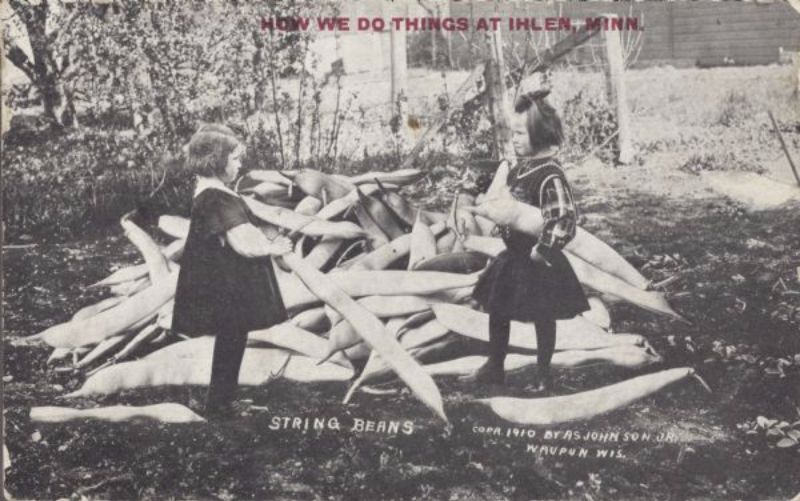

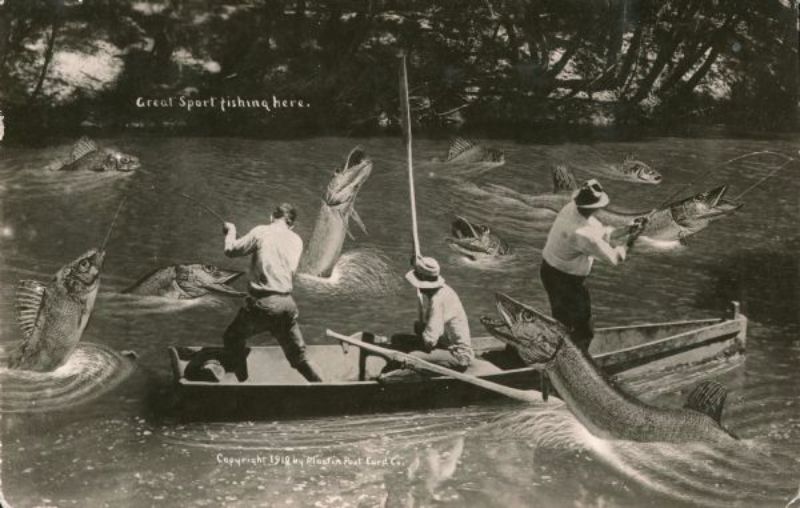

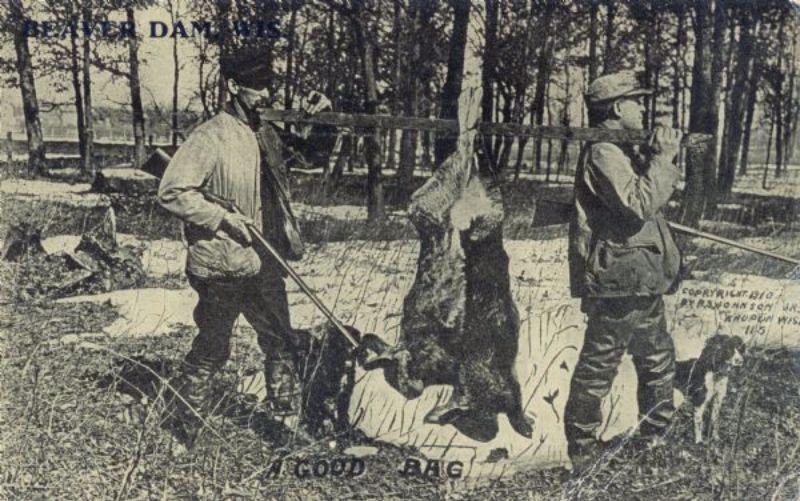

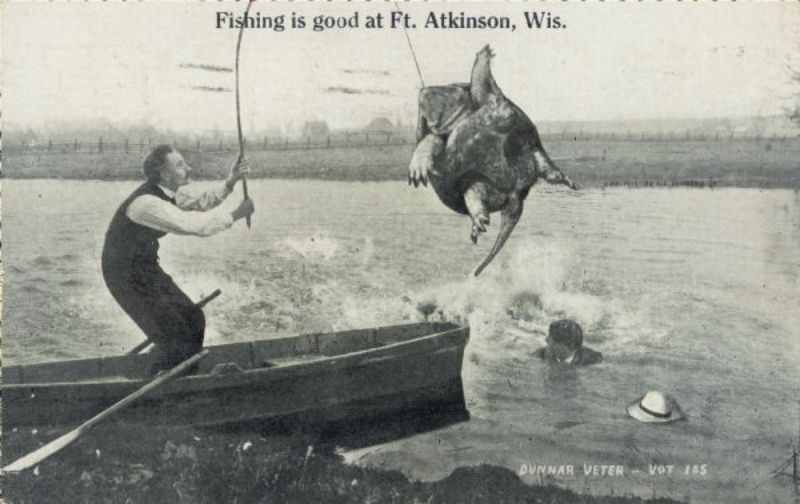

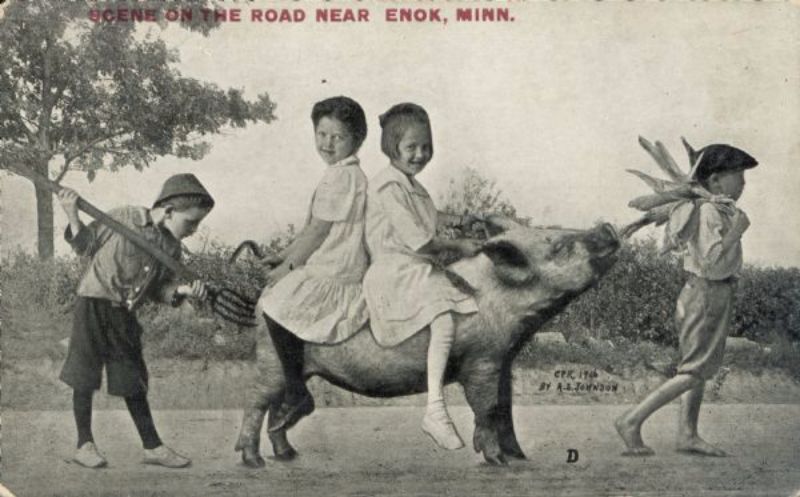

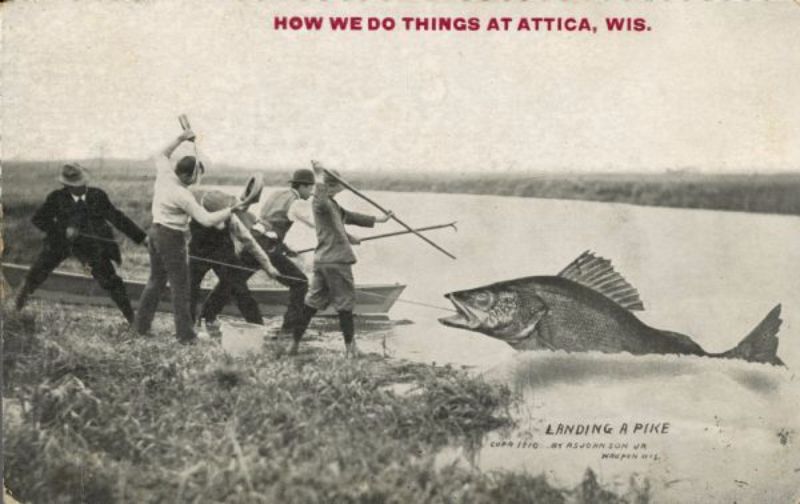

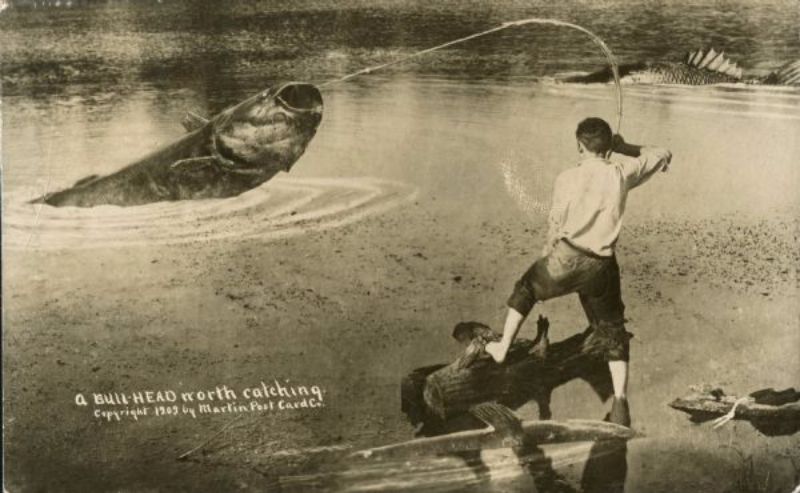

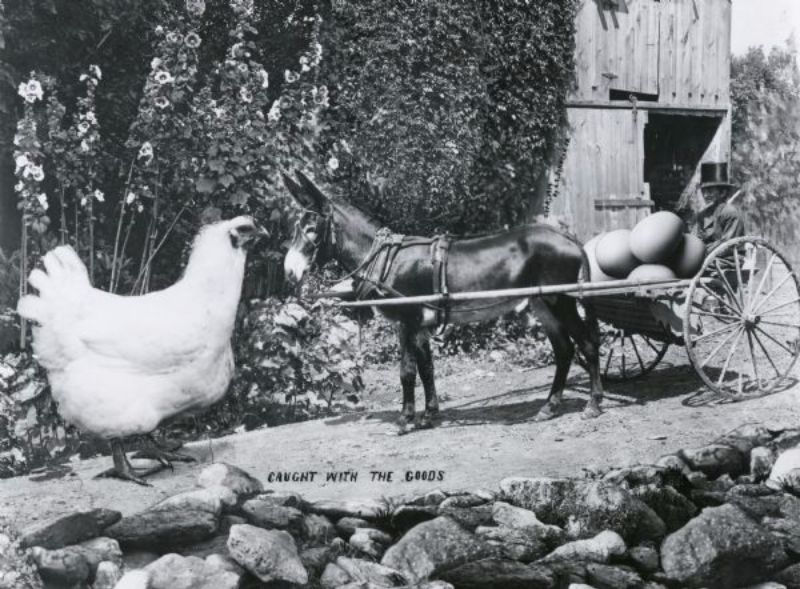

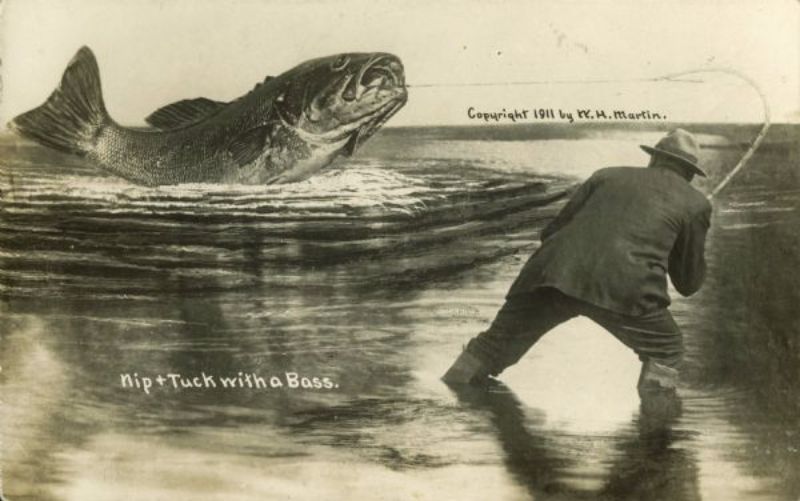

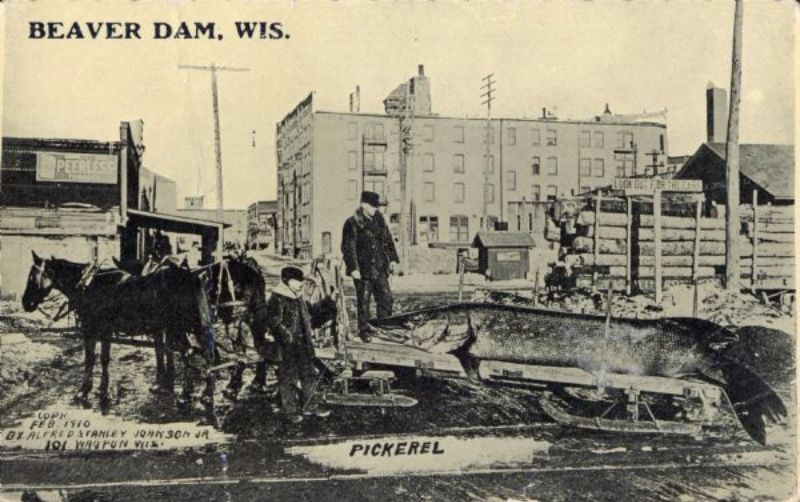

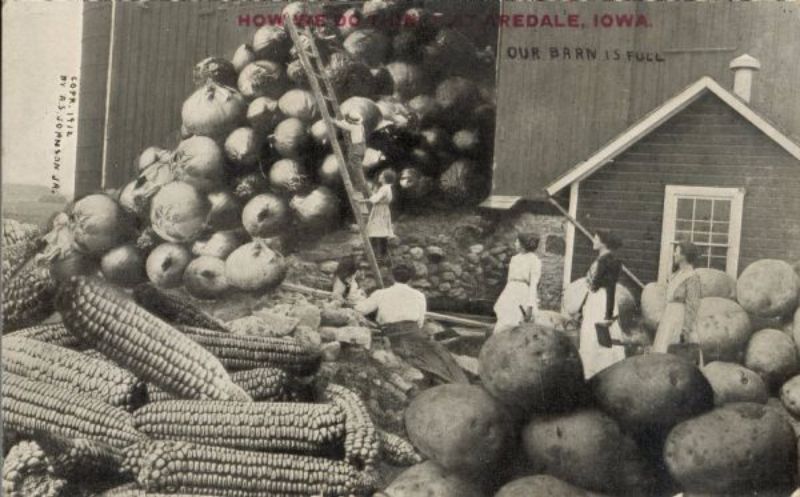

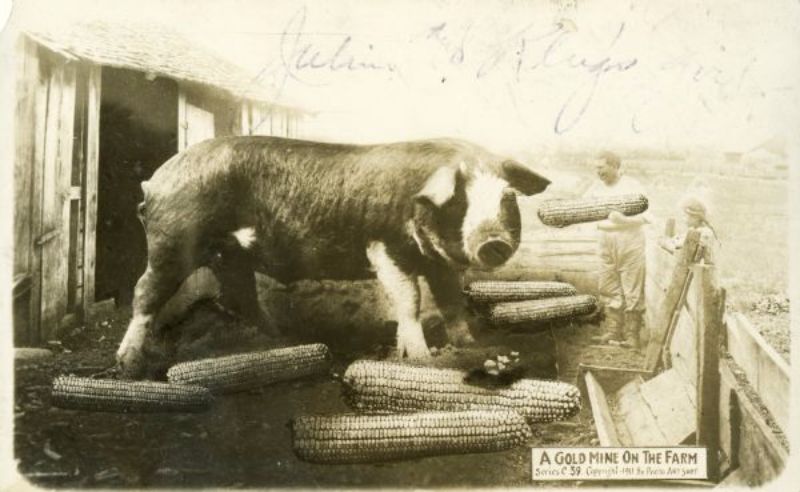

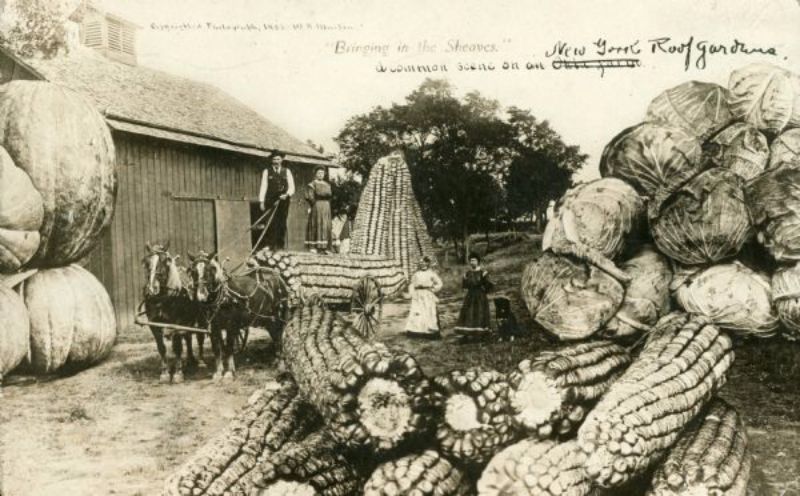

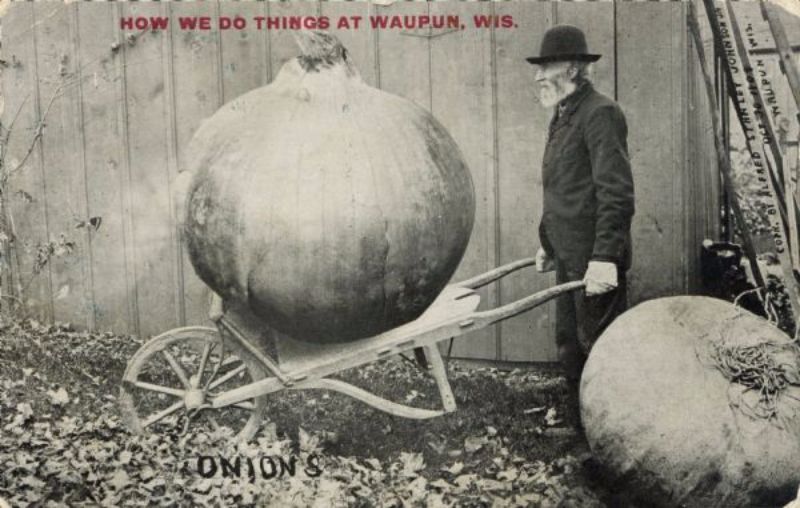

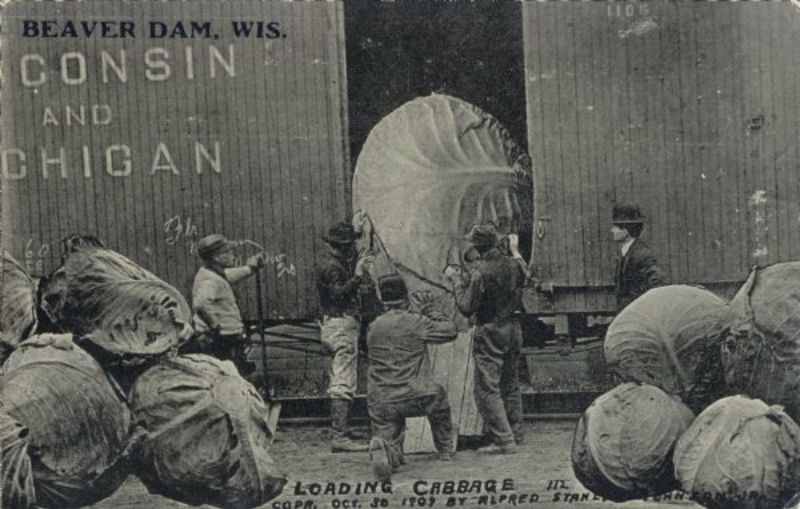

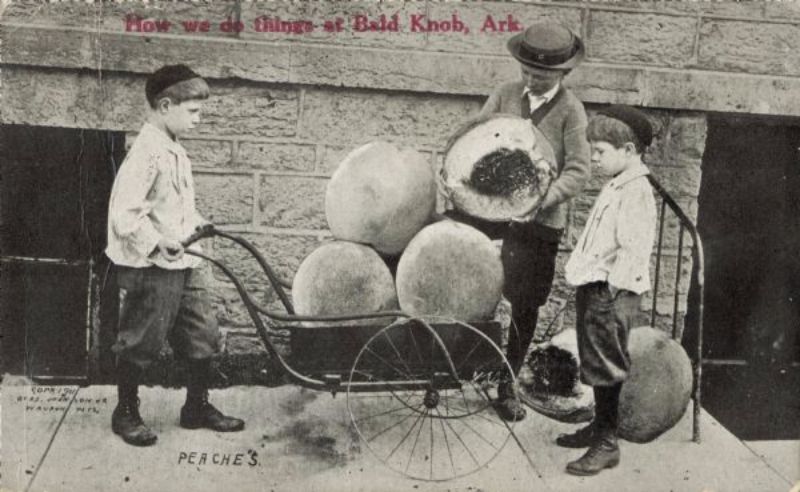

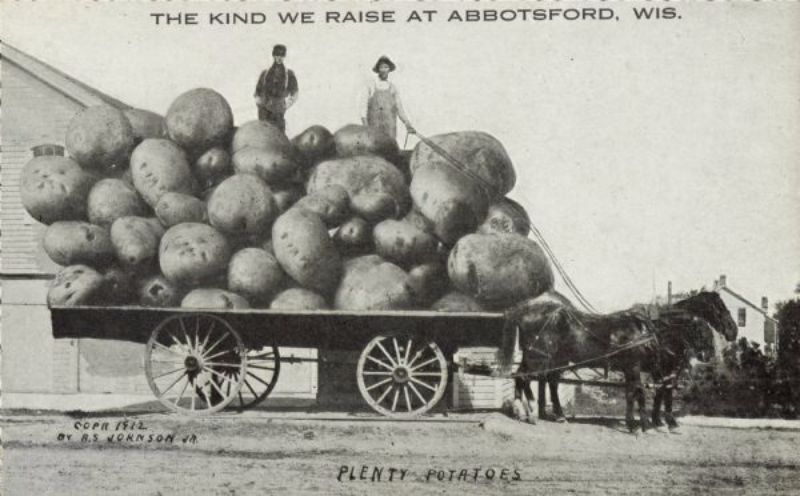

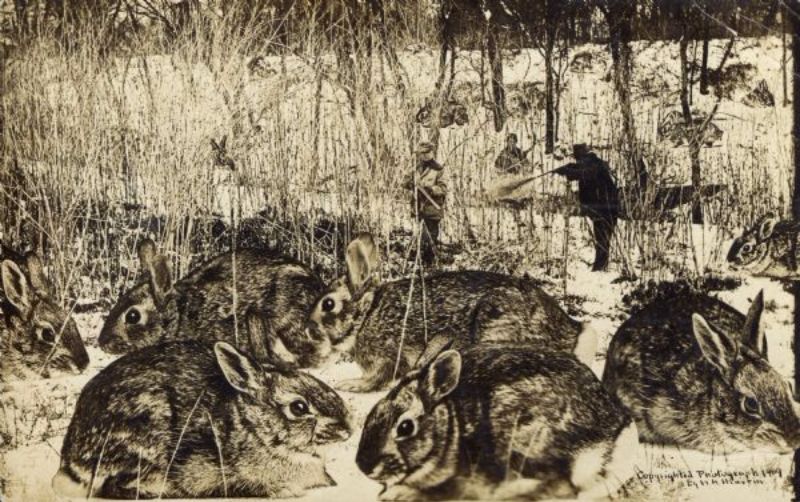

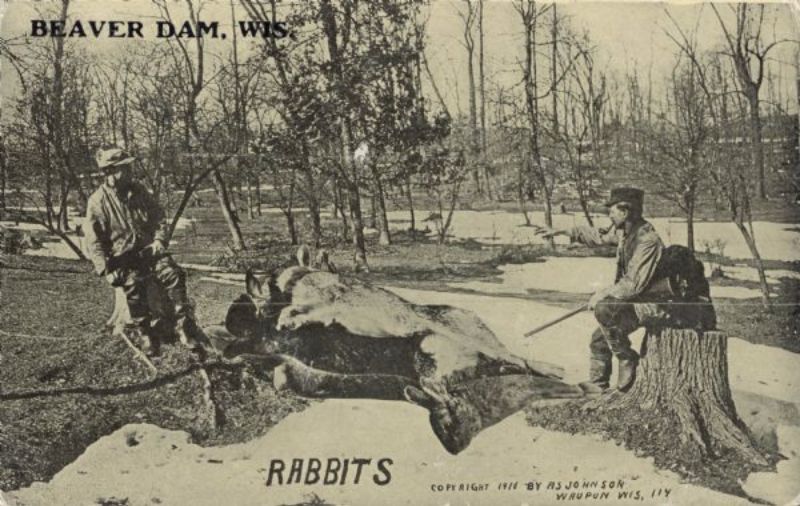

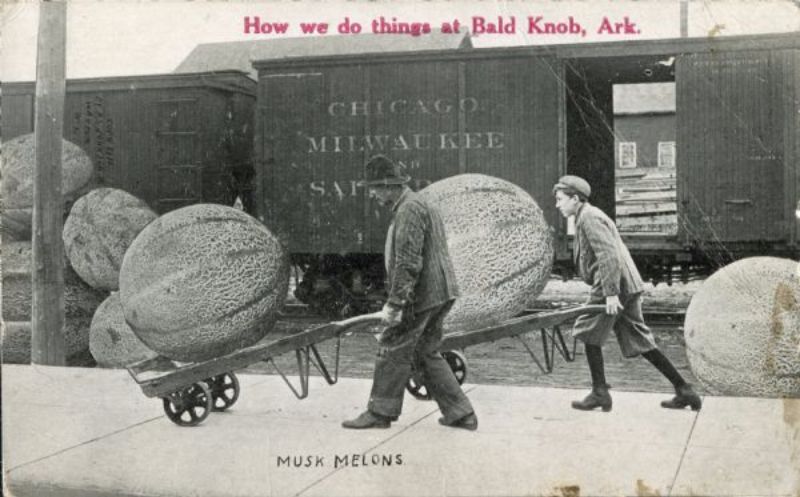

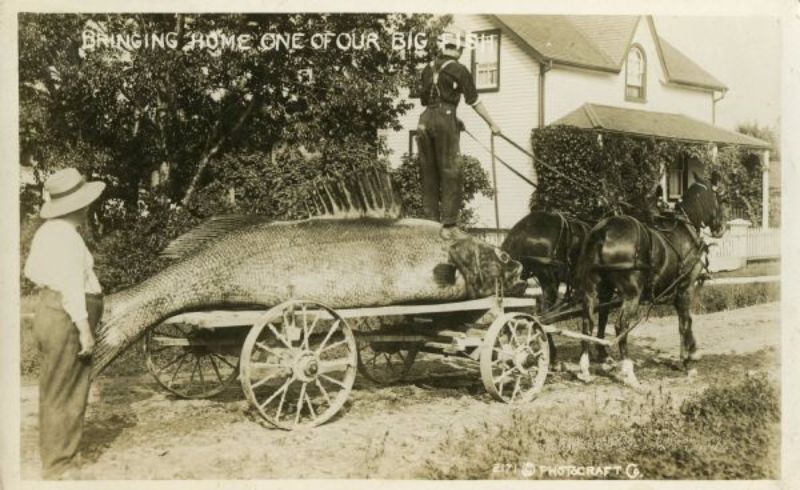

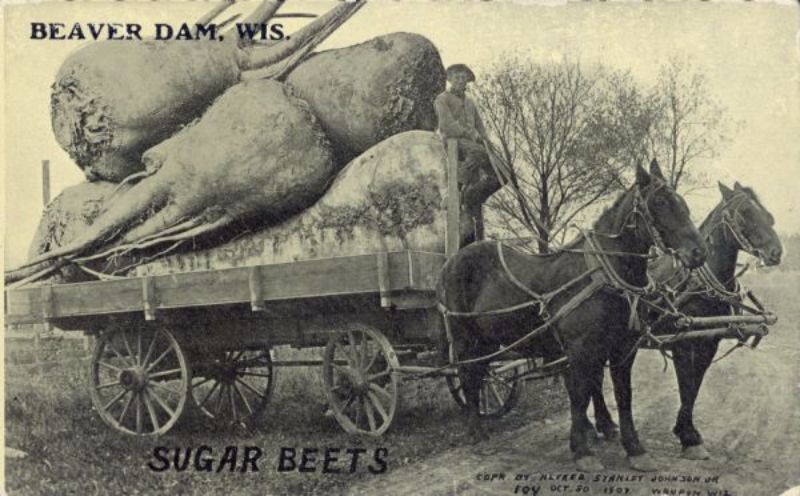

These postcards were a unique form of visual humor and satire, using manipulated photography to depict ordinary scenes or subjects in an exaggerated, comical, or absurd manner. The postcards would feature impossibly large animals and crops, often shown being carried by train or wagon, and would usually have some sort of caption to go along with them. Common themes of these postcards included giant fish being caught and massive crops being shown off, less common themes included mythical creatures such as the fur-bearing trout, and people riding oversized animals. The roots of exaggeration postcards can be traced back to the late 1800s when photography and printing technologies were advancing rapidly. As postcards gained popularity as a means of communication, artists, and publishers began experimenting with photographic manipulation to create humorous and exaggerated depictions of everyday life. Moreover, these postcards came to function as surrogates for travel. People soon realized that postcards could be used to create or sustain a certain utopian myth about a town or region, and crafty photographers began to physically manipulate their photographs. Nowhere did these modified images, or “tall-tale postcards” as they came to be called, become more prevalent than in rural communities that hoped to forge an identity as places of agricultural abundance to encourage settlement and growth. Food sources specific to the region — vegetables, fruits, or fish — were the most common subjects. The basic process for creating a tall-tale, or “freak,” postcard is simple: a photographer would take two prints, one a background landscape and another a close-up of an object, carefully cut out the second and superimpose it onto the first, and re-shoot the combination to create a final composition. Entire businesses and studios were created for their production, such as one ran by William H. Martin. At the age of 21, Martin moved to Ottawa, Kansas to learn photography from E.H. Corwin, whose studio Martin eventually purchased a mere eight years later. In 1908, he began crafting tall-tale postcards. His exaggerated images quickly became so popular that, within a year, Martin’s company was allegedly turning out over 10,000 postcards per day. His impressive, dynamic compositions set the standard for the genre. In 1915, due to the onslaught of World War I, America banned the import of German postcards, with their diminished popularity on a national scale to follow soon after. Arguably, the aftermath of the war also fractured, for the first time, the very utopian myth upon which these postcards were based. What’s more, the advances in technology and production catalyzed by wartime industry, in the form of affordable personal automobiles and telephones, ushered in new systems of information exchange, making postcards all but obsolete. The production of exaggeration postcards slowly died out after that point, with some lasting until the 1960s. In contemporary times, exaggeration postcards have experienced a resurgence in interest and appreciation. Collectors and historians value them not only for their historical significance but also for their enduring artistic appeal. These postcards provide a unique window into the past, preserving the humor, visual aesthetics, and cultural mores of an era marked by its distinctive brand of lighthearted satire.

(Photo credit: Wisconsin Historical Society / Wikimedia Commons). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe