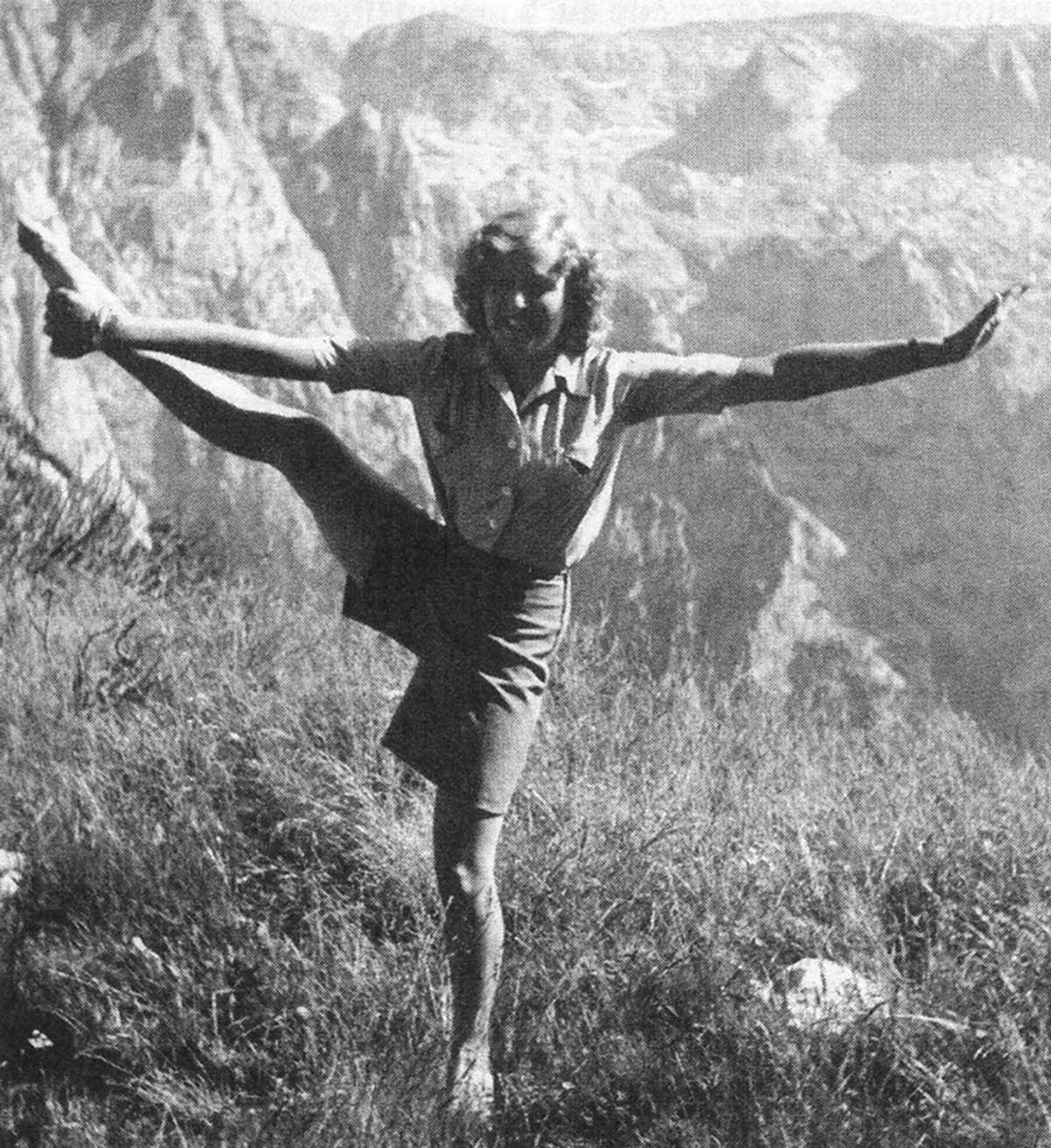

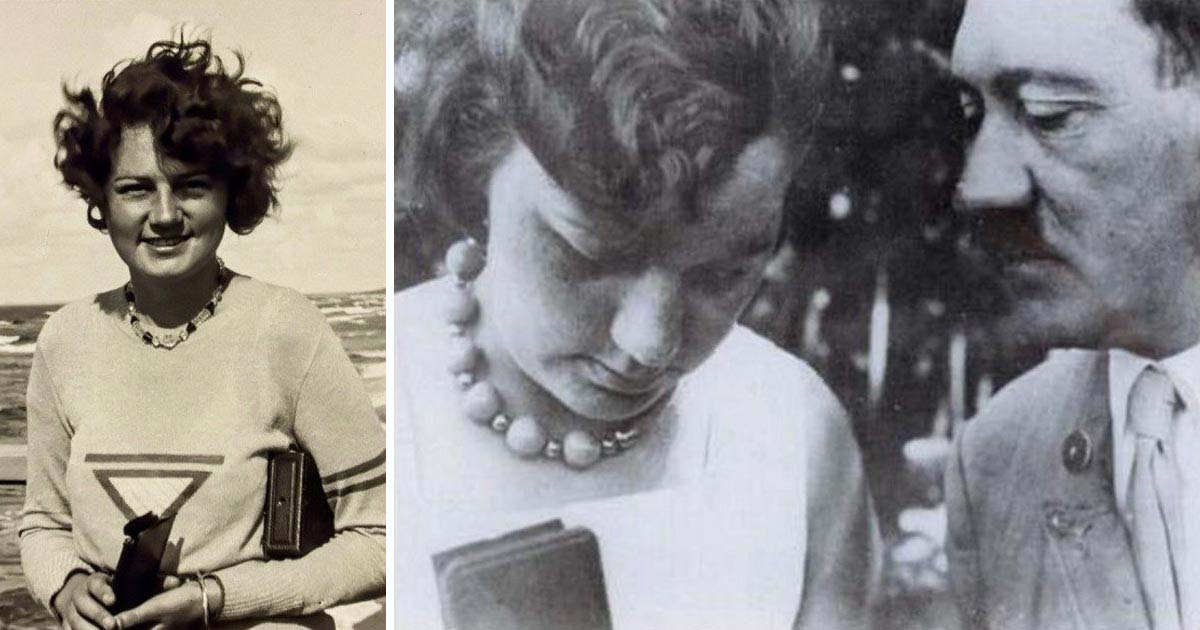

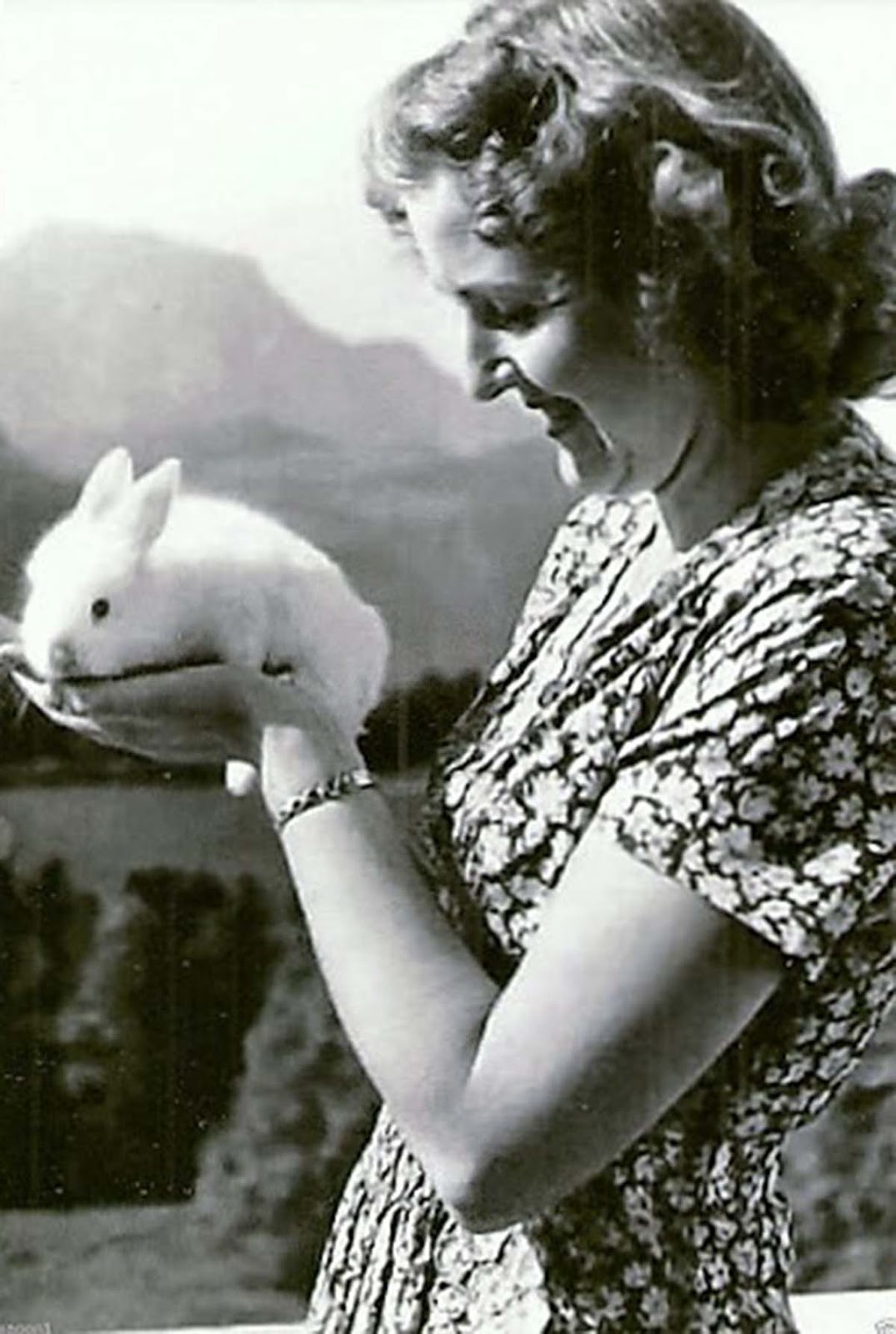

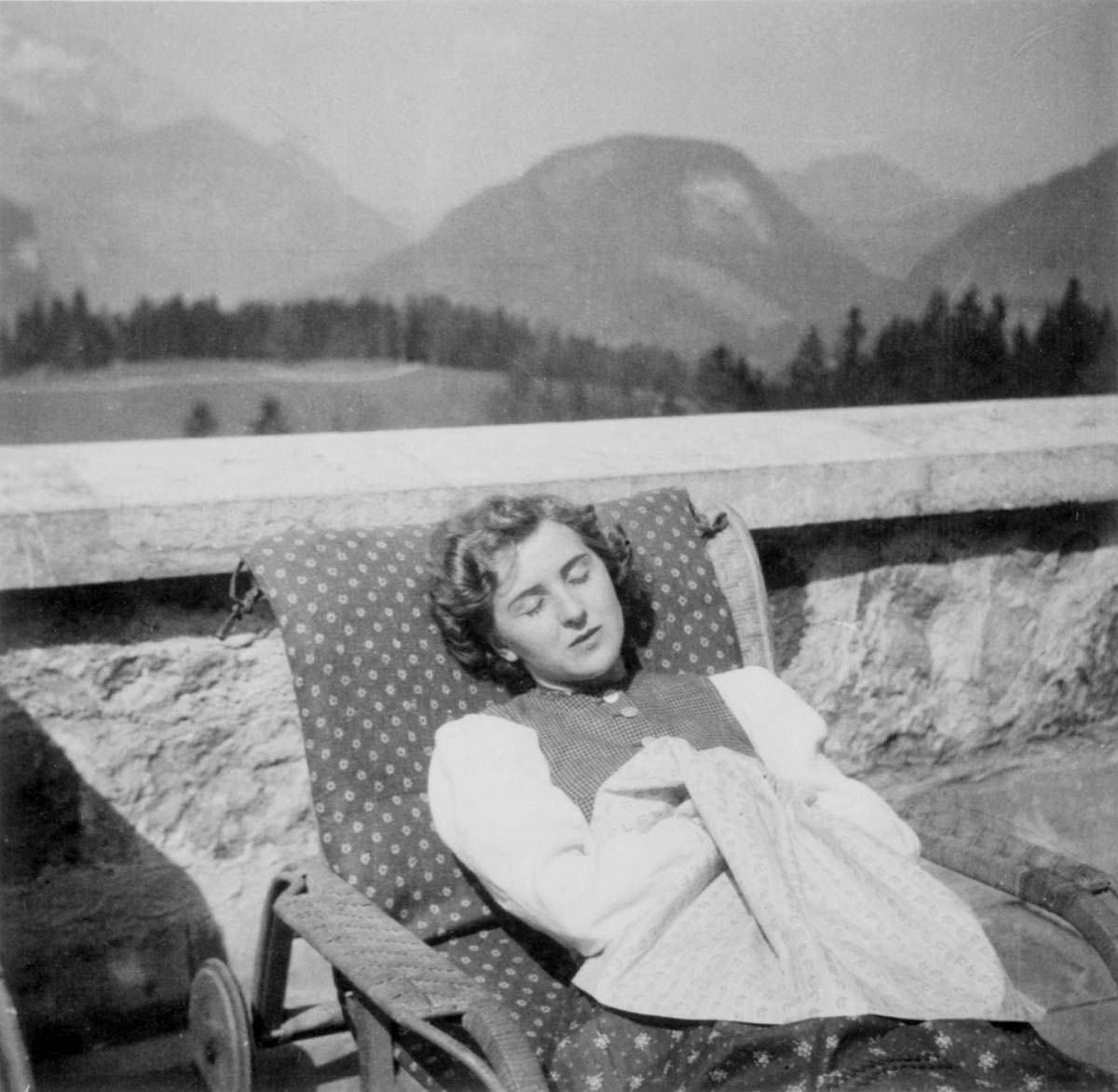

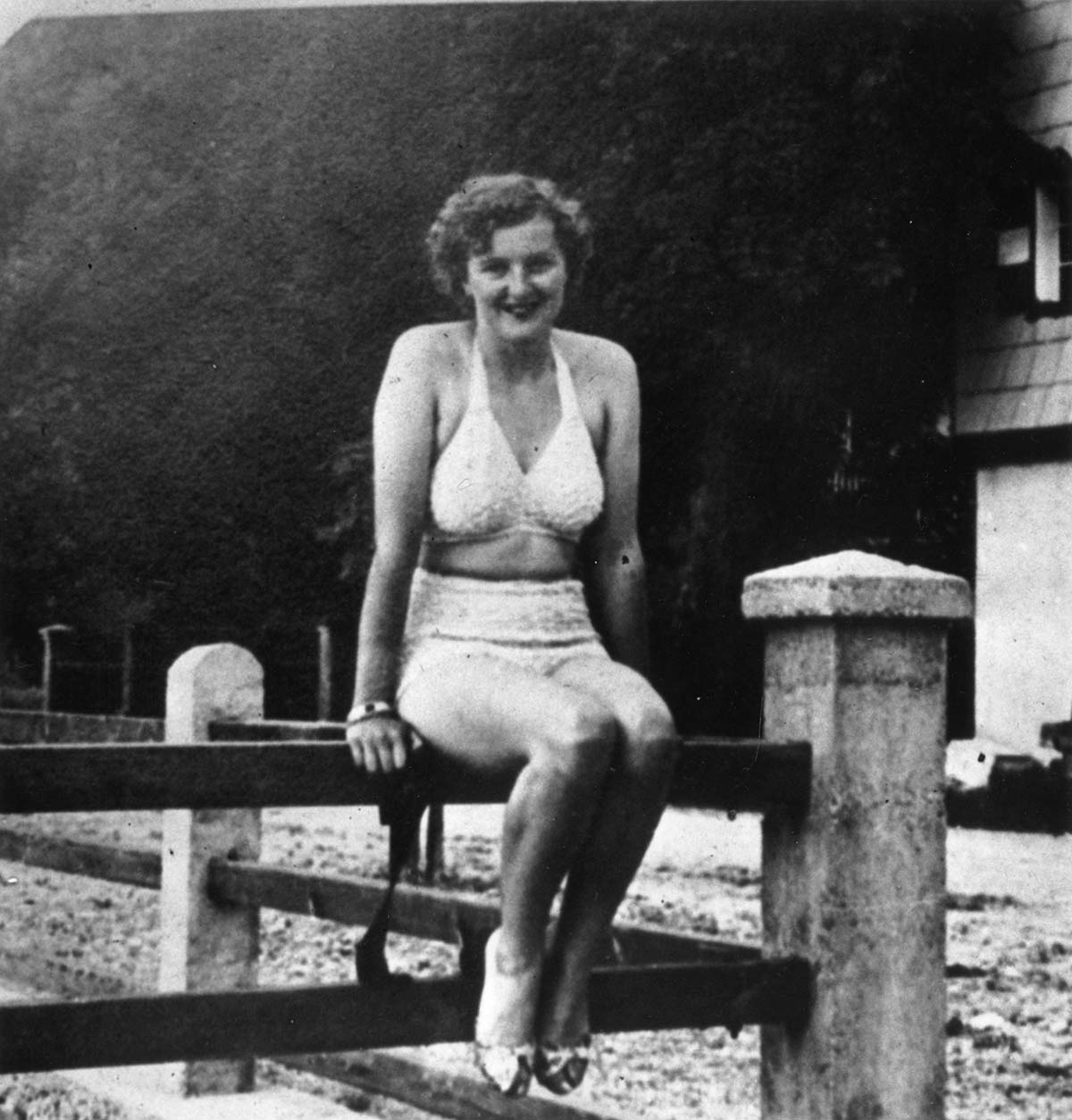

Eva Brain was born into a lower middle-class Bavarian family and was educated at the Catholic Young Women’s Institute in Simbach-am-Inn. In 1929 she was employed as a saleswoman and model in the shop of Heinrich Hoffman, Hitler’s photographer, and in this way met Hitler. Braun was a photographer, and she took many of the surviving color photographs and films of Hitler. Many of the pictures shown in this article were taken by Eva or at least requested and arranged by her. In 1929, at 17 years old, Eva was working at the studio as usual when she met a customer who introduced himself as ‘Herr Wolff.’ It was Adolf Hitler. Eva later told her sister Ilse: “I’d stayed on after closing time to file some papers and I’d climbed up a ladder to fetch the files kept on the top shelves of the cupboard. At that moment the boss came in accompanied by a man of uncertain age with a funny mustache, a light-colored, English-style overcoat, and a big felt hat in his hand.” Hoffmann sent her out to buy beer and sausages and then invited Eva to join them. She recalled in her diary: “The elderly gentleman (Hitler) was paying me compliments. We talked about music and a play at the Staatstheater, as I remember, with him devouring me with his eyes all the time.” Adolf Hitler was 23 years older than Eva. Apparently, Eva wrote Hitler a note at this first meeting. She stuffed it in his pocket. Whatever it said, it was something fresh. After looking at it, Hitler asked if she was joking. She said no, she really liked him. This was the start of their relationship. Eva later recalled in a letter to Adolf Hitler: “From our first meeting on, I have promised myself to follow you wherever you go, even to death. You know that I live only for your love.” Hitler liked Eva from the start. It probably did not hurt that Eva was in the photography business, and he was one of the most photographed men of his time who used pictures to create mass appeal. During this time, Hitler lived with his half-niece, Geli Raubal, in an apartment at Prinzregentenplatz 16 in Munich. On 18 September 1931, Raubal was found dead in the apartment with a gunshot wound, an apparent suicide with Hitler’s pistol. Hitler was in Nuremberg at the time. Rumors immediately began in the media about physical abuse, a possible sexual relationship, an infatuation by Raubal for her uncle, and even murder. The historian Ian Kershaw maintains that “whether actively sexual or not, Hitler’s behavior towards Geli has all the traits of a strong, latent at least, sexual dependence.” The police ruled out foul play; the death was ruled a suicide. Hitler was devastated and went into an intense depression. Hitler began seeing more of Braun after Raubal’s suicide. Braun herself attempted suicide on 10 or 11 August 1932 by shooting herself in the chest with her father’s pistol. Historians feel the attempt was not serious but was a bid for Hitler’s attention. After Braun’s recovery, Hitler became more committed to her and by the end of 1932, they had become lovers. She often stayed overnight at his Munich apartment when he was in town. Beginning in 1933, Braun worked as a photographer for Hoffmann. This position enabled her to travel—accompanied by Hoffmann—with Hitler’s entourage as a photographer for the Nazi Party. Later in her career, she worked for Hoffman’s art press. According to a fragment of her diary and the account of biographer Nerin Gun, Braun’s second suicide attempt occurred in May 1935. She took an overdose of sleeping pills when Hitler failed to make time for her in his life. Apparently, she thought Hitler was seeing other women – which he apparently was. Hitler provided Eva and her sister with a three-bedroom apartment in Munich that August, and the next year the sisters were provided with a villa in Bogenhausen at Wasserburgerstr. He also made her his ‘private secretary’ so she could come and go without too much fuss. She would travel with him at times, too, at least to nearby events, and stay hidden away in nearby rooms. Braun was a member of Hoffman’s staff when she attended the Nuremberg Rally for the first time in 1935. Hitler’s half-sister, Angela Raubal (the dead Geli’s mother), took exception to her presence there and was later dismissed from her position as housekeeper at his house in Berchtesgaden. Researchers are unable to ascertain if her dislike for Braun was the only reason for her departure, but other members of Hitler’s entourage saw Braun as untouchable from then on. Hitler and Eva also corresponded regularly. In “The Psychopathic God,” Robert Waite renders a letter Adolf Hitler wrote to Eva Braun shortly after the attempt on his life in July 1944: “Mein Liebes Tschapperl (“My sweet little girl”), Don’t worry about me. I’m fine though perhaps a little tired. I hope to come home soon and then I can rest in your arms. I have a great longing for rest, but my duty to the German people comes before everything else. Don’t forget that the dangers I encounter don’t compare with those of our soldiers at the Front. I thank you for the proof of your affection and ask you also to thank your esteemed father and your most gracious mother for their greetings and good wishes. I am very proud of the honor – please tell them that – to possess the love of a girl who comes from such a distinguished family. I have sent to you the uniform I was wearing during the unfortunate day. It is proof that Providence has protected me and that we have nothing more to fear from our enemies. From my whole heart, your A.H.” “Tschapperl” is a word in an Austrian dialect that doesn’t have a good translation. It is something along the lines of “My sweet little cupcake” or “Honeybunny.” No matter how you translate it, someone will disagree and have a “better” translation. Let’s just say that Hitler would not have used it with any of his generals. Eva retained her interest in film and photography throughout her days at Berchtesgaden. Many of the behind-the-scenes photographs at the Berghof and elsewhere were taken by Eva, including extensive and sometimes elaborate movies (with title cards, fancy editing, and the works). Altogether, the Library of Congress has four and a half hours of Eva’s home movies, many in color. Hitler wished to present himself in the image of a chaste hero; in the Nazi ideology, men were the political leaders and warriors, and women were homemakers. He believed that he was sexually attractive to women and wished to exploit this for political gain by remaining single, as he felt marriage would decrease his appeal. He and Braun never appeared as a couple in public; the only time they appeared together in a published news photo was when she sat near him at the 1936 Winter Olympics. The German people were unaware of Braun’s relationship with Hitler until after the war.

Eva Braun and Albert Speer

Albert Speer had a lot to say about Eva Braun and is one of our few primary sources. Speer is a special case, because he was one of the very few from the inner circle who survived the war, was interrogated immediately after it, and then spent decades reminiscing about it and elaborating on his earlier characterizations. The public image of Speer is of someone who to one extent or another rehabilitated himself by being properly repentant, making various noises about rejecting Hitler during the last days of the Third Reich and uttering socially conscious statements after entering the book-peddling circuit of the 1960s and 1970s. It is important for historians to remember that the picture painted by our sources reflects not just on the people being talked about, but the speaker himself, and Speer did not have a consistent view of Eva Braun over time. That said, Speer’s recollections remain of value even if they are, shall we say, nuanced because Speer at least knew both Hitler and Eva Braun and lived to tell about it. Albert Speer gave a fairly generous portrayal of Braun (who already was assumed to be dead at this point). He called her a “modest woman” who did not “exploit” her position nor try to influence Hitler. The quote everyone uses is this: “For all writers of history she is going to be a disappointment”. He goes on to say that she was very athletic (as can be seen in her self-made films). He does shade her slightly: “Outwardly she often appeared conceited and haughty. That, however, was due to her inferiority complex; for her social position at OBERSALZBERG was not clearly defined [emphasis in original]”. Then he quickly cleans that up with another quote that is widely bandied about: “Of all those who during the last weeks lived together in the BERLIN shelter, she was one of the bravest, and probably also the most intelligent. She wanted to stay in BERLIN and die with HITLER [emphasis in original].” He emphasized that there were genuine feelings of love between the two. After noting that Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels had acted as a procurer of women for him during the 1930s, Speer notes: He [Hitler] appears, however, to have always remained true to the woman he loved, Fraulein EVA BRAUN. Her love was very significant for him; he spoke of her with great respect and deep reverence. He knew that he could have had any number of women; this he rejected, for, as he jokingly said, he did not know whether they would prefer him as “Reich Chancellor” or as ADOLF HITLER [emphasis in original]. However, after spending 20 years in Spandau Prison, Albert Speers’ thoughts about Eva Braun changed from his statements in 1945. His books written during that stay and afterward such as “Inside the Third Reich” and “Spandau: The Secret Diaries” tell a much different tale. Here is a quote from a 1976 interview with Speer published in People Magazine, when his latest book was riding high on the sales charts. The question posed was, “Was Hitler’s marriage to Eva Braun just before his suicide merely for the record, related to his concern with his place in posterity?”: “It could have been. On the other hand, it could also have been because he was really touched that she, against his wishes, came to join him in Berlin at the end. It would be wrong to assume that Hitler was a man without the ability to show and experience sentimental feelings. Nevertheless, his relationship to Eva Braun was abominable. He always treated her like a fifth-rate person. I pitied her.” Such talk about treating Eva like a “fifth-rate person” and pitying her is a much different picture than Speer gave in his 1945 interrogation, where, without prodding, he mentions Hitler’s “great respect and deep reverence” for Eva Braun. By 1976, Speer basically makes it sound as if Eva was one step from being sent to a concentration camp. Of course, this latter characterization perfectly matched the stereotypes of the time of Hitler as a pure monster with no capacity for love or any real emotions or affection. The quote also hints at Eva as a victim – a quality that would help redeem virtually anyone in the 1970s, when victimhood was next to saintliness. In effect, with Germany marching Leftward, Speer has drawn the measure of his audience and tailored his message to it. Speer’s 1945 portrayal, however, more closely matches other sources. Draw your own conclusions, however, we should trust statements made closer in time to events being described as opposed to those made 30 years later when the world has changed, and attributing any positive qualities whatsoever to Hitler might impact book sales and invitations to fancy soirées.

Eva Braun’s Final Days

In early April 1945, Braun traveled from Munich to Berlin to be with Hitler at the Führerbunker. She refused to leave as the Red Army closed in on the capital. After arriving in the bunker, Eva at first was hopeful. This actually was in line with the prevailing sentiment in the bunker, because the final Soviet assault on Berlin which began on 16 April appeared to be stalling out. In fact, the Wehrmacht defenses on the Oder were engaged in a death struggle which gave the German high command hope for several days. General Keitel, for instance, claimed that if an attack could be contained for three days, it had failed, and the 19th was the fourth day of the Soviet offensive. Anna Maria Sigmund in “The Women of the Nazis,” claims to have seen letters typed by Eva (or perhaps by Hitler’s secretaries for Eva) to friend Herta Schneider. The Schneider estate kept the letters before auctioning them off to a private collector sometime around the turn of the 21st century. How Schneider got the letters in the Reich’s final days is a bit of a mystery, but Hitler still held complete control over everything still under German control and could get things such as mail delivery done. In a letter dated April 19th, 1945, Eva writes to Schneider in an optimistic vein: We already hear the artillery fire from the eastern front and bombs fall from attack planes every day… I’m very happy right now to be close to [Hitler]… I am convinced that everything will turn out alright at the end and [Hitler] is hopeful as he seldom is. The optimism did not last. It is generally accepted that the German front around Berlin finally caved in the very next day, Hitler’s birthday (April 20th, 1945). A couple of days later, Hitler had his famous breakdown in which he finally accepted that the war was lost. That day, 22 April 1945, Eva wrote another letter to Schneider (apparently her last): “We are fighting here until the last but I’m afraid the end is threatening closer and closer… I cannot tell friends what I personally suffer from the Fuhrer… I cannot understand how everything could be so, but one cannot believe in a God!… Greetings to my friends, I’m dying how I’ve lived. It’s not difficult for me. You know that.” It’s interesting that Eva refers to her man in this final letter as “the Fuhrer,” not by his name. Formalities were retained up to the last. The situation in the bunker deteriorated further after Albert Speer left on the 24th, with no military or diplomatic relief possible. Everyone understood the situation, apparently, Hitler most of all, which no doubt accounts for his sour mood to which Eva obliquely refers in her letters to Schneider. Speer noted that even by the 24th: “She [Eva Braun] had detached herself from life. She was calm and determined and, at this time, one of the few who were faithful to Adolf Hitler – perhaps the only one. Earlier, Hitler had already asserted with resignation that he had only one friend who would remain loyal to the end in his decisive hour, and that was EVA BRAUN [emphasis in original].” As the days went by, Hitler had Eva’s brother-in-law Hermann Fegelein shot for being a nuisance (“desertion,” supposedly). It was the last gasp of tyranny. Test pilot Hanna Reitsch made an extremely risky flight into Berlin with Luftwaffe General Greim, but Hitler refused to leave and Reitsch flew back out again only with Greim. The end was inevitable, and Hitler better than anyone else in the world knew how little time remained. He decided on April 128th that there was no longer any need for pretense. He asked his people to find someone to marry them. Goebbels recalled that he himself had been married by one Walter Wagner, a Berlin Justice of the Peace, so someone was sent out to find him. Somewhat incredibly (during the final days in the bunker with the Soviets literally down the block!), Wagner was located in a Volkssturm detachment defending the vicinity. Wagner came in, married Hitler and Eva on the afternoon of the 29th, and then left to return to obscurity. The event was witnessed by Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann. Thereafter, Hitler hosted a modest wedding breakfast with his new wife. When Braun married Hitler, her legal name changed to Eva Hitler. When she signed her marriage certificate, she wrote the letter B for her family name, then crossed this out and replaced it with Hitler. On April 30th, 1945, Adolf Hitler held his final staff conference and was informed that the Soviets now were only a few blocks away. He had lunch as usual at 2 o’clock in the afternoon with his two secretaries and his cook. He then made systematic preparations to commit suicide. Hitler perhaps could have waited another day, but that was May Day, and he did not wish to commit suicide on a day of celebration for the Soviet Union. Hitler first supervised the poisoning of his beloved dog Blondi and her pups. Shortly after 3 p.m. on April 30th, Hitler and Eva Braun bade farewell to the staff assembled in the bunker, then retired to their private room to meet their joint fate. They bit into thin glass vials of cyanide – as he did so, Hitler also shot himself in the head with a 7.65 mm Walther pistol. After waiting a few minutes, Hitler’s valet, Heinz Linge, and Hitler’s SS adjutant, Otto Günsche, entered the small study. Heinz Linge recalled how he saw Hitler almost upright in a sitting position on a blood-soaked sofa. Eva Braun lay on the sofa beside him, but she had made no use of the revolver at her side, preferring to rely on the poison instead. A small hole showed on his right temple and a trickle of blood ran slowly down over his cheek. The pistol lay on the floor where it had dropped from his right hand. Eva Braun’s face looked perfectly normal: “It was as though she had fallen asleep…” Linge recalled. Eva was 33. The corpses were carried up the stairs and through the bunker’s emergency exit to the garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they were burned. The charred remains were found by the Soviets. By 11 May, Hitler’s dentist, Hugo Blaschke, dental assistant Käthe Heusermann, and dental technician Fritz Echtmann confirmed that the dental remains belonged to Hitler and Braun. The Soviets secretly buried the remains at the SMERSH compound in Magdeburg, East Germany, along with the bodies of Joseph and Magda Goebbels and their six children. On 4 April 1970, a Soviet KGB team with detailed burial charts secretly exhumed five wooden boxes of remains. The remains were thoroughly burned and crushed, after which the ashes were thrown into the Biederitz river, a tributary of the nearby Elbe. That is the Soviet account, and there is no hard evidence to either support it or undermine it. Not a trace remains. The rest of Braun’s family survived the war. Her mother, Franziska, died at age 96 in January 1976, having lived out her days in an old farmhouse in Ruhpolding, Bavaria. Her father, Fritz, died in 1964. Gretl gave birth to a daughter—whom she named Eva—on 5 May 1945. She later married Kurt Beringhoff, a businessman. She died in 1987. Braun’s elder sister, Ilse, was not part of Hitler’s inner circle. She married twice and died in 1979. (Photo credit: Bundesarchiv and various public libraries). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe