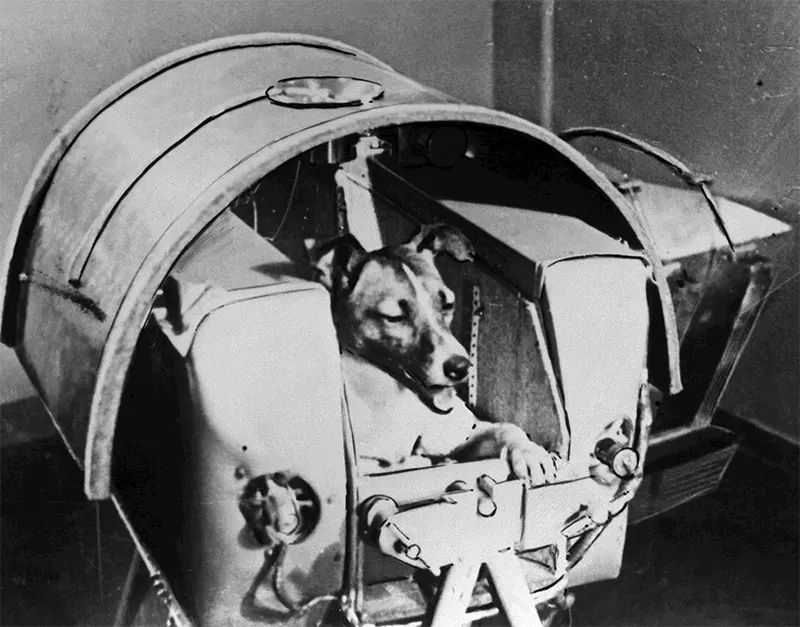

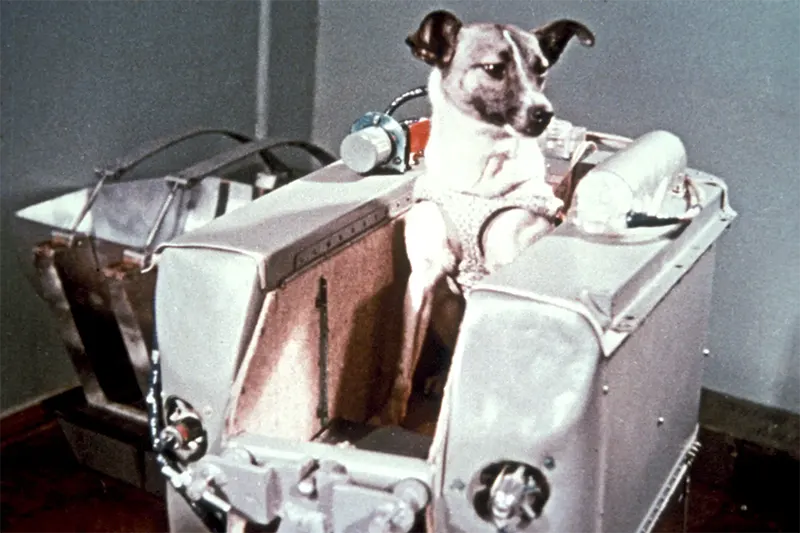

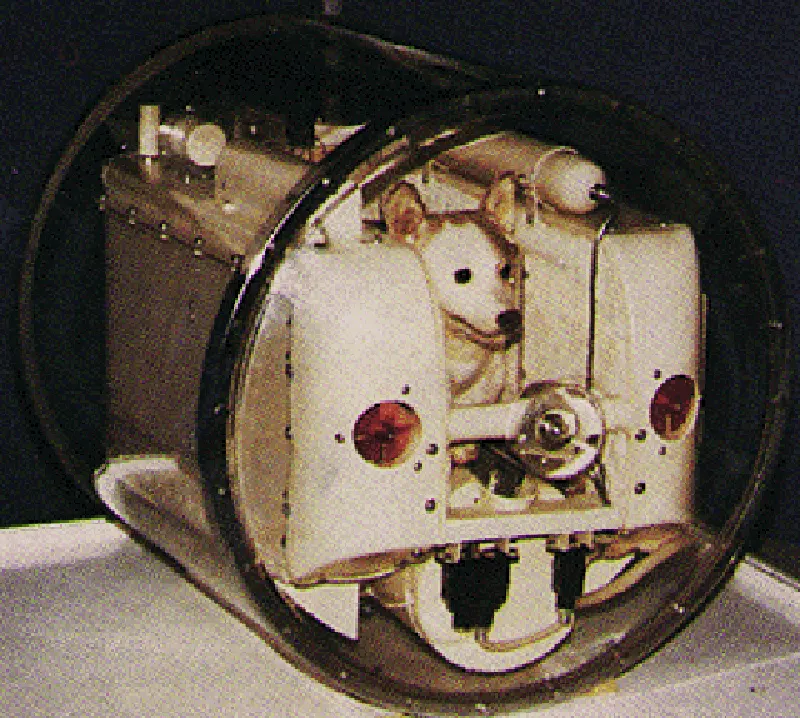

This achievement was hailed as a triumph of Soviet engineering and innovation, but it came at a tragic cost. Laika’s mission was a one-way trip, and she perished in space just hours after launch. The experiment, which monitored Laika’s vital signs, aimed to prove that a living organism could survive being launched into orbit and continue to function under conditions of weakened gravity and increased radiation, providing scientists with some of the first data on the biological effects of spaceflight. Despite her short life, Laika became a symbol of bravery and sacrifice, capturing the imagination of people around the world and inspiring future generations of space explorers. Laika was found as a stray wandering the streets of Moscow a week before the launch. Soviet scientists chose to use Moscow strays since they assumed that such animals had already learned to endure conditions of extreme cold and hunger. She was a 5 kg (11 lb) mongrel female, approximately three years old. Soviet personnel gave her several names and nicknames, among them Kudryavka (Russian for Little Curly), Zhuchka (Little Bug), and Limonchik (Little Lemon). Laika, the Russian name for several breeds of dogs similar to the husky, was the name popularized around the world. Its literal translation would be “Barker”. The American press dubbed her Muttnik (mutt + suffix -nik) as a pun on Sputnik, or referred to her as Curly. Her true pedigree is unknown, although it is generally accepted that she was part husky or other Nordic breed, and possibly part terrier. The Soviet Union and United States had previously sent animals only on suborbital flights. Three dogs were trained for the Sputnik 2 flight: Albina, Mushka, and Laika. Soviet space-life scientists Vladimir Yazdovsky and Oleg Gazenko trained the dogs. To adapt the dogs to the confines of the tiny cabin of Sputnik 2, they were kept in progressively smaller cages for periods of up to twenty days. The extensive close confinement caused them to stop urinating or defecating, made them restless, and caused their general condition to deteriorate. Laxatives did not improve their condition, and the researchers found that only long periods of training proved effective. The dogs were placed in centrifuges that simulated the acceleration of a rocket launch and were placed in machines that simulated the noises of the spacecraft. Before the launch one of the mission scientists took Laika home to play with his children. In a book chronicling the story of Soviet space medicine, Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky wrote, “Laika was quiet and charming … I wanted to do something nice for her: She had so little time left to live.” Yazdovsky made the final selection of dogs and their designated roles. Laika was to be the “flight dog” – a sacrifice to science on a one-way mission to space. Albina, who had already flown twice on a high-altitude test rocket, was to act as Laika’s backup. The third dog, Mushka, was a “control dog” – she was to stay on the ground and be used to test instrumentation and life support. Before leaving for the Baikonur Cosmodrome, Yazdovsky and Gazenko conducted surgery on the dogs, routing the cables from the transmitters to the sensors that would measure breathing, pulse, and blood pressure. According to a NASA document, Laika was placed in the capsule of the satellite on 31 October 1957 – three days before the start of the mission. At that time of year, the temperatures at the launch site were extremely low, and a hose connected to a heater was used to keep her container warm. Two assistants were assigned to keep a constant watch on Laika before launch. Just prior to liftoff on 3 November 1957, from Baikonur Cosmodrome, Laika’s fur was sponged in a weak ethanol solution and carefully groomed, while iodine was painted onto the areas where sensors would be placed to monitor her bodily functions. One of the technicians preparing the capsule before final liftoff: “After placing Laika in the container and before closing the hatch, we kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight.” Accounts of the time of launch vary from source to source, given as 05:30:42 or 07:22 Moscow Time. At peak acceleration, Laika’s respiration increased to between three and four times the pre-launch rate. The sensors showed her heart rate was 103 beats/min before launch and increased to 240 beats/min during the early acceleration. After reaching orbit, Sputnik 2’s nose cone was jettisoned successfully; however, the “Block A” core did not separate as planned, preventing the thermal control system from operating correctly. Some of the thermal insulation tore loose, raising the cabin temperature to 40 °C (104 °F). After three hours of weightlessness, Laika’s pulse rate had settled back to 102 beats/min, three times longer than it had taken during earlier ground tests, an indication of the stress she was under. The early telemetry indicated that Laika was agitated but eating her food. After approximately five to seven hours into the flight, no further signs of life were received from the spacecraft. The Soviet scientists had planned to euthanize Laika with a serving of poisoned food. For many years, the Soviet Union gave conflicting statements that she had died either from asphyxia, when the batteries failed, or that she had been euthanized. Many rumors circulated about the exact manner of her death. In 1999, several Russian sources reported that Laika had died when the cabin overheated on the fourth orbit. In October 2002, Dimitri Malashenkov, one of the scientists behind the Sputnik 2 mission, revealed that Laika had died by the fourth circuit of flight from overheating. According to a paper he presented to the World Space Congress in Houston, Texas, “It turned out that it was practically impossible to create a reliable temperature control system in such limited time constraints.” Over five months later, after 2,570 orbits, Sputnik 2 (including Laika’s remains) disintegrated during reentry on 14 April 1958. Sputnik 2 was not designed to be retrievable, and it had always been accepted that Laika would die. The mission sparked a debate across the globe on the mistreatment of animals and animal testing in general to advance science. In the United Kingdom, the National Canine Defence League called on all dog owners to observe a minute’s silence on each day Laika remained in space. Animal rights groups at the time called on members of the public to protest at Soviet embassies. Others demonstrated outside the United Nations in New York. In the Soviet Union, there was less controversy. Neither the media, books in the following years, nor the public openly questioned the decision to send a dog into space. In 1998, after the collapse of the Soviet regime, Oleg Gazenko, one of the scientists responsible for sending Laika into space, expressed regret for allowing her to die: Work with animals is a source of suffering to all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We shouldn’t have done it … We did not learn enough from this mission to justify the death of the dog. Laika is memorialized in the form of a statue and plaque at Star City, the Russian Cosmonaut training facility. Created in 1997, Laika is positioned behind the cosmonauts with her ears erect. The Monument to the Conquerors of Space in Moscow, constructed in 1964, also includes Laika. On 11 April 2008 at the military research facility where staff had been responsible for readying Laika for the flight, officials unveiled a monument of her poised on top of a space rocket. Stamps and envelopes picturing Laika were produced, as well as branded cigarettes and matches. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Britannica / Russian Archives / NASA / Smithsonian Museum). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe