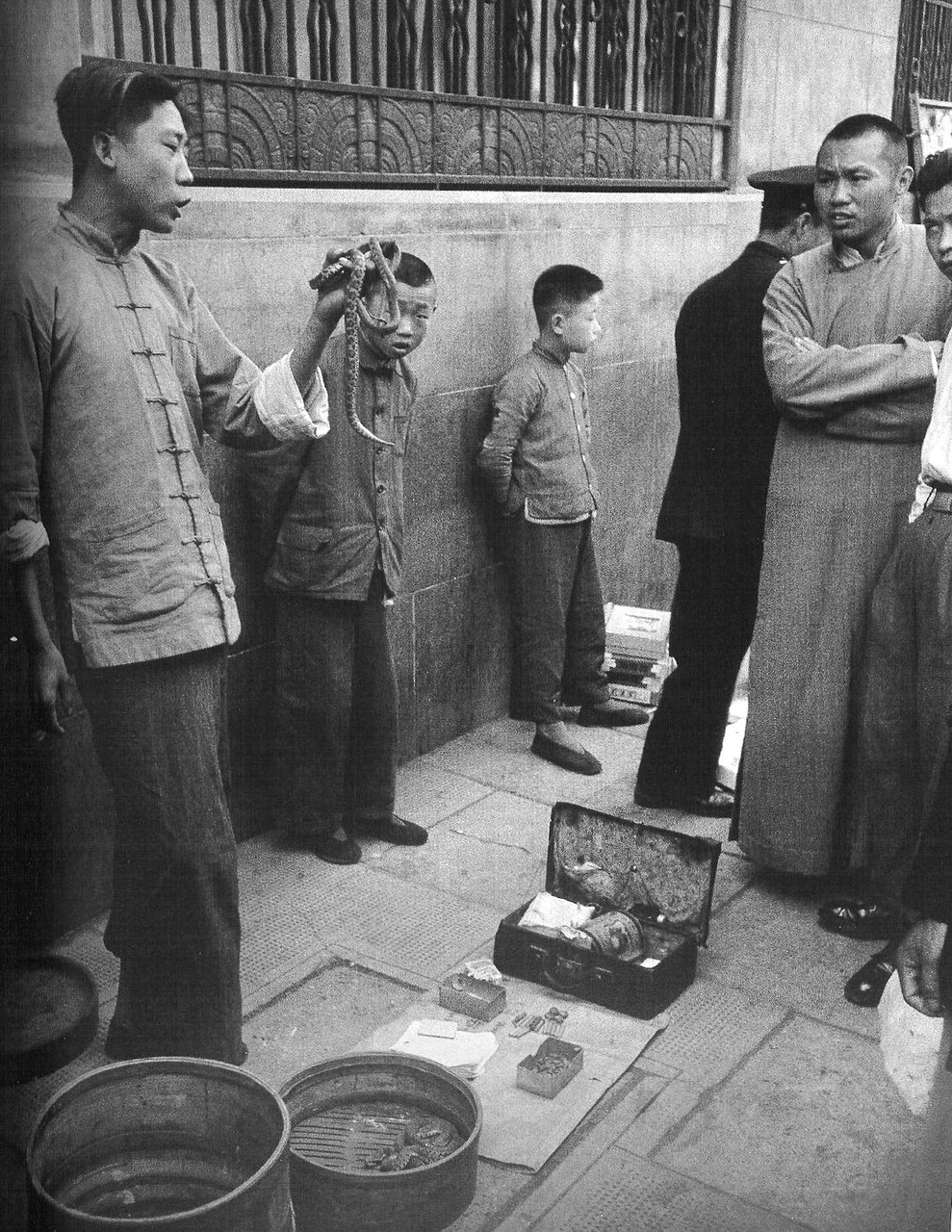

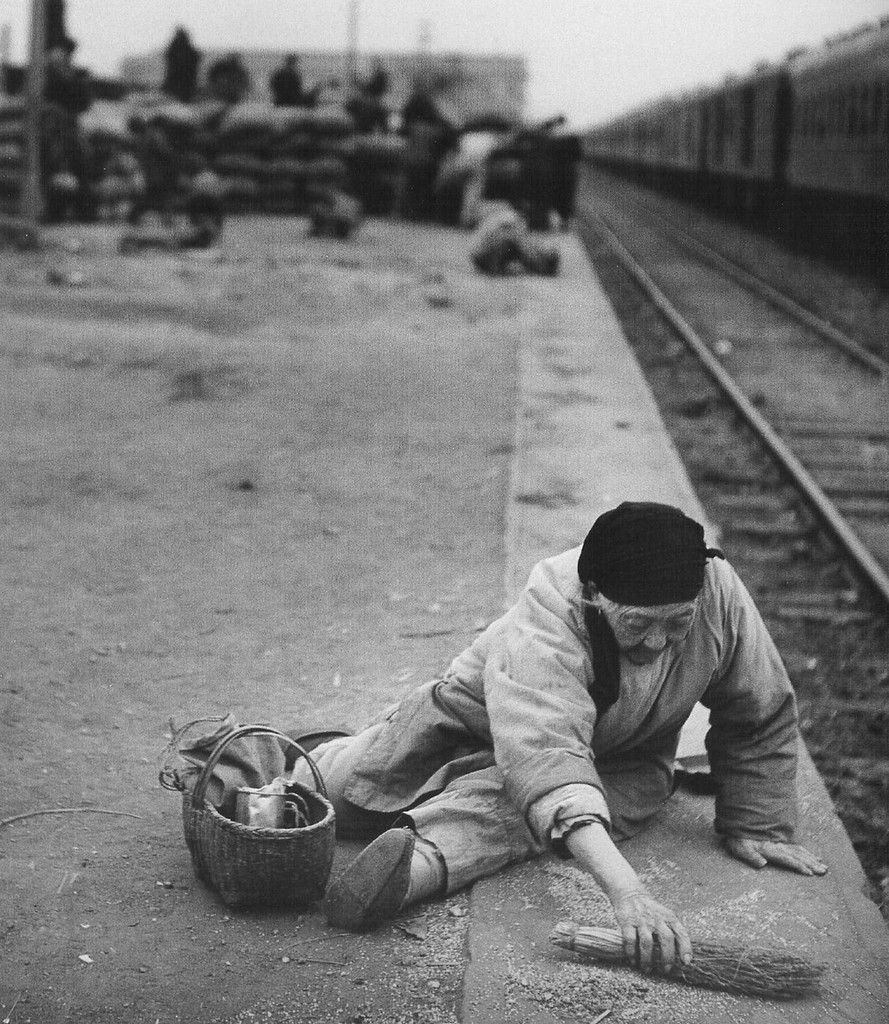

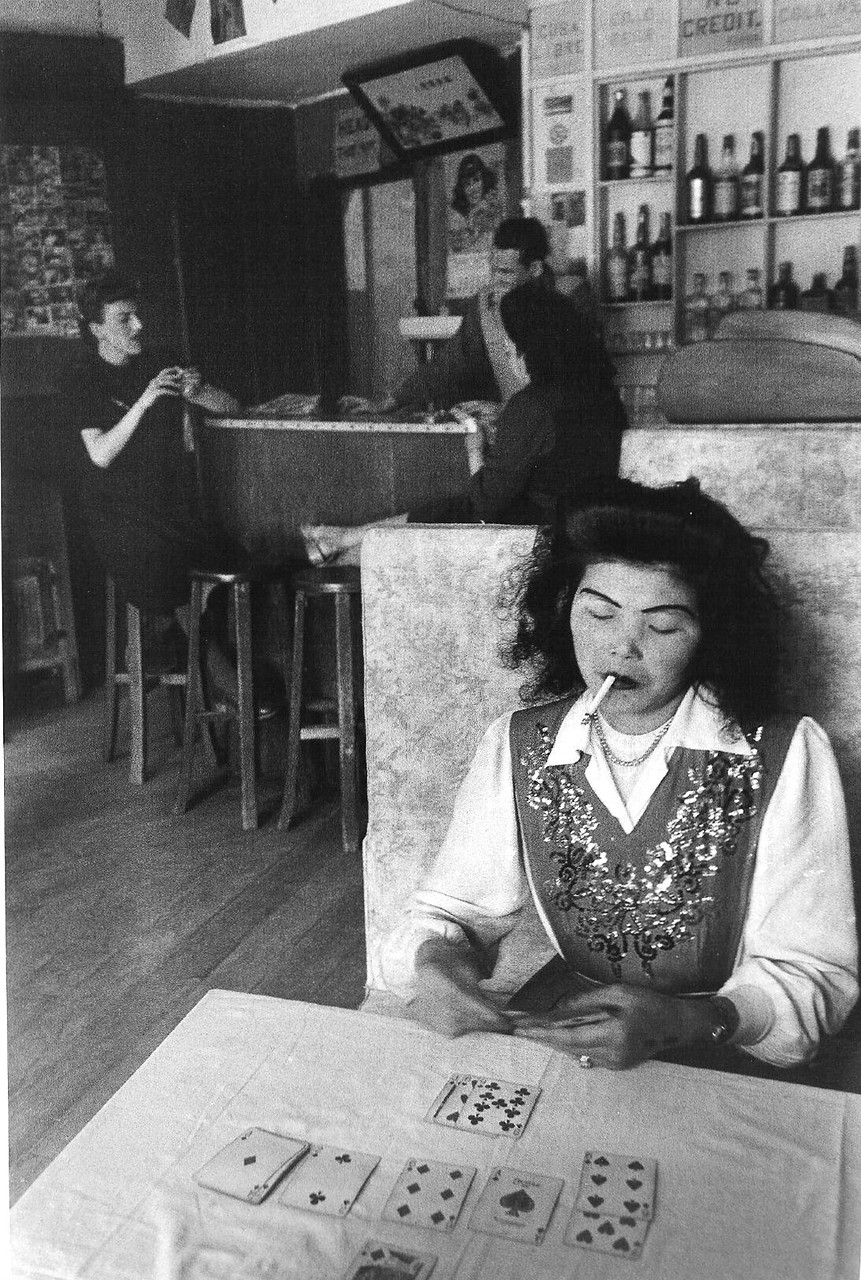

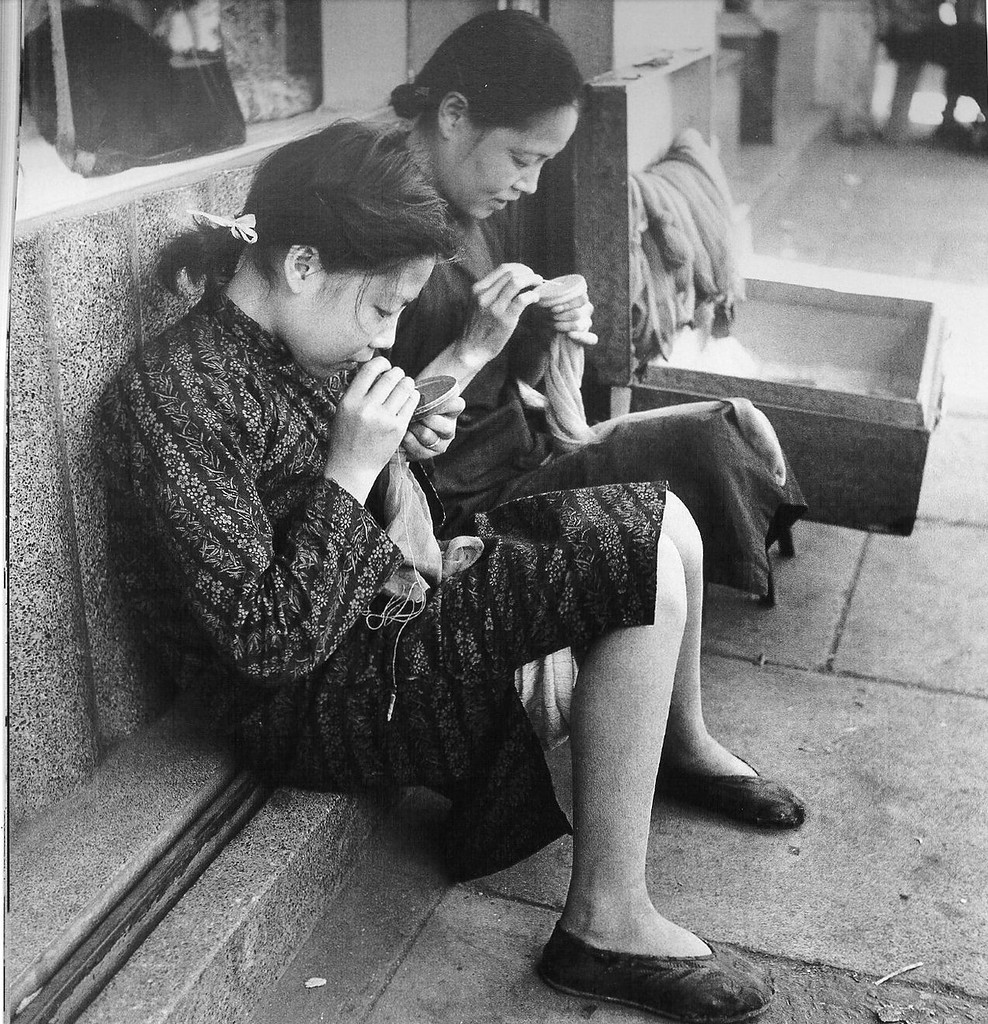

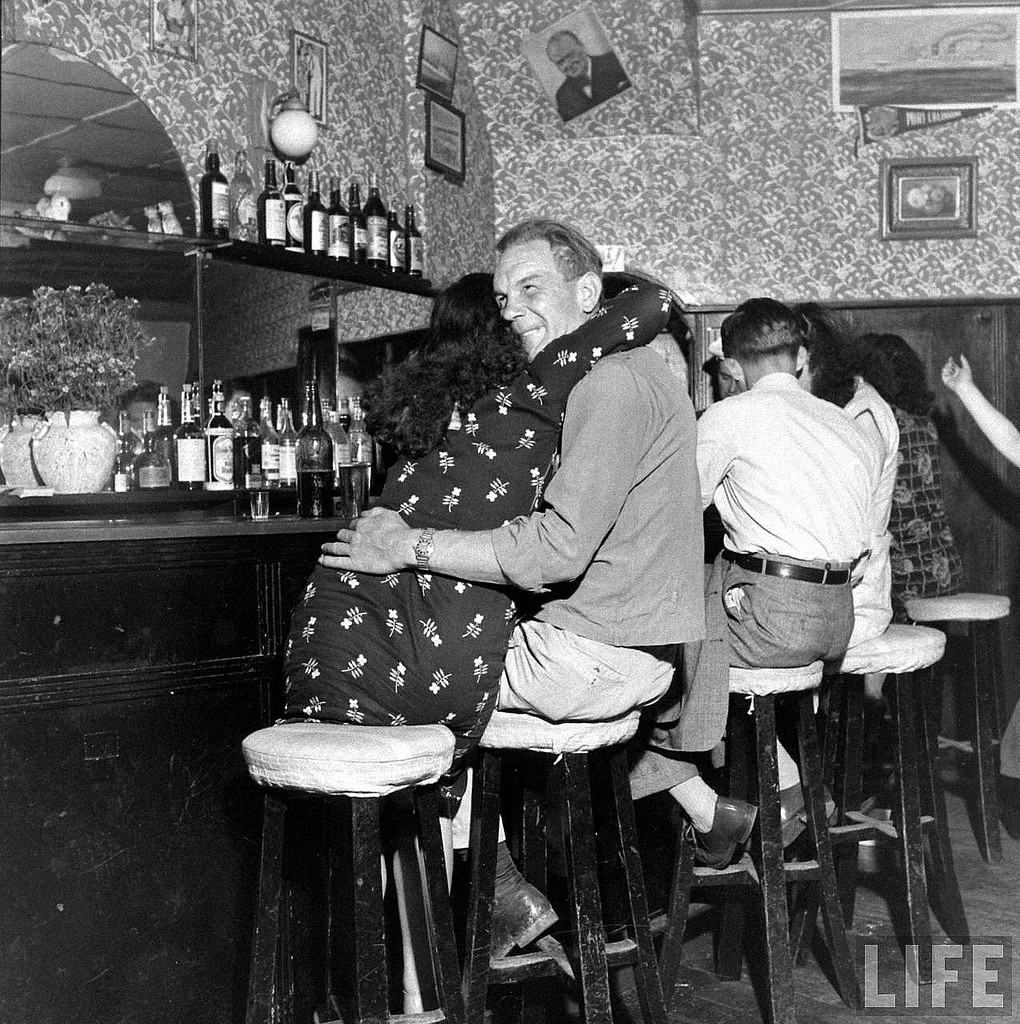

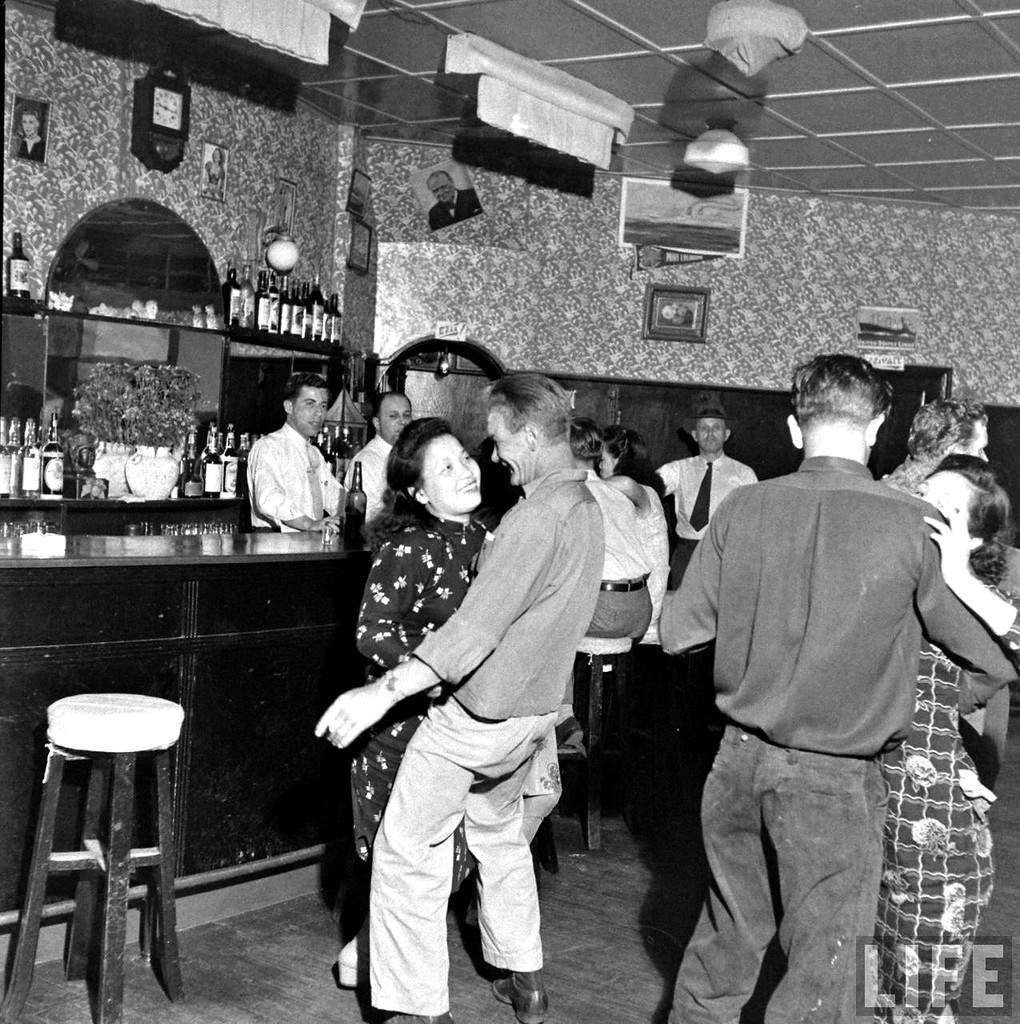

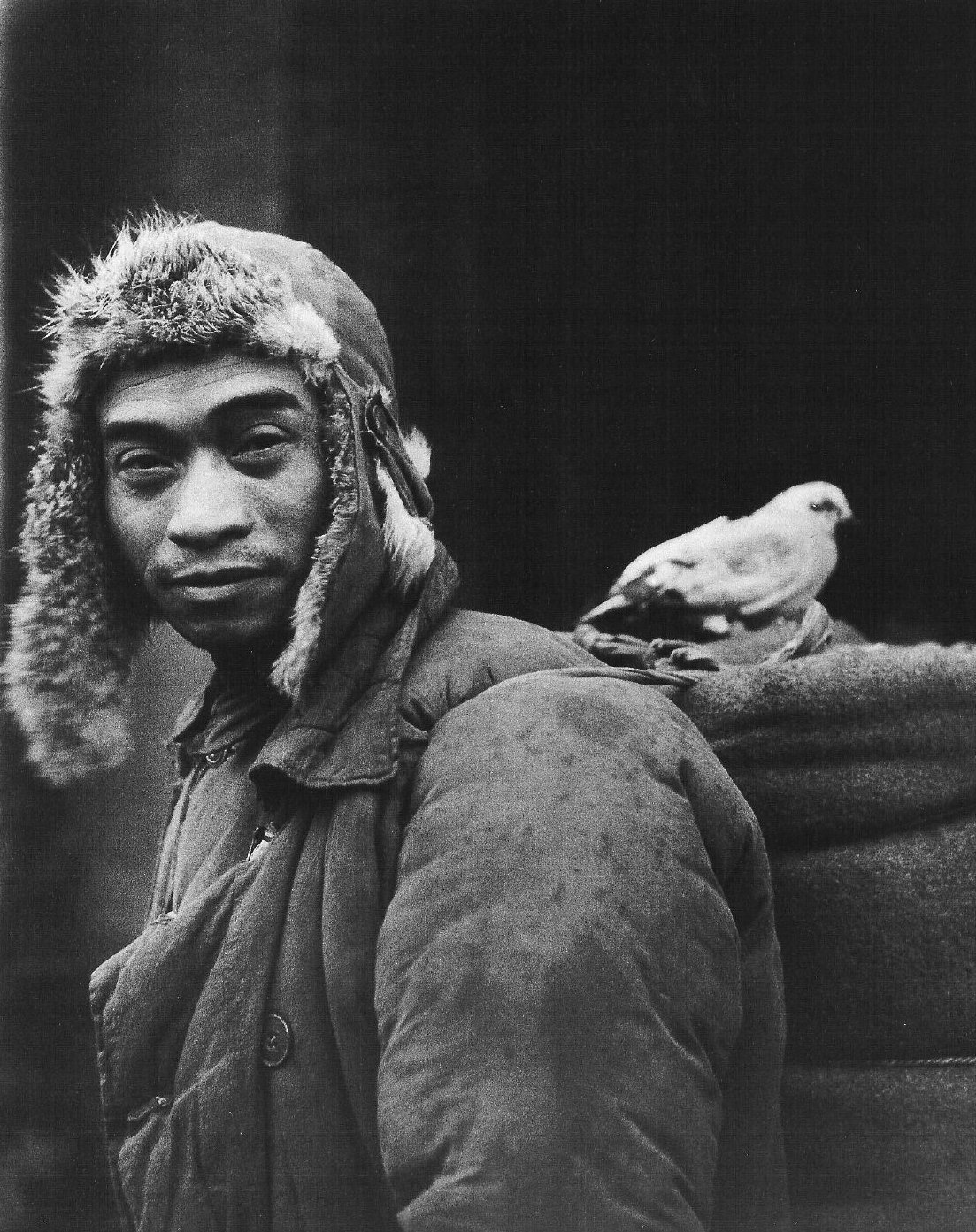

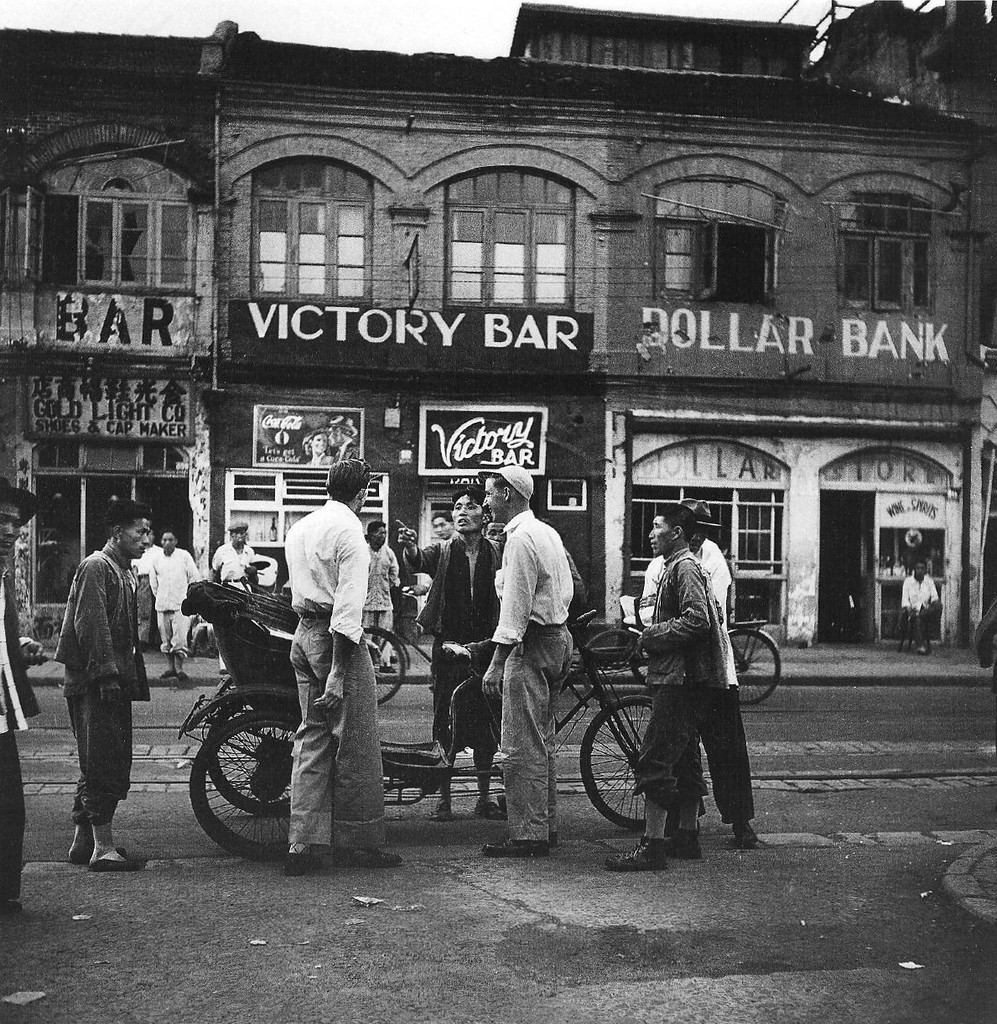

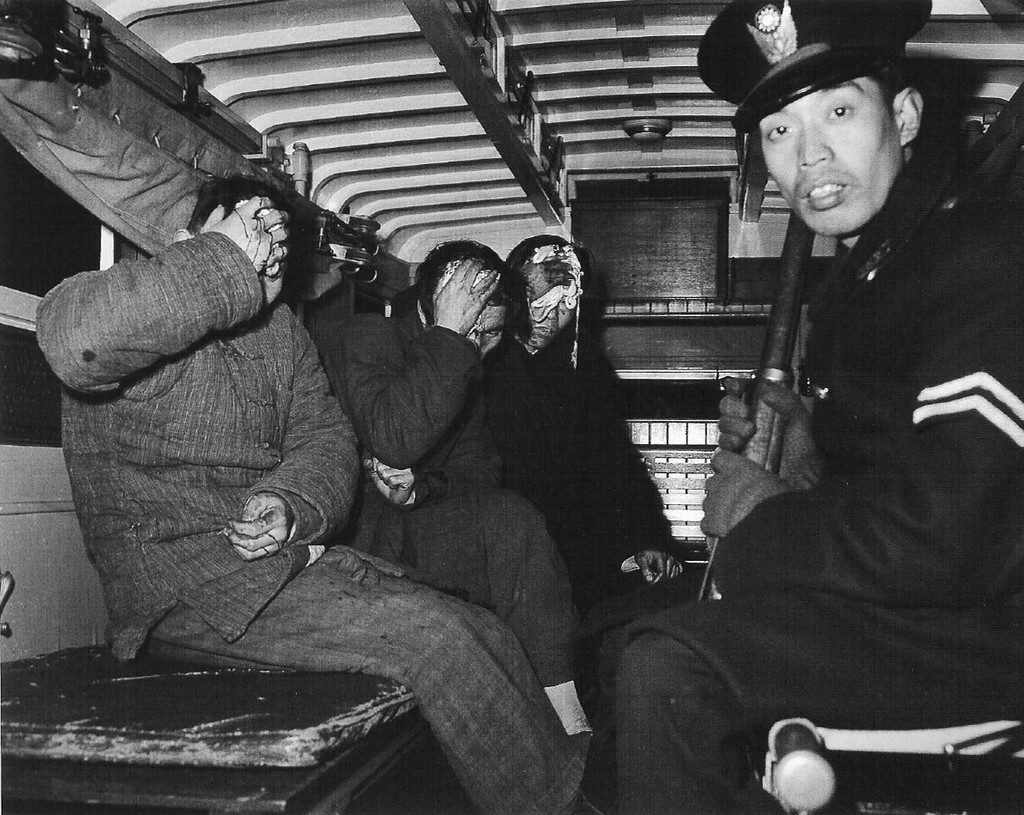

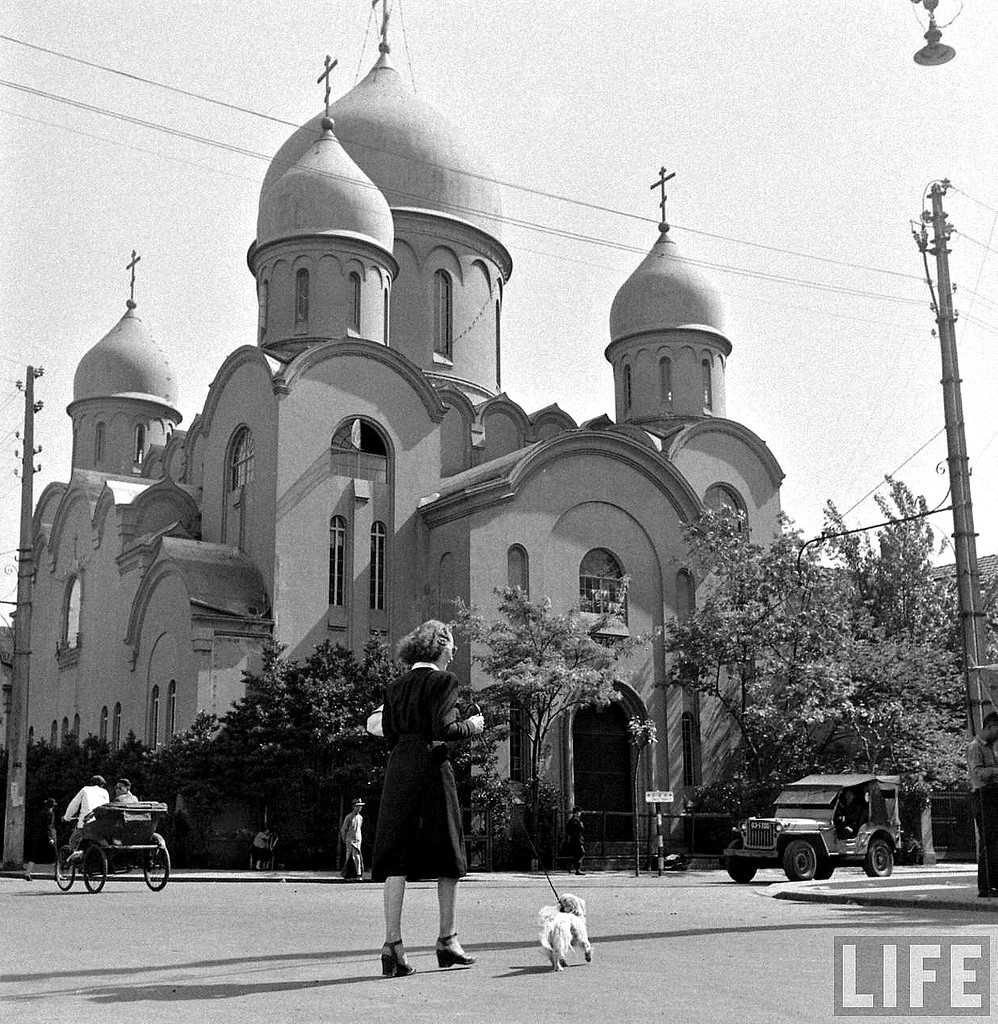

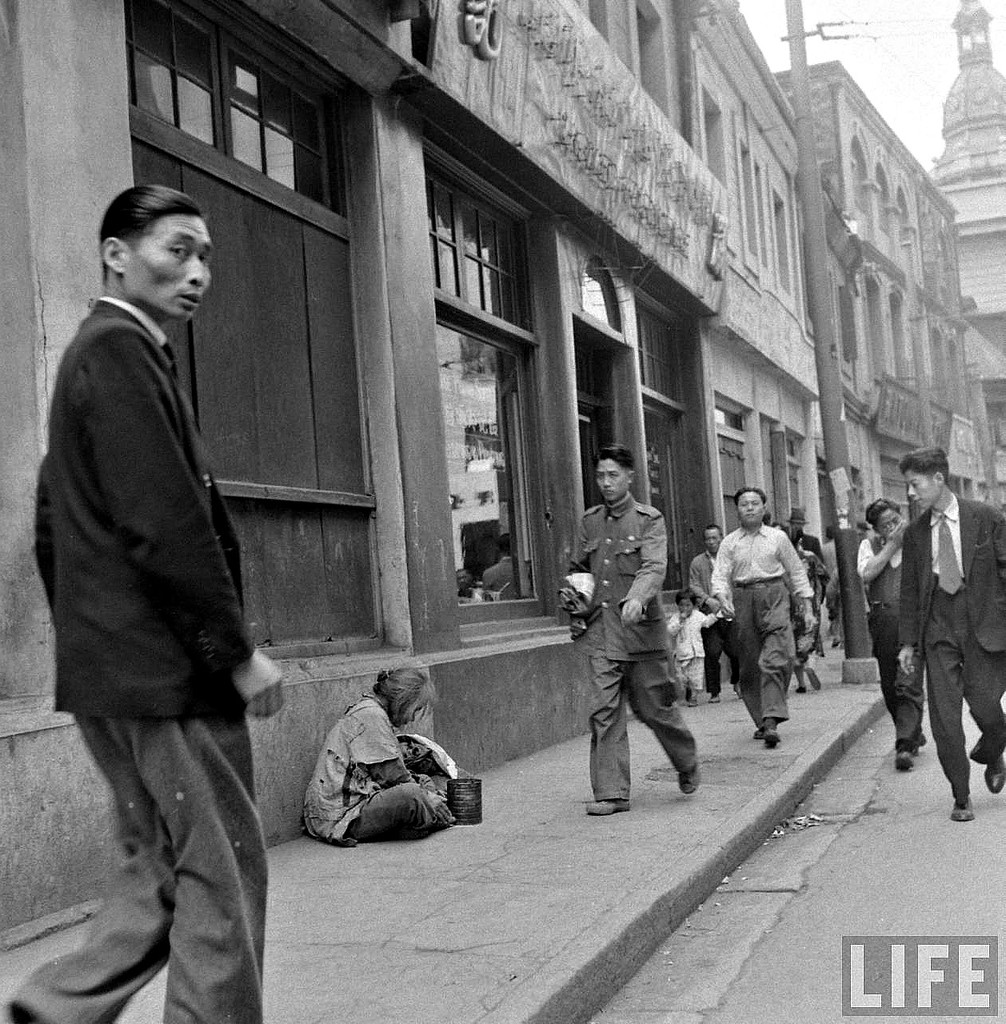

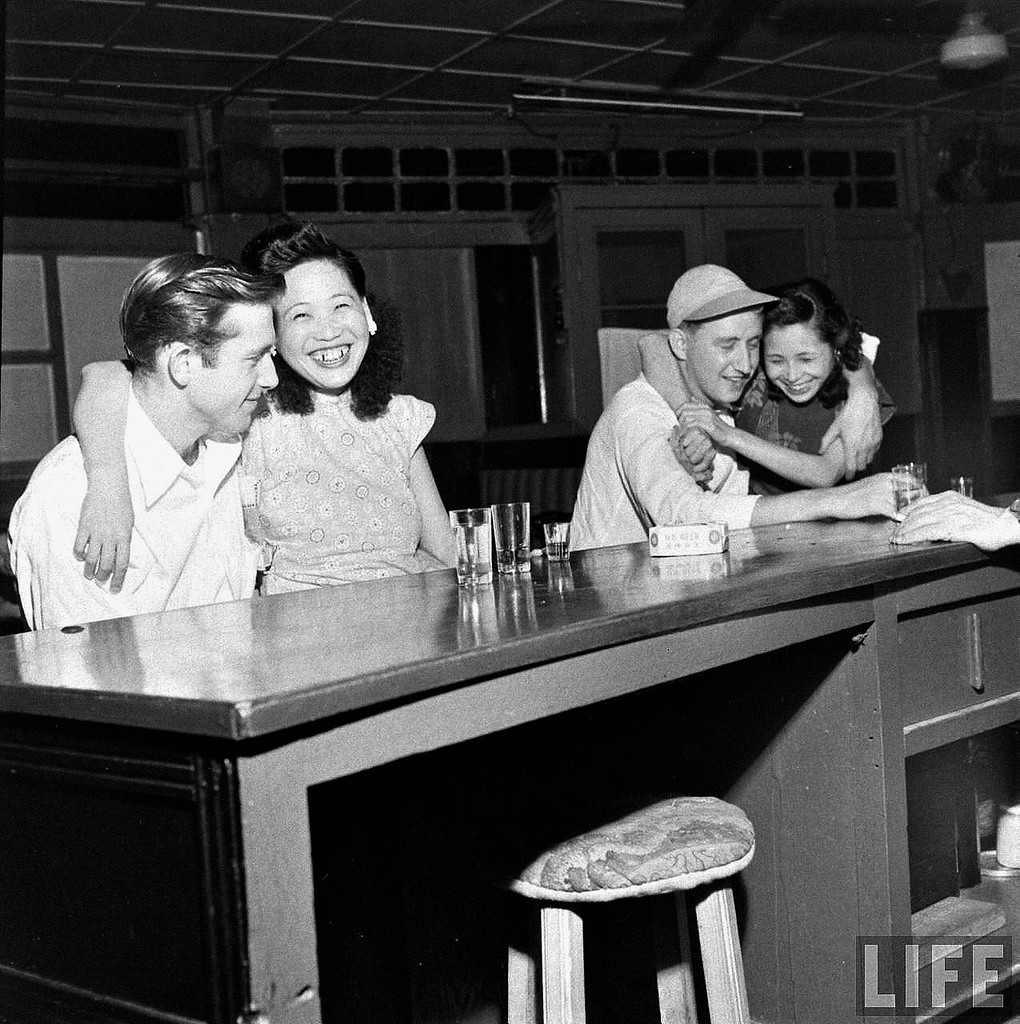

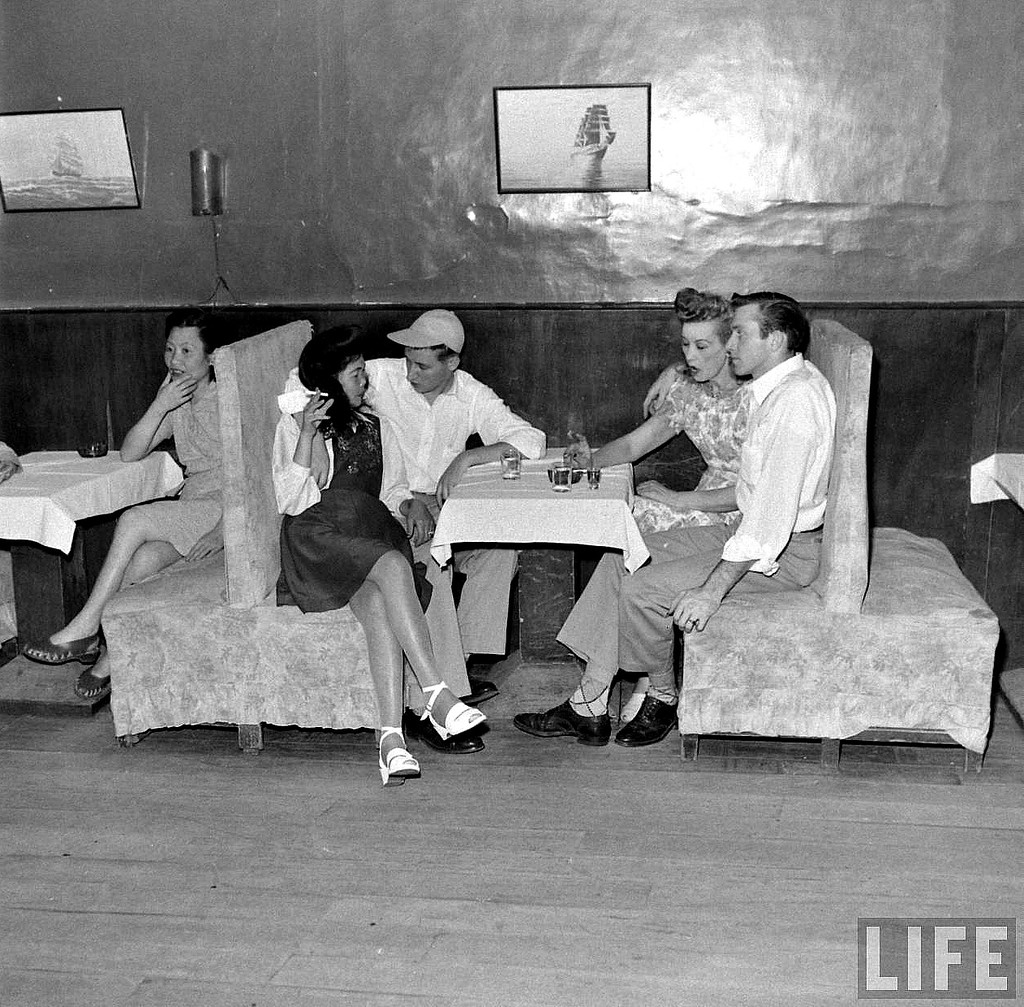

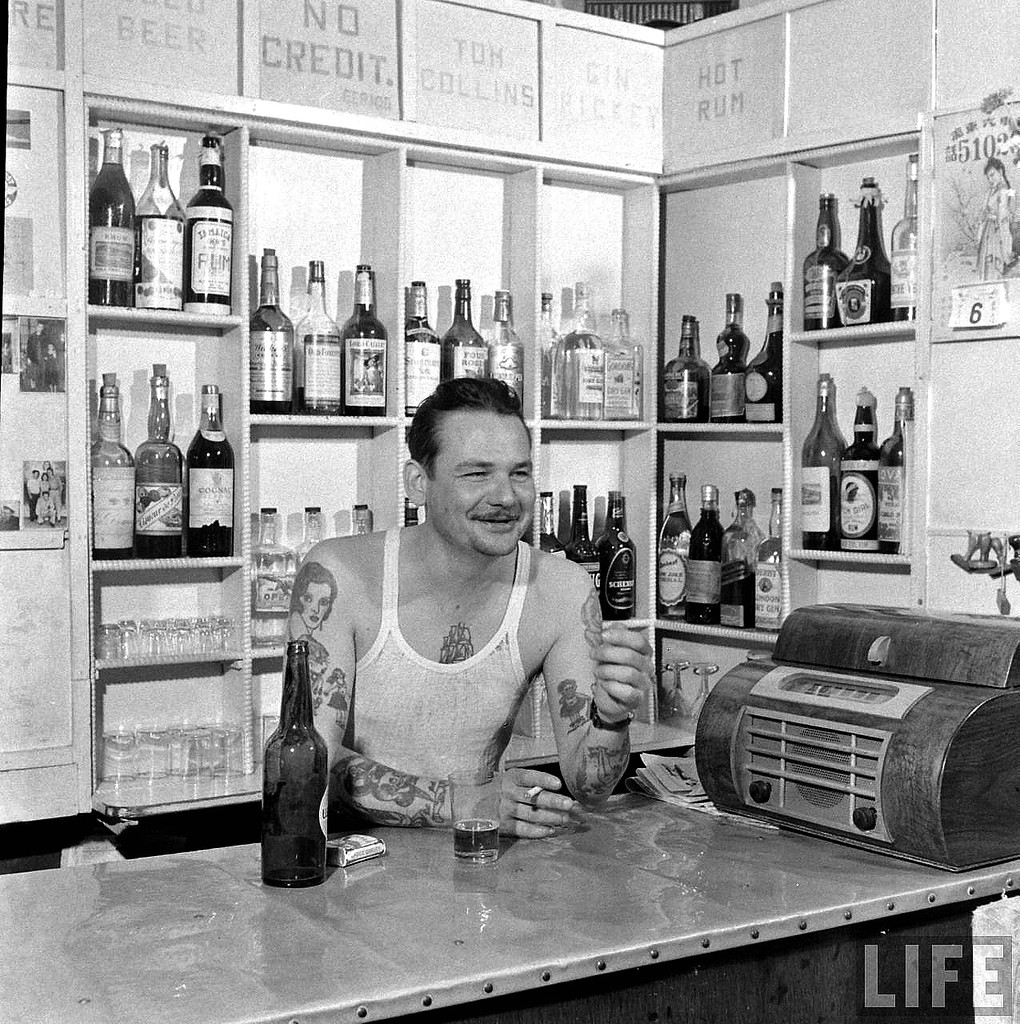

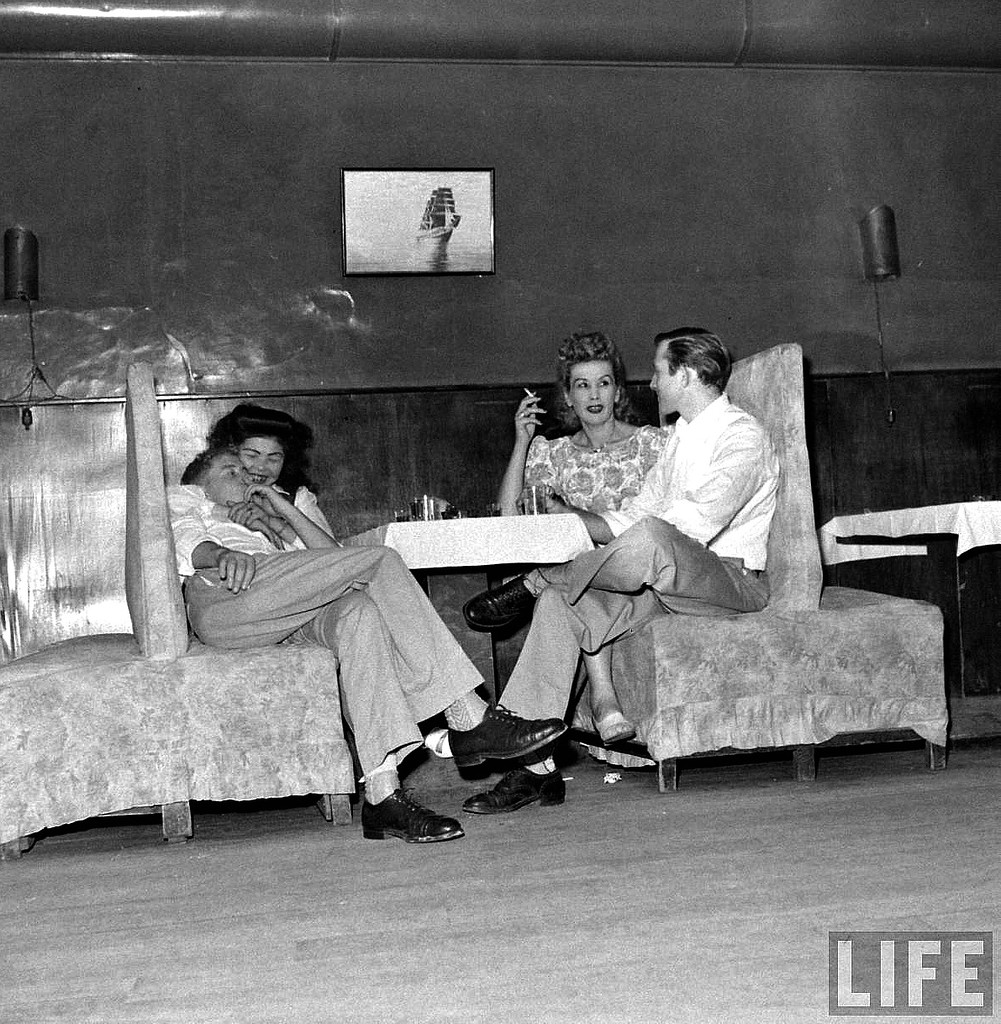

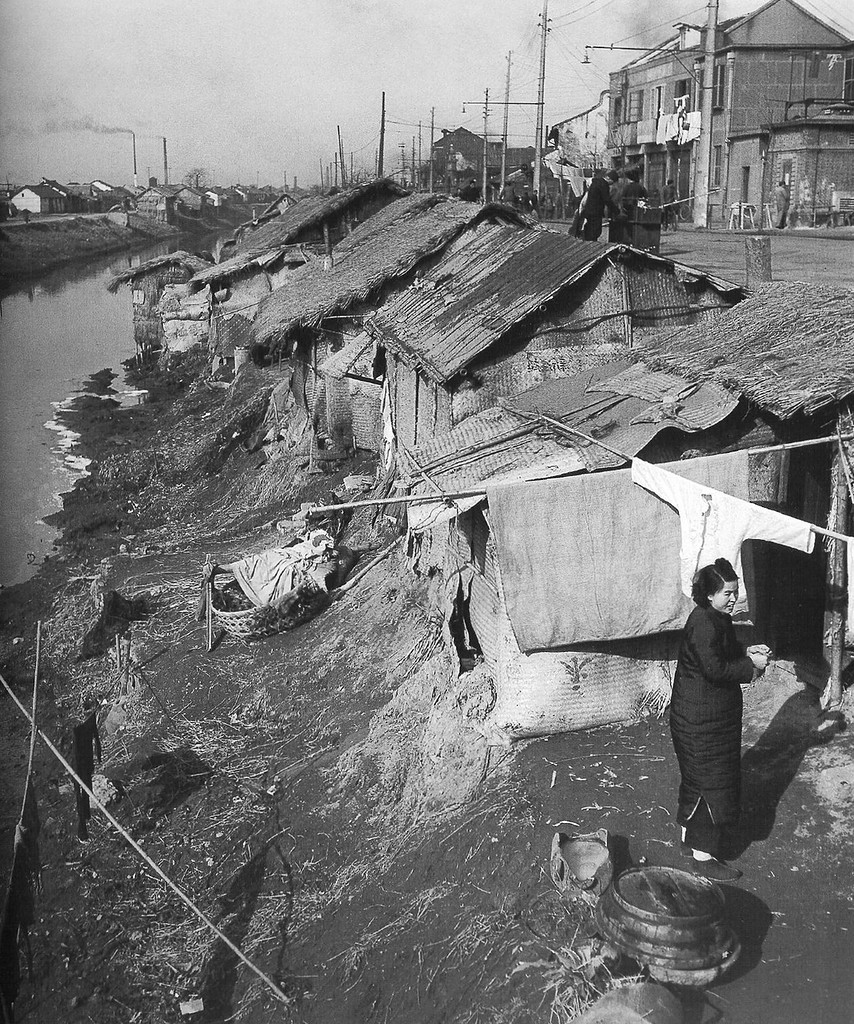

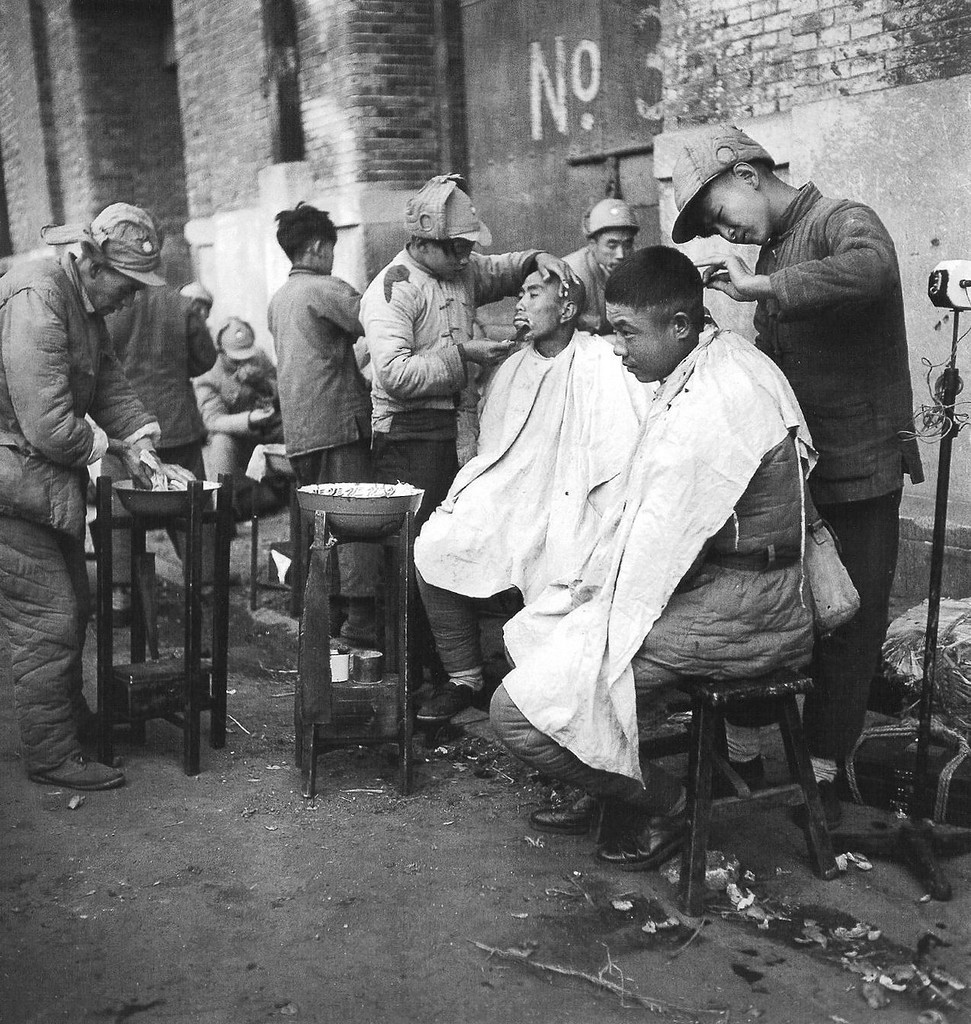

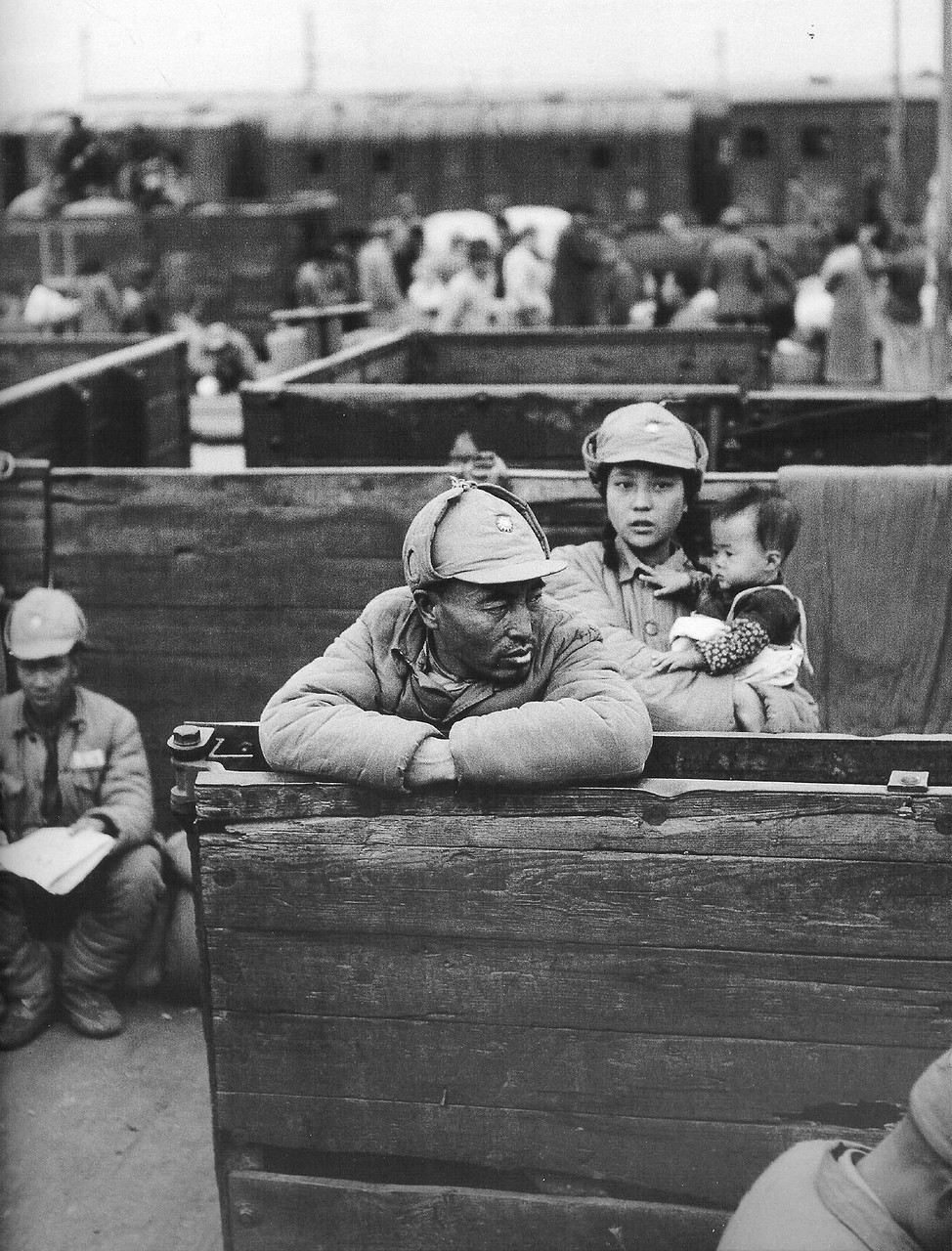

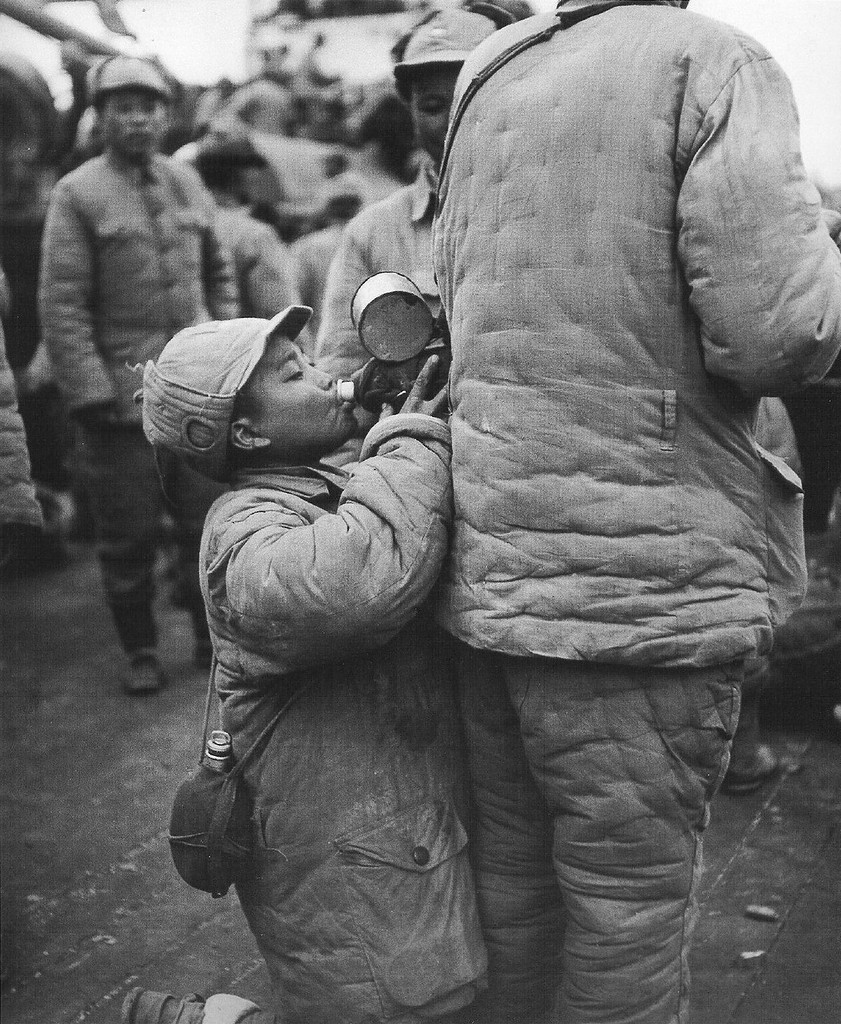

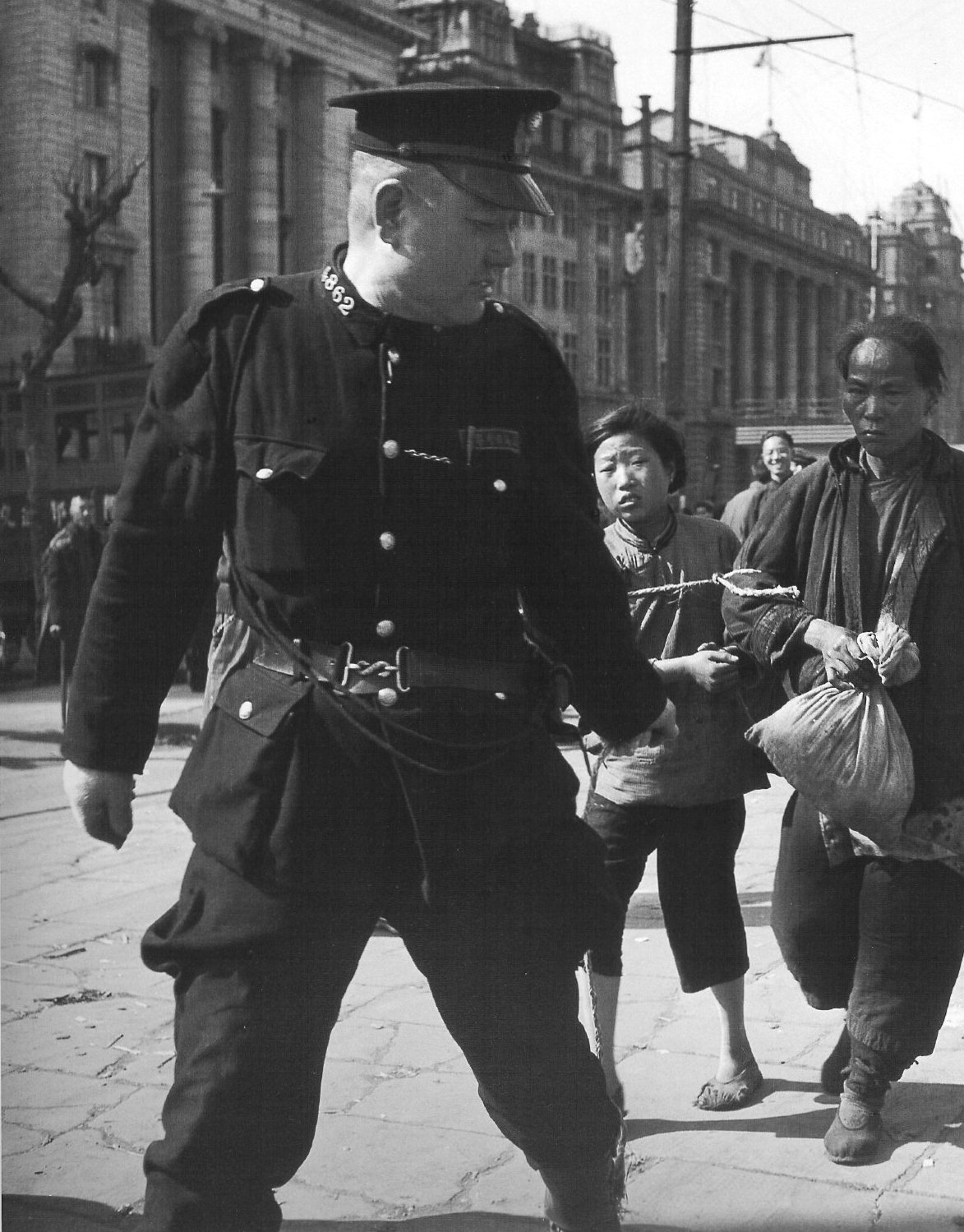

The images were taken by photographer Jack Birns, who was sent to China to take pictures and document what was happening in Shanghai. What he found was different from expectations – scenes of refugees, prostitutes, soldiers, beggars, street executions, and urban protests. The photos depict a city immersed in Western influences, featuring American neon-lit dive bars at every turn, businesses promoting their offerings in English, and Western expatriate communities navigating daily life amid the challenges of war-torn China. At the time, Shanghai, with a population of six million, held the distinction of being China’s largest city, contributing approximately one-third of the nation’s total GDP. However, despite its economic significance, the nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek faced difficulties in containing the advancing communist forces under Mao Zedong. Even as Mao’s communists gained ground, the streets of nationalist-controlled Shanghai continued to feature Western-style billboards advertising various products, from cigarettes to stockings. In June 1949, there were 32,049 foreigners of more than 50 nationalities in Shanghai. Many foreign countries had more than 1,000 citizens in Shanghai – 3,905 British, 2,547 Americans, 1,442 French, and 1,832 Portuguese. After all these rapid political changes in Shanghai, most British and Americans left the city. The U.S. and some other countries forbade trading and transportation with China, making it tough for foreign companies to stay in Shanghai. The foreign community in Shanghai, a mix of colonial and feudal influences, was in its last phase during the Civil War. Lots of refugees came to Shanghai from the countryside, caught in the fighting between rival armies. Unfortunately, their escape often led to a tough life. The archive’s photo story doesn’t have captions, so we have to guess what Jack Birns’ photos are trying to say. But it feels like he wanted to show a big difference between how Westerners in Shanghai during its last days were doing and how the Chinese people coped in a society getting ready for the new reality. For the most part, it seemed easygoing for the expats until they were told to pack their bags. Meanwhile, Chinese nationalists were left with a much tougher situation, painting a picture of two contrasting experiences during this challenging time. By the time Japan accepted the surrender terms of the Potsdam Declaration on August 14, 1945, China had endured decades of Japanese occupation and eight years of brutal warfare. Millions had perished in combat, and many millions more had died as a result of starvation or disease. Japan’s defeat set off a race between the Nationalists and Communists to control vital resources and population centers in northern China and Manchuria. Nationalist troops, using transportation facilities of the U.S. military, were able to take over key cities and most railway lines in East and North China. Communist troops occupied much of the hinterland in the north and in Manchuria. The Communists gained control of mainland China and proclaimed the People’s Republic of China in 1949, forcing the leadership of the Republic of China to retreat to the island of Taiwan.

(Photo credit: Jack Birns via LIFE Archives / Wikimedia Commons / Britannica). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe