Nestled in the British Hong Kong territory, this unique enclave, covering a mere 6.4 acres (2.6 hectares), was home to tens of thousands of residents and workers for decades. By the 1980s, Kowloon Walled City housed up to 35,000 people, creating an extraordinarily compact community within its confines. The enclave comprised 350 buildings interconnected by hundreds of narrow alleyways. Known as the “City of Darkness,” it earned this name due to its severe lack of natural light. The story of Kowloon Walled City poses interesting questions. How did this unique city come to be, and why was it eventually destroyed? This is the fascinating story of a ‘city’ once recognized as the most densely populated place on Earth.

The Early History of Kowloon Walled City

The history of the walled city can be traced back to the Song dynasty (960–1279), when a military outpost was set up to manage the salt trade in the area. Little took place for hundreds of years afterward, although 30 guards were stationed there in 1668. In 1842, during Qing Daoguang Emperor’s reign, Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Nanking. As a result, the Qing authorities felt it necessary to improve the fort to rule the area and check further British influence. The improvements, including the formidable defensive wall, were completed in 1847. The Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory of 1898 handed additional parts of Hong Kong (the New Territories) to Britain for 99 years, but excluded the walled city, which at the time had a population of roughly 700. China was allowed to continue to keep officials there as long as they did not interfere with the defense of British Hong Kong. Over the years, China firmly held onto this small piece of land. After World War II, even though much of it was damaged, people flocked to the area seeking refuge. They knew they could rely on support from the Chinese government if Hong Kong officials tried to make them leave. The Chinese defended the thousands of refugees, making any attempts to force them out unsuccessful. As time passed, the refugee camp started turning into something more permanent and lasting.

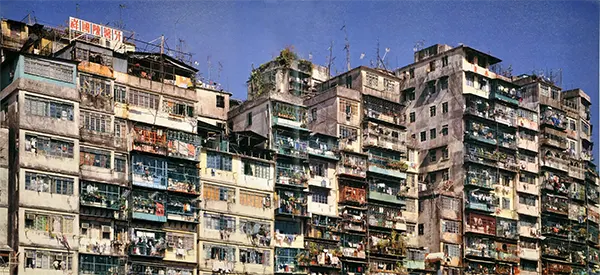

Layout and Architecture

Despite its evolution from a fort to an urban enclave, the walled city maintained its original layout. The initial fort occupied a sloped area, covering a 2.6-hectare (6.4-acre) plot measuring approximately 210 by 120 meters (690 by 390 feet). In the 1960s and 1970s, construction activities soared, transforming the once low-rise city into a landscape dominated by buildings with 10 stories or more, except for the central yamen. However, due to the proximity of Kai Tak Airport, located 800 meters (0.50 miles) south of the city, buildings were restricted to a maximum height of 14 stories. The city’s numerous alleyways, often measuring just 1–2 meters (3.3–6.6 feet) in width, lacked proper lighting and drainage. An intricate network of staircases and passageways emerged on upper levels, allowing one to traverse the entire city from north to south without ever touching solid ground. Construction within the city operated without regulation, resulting in around 350 buildings with poor foundations and minimal utilities. Because apartments were so small—a typical unit was 23 m2 (250 sq ft)—space was maximized with wider upper floors, caged balconies, and rooftop additions. Roofs in the city were full of television antennas, clotheslines, water tanks, and rubbish, and could be crossed using a series of ladders. Official census numbers estimated the walled city’s population at 10,004 in 1971 and 14,617 in 1981, but these figures were commonly considered to be much too low. A thorough government survey in 1987 gave a clearer picture: an estimated 33,000 people resided within the walled city. Based on this survey, the walled city had a population density of approximately 1,255,000 inhabitants per square kilometer (3,250,000/sq mi) in 1987, making it the most densely populated spot in the world.

Life Inside Kowloon Walled City

Facing tough living conditions, the residents formed a close-knit community, providing mutual support in the face of challenges. Within families, wives typically handled housekeeping, while grandmothers looked after both their grandchildren and kids from nearby homes. The city’s rooftops served as important gathering spots, especially for those living on upper floors. Parents used them for relaxation, and after school, children often played or did homework there. In the 1950s, triad groups, including the 14K and Sun Yee On, established control over the walled city’s many brothels, gaming parlors, and opium dens. The criminal presence became so pervasive that police would only enter the area in large groups. It wasn’t until 1973 and 1974, marked by more than 3,500 police raids resulting in over 2,500 arrests, that the triads’ influence began to decline. Public support, especially from younger residents, contributed to the success of these raids, gradually reducing drug use and violent crime. By 1983, the district police commander declared the walled city’s crime rate to be under control. While the walled city’s crime diminished in later years, it remained known for its abundance of unlicensed doctors and dentists operating without fear of prosecution. Despite its history as a hub for criminal activity, the majority of residents lived peacefully within its walls. Numerous small factories and businesses thrived, and some residents formed groups to organize and enhance daily life.

Why and How Kowloon Walled City Was Destroyed

Hong Kong officials had wanted to turn the settlement into a public park for a long time, and in the 1990s, they got their chance. When Britain’s 99-year lease on Hong Kong ended, and the territory went back to China, Kowloon Walled City lost its political importance. The decision to demolish the city was made in 1984 through the Sino-British Joint Declaration. The two governments officially announced the plan to tear down the walled city on January 14, 1987. To make way for the demolition, a special committee of the Hong Kong Housing Authority came up with a plan to compensate the estimated 33,000 residents and businesses, totaling around HK$2.7 billion (US$350 million). However, not everyone was happy with the compensation, and some were forced to leave between November 1991 and July 1992. After four months of planning, the demolition began on March 23, 1993, and finished in April 1994. During the process, developers uncovered various layers of the city’s history, revealing its original wall, iron cannons, and granite plaques marked with the words “South Gate” and “Kowloon Walled City.” The area where the walled city once stood is now Kowloon Walled City Park, adjacent to Carpenter Road Park. The 31,000 m2 (7.7 acres) park was completed in August 1995 and handed over to the local government. The park’s design is modeled on Jiangnan gardens of the early Qing dynasty. It is divided into eight landscape features, with the fully restored yamen as its centerpiece. The park’s paths and pavilions are named after streets and buildings in the walled city. Artifacts from the walled city, such as five inscribed stones and three old wells, are also on display in the park.

Many authors, filmmakers, game designers, and visual artists have used the walled city to convey a sense of oppressive urbanization or unfettered criminality. In literature, Robert Ludlum’s novel The Bourne Supremacy uses the walled city as one of its settings. The 1982 Shaw Brothers film Brothers from the Walled City is set in Kowloon Walled City. The 1984 gangster film Long Arm of the Law features the walled city as a refuge for gang members before they are gunned down by police. In the 1988 film Bloodsport, starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, the walled city is the setting for a martial arts tournament. The 1992 non-narrative film Baraka features several highly detailed shots of the walled city shortly before its demolition. The 1993 film Crime Story starring Jackie Chan was partly filmed in the deserted walled city, and includes real scenes of building explosions (Photo credit: South China Morning Post / Wikimedia Commons / Flickr). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe