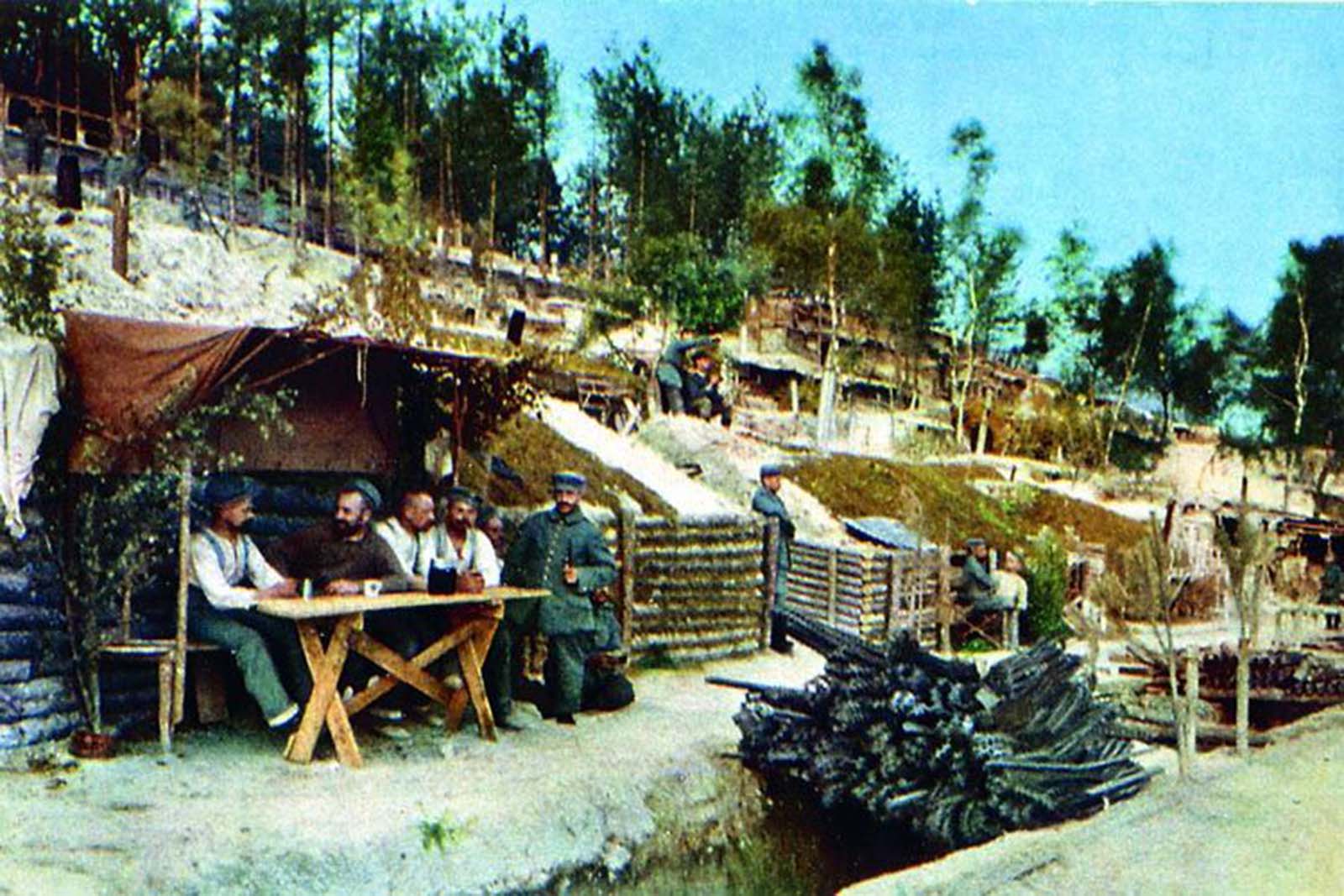

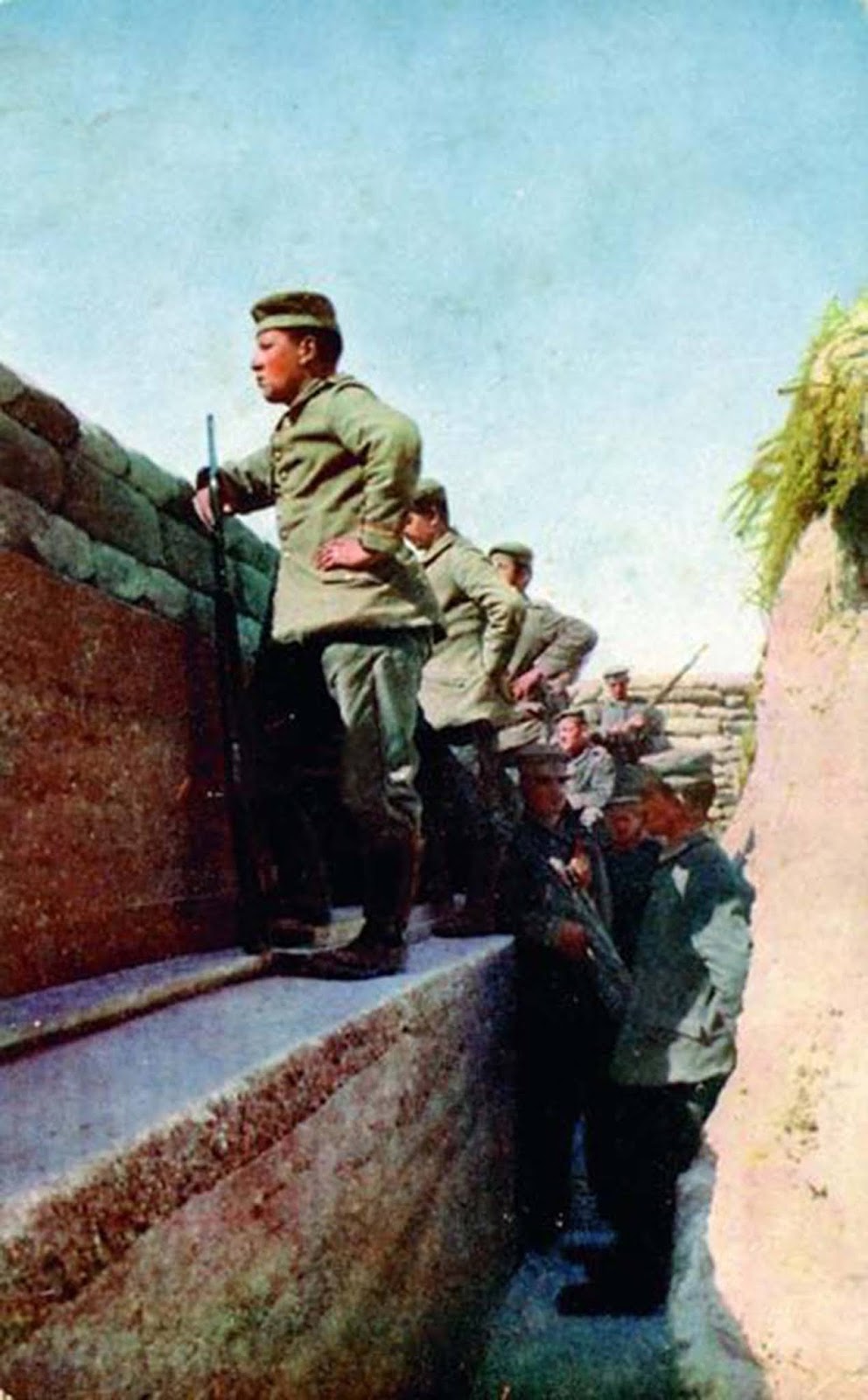

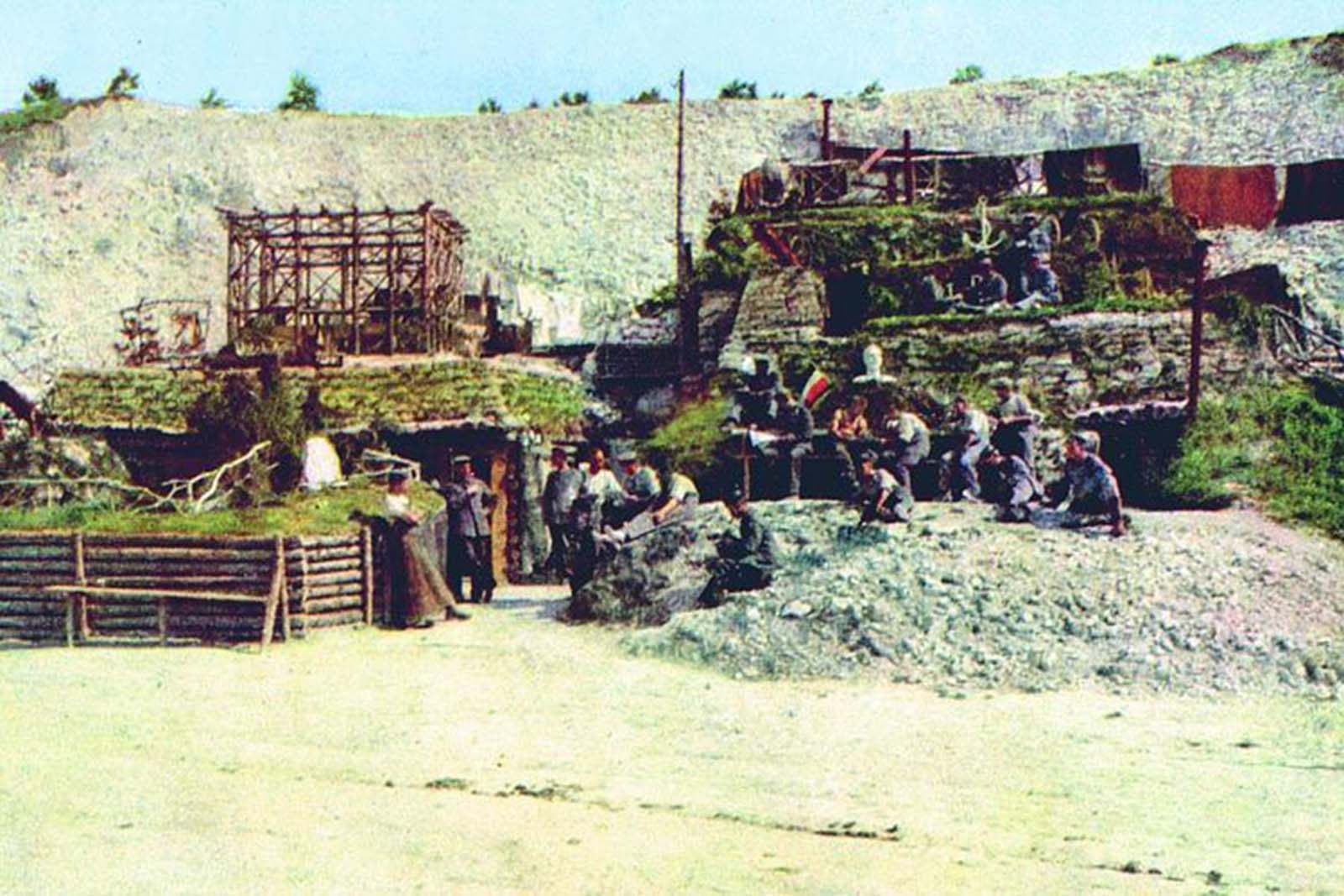

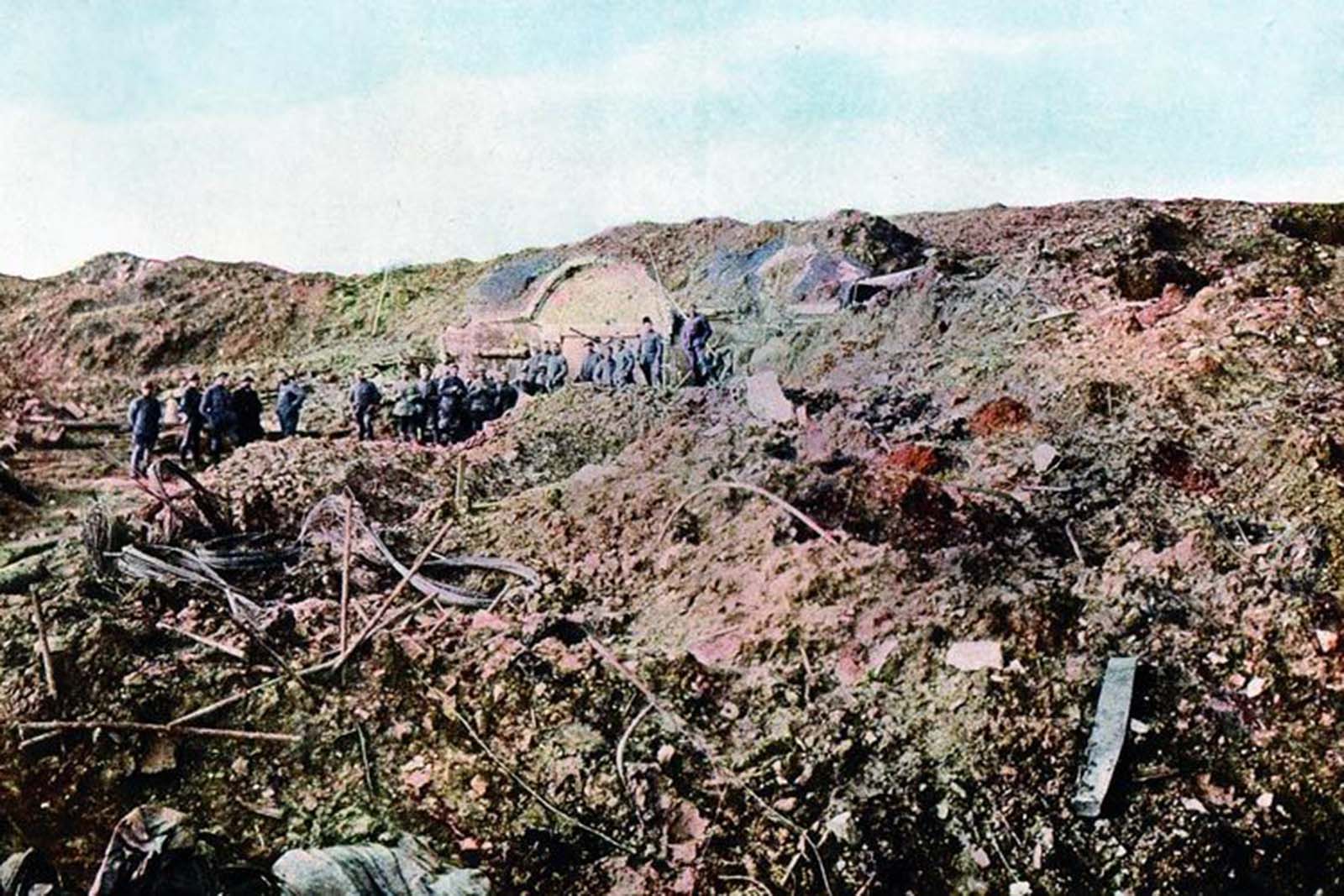

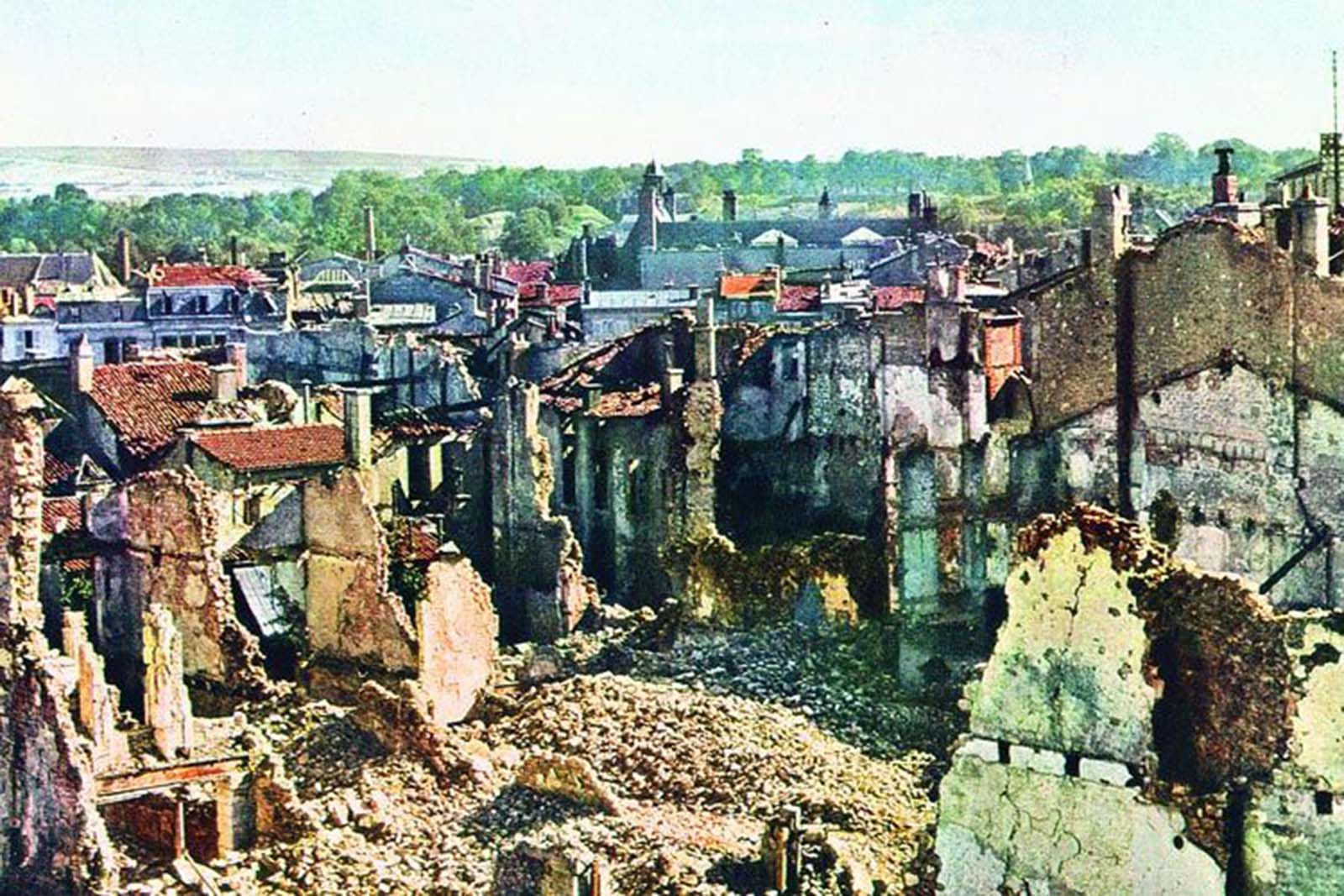

“In 1914, Germany was the world technology leader in photography and had the best grasp of its propaganda value,” writes R.G. Grant in World War I: The Definitive Visual History. “Some 50 photographers were embedded with its forces, compared with 35 for the French. The British military authorities lagged behind. It was not until 1916 that a British photographer was allowed on the Western Front.” But among his countrymen, only Hildebrand took pictures in color. Hildebrand’s images thus stand out with their almost unreal-looking vividness, a result achieved not simply by his use of color film, but by his relatively long experience with a still fairly new medium. He’d already founded a color film society in his native Stuttgart three years before the Archduke’s assassination and had tried his hand at autochrome printing as early as 1909. Hildenbrand’s scenes are all posed, not for reasons of propaganda, but rather because the film he was working with wasn’t sensitive enough to capture movement. Still, they give us a clearer idea of the situation than do most contemporary images. One of the most striking things about Hildenbrand’s oeuvre is how freely he records scenes of destruction. During World War II, both sides became much pickier about what kinds of scenes they would let photographers document. During World War I, images of destroyed churches were a persistent motif. Hardly a glorification, Hildebrand’s work seems to speak to what those of us now, one hundred years in the future, would come to see in World War I: its misery, its oppressive sense of futility, and the haunting destruction it left behind. World War I was a significant turning point in the political, cultural, economic, and social climate of the world. The war and its immediate aftermath sparked numerous revolutions and uprisings. The Big Four (Britain, France, the United States, and Italy) imposed their terms on the defeated powers in a series of treaties agreed at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the most well known being the German peace treaty: the Treaty of Versailles. Ultimately, as a result of the war, the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian Empires ceased to exist, and numerous new states were created from their remains. However, despite the conclusive Allied victory (and the creation of the League of Nations during the Peace Conference, intended to prevent future wars), a second world war followed just over twenty years later. (Photo credit: Hans Hildenbrand / Spiegel / Open Culture). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe