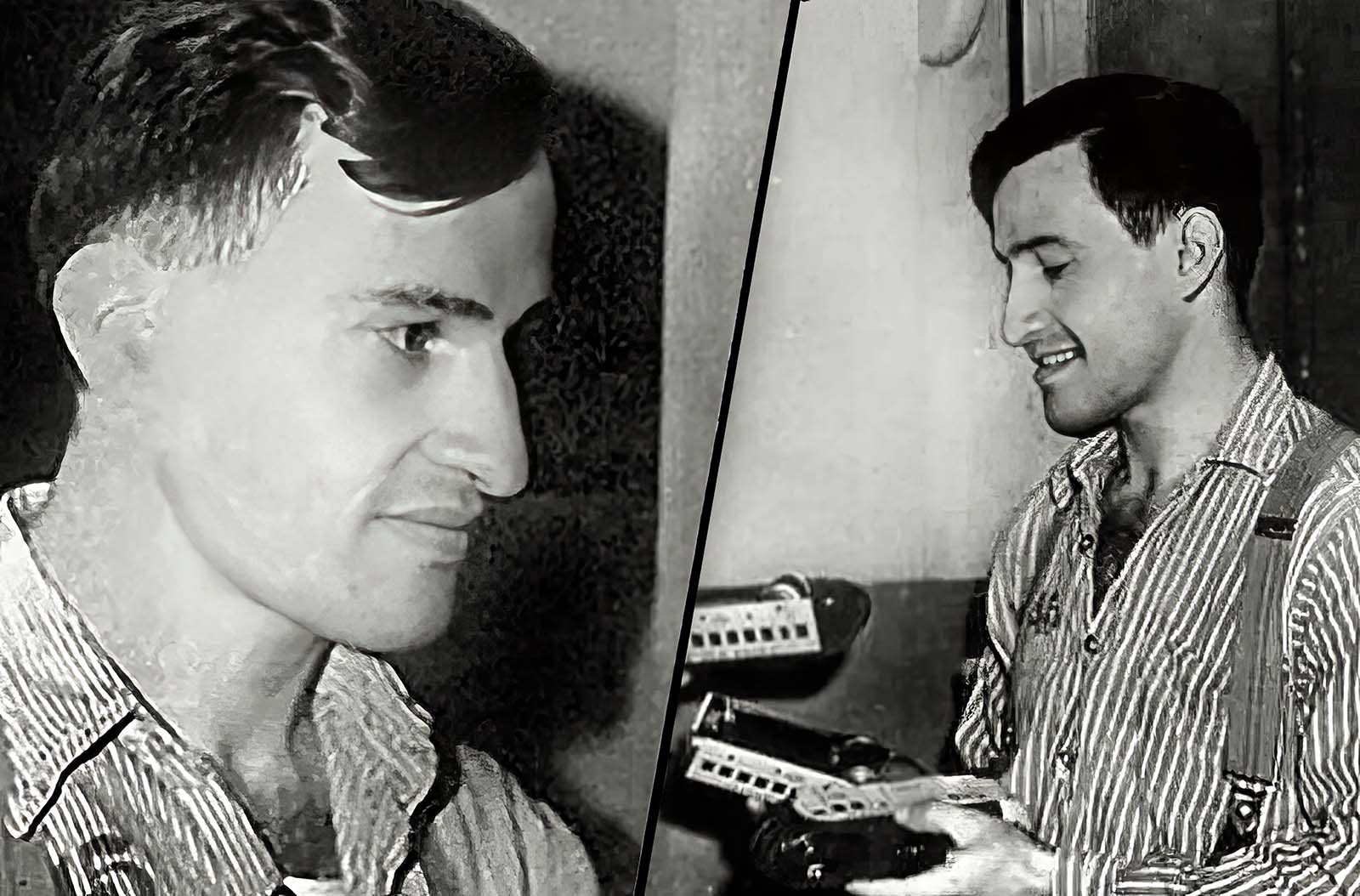

He was just 23, with an IQ of 46. He understood the simple joys of eating, playing, and the world of trains – things you could see, smell, and live. But things like God, justice, and evil were like elusive dreams to him. The doctors called him an “imbecile,” a term for someone who thinks like a child between four and six. When the police pressured him into confessing to a gruesome murder he didn’t commit, his short life met a tragic end. This is the heartbreaking story of Joe Arridy, one of those instances when justice went awry. Joe Arridy was born in 1915 in Pueblo, Colorado, the oldest child of Mary and Henry Arridy, who had recently moved from Syria. They were first cousins and didn’t speak English. For the first five years of his life, Joe didn’t talk. After going to elementary school for just one year, his principal told his parents to keep him at home, saying he could not learn or understand. When Joe was ten, he went to the State Home and Training School for Mental Defectives in Grand Junction, Colorado, where he lived on and off for eleven years until becoming a young adult. Examiners at the home also had Arridy’s family undergo several psychological tests and concluded that his mother Mary was “probably feeble-minded”. Both in his neighborhood and at the school, he was often mistreated and beaten by his peers. In 1929, while living back in Pueblo, Arridy was sexually assaulted by a group of teen boys, aggravating his mental issues. Eventually, he left the school and hopped on freight railcars to leave the city, ending up at the age of 21 in the railyards of Cheyenne, Wyoming, by late August 1936.

The Crime

On the night of August 15, 1936, Dorothy Drain’s parents returned to their Pueblo, Colorado home to discover their 15-year-old daughter lifeless in a pool of her own blood. A fatal blow to the head had taken her life while she slept. Tragically, her younger sister, Barbara, also suffered a head injury but miraculously survived. The vicious attack sent shockwaves through the town, prompting newspapers to sensationalize the situation, declaring the presence of a sex-motivated murderer on the loose. Police were under tremendous pressure to catch the killer and Sheriff George Carroll must have felt nothing but relief when 21-year-old Joe Arridy, who had been found aimlessly wandering near the local railyards, confessed to the murders.

The Arrest of Joe Arridy

On August 26, 1936, Arridy was arrested for vagrancy in Cheyenne, Wyoming, after being apprehended while wandering around the railyards. Although the crime occurred in Colorado, the local sheriff, George Carroll, was aware of the widespread search for suspects in the Drain murder case. When Arridy disclosed during questioning that he had traveled through Pueblo by train after departing from Grand Junction, Colorado, Carroll began to interrogate him about the Drain case. Carroll claimed that Arridy confessed to him. Witness accounts indicated that the individual in close proximity to the crime scene bore a Mexican appearance. It is noteworthy that Joe Arridy’s parents were Syrian immigrants, a detail contributing to his dark complexion. When Carroll contacted the Pueblo police chief Arthur Grady about Arridy, he learned that they had already arrested a man considered to be the prime suspect: Frank Aguilar, a laborer with the Works Progress Administration from Mexico. Aguilar had worked for the father of the Drain girls and been fired shortly before the attack. An axe head was recovered from Aguilar’s home. Sheriff Carroll claimed that Arridy told him several times he had “been with a man named Frank” at the crime scene. Aguilar later confessed to the crime and told police he had never seen or met Arridy. Aguilar was also convicted of the rape and murder of Dorothy Drain and sentenced to death. He was executed on August 13, 1937, in Colorado State Penitentiary. After being transported to Pueblo, Arridy reportedly confessed again. Arridy spoke slowly, struggled with tasks like identifying colors, and had difficulty repeating sentences longer than a couple of words. The superintendent of the state home where Arridy lived remembered him being easily manipulated by other boys. They once convinced him to confess to stealing cigarettes, even though it was impossible for him to do so. Sheriff Carroll seemed to grasp Arridy’s susceptibility to influence, similar to how other boys had taken advantage of him before. Carroll’s questioning approach involved leading questions, like asking about Arridy’s interest in girls and immediately suggesting wrongdoing: “If you like girls so much, why do you hurt them?” The coercive nature of these questions led to swift changes in Arridy’s testimony, depending on the interrogator. Moreover, Arridy remained unaware of key details of the murders, such as the weapon being an ax, until they were presented to him during questioning.

Conviction

During the trial, Arridy’s lawyer argued that his client was not mentally fit, hoping to spare his life. Despite being deemed sane, three state psychiatrists acknowledged Arridy’s severe mental limitations, classifying him as an “imbecile” based on the medical terminology of that time. They pointed out his IQ of 46, equivalent to that of a six-year-old, and emphasized his incapacity to distinguish between right and wrong, making him unable to engage in actions with criminal intent. Arridy was convicted largely due to his false confession, a vulnerability often observed in individuals with limited mental capacity during interrogations. Notably, there was no physical evidence against him. Barbara Drain’s testimony implicated Aguilar in the attack, not Arridy, as she could identify Aguilar due to his prior work for her father. Despite the weakness of the evidence, Arridy was found guilty and sentenced to death. Attorney Gail L. Ireland, who later was elected and served as Colorado Attorney General and Colorado Water Commissioner, became involved as defense counsel in Arridy’s case after his conviction and sentencing. While Ireland won several delays of Arridy’s execution, he was unable to get his conviction overturned or commutation of his sentence.

The execution of Joe Arridy

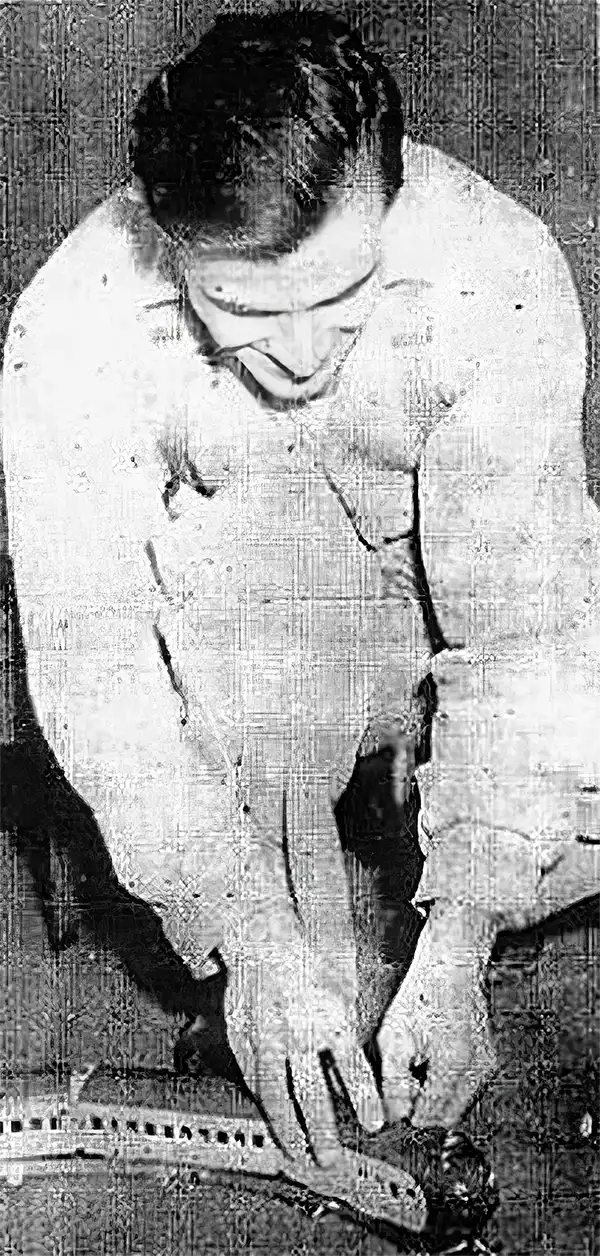

While awaiting appeals on death row, Arridy found solace in playing with a toy train, a thoughtful gift from prison warden Roy Best. According to Best, Arridy was considered “the happiest prisoner on death row.” Both fellow inmates and guards treated him well. Warden Best became a strong supporter of Arridy, actively contributing to efforts to spare his life. Their bond was profound, with Best caring for Arridy like a son, regularly bringing him gifts. In reflecting on Arridy’s demeanor before the execution, Best remarked, “He probably didn’t even know he was about to die; all he did was happily sit and play with a toy train I had given him.” For his last meal, Arridy requested ice cream. When confronted about his impending execution, he displayed a “blank bewilderment.”

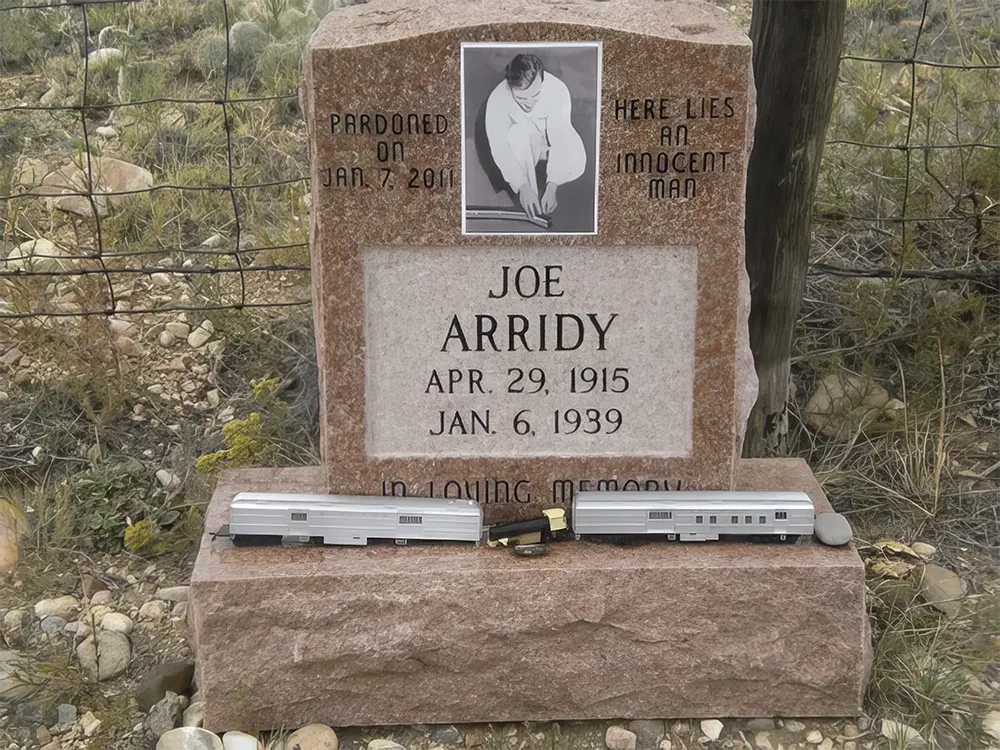

Before being taken to the gas chamber, Arridy hadn’t quite finished his ice cream. He wanted the rest refrigerated, thinking he could enjoy it later—unaware that he wouldn’t be coming back. As he was led to the gas chamber, reports say he smiled. Though a bit nervous initially, he found solace when the warden grabbed his hand and reassured him. The execution happened fairly quickly, but it’s said that Warden Best shed some tears in the chamber. In 2011, Arridy received a full and unconditional posthumous pardon by Colorado Governor Bill Ritter (72 years after his death). Ritter, the former district attorney of Denver, pardoned Arridy based on questions about the man’s guilt and what appeared to be a coerced false confession. This was the first time in Colorado that the governor had pardoned a convict after execution. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress / Colorado Archives). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe