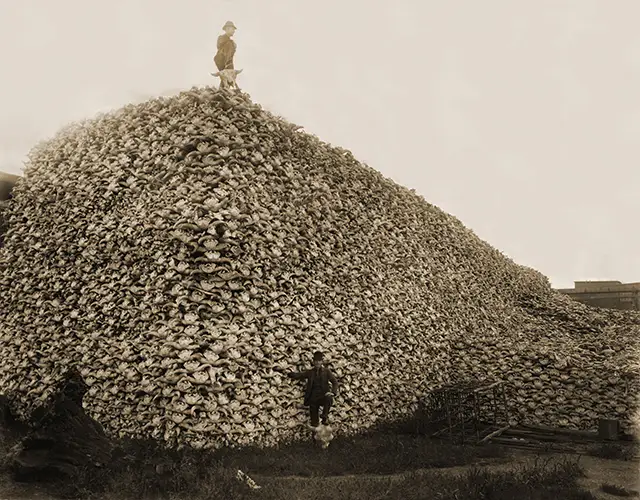

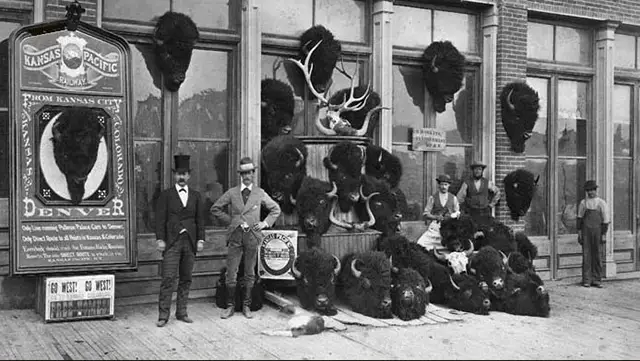

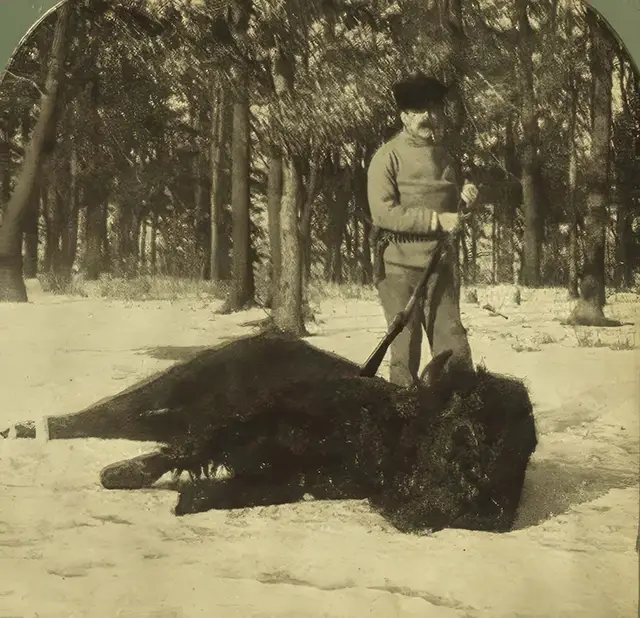

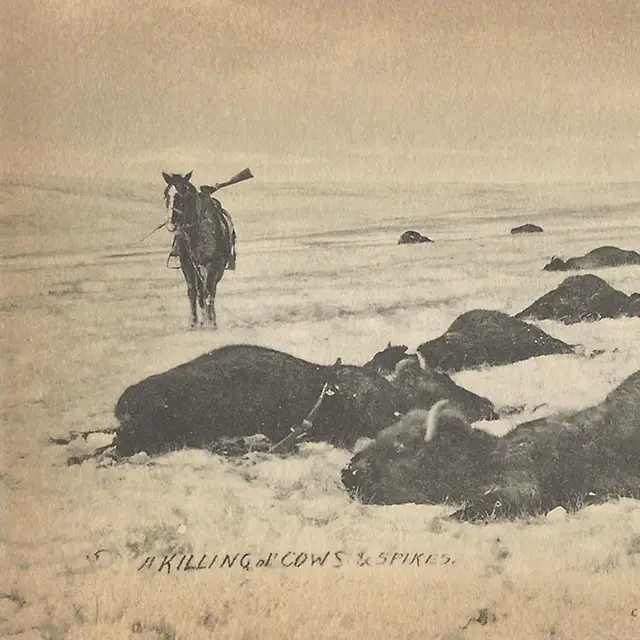

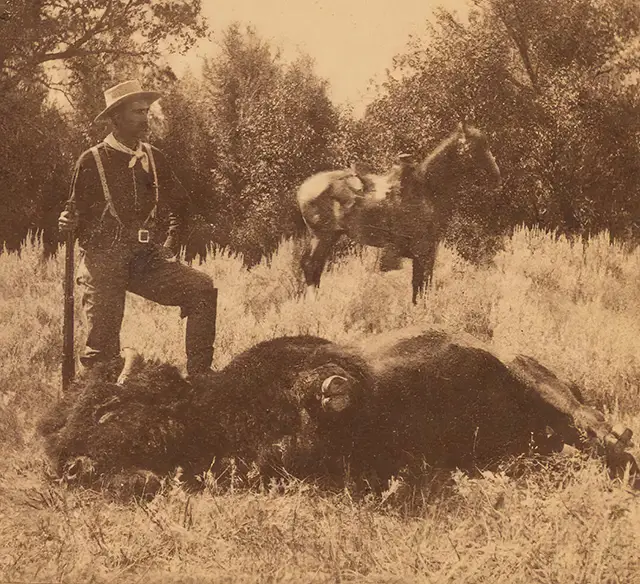

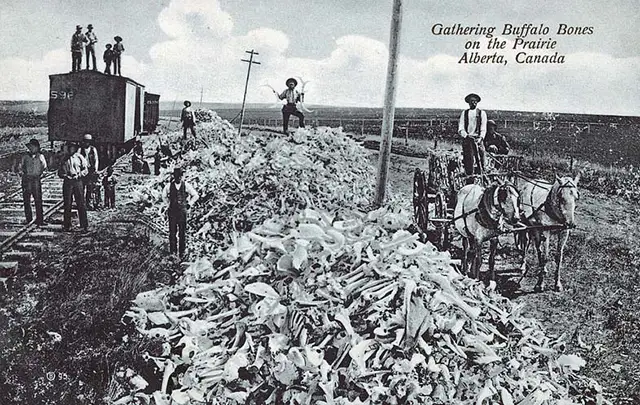

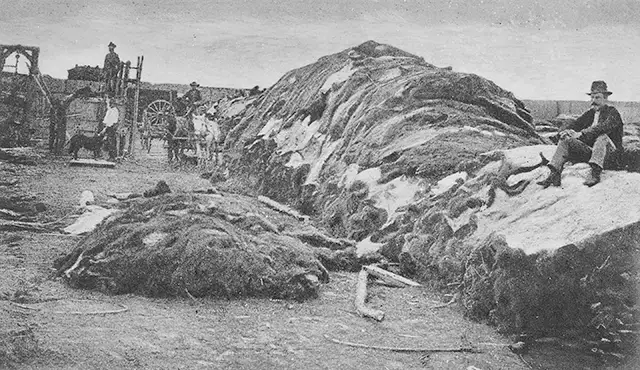

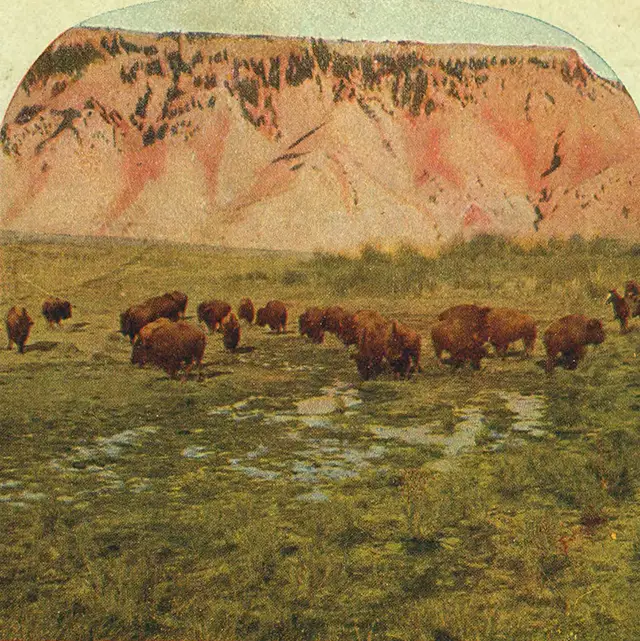

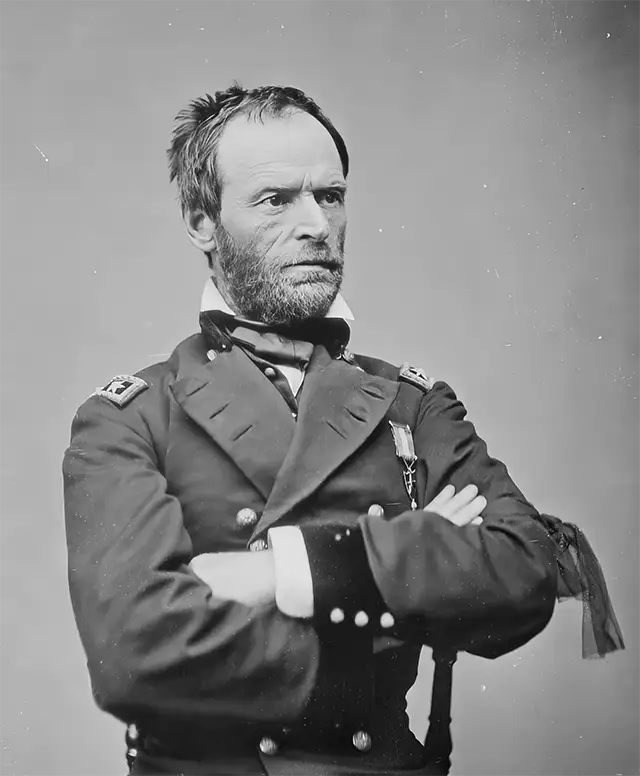

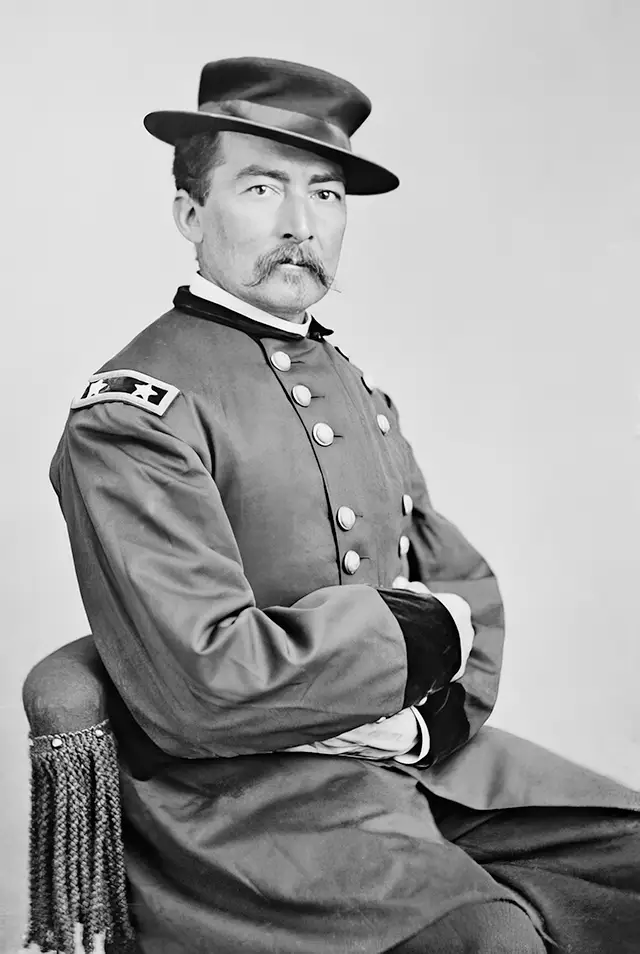

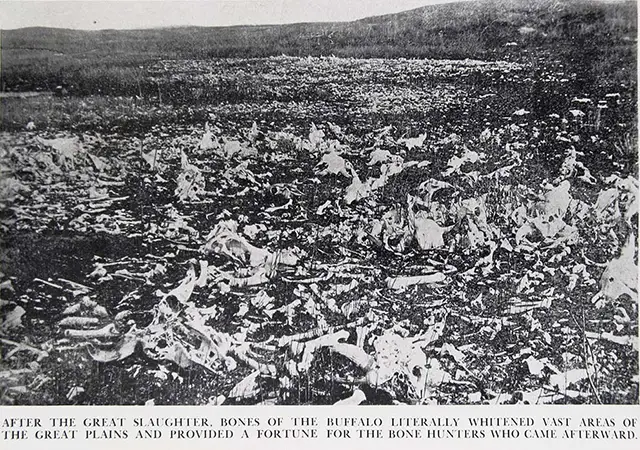

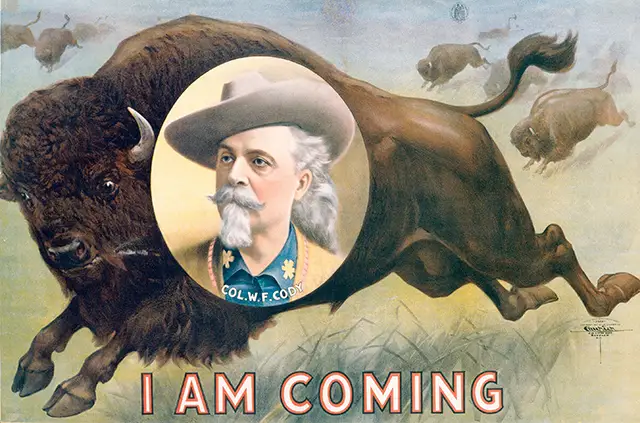

As the United States expanded westward in the early 1800s, a booming trade in American Bison fur, skin, and meat flourished across the Great Plains. By the 1860s, these iconic animals had roamed the plains for millennia, their thunderous herds numbering in the tens of millions, a spectacle so awe-inspiring that it was dubbed the “Thunder of the Plains.” For generations, they had been the lifeblood of Native American tribes, providing not just food and clothing but also shelter and spiritual significance. But the landscape began to shift after the Civil War. The relentless march of the railroad brought with it a wave of new towns, bustling trains, and interconnected telegraph lines, heralding an era of rapid change. This transformation spelled trouble for the bison, as European settlers, spurred by profit, decimated the once-plentiful herds. By the 1880s, their numbers had plummeted from around 30 million to a mere 325, marking a catastrophic decline. Before horses were introduced, Native American hunters used innovative methods to hunt bison. They would guide the animals into large chutes made of rocks and willow branches, then trap them in a corral known as a buffalo pound. Once contained, the bison were either slaughtered on the spot or driven over cliffs in a practice called buffalo jumps. Archaeological sites containing both pounds and jumps can be found in various locations across the U.S. and Canada. The arrival of horses, originally brought by the Spanish, revolutionized hunting techniques. By the early 1700s, horses had become integral to the nomadic hunting cultures of Indigenous groups. This advancement allowed tribes, once confined to the eastern regions, to move westward in pursuit of the larger bison populations found on the Great Plains. The horse was the missing tool that made it possible for Native Americans to begin a systematic exploitation of the enormous resource of protein, fat, and hides that was stored in the bodies of an estimated 30 million bison in the Plains. On horseback, hunters could follow the migrating herds more closely and over a wider range, kill the animals more efficiently, and carry back more meat and hides. Attracted by previously unimagined hunting possibilities, Native Americans poured into the Plains from all directions, creating one of most renowned hunting cultures in history. By the early 19th century, Plains Native Americans had perfected a range of horseback bison-hunting methods tailored to the region’s seasons and landscapes. In winter, they guided bison into snow-filled gulches or drifts, while summer hunts led them to swamps, rivers, or makeshift corrals. In the Northern Plains, where horses were scarce, many tribes relied on traditional methods like the foot surround. To control bison movements, Plains tribes often burned sections of grasslands. Yet, the most popular technique was the mounted chase. Here, hunters galloped after bison on swift horses, using lances or arrows to strike their prey. Despite the availability of muskets, hunters preferred the short bow for its ease of use on horseback and the scarcity of gunpowder and shot, which were typically saved for warfare. It was during this period that most Plains Native Americans developed a singular dependency on the buffalo. The western Plains became the domain of highly specialized hunter-nomads who fed, clothed, sheltered, and decorated themselves from the skin, flesh, fat, and bones of the bison. What they could not get by hunting, they acquired by trading surplus hides, dried meat, pemmican, and other products of the hunt. Such reliance on a narrow ecological base ultimately proved unsustainable, pushing the bison populations into a steep decline by the mid–19th century. The traditional hunting culture of Plains Native Americans met its demise in the 1870s and 1880s, as commercial European-American hunters nearly exterminated the bison. In contrast to Indigenous practices, where hunters harvested only what was necessary and utilized every part of the animal, European settlers engaged in mass hunting for the skins and tongues of bison, leaving the rest of the carcass to waste away. As the animals decomposed, their bones were gathered and transported in large quantities back east. The roaming nature of bison made them easy targets for European hunters. When one bison in a herd is killed, the other bison gather around it. Due to this pattern, the ability of a hunter to kill one bison often led to the destruction of a large herd of them. In 1889, an essay in a journal of the time observed: Thirty years ago millions of the great unwieldy animals existed on this continent. Innumerable droves roamed, comparatively undisturbed and unmolested … Many thousands have been ruthlessly and shamefully slain every season for past twenty years or more by white hunters and tourists merely for their robes, and in sheer wanton sport, and their huge carcasses left to fester and rot, and their bleached skeletons to strew the deserts and lonely plains. For settlers in the Plains region, bison hunting became a key economic activity. Trappers and traders earned their livelihoods by selling buffalo fur; during the winter of 1872–1873 alone, over 1.5 million buffalo were shipped by train to the east. Apart from the profits derived from buffalo leather, which was commonly used for machinery belts and army boots, the rise of buffalo hunting also led Native Americans to rely more on beef from cattle. Commercial bison hunting became increasingly prevalent during this period. Many military forts supported hunters, who often had civilian connections near their base. While officers hunted bison for both sustenance and sport, it was the professional hunters who had a significant impact on the decline of the bison population. Fort Hays and Wallace even saw competitions like the “buffalo shooting championship of the world,” featuring figures such as “Medicine Bill” Comstock and “Buffalo Bill” Cody. The US Army sanctioned and actively endorsed the wholesale slaughter of bison herds. The federal government promoted bison hunting for various reasons, primarily to pressure the native people onto the Indian reservations during times of conflict by removing their main food source. Without the bison, native people of the plains were often forced to leave the land or starve to death. One of the biggest advocates of this strategy was General William Tecumseh Sherman. On June 26, 1869, the Army Navy Journal reported: “General Sherman remarked, in conversation the other day, that the quickest way to compel the Indians to settle down to civilized life was to send ten regiments of soldiers to the plains, with orders to shoot buffaloes until they became too scarce to support the redskins.” Finnish historian Pekka Hämäläinen suggests that certain Native American tribes also played a role in the decline of the bison in the southern Plains. By the 1830s, the Comanche and their allies were hunting around 280,000 bison annually, pushing the region’s sustainability limit. The introduction of firearms and horses, alongside a growing demand for buffalo robes and meat, led to an escalating number of bison being killed each year. A prolonged and intense drought hit the southern plains in 1845, lasting into the 1860s, causing a widespread collapse of the bison herds. However, by the 1860s, the rains returned, and the bison herds began to recover to some extent. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, cartridge reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and recast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters, such as Buffalo Bill Cody, killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their careers. One professional hunter killed over 20,000 by his count. The average prices paid the buffalo hunters from 1880 to 1884 were as follows. For cow hides, $3; bull hides, $2.50; yearlings, $1.50; calves, $0.75 cents; and the cost of getting the hides to market brought the cost up to about $3.50 ($89.68 accounting for inflation) per hide. For a decade after 1873, there were several hundred, perhaps over a thousand, such commercial hide-hunting outfits harvesting bison at any one time, vastly exceeding the take by Native Americans or individual meat hunters. The commercial take arguably was anywhere from 2,000 to 100,000 animals per day depending on the season, though there are no statistics available. Due to the mass slaughter of bison during the 1870s, the plains bison population underwent a population bottleneck. The population plummeted from an estimated 60 million individuals, as observed by Colonel R.I. Dodge along the Arkansas River in Kansas in 1871, to a founding population of around 100 individuals. These survivors were divided into six herds, with five managed by private ranchers and one by the New York Zoological Park (now the Bronx Zoo). Additionally, a wild herd of 25 individuals in Yellowstone National Park survived the bottleneck. From the late 19th century onwards, the bison population gradually rose from 325 in 1884 to 500,000 in 2017, as a result of careful preservation and a general population boom. Although they are no longer classified as endangered, there are still conservation efforts in order to prevent population crashes down the line.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe