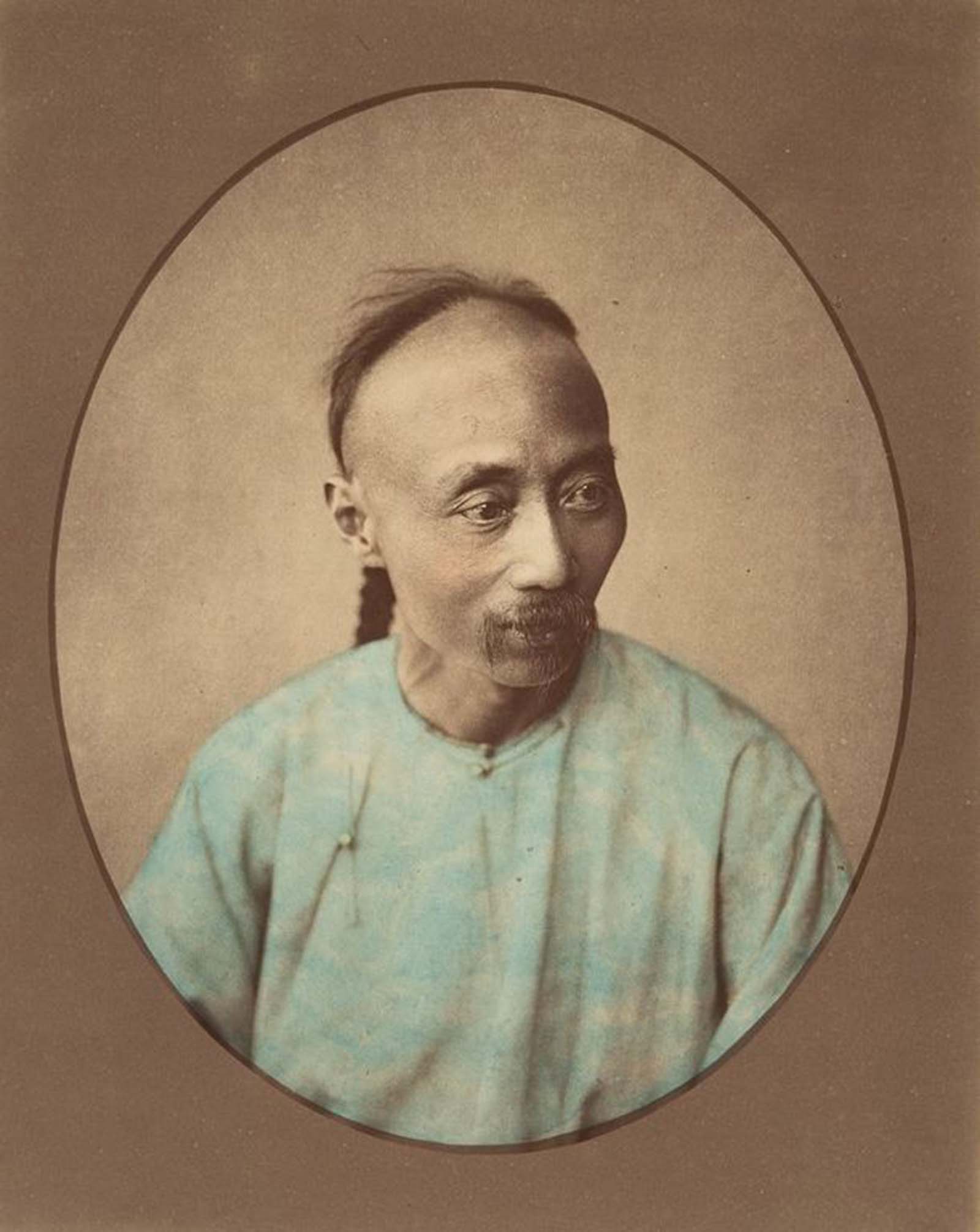

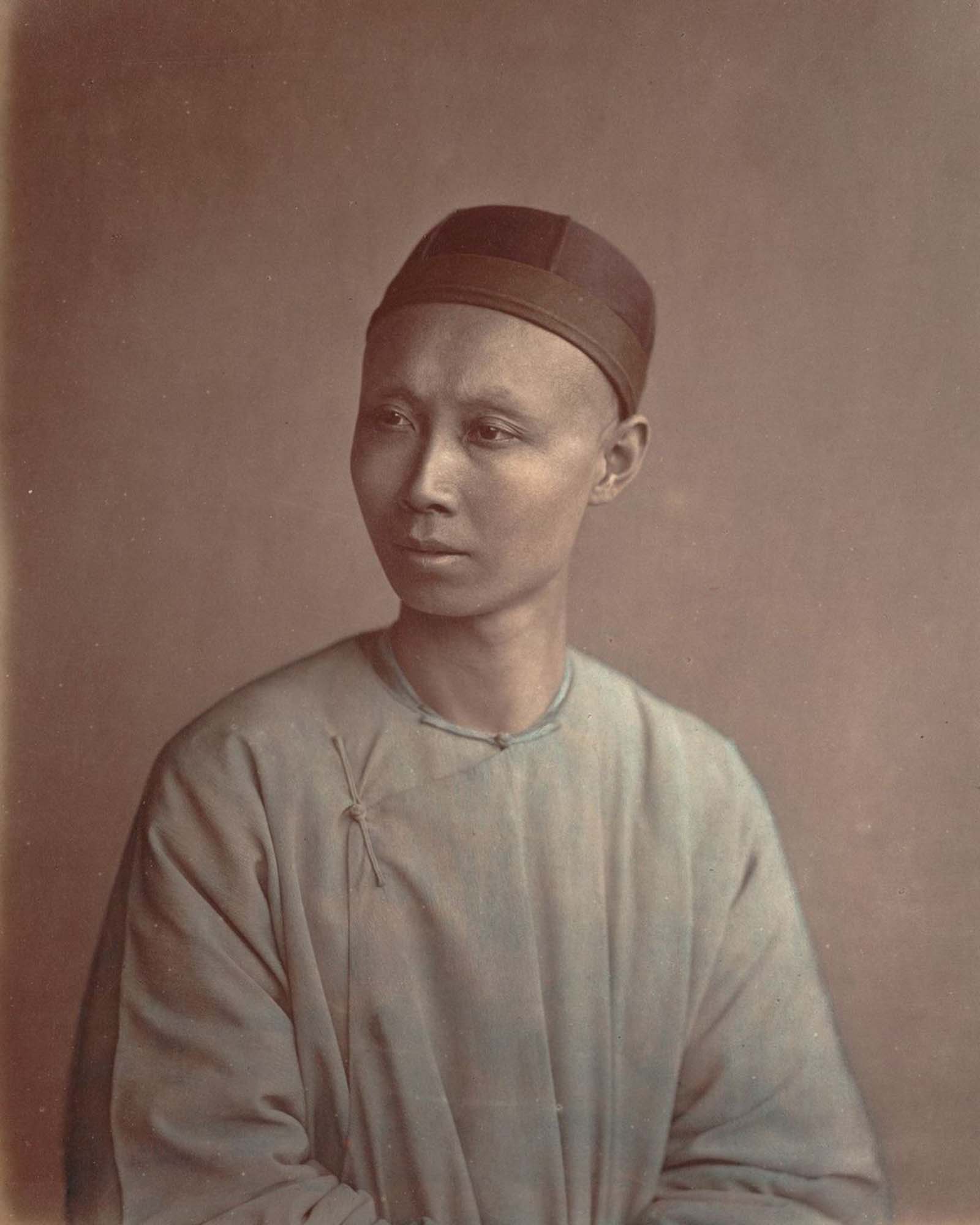

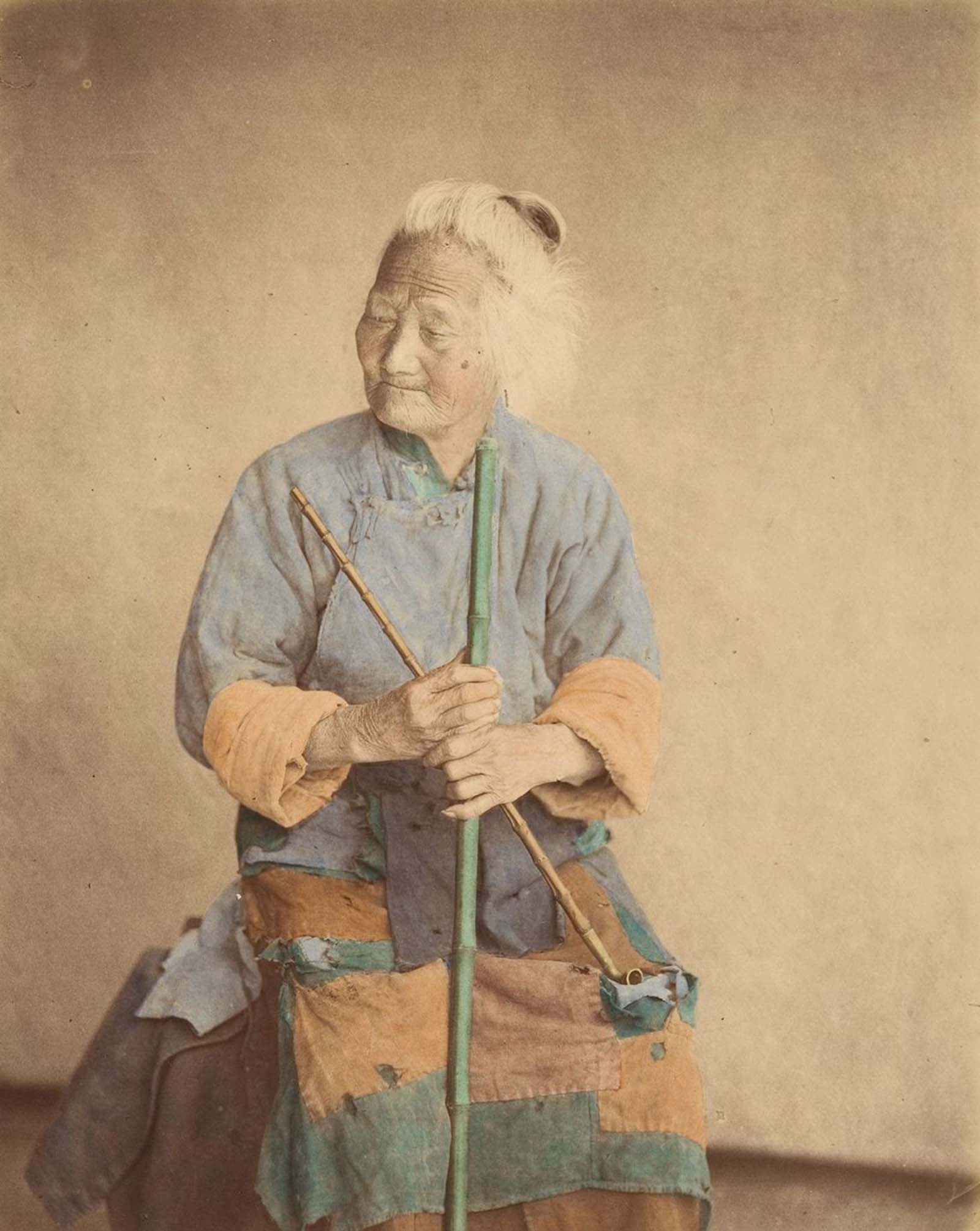

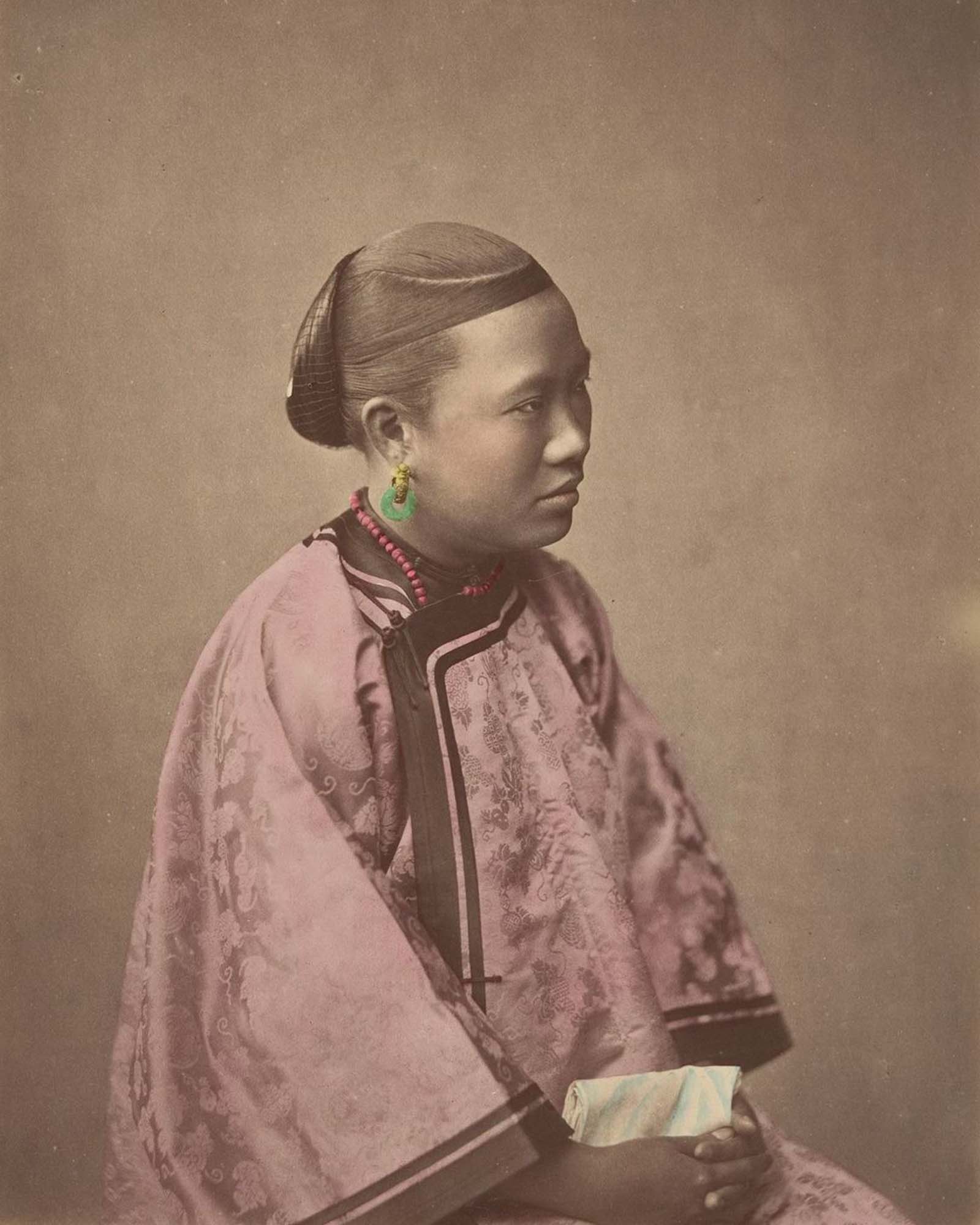

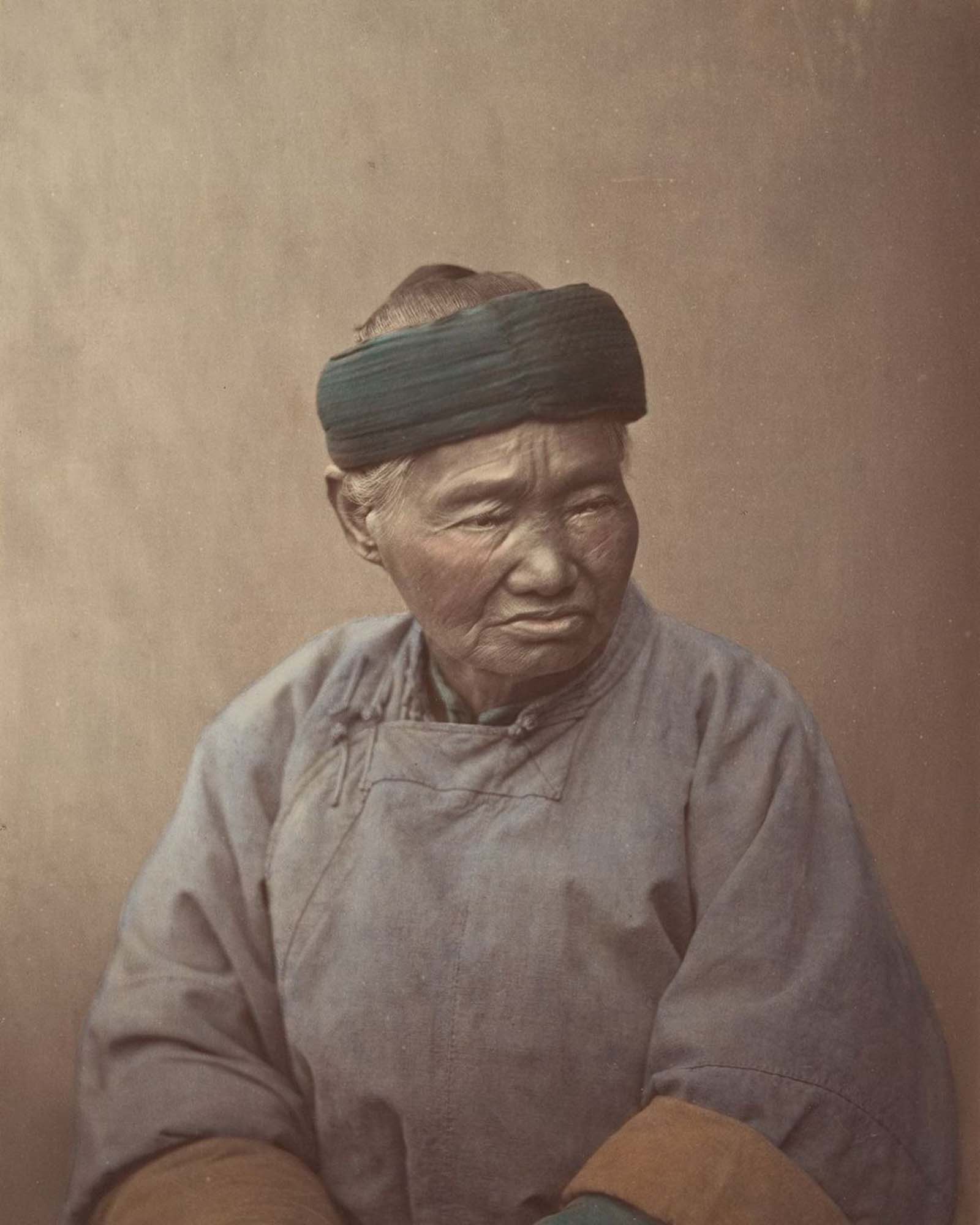

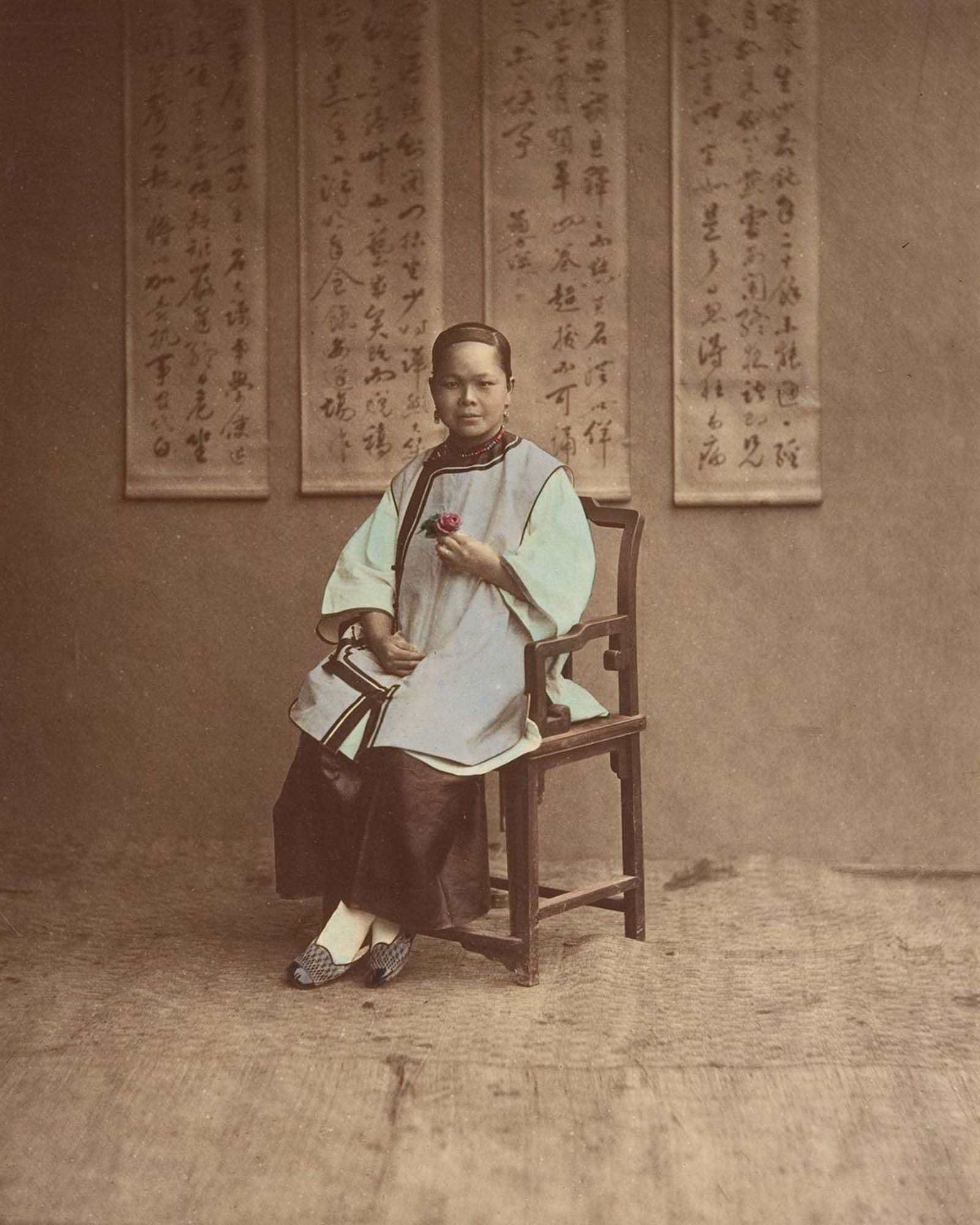

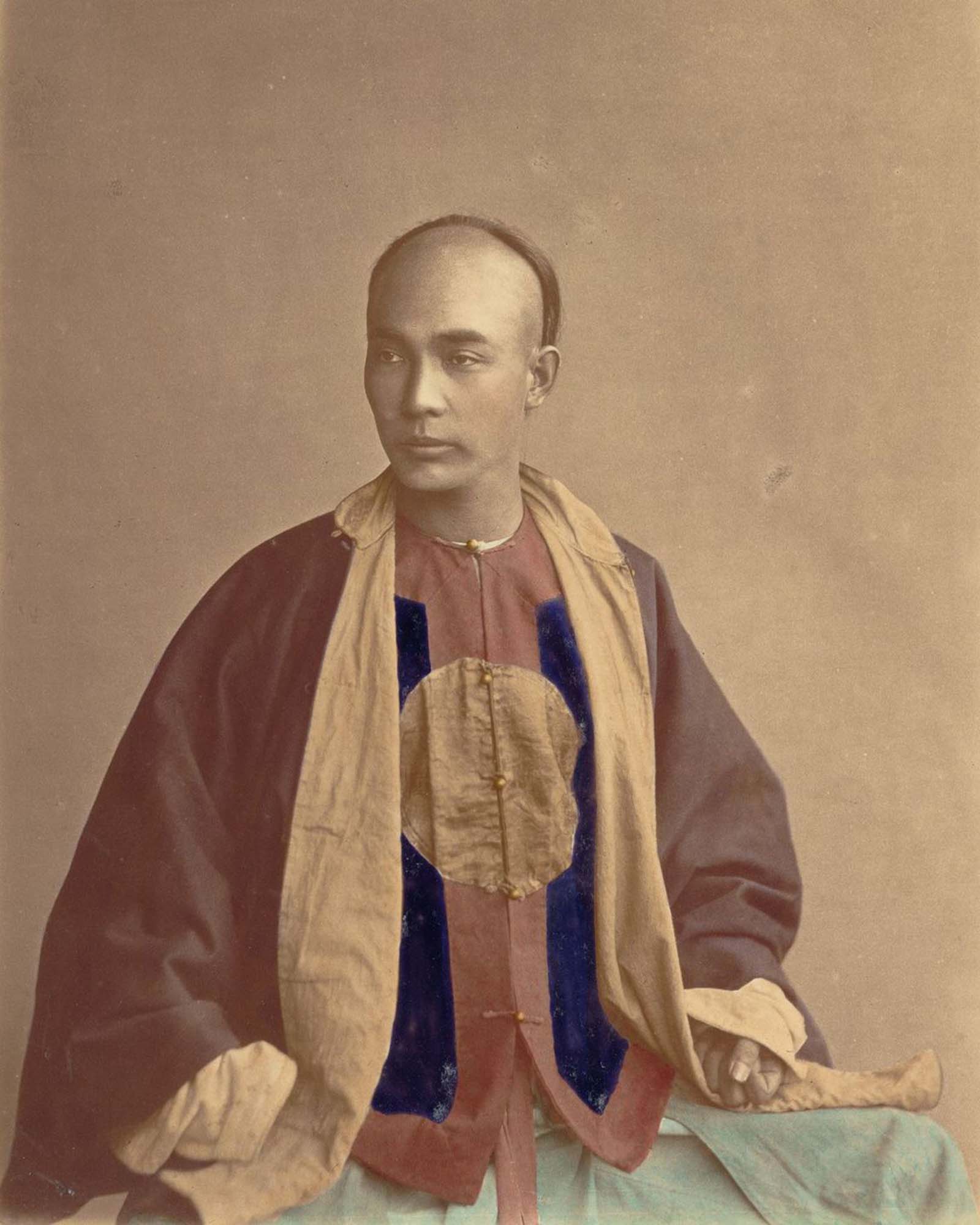

While studying at the Imperial Marine Academy in Trieste, and then the Imperial Military Engineering School in Tulln, Austria, he began to pursue painting. Although his military career with the Austro-Hungarian Empire was short-lived, lasting only from 1859 to 1863, the lure of the seas and far-flung places inspired by his naval education and his Orientalist painting teachers led him to South America, China, and then Japan, which he reached in 1864. For the 1873 Vienna World Exposition, the government of Japan commissioned Stillfried to travel to Hokkaido, where he took photographs documenting the process of the country’s modernization, as well as of ethnic Ainu people. According to a review of a monographic book on his life and work, “Stillfried came to Japan just as it was opening to trade, tourism, and Western influences. And with the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate, the new imperial government was figuring out how best to represent itself as a modern nation through photography, and Stillfried was well-positioned to assist.” In the mid-1870s, Stillfried traveled to Shanghai and applied the same aesthetic conventions to traditional Chinese “types,” posing beggars, workers, and high society people in carefully staged portraits. These hand-colored souvenir photos were meant for wealthy Western tourists to bring home. Nineteenth-century China faced enormous problems, many of them resulting from an escalating population. By the mid-nineteenth century, China’s population reached 450 million or more, more than three times the level in 1500. The inevitable results were land shortages, famine, and an increasingly impoverished rural population. Heavy taxes, inflation, and greedy local officials further worsened the farmer’s situation. Meanwhile, the government neglected public works and the military, and as bureaucratic efficiency declined, landowners, secret societies, and military strongmen took over local affairs. Rebellion, lawlessness, and foreign exploitation continued to plague the Qing regime until the Revolution of 1911 ended China’s imperial tradition.

(Photo credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe