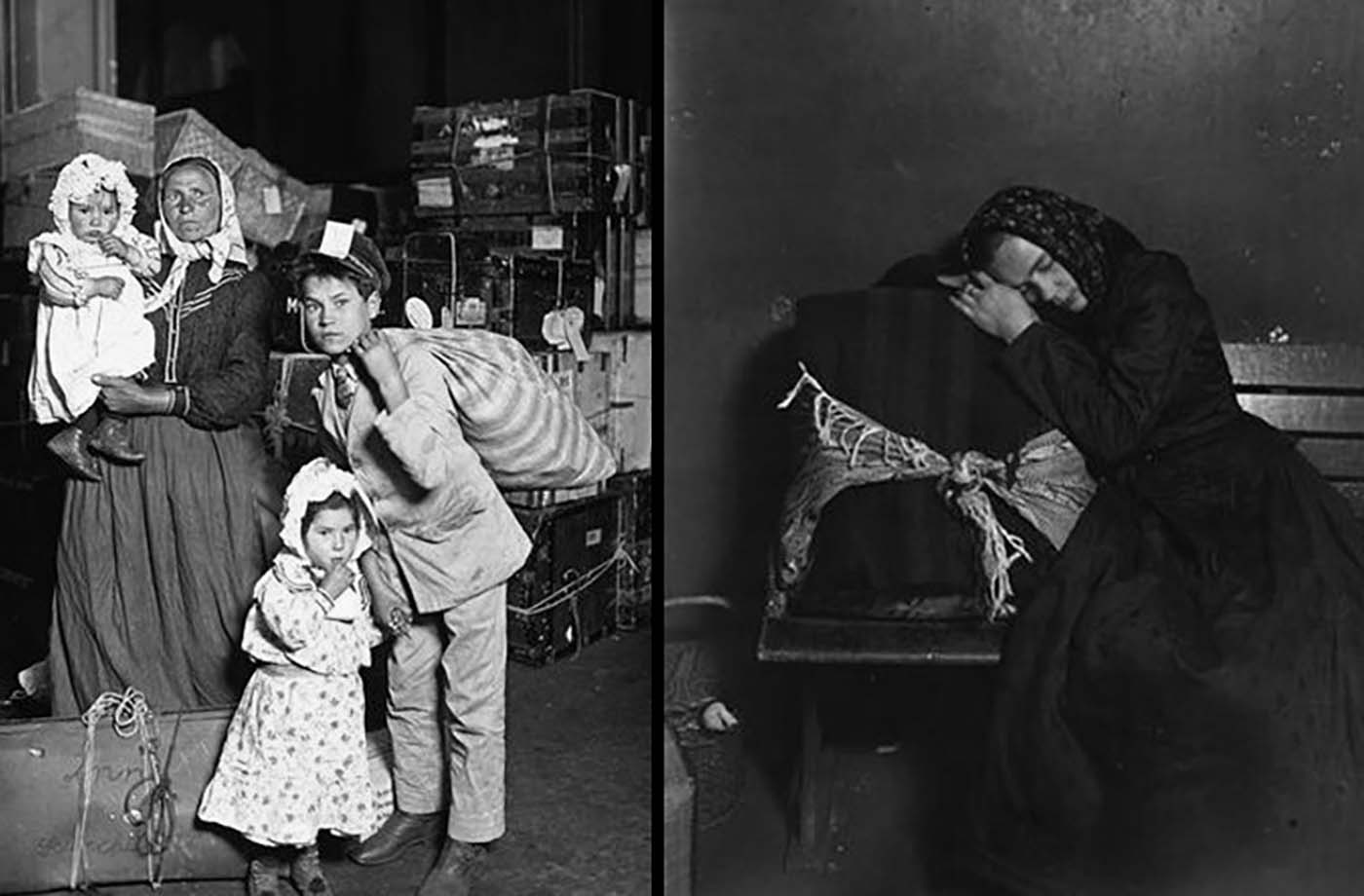

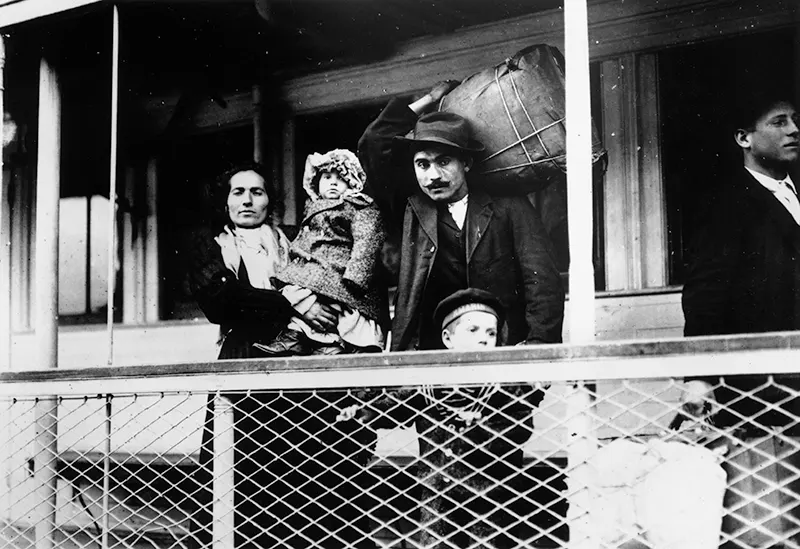

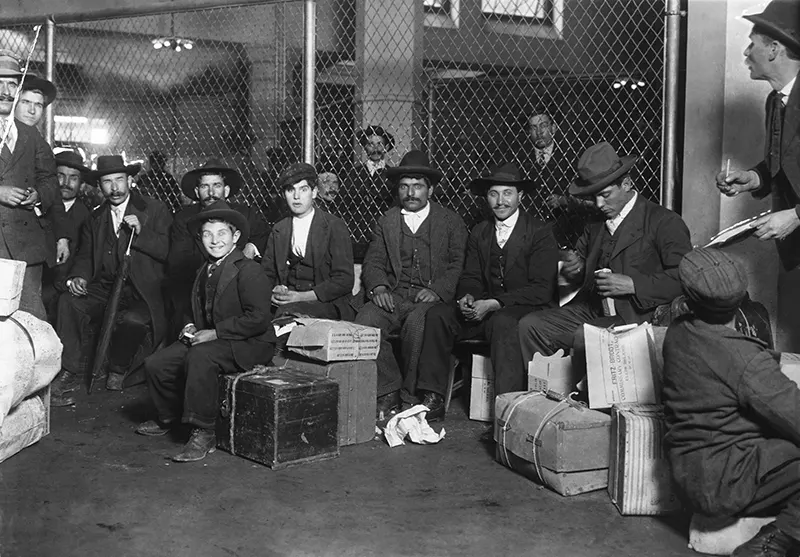

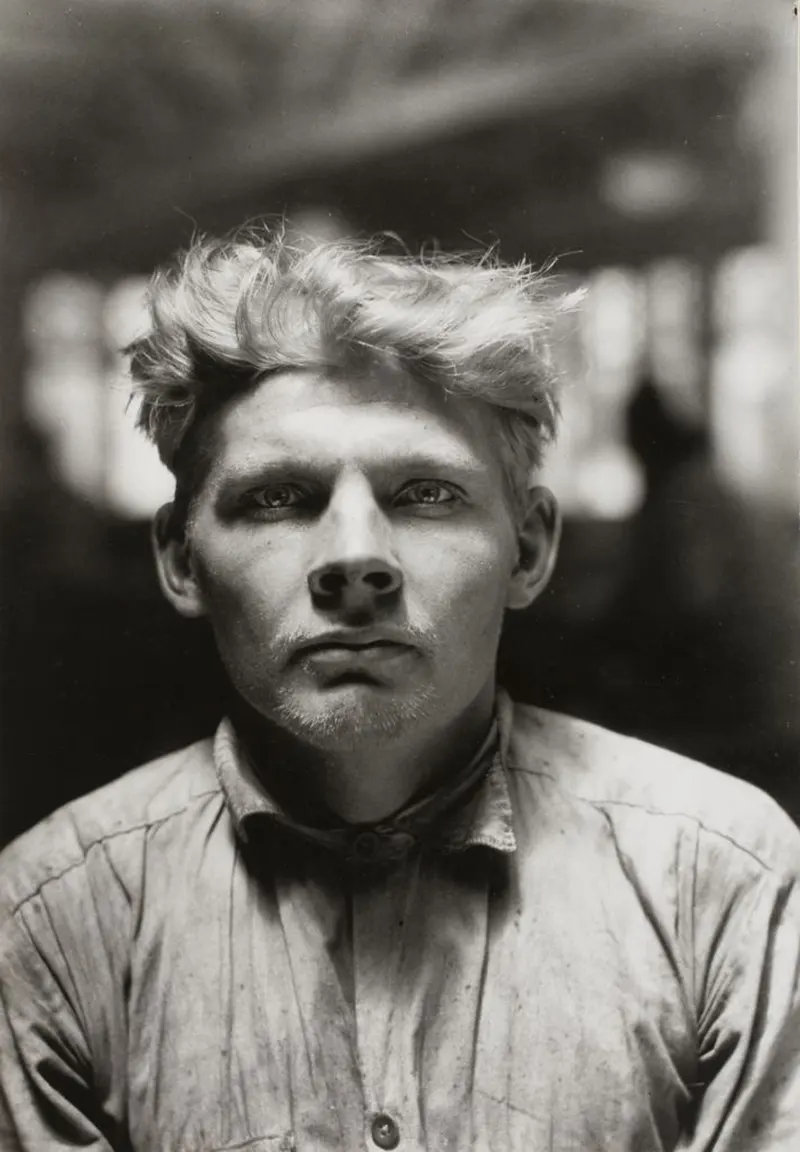

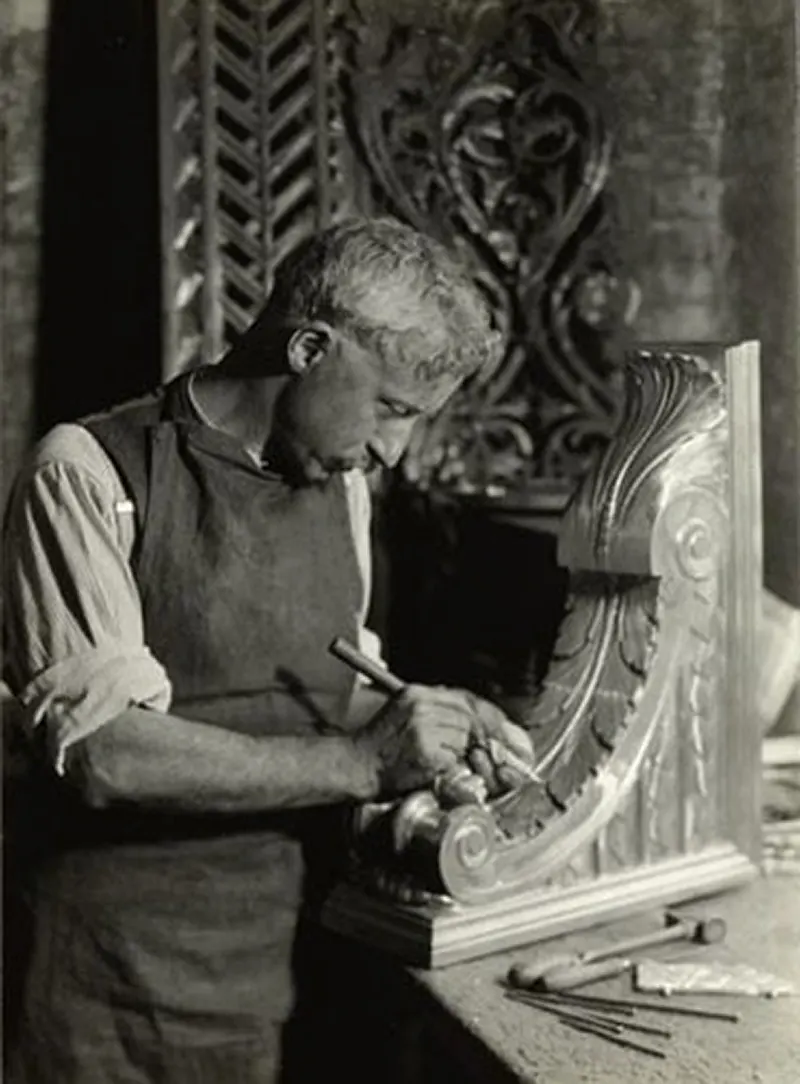

Between 1820 and 1920, approximately 34 million immigrants came to this country, and New York City was by the far the most popular destination. By 1910, immigrants and their American-born children accounted for more than 70 percent of New York City’s population. As steamships sailed to Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty greeted them, her inscription calling out, “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Unlike earlier immigrants, the majority of the newcomers after 1900 came from non-English-speaking European countries. The principal source of immigrants was now southern and eastern Europe, especially Italy, Poland, and Russia, countries quite different in culture and language from the United States, and many immigrants had difficulty adjusting to life here. At the same time, the United States had difficulty absorbing the immigrants. Most of the immigrants chose to settle in American cities, where jobs were located. As a result, the cities became ever more crowded. In addition, city services often failed to keep up with the flow of newcomers. Most of the immigrants did find jobs, although they often worked in jobs that most native-born Americans would not take. Over time, however, many immigrants succeeded in improving their conditions. From 1892 to 1924, Ellis Island was America’s largest and most active immigration station, where over 12 million immigrants were processed. On average, the inspection process took approximately 3-7 hours. For the vast majority of immigrants, Ellis Island truly was an “Island of Hope” – the first stop on their way to new opportunities and experiences in America. For the rest, it became the “Island of Tears” – a place where families were separated and individuals were denied entry into the United States. New arrivals were processed quickly. In the Registry Room, Public Health Service doctors looked to see if any of them wheezed, coughed, shuffled or limped. Children were asked their names to make sure they weren’t deaf or dumb. Toddlers were taken from their mothers’ arms and made to walk. As the line moved forward, doctors had only a few seconds to check each immigrant for sixty symptoms of disease. Of primary concern were cholera, favus (scalp and nail fungus), tuberculosis, insanity, epilepsy, and mental impairments. The disease most feared was trachoma, a highly contagious eye infection that could lead to blindness and death. Once registered, immigrants were free to enter the New World and start their new lives. But if they were sick, they spent days, weeks, months even, in a warren of rooms. Some, like the tuberculosis ward, were open to the sea, where a gentle New York harbor breeze cleansed their lungs, improving their chances. Other rooms were solitary, forlorn places where the illness itself decided when to leave or stay. Most patients in the hospital or Contagious Disease Ward recovered, but some were not so lucky. More than 120,000 immigrants were sent back to their countries of origin, and during the island’s half-century of operation more than 3,500 immigrants died there. Ellis Island waylaid certain arrivals, including those likely to become public charges, such as unescorted women and children. Women could not leave Ellis Island with a man not related to them. Other detainees included stowaways, alien seamen, anarchists, Bolsheviks, criminals and those judged to be “immoral.” Approximately 20 percent of immigrants inspected at Ellis Island were temporarily detained, half for health reasons and half for legal reasons (Photo by Lewis W. Hine / Library of Congress / The New York Public Library / Wikimedia Commons / NPS). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe