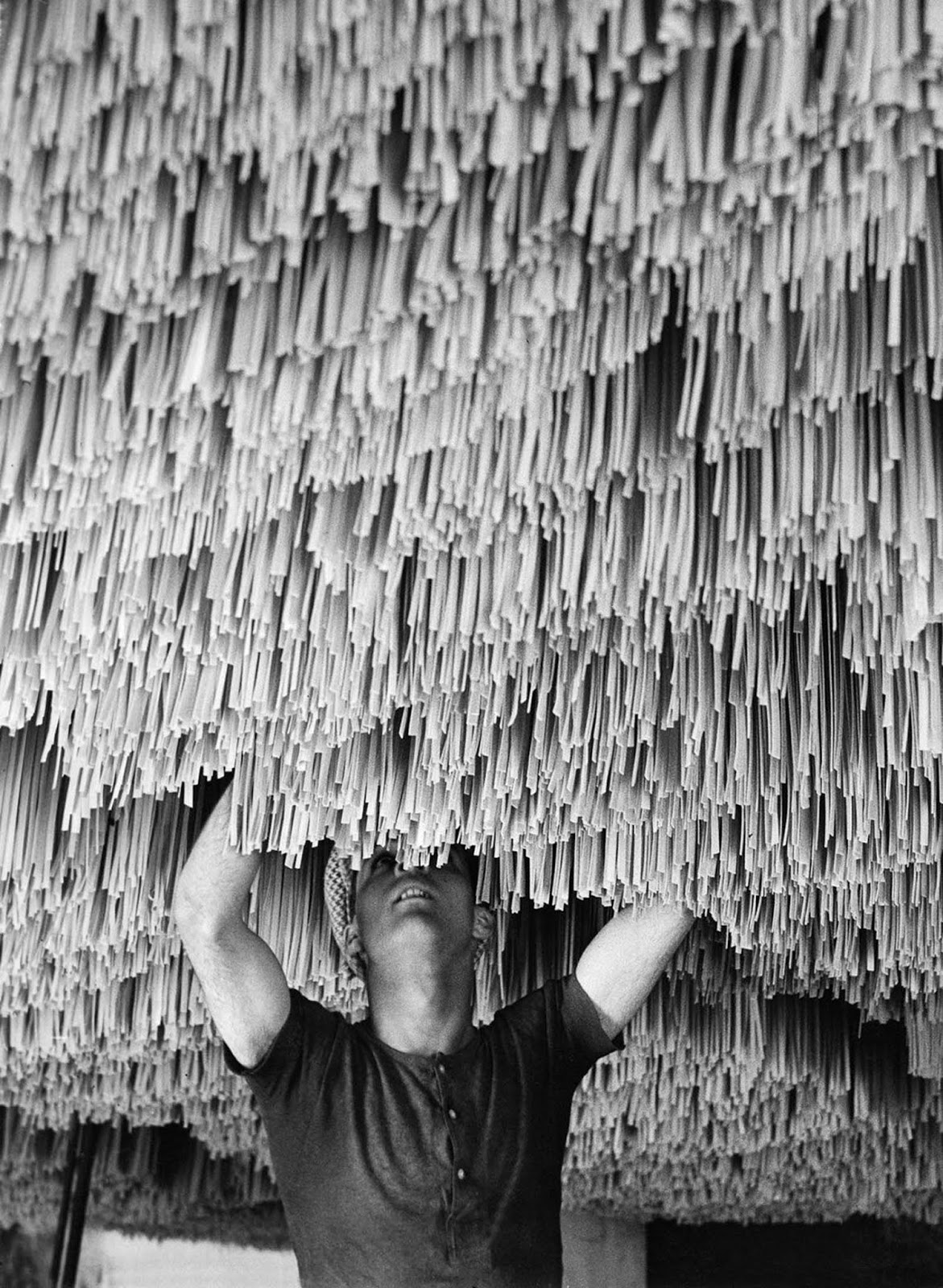

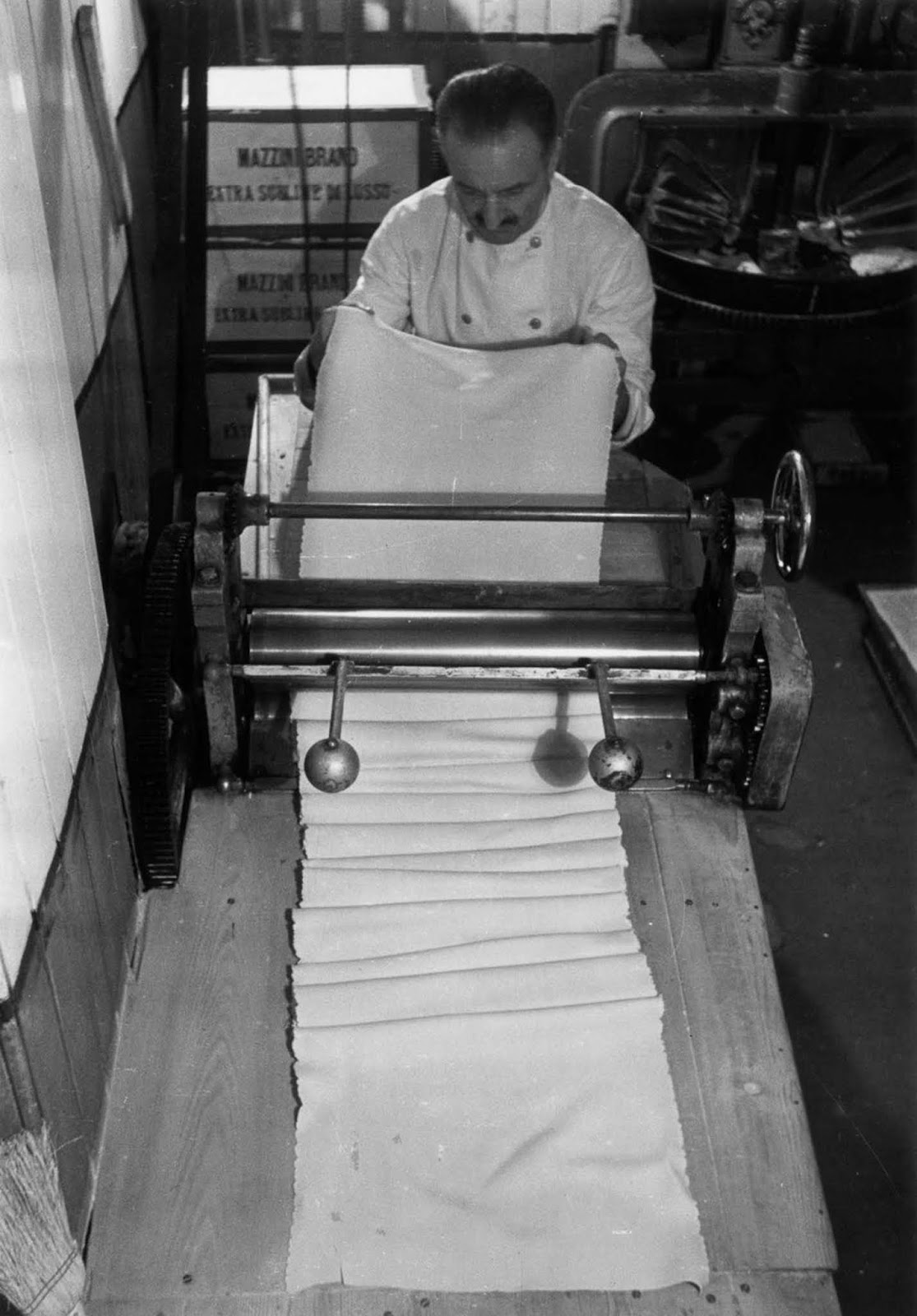

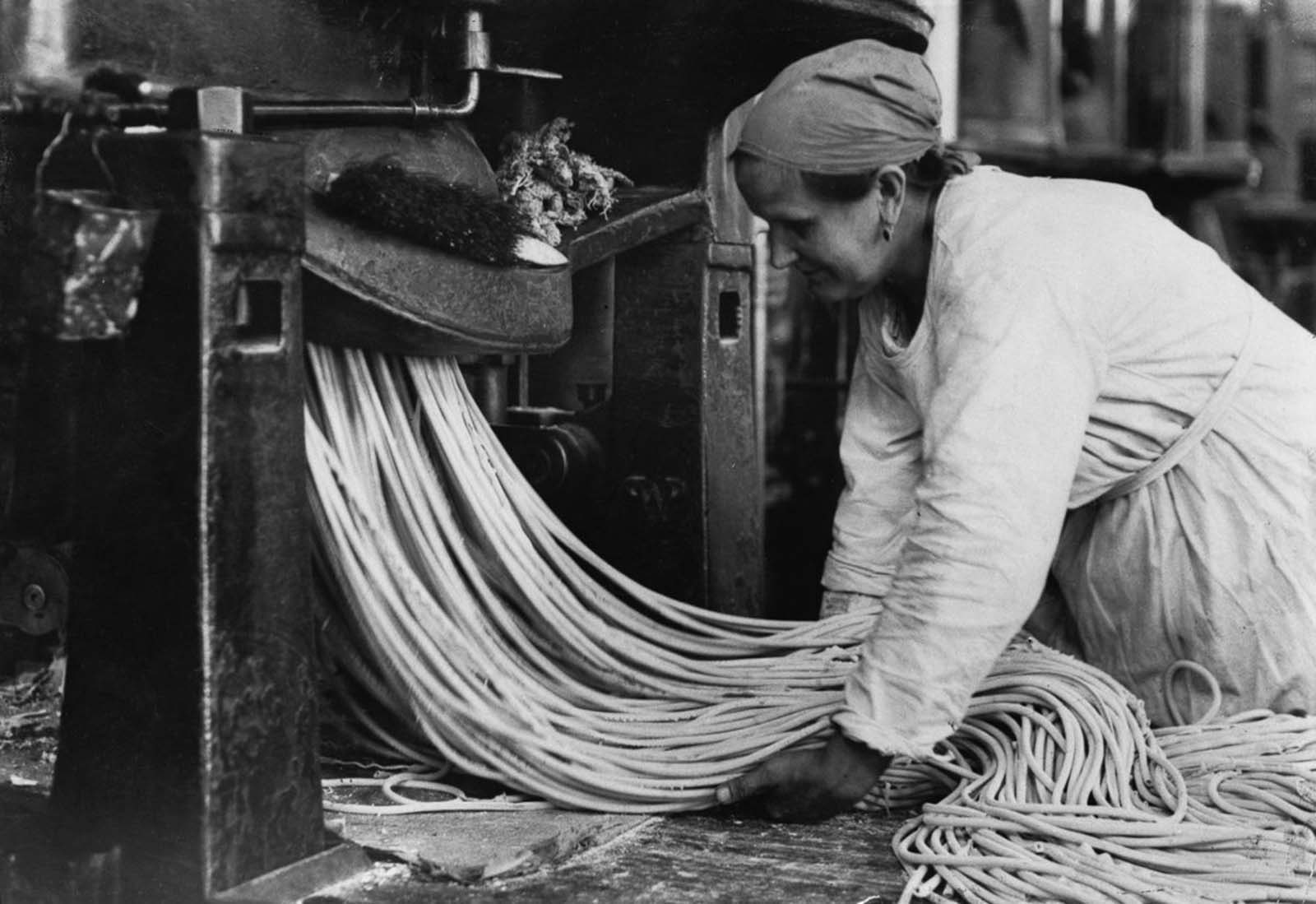

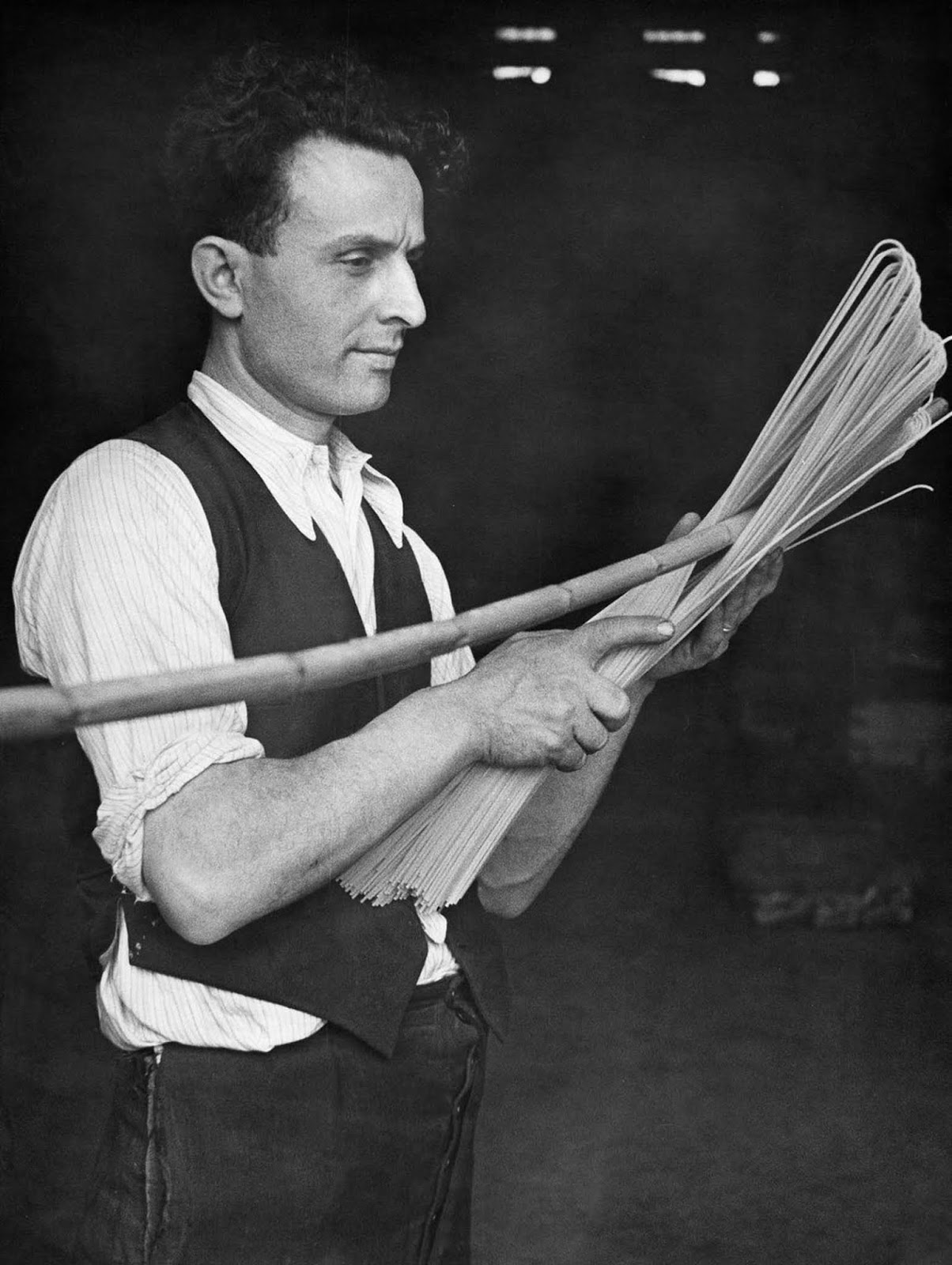

Many school children were taught that the Venetian merchant Marco Polo brought back pasta from his journeys to China. Some may have also learned that Polo’s was not a discovery, but rather a rediscovery of a product once popular in Italy among the Etruscans and the Romans. Well, Marco Polo might have done amazing things on his journeys, but bringing pasta to Italy was not one of them: noodles were already there in Polo’s time. There is indeed evidence of an Etrusco-Roman noodle made from the same durum wheat used to produce modern pasta: it was called “lagane” (origin of the modern word for lasagna). However, this type of food, first mentioned in the 1st century AD, was not boiled, as it is usually done today, but oven-baked. Ancient lagane had some similarities with modern pasta, but cannot be considered quite the same. The modern word “macaroni” derives from the Sicilian term for kneading the dough with energy, as early pasta making was often a laborious, day-long process. How these early dishes were served is not truly known, but many Sicilian pasta recipes still include typically middle eastern ingredients, such as raisins and cinnamon, which may be witness to original, medieval recipes. This early pasta was an ideal staple for Sicily and it easily spread to the mainland since durum wheat thrives in Italy’s climate. By the 1300s dried pasta was very popular for its nutrition and long shelf life, making it ideal for long ship voyages. Pasta made it around the globe during the voyages of discovery a century later. By that time different shapes of pasta have appeared and new technology made pasta easier to make. With these innovations, pasta truly became a part of Italian life. However, the next big advancement in the history of pasta would not come until the 19th century when pasta met tomatoes. Although tomatoes were brought back to Europe shortly after their discovery in the New World, it took a long time for the plant to be considered edible. In fact, tomatoes are a member of the nightshade family, and rumors of tomatoes being poisonous continued in parts of Europe and its colonies until the mid 19th century. Therefore it was not until 1839 that the first pasta recipe with tomatoes was documented. However, shortly thereafter tomatoes took hold, especially in the south of Italy. The rest of course is delicious history. As the production of pasta became increasingly industrialized in the mid-18th century, it was still both expensive and labor-intensive. After harvesting the durum wheat to make flour, the fun truly began. In early factories, workers mixed water and flour to form a paste and then an operator sitting on a wood bar bounced up and down to knead the pasta, a process which took over two hours to complete. Only then could the second team of burly men begin to form the paste into what one would recognize as pasta. With the advent of the torchio, operators known as pastai (extruders) placed the kneaded dough into a cylinder compressed by a screw and, by using a system of levers and ropes, forced out strands of noodles. This is where the real dilemma emerged. After hours of pasta extrusion work, no degree of mechanization could resolve a simple fact – if this pasta was not consumed immediately, it needed to be air-dried in a well-ventilated space. Unfortunately, there was no new invention for drying pasta. Factories had to rely on the same technology as the ancients before them: wind. Thus a new profession was born: the aizacanne, the pasta drier. (Although this type of work likely existed even in Pompeii – people had to dry handmade pasta somehow – it became a true profession as the production of pasta became industrialized.) After pulling long strands of extruded pasta onto spallette (reed bars), the aizacanne walked through the streets constantly maximizing and monitoring their positions to guarantee the preservation of perfectly dried strands of pasta, occasionally using whips to prevent passing animals (and humans) from touching the drying edible gold. Even as late as 1957, many people outside of Italy had no clue how it was made. On April Fool’s Day of that year, the BBC aired a story on Italians enjoying a bumper harvest of spaghetti due to a decline in the “spaghetti weevil.” The program showed Italian and Swiss families cheerfully picking long strands of spaghetti from “spaghetti trees,” and led many viewers to call in, curious about how they could plant their own. These photos from 20th-century pasta factories show the actual process by which the dough is squeezed, shaped, cut, and dried on its way to the dinner table. (Photo credit: Bettmann / Getty Images / Hulton-Deutsch / Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe