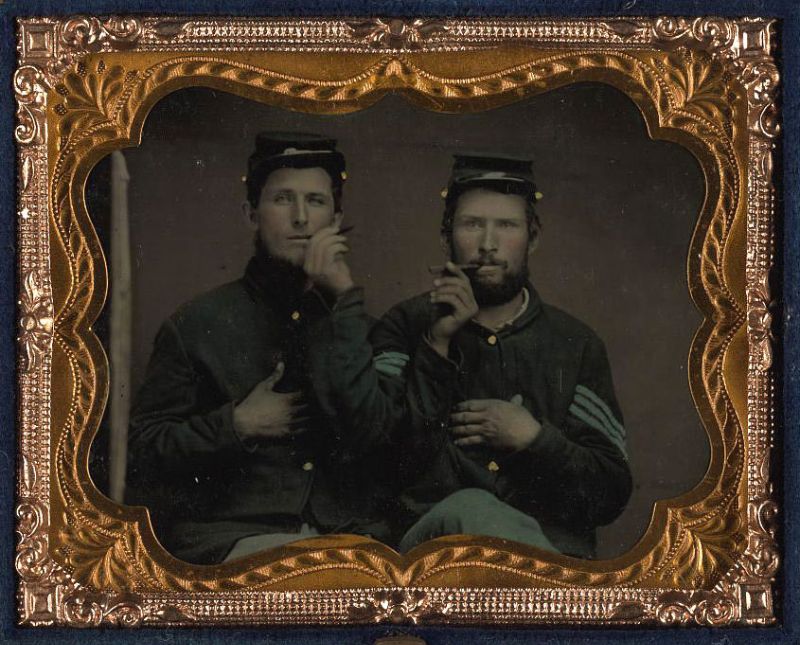

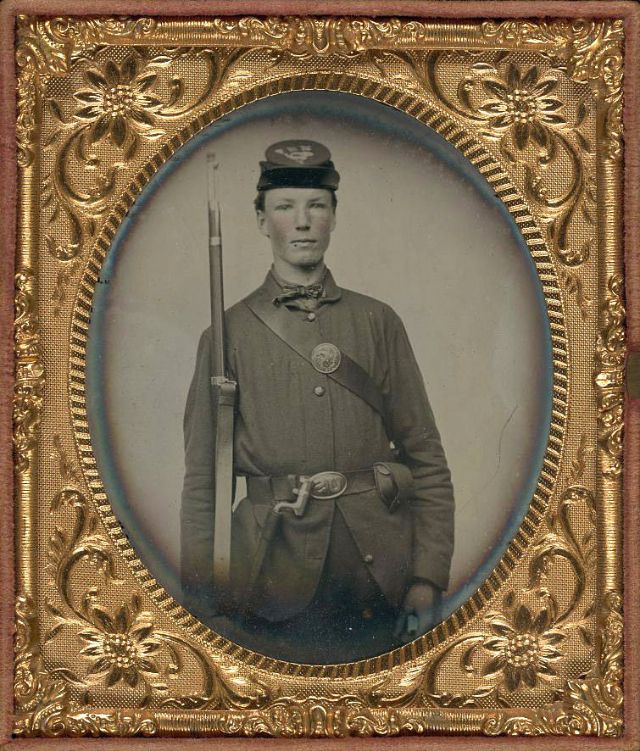

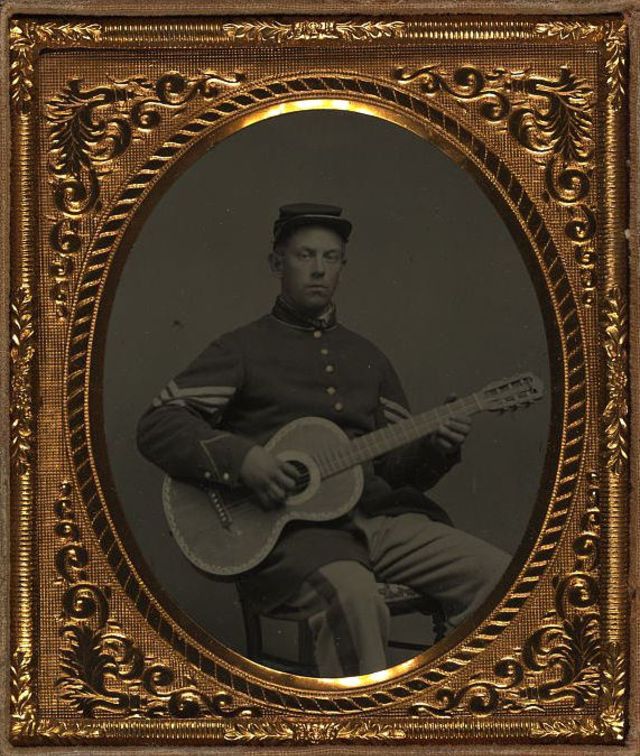

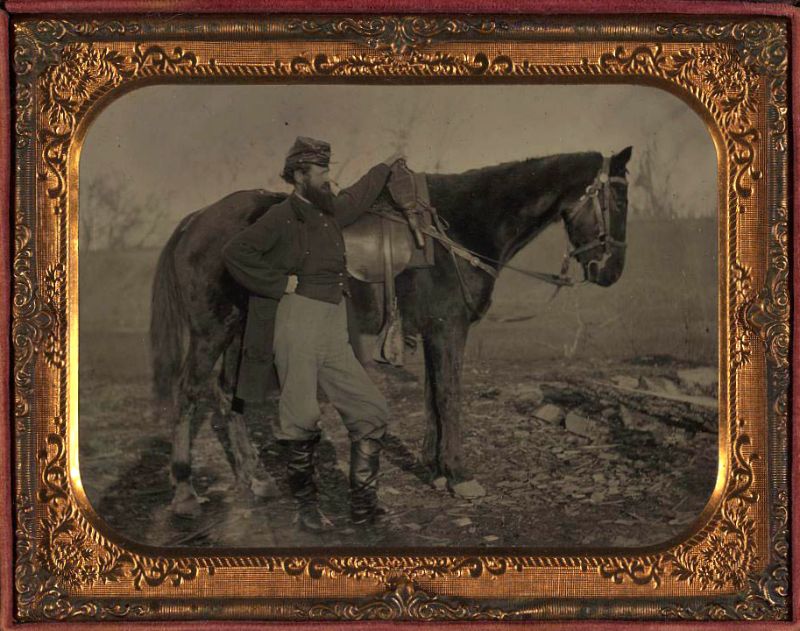

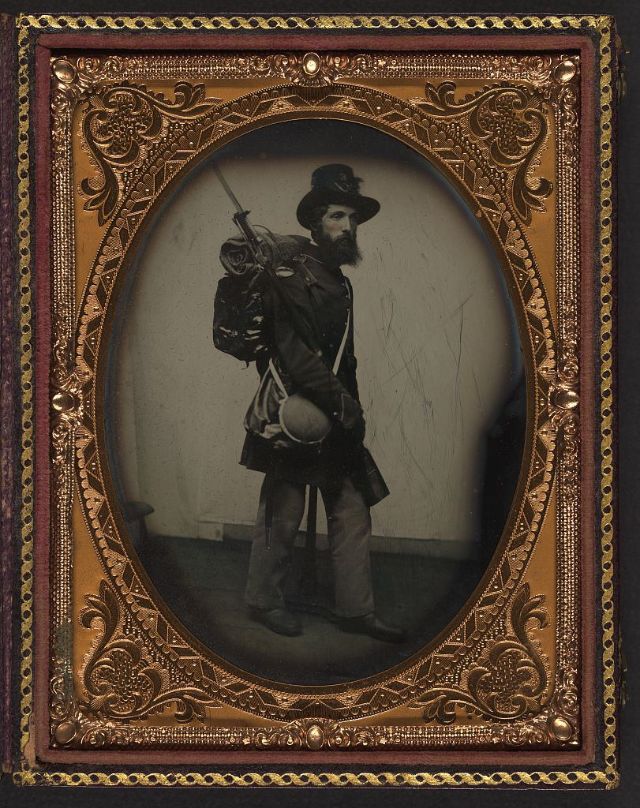

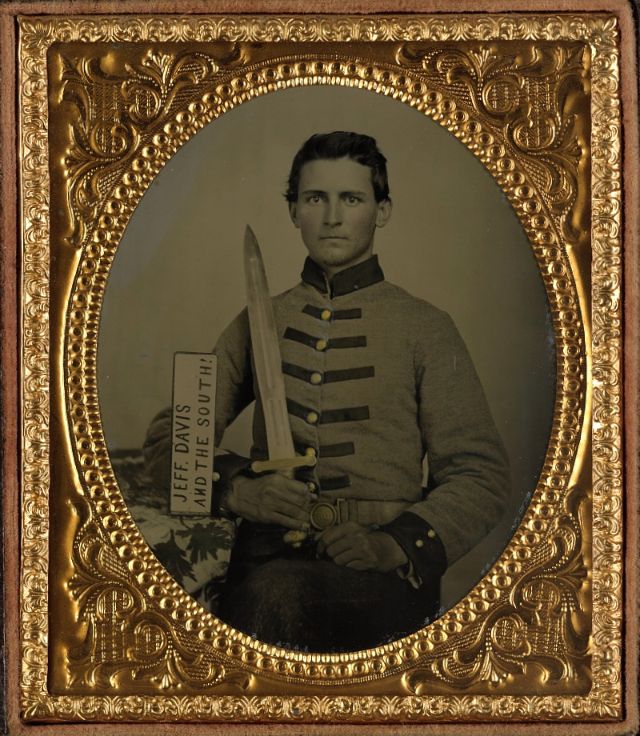

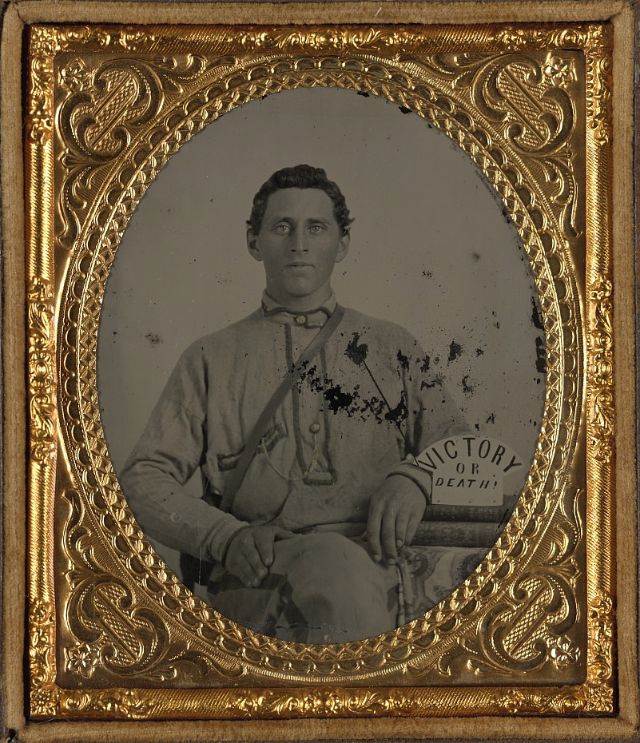

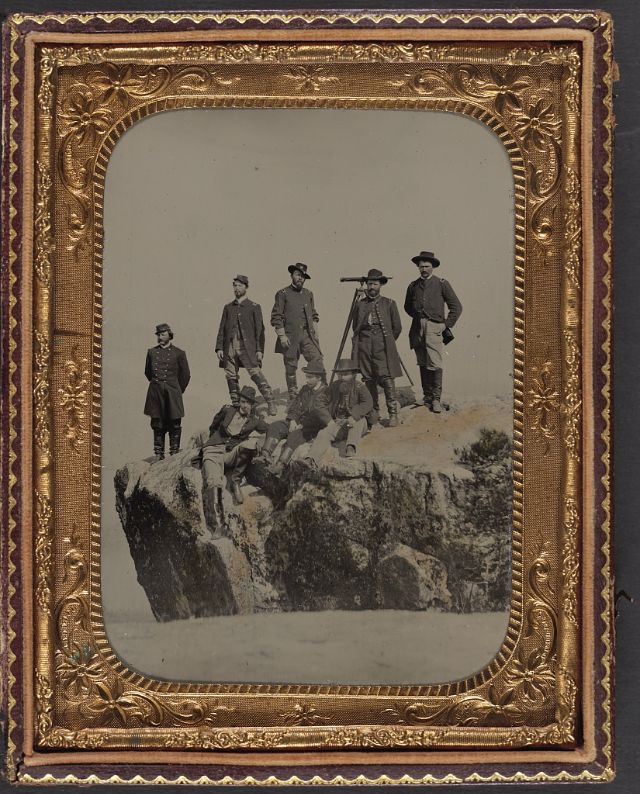

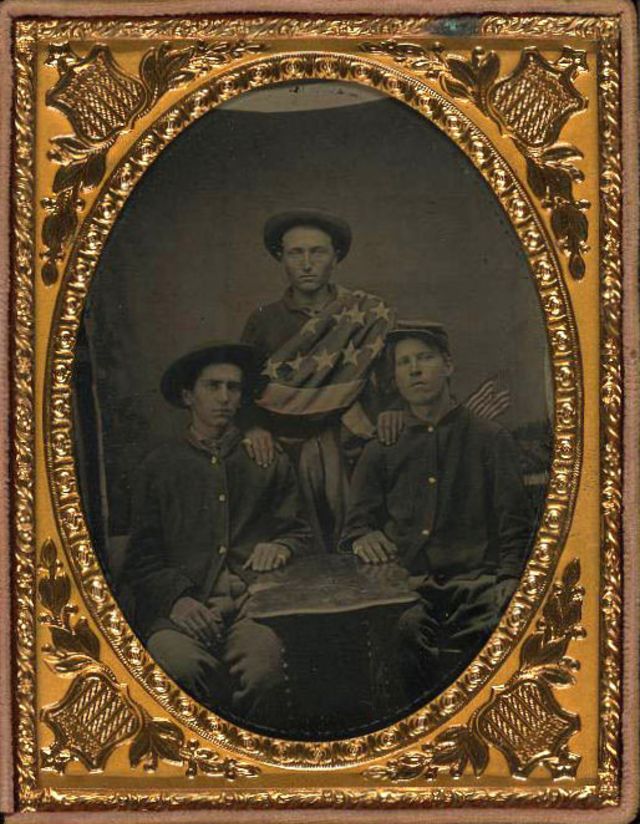

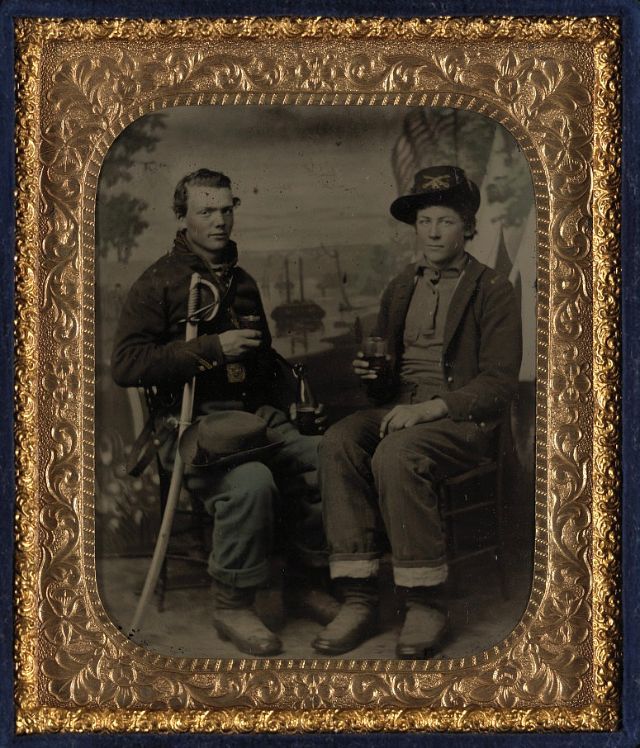

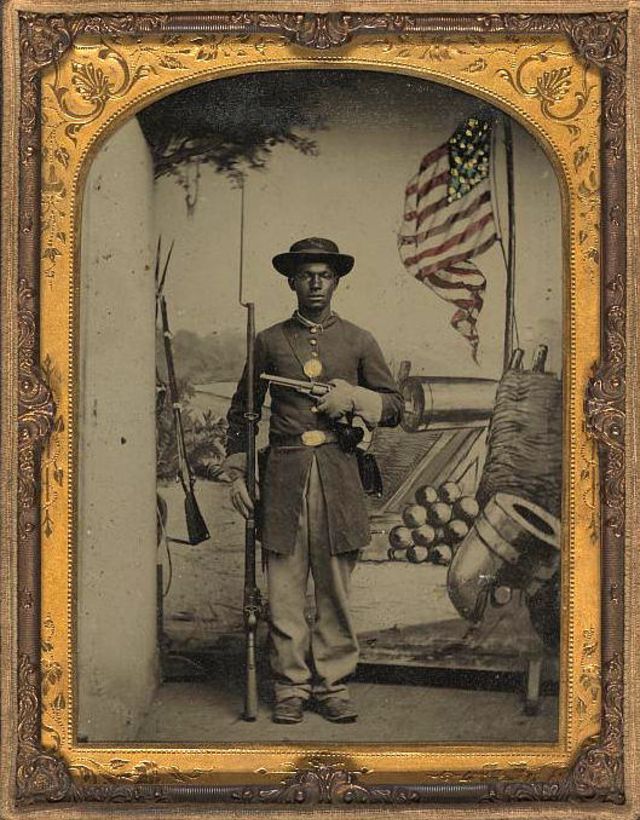

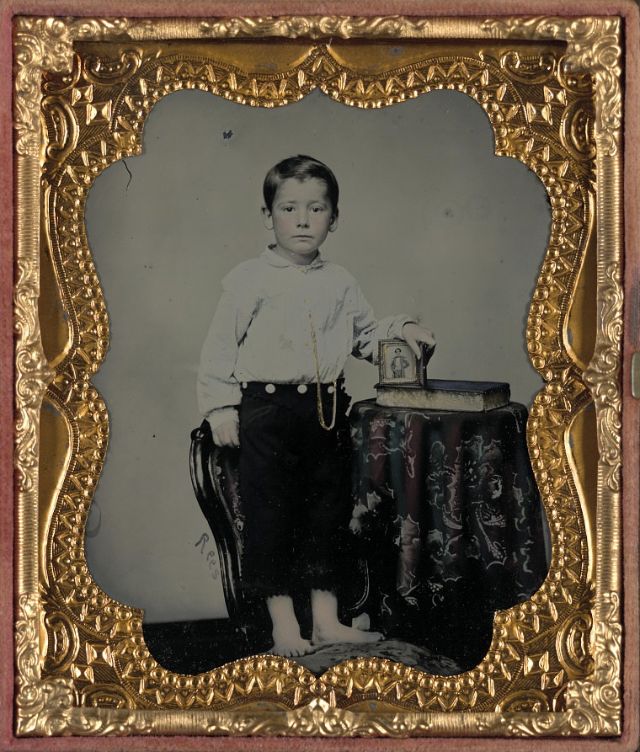

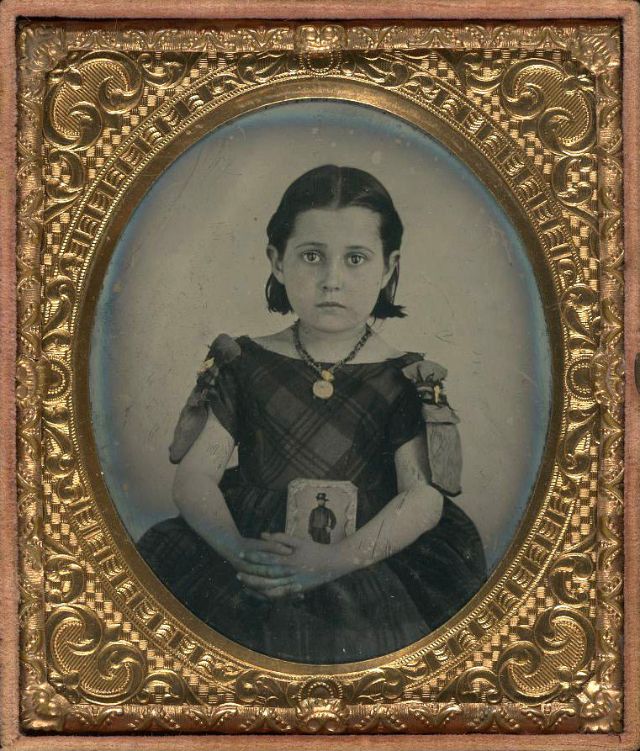

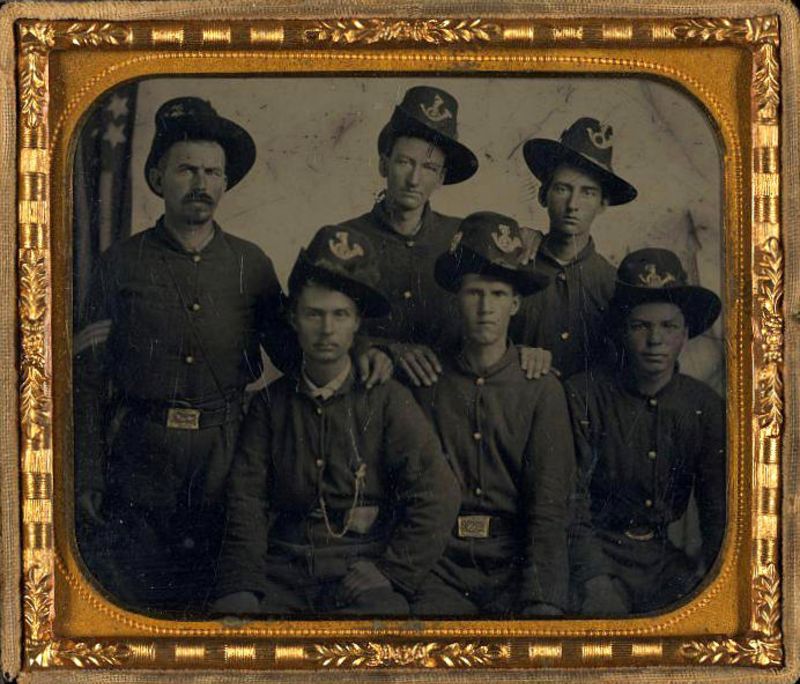

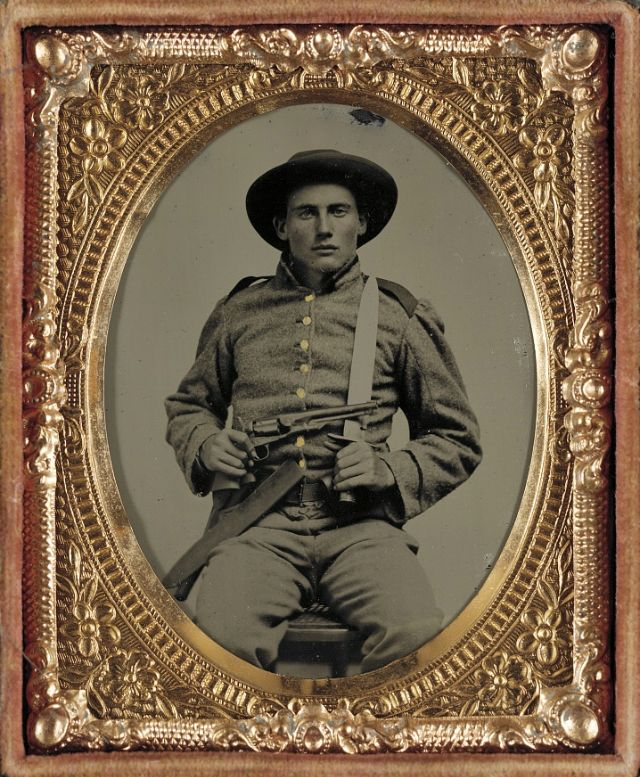

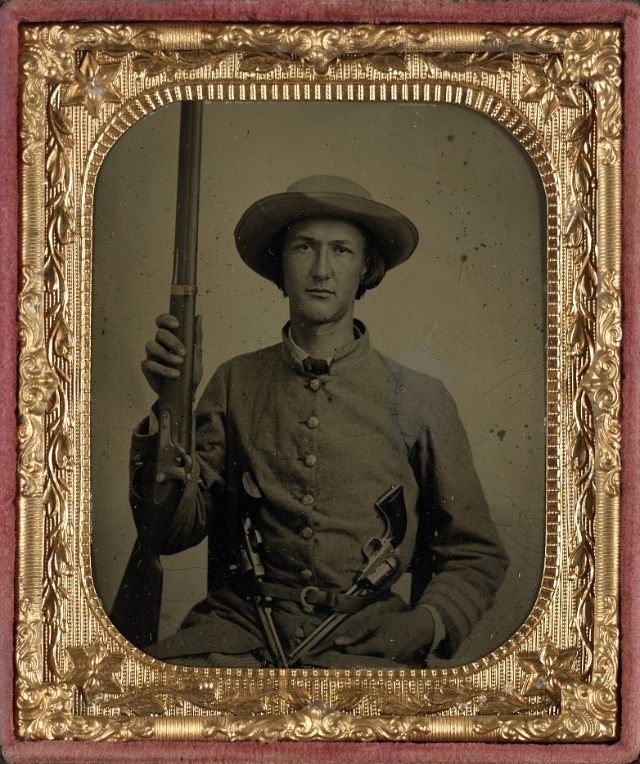

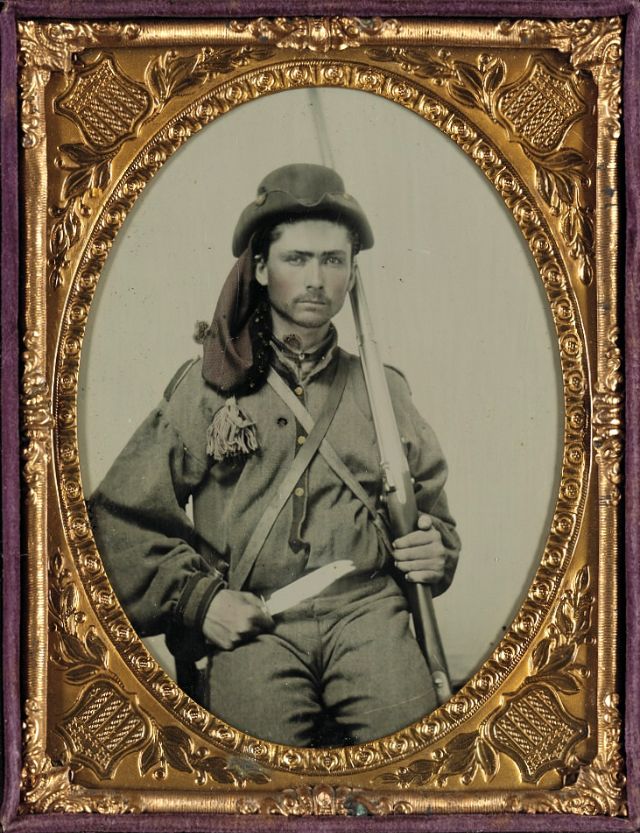

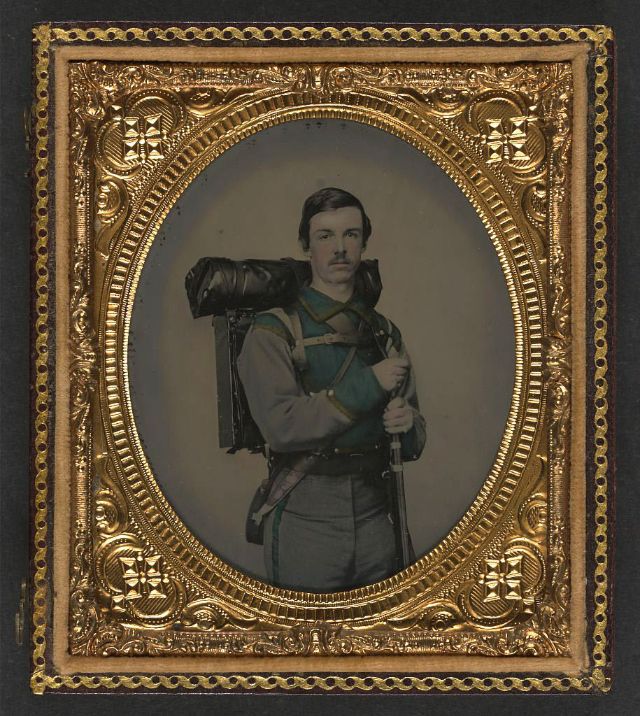

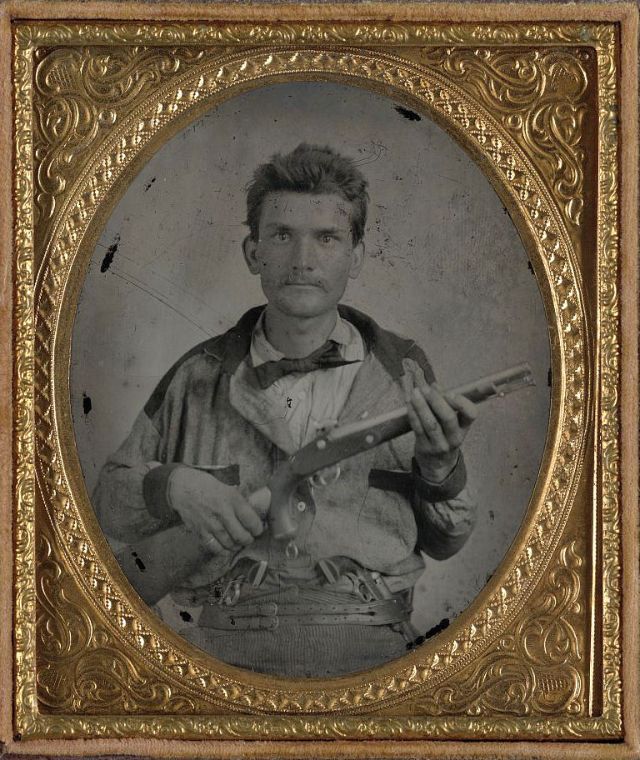

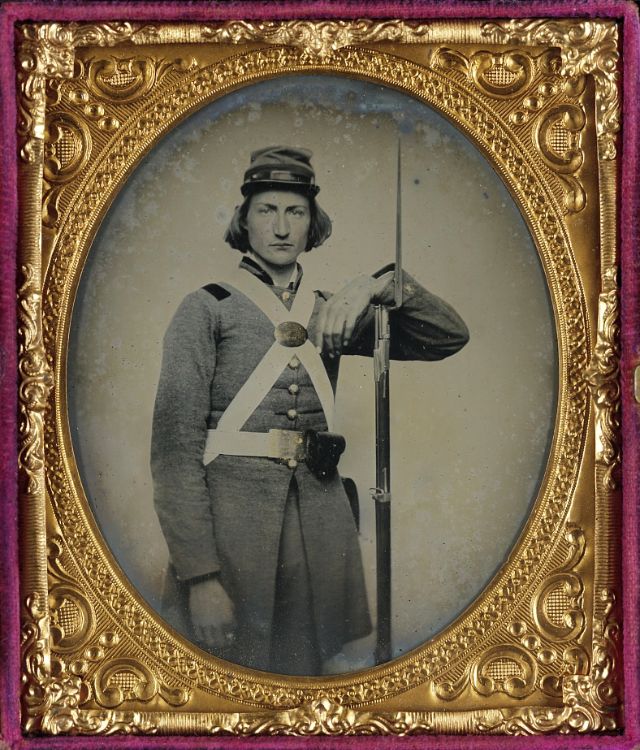

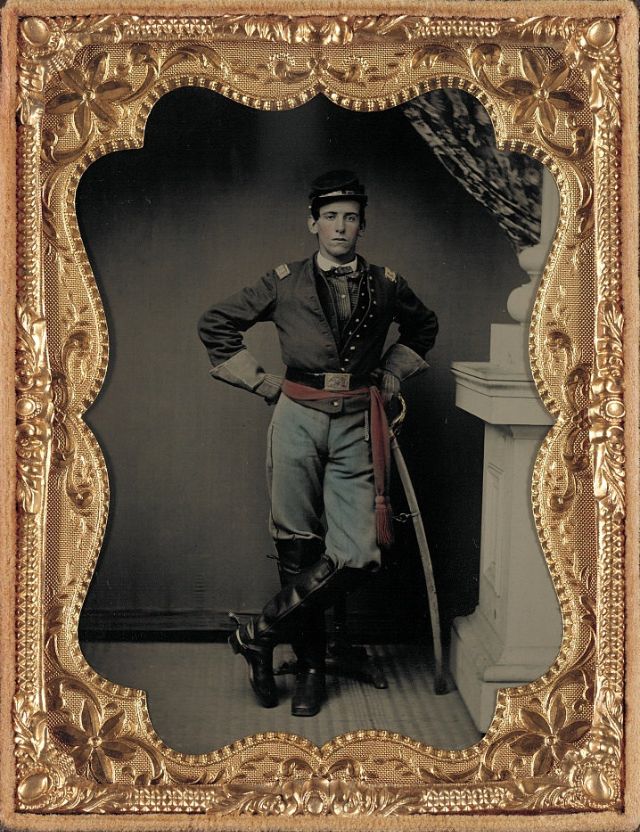

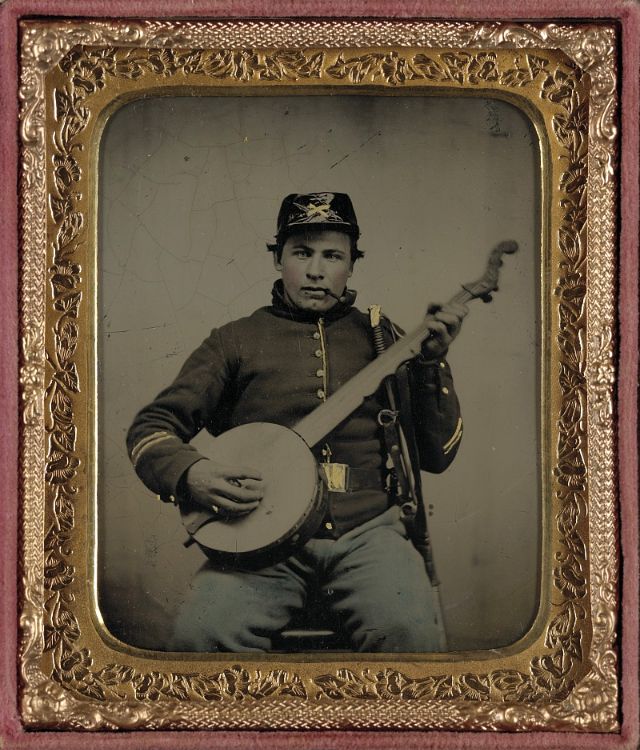

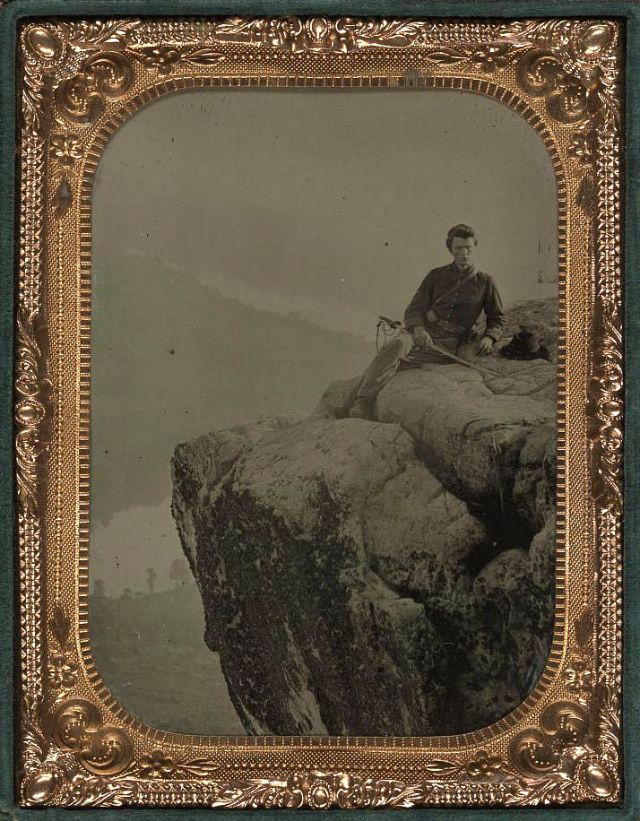

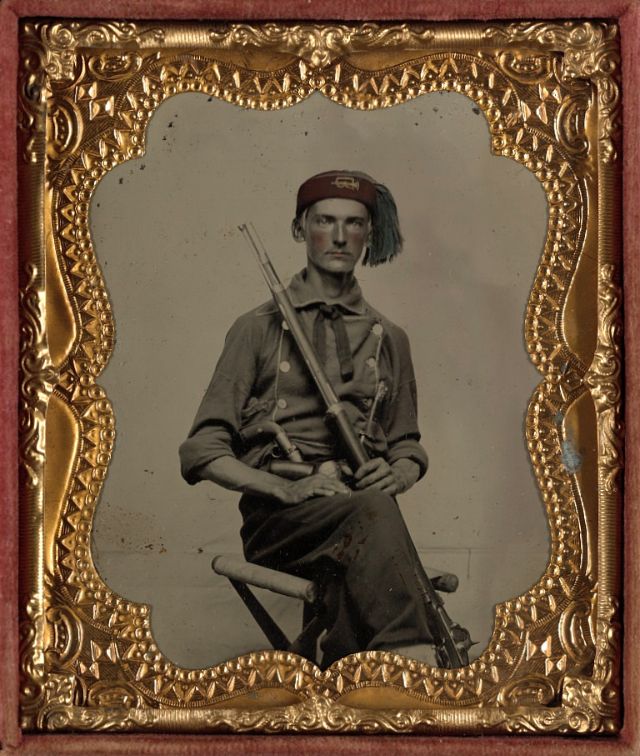

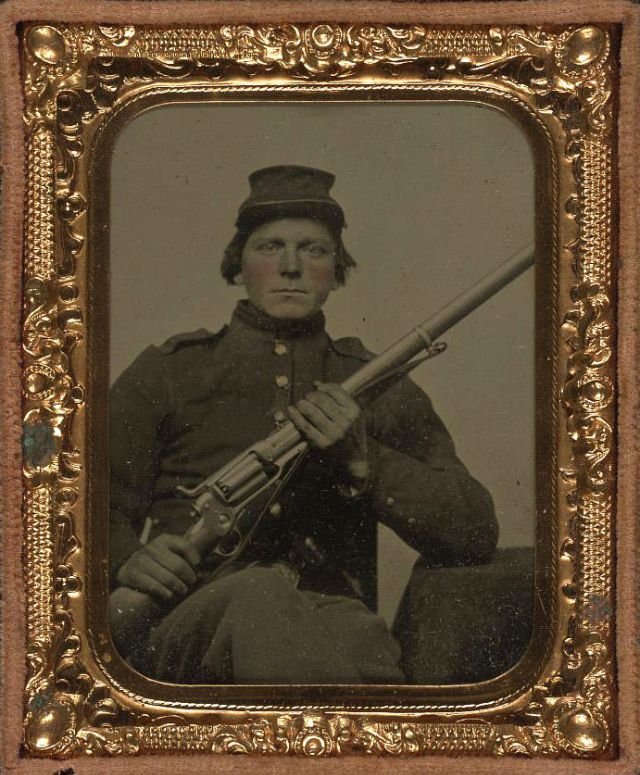

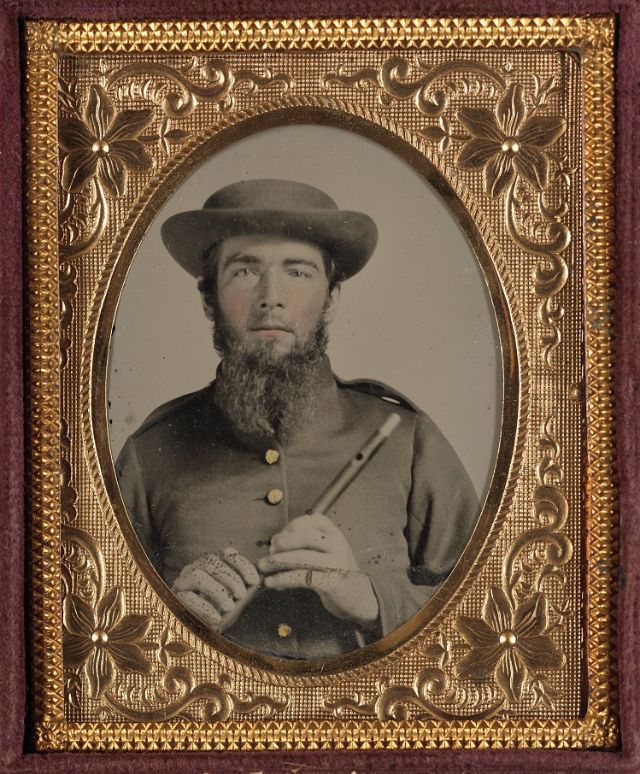

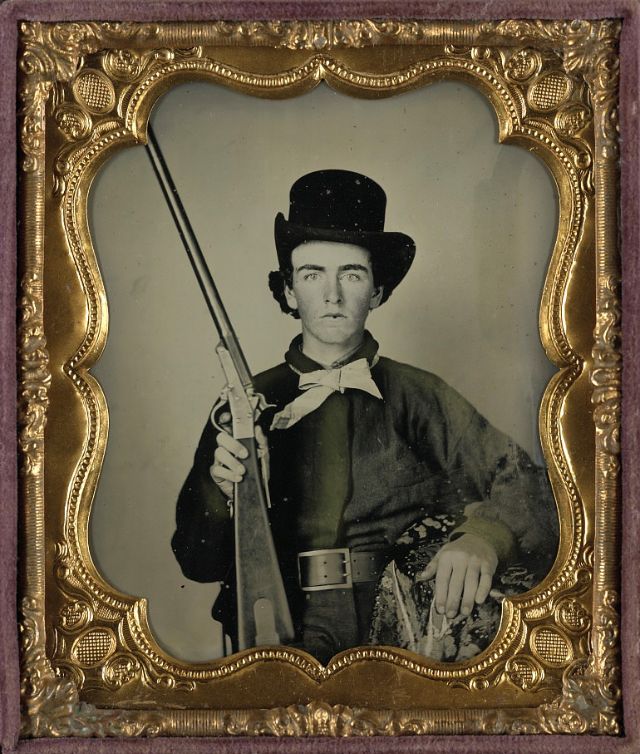

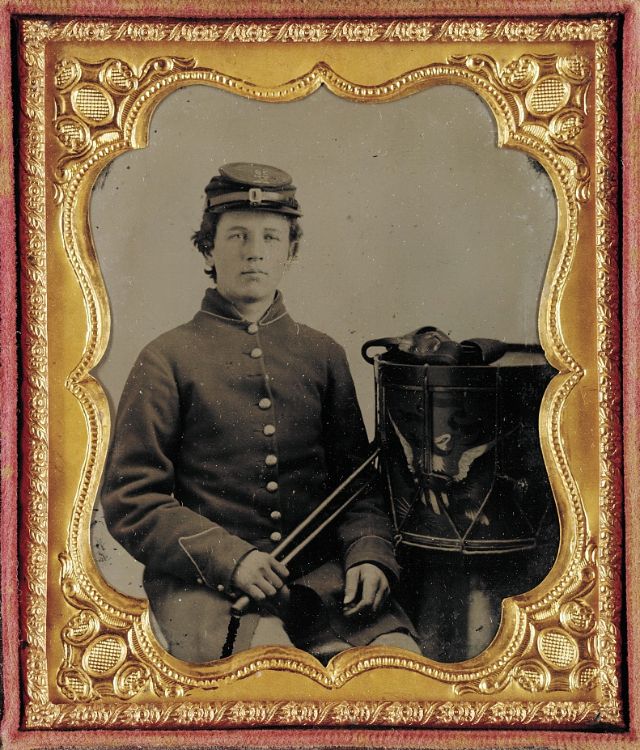

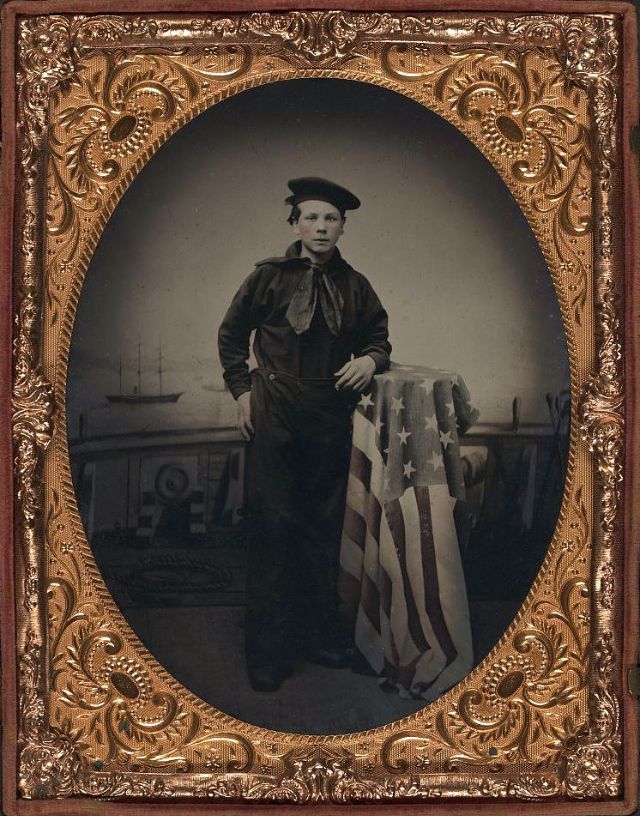

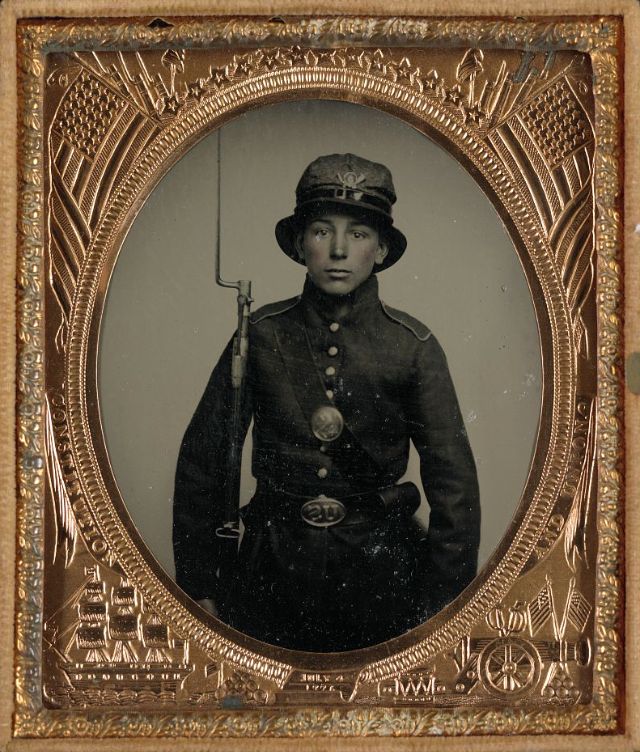

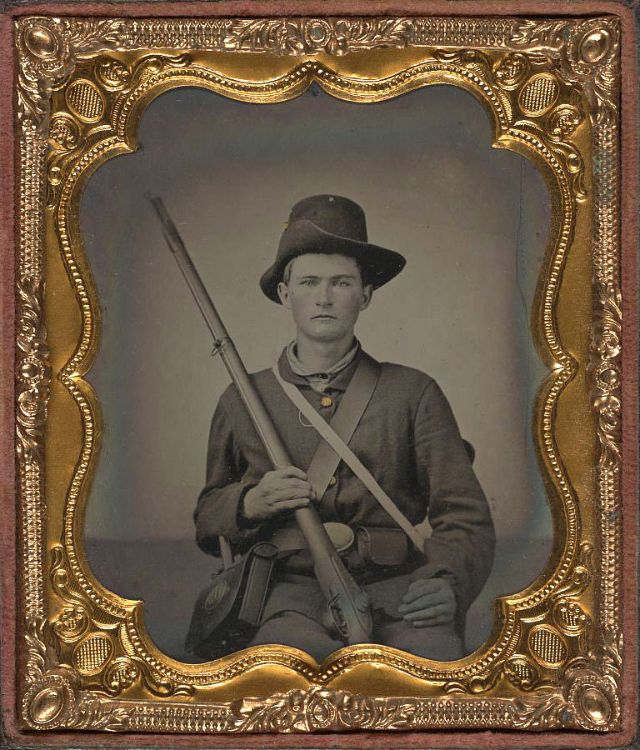

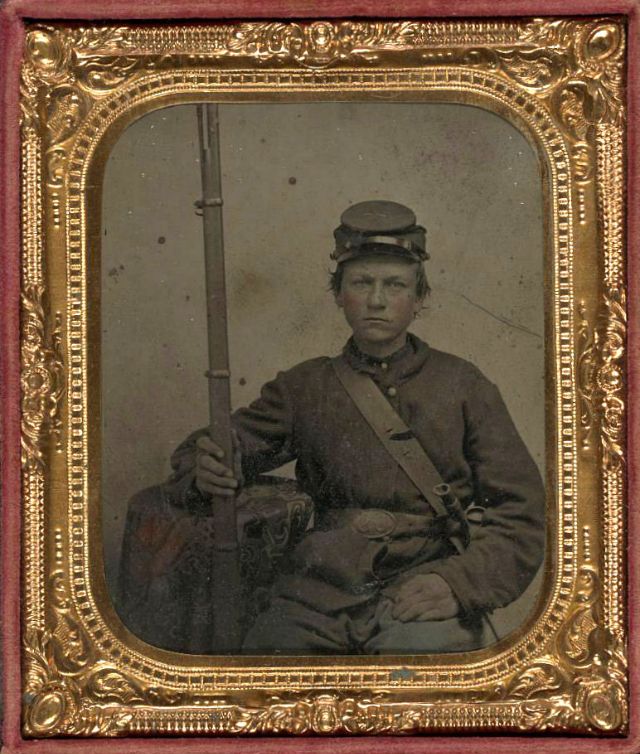

These studio portraits, captured during a pioneering era of photography, serve as enduring testaments to the lives, experiences, and roles of those who took part in this historic conflict. The mid-19th century marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of photography. The daguerreotype, introduced in 1839, was the earliest photographic process, but it required subjects to sit still for several minutes, resulting in a single, unique image on a polished metal plate. As photographic techniques advanced, the ambrotype and tintype processes allowed for quicker and more affordable portraiture. Soldiers cherished these portraits as tokens of affection for their families and loved ones. Encased in ornate holders, these images provided comfort and a connection to their homes during the hardships of war. In many instances, they adorned themselves with items representative of their trades, carried weapons, or displayed cherished mementos, revealing unique facets of their experiences and backgrounds. Preserved in archives, museums, and private collections, these portraits connect us to the faces and stories of those who lived through one of the most transformative periods in American history. The war resulted in at least 1,030,000 casualties (3 percent of the population), including about 620,000 soldier deaths—two-thirds by disease—and 50,000 civilians. Binghamton University historian J. David Hacker believes the number of soldier deaths was approximately 750,000, 20 percent higher than traditionally estimated, and possibly as high as 850,000. A novel way of calculating casualties by looking at the deviation of the death rate of men of fighting age from the norm through analysis of census data found that at least 627,000 and at most 888,000 people, but most likely 761,000 people, died in the war. As historian McPherson notes, the war’s “cost in American lives was as great as in all of the nation’s other wars combined through Vietnam.” (Photo credit: Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe