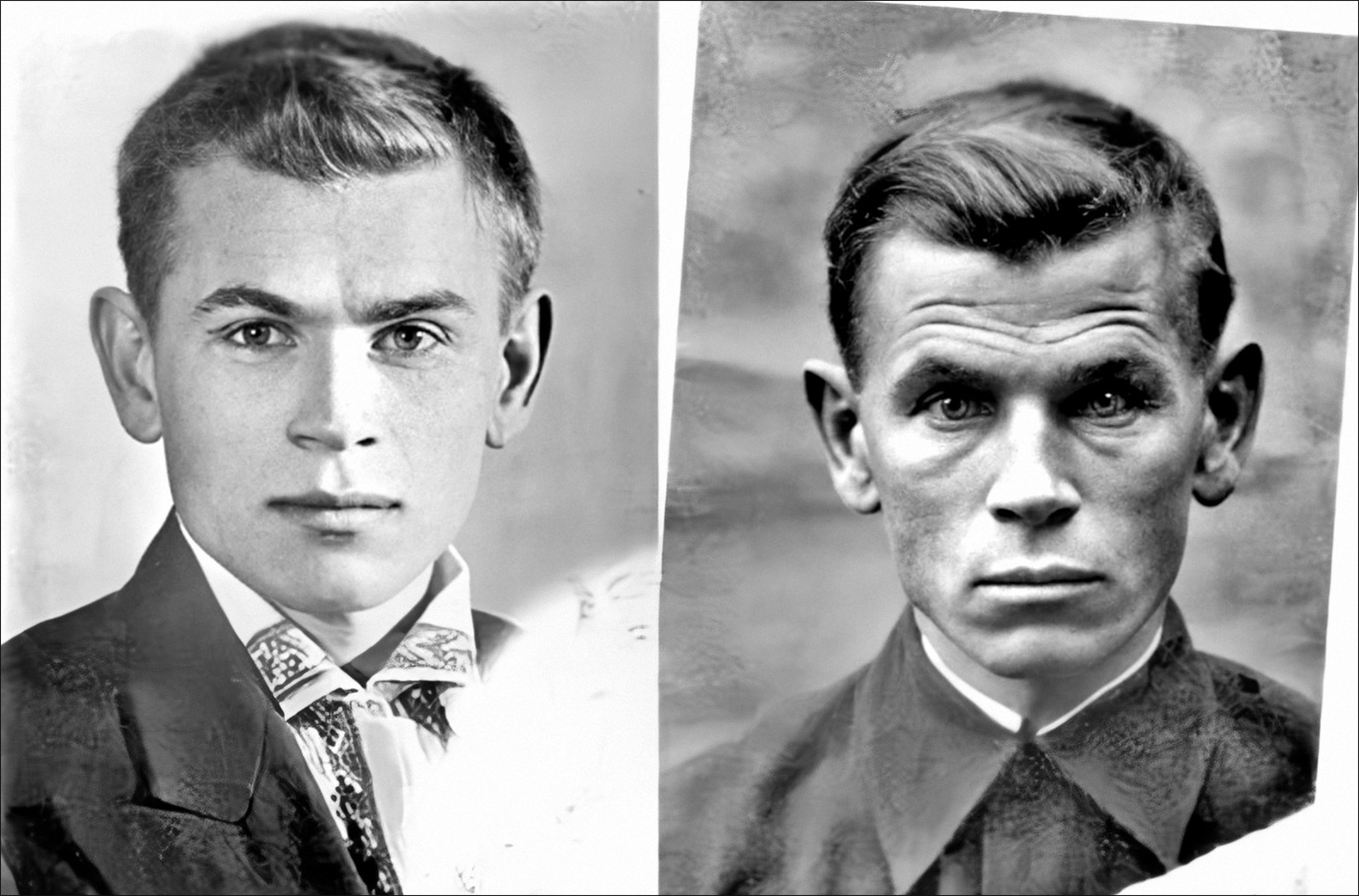

In 1941 he was a young man ready to start his creative life as an artist when Germany attacked the Soviet Union and he had to join the Army. Four years later, the difference in his face is striking. A thin and tired face, deep wrinkles, a troubled stare, this man was completely changed after witnessing 4 years of a no-rule war on the Eastern Front. Evgeny Stepanovich Kobytev was born on December 25, 1910, in the village of Altai. After graduating from pedagogical school, he worked as a teacher in the rural areas of Krasnoyarsk. His passion was painting especially portraits and panoramas from daily life. The dream of a higher artistic education came true in 1936 when he started studying at the Kyiv State Art Institute in Ukraine. In 1941 he graduated with honors from the art institute and was ready for a new artistic life. However, all his dreams were cut short on June 22, 1941, when Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The new artist voluntarily became a soldier and enlisted in one of the artillery regiments of the Red Army. The regiment was engaged in a fierce battle to protect the small town of Pripyat, which lies between Kyiv and Kharkiv. In September 1941, Kobytov was wounded in the leg and became a prisoner of war. He ended up in a notorious German concentration camp that operated out of Khorol, which was called “Khorol pit” (Dulag #160). Approximately 90 thousand prisoners of war and civilians died in this camp.

Built on the grounds of what used to be a brick factory, the Khorol camp had only one barracks; it was half-rotten and rested on posts that were leaning to one side. It was the only shelter from the autumn rains and storms. Only a few of the sixty thousand prisoners managed to cram in there. The rest had no barracks. In the barracks, people stood pressed tightly against each other. They were gasping from the stench and the vapors and were drenched with sweat. In 1943, Kobytev managed to escape from captivity and again rejoined the Red Army. He participated in various military operations throughout Ukraine, Moldova, Poland, and Germany. After the Second World War ended, he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union medal for his excellent military service during the battles for the liberation of Smila and Korsun in Ukraine. However, the High Command refused to award him the Victory over Germany medal since his military career was “spoiled” for being a prisoner of war. In post-war life, Evgeny Stepanovich Kobytev was elected as a deputy of his city council and was in charge of the cultural activities of the region. He passed away in 1973.

The Thousand Yard Stare

Chances are that, if you read about wars and the effect it has on soldiers, you may have inadvertently seen the “Thousand Yard Stare”. The first sign of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in many cases, it defined as “a vacant or unfocused gaze into the distance, seen as characteristic of a war-weary or traumatized soldier”, by Oxford dictionaries. The origin of the phrase comes from Time magazine’s publishing a painting titled “Marines Call It That 2,000 Yard Stare”, made by World War II artist and correspondent Tom Lea, although it was not explicitly called that. The painting is a 1944 portrait of a Marine at the Battle of Peleliu in Palau (Pacific theater). The most noticeable signs in a person suffering from PTSD are introversion and joylessness. This condition is characterized by frequent, undesired memories which replay the triggering event. People with this syndrome are unable to take pleasure from things they might have enjoyed in the past. They avoid the company of others and become generally more passive than before. They wish to avoid anything that will trigger memories of the traumatic event. A person with PTSD might drift out of a conversation and appear distant and withdrawn. This is known among soldiers as a “thousand-yard stare.” This is a sign that unpleasant memories have returned to haunt them.

Artwork from Evgeny Stepanovich Kobytev

After the war, Kobytev became an art teacher again. Like for most who suffered as he did, the rest of his life was impacted by the war. He had nightmares, waking up screaming in the night. But his art helped him and he eventually made a book about his experiences as a prisoner of war and soldier. “In difficult moments of life, read this book” (the inscription on the title page of the book “Khorolskaya Yama” by E.S. Kobytev, addressed to her daughter Vera Kobyteva).

(Photo credit: Russian Archives). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe