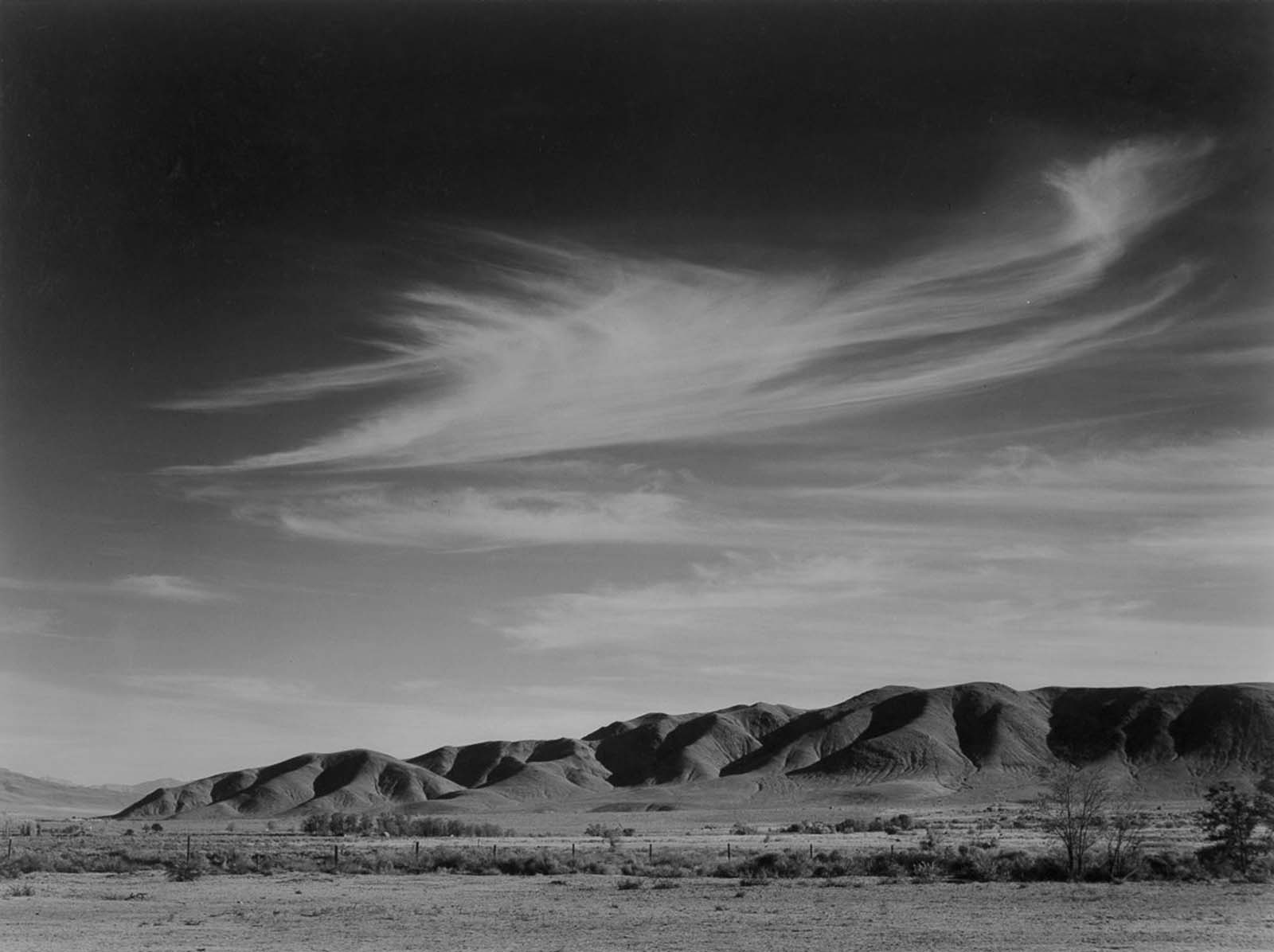

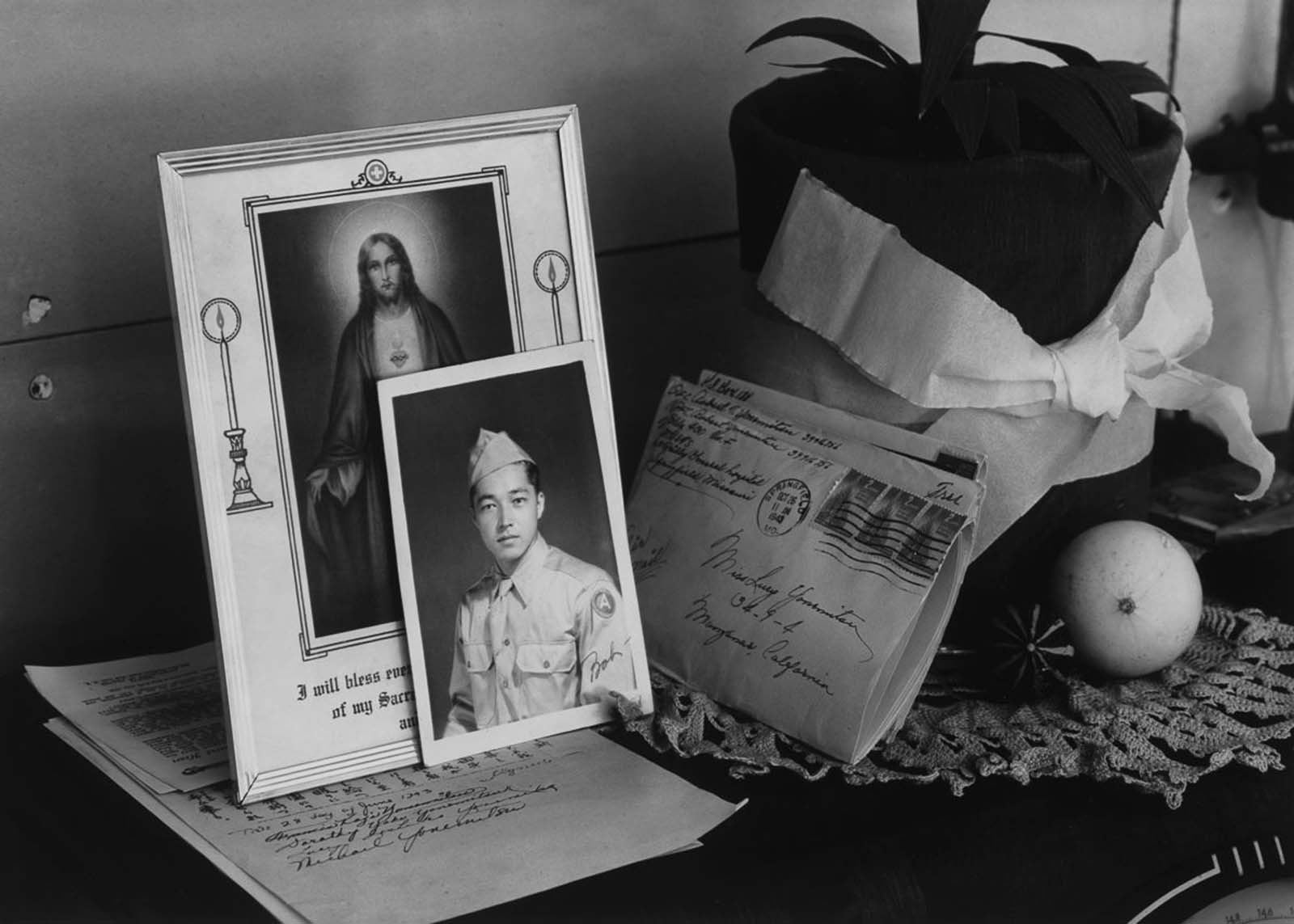

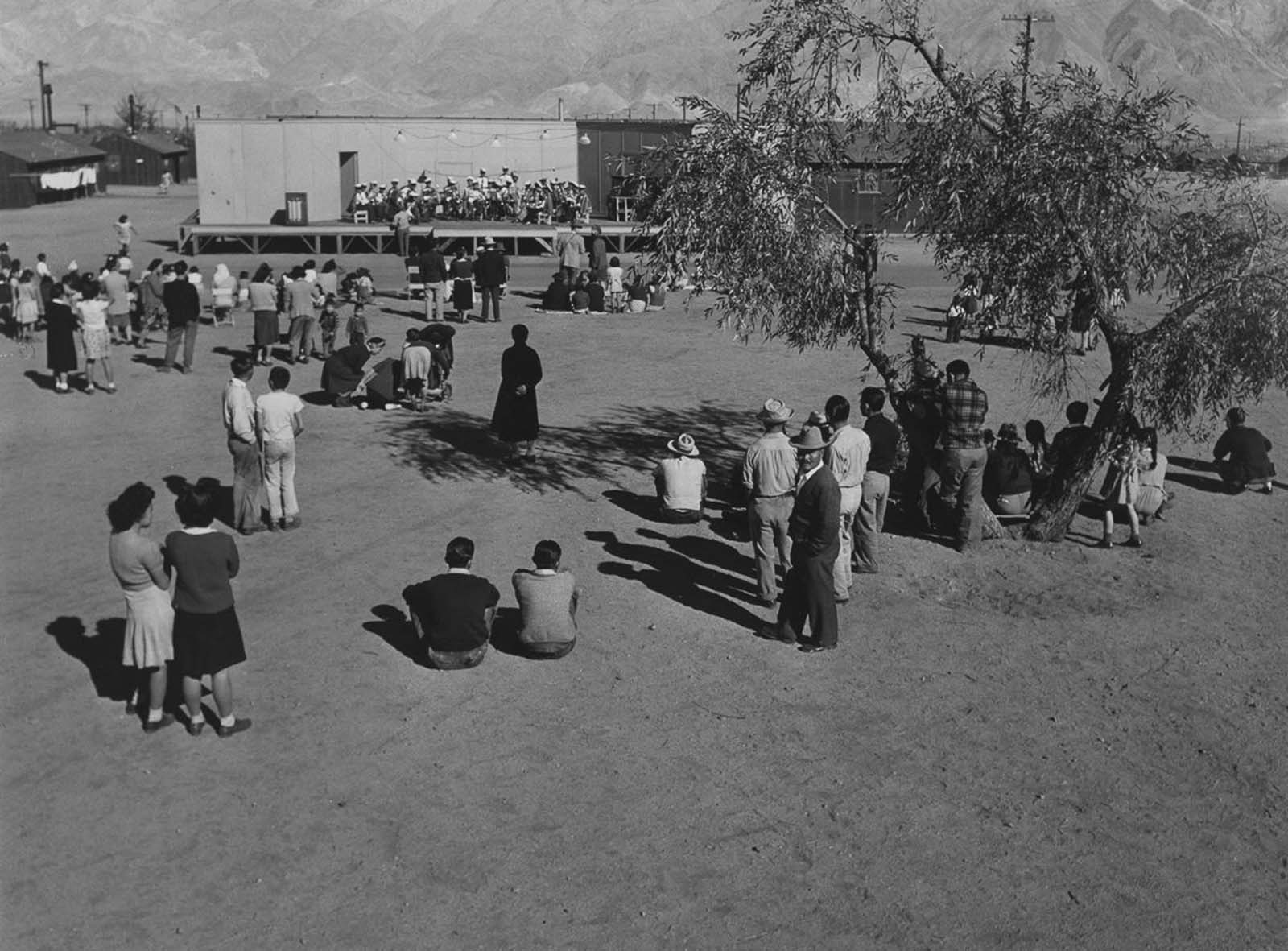

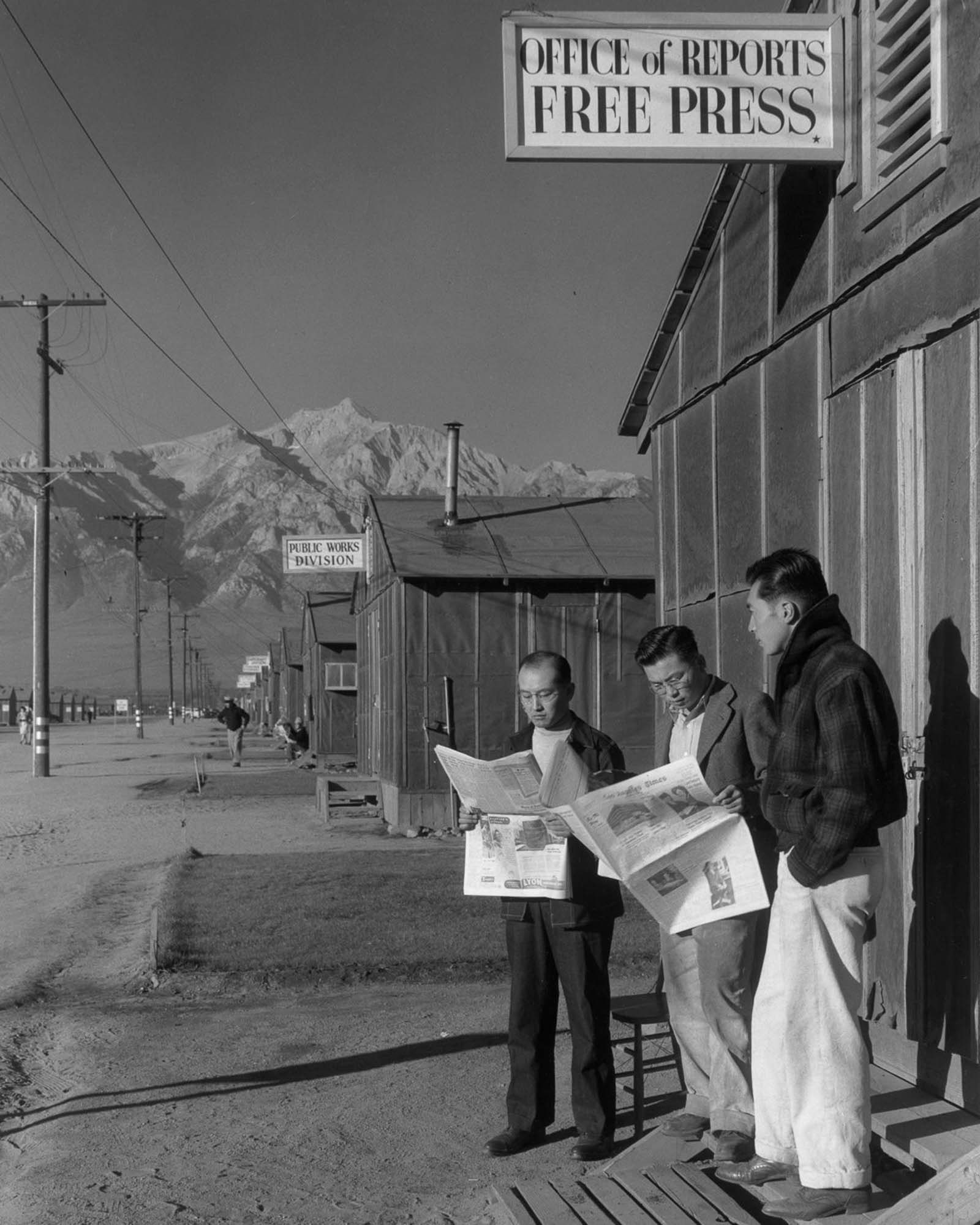

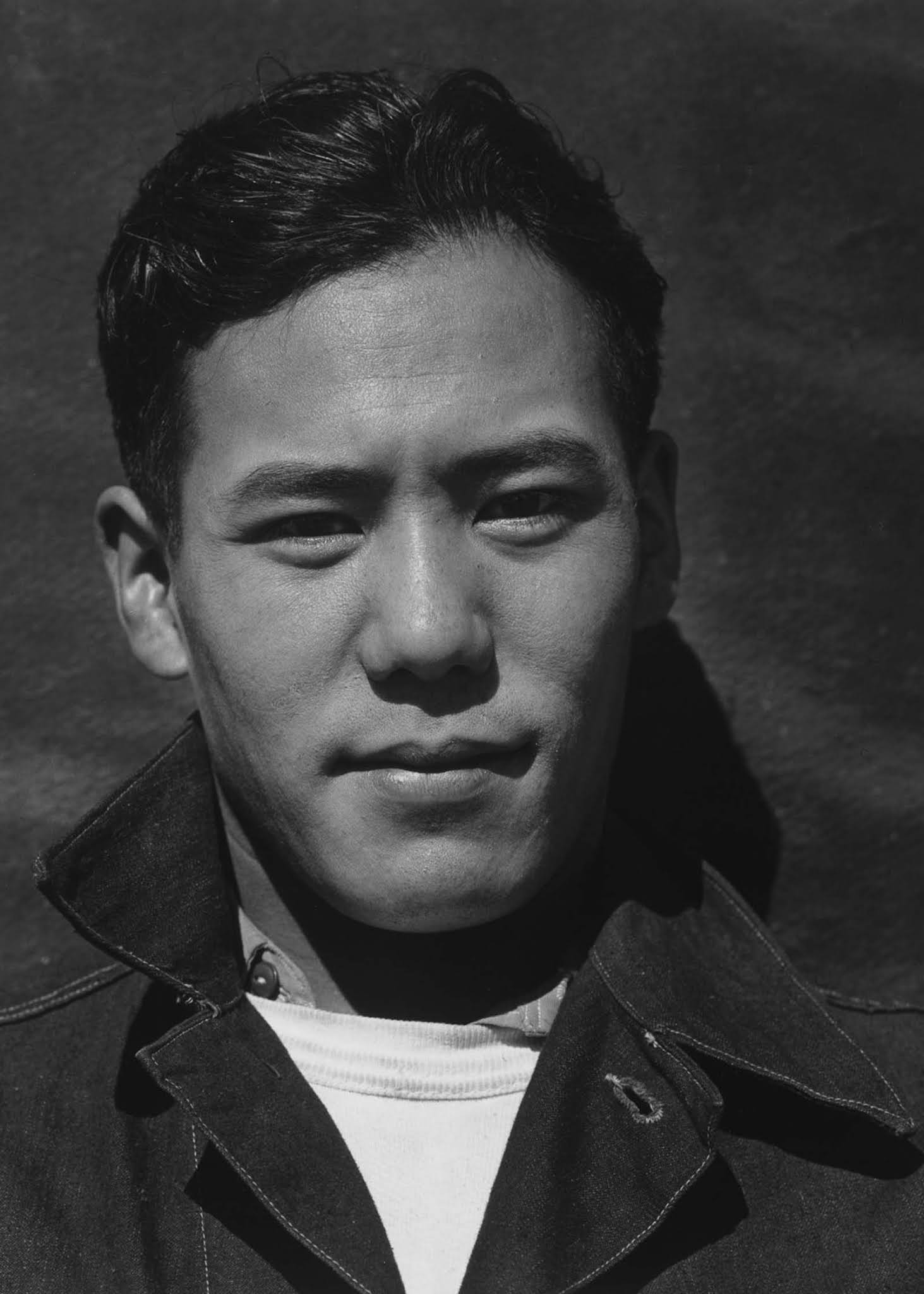

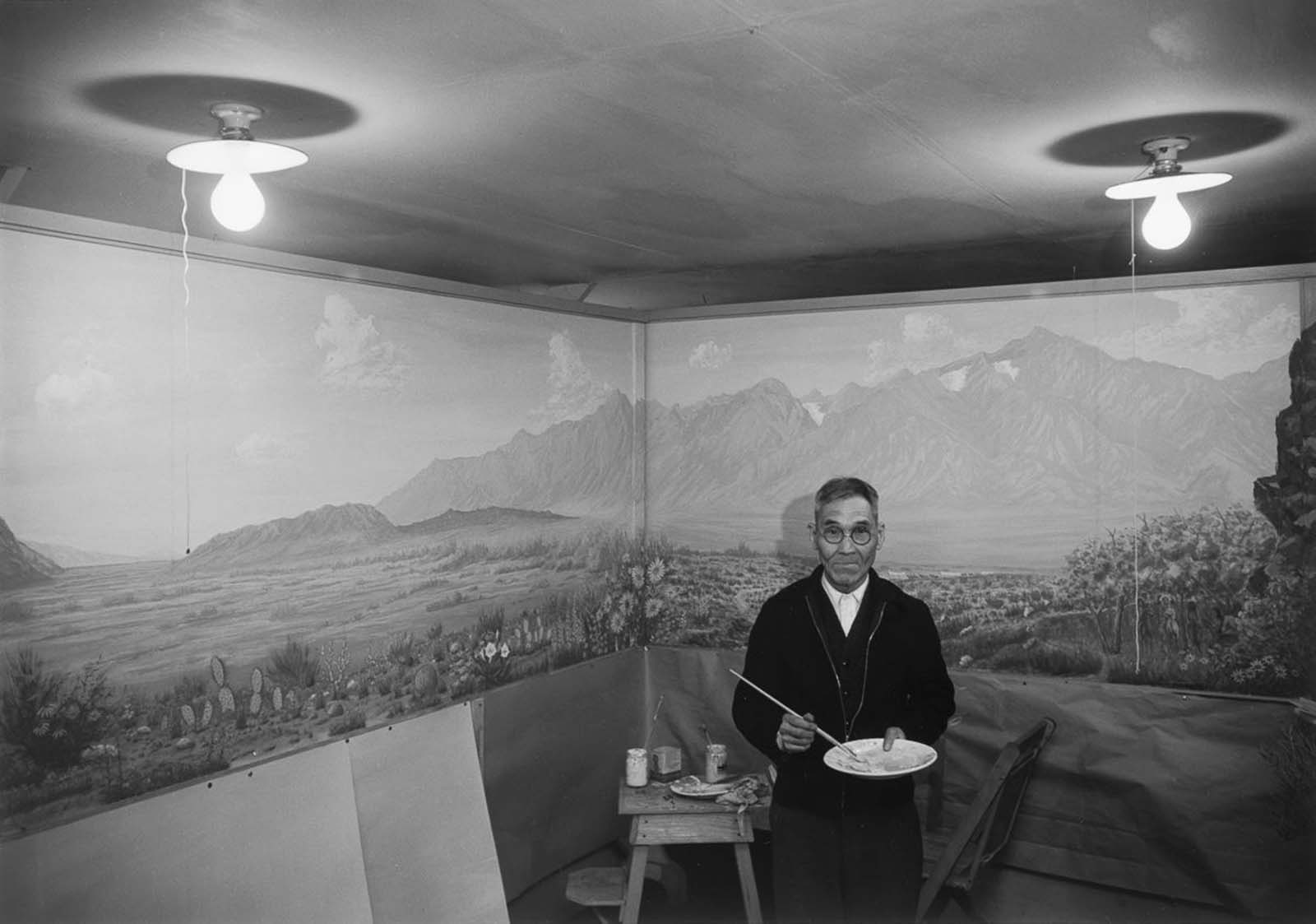

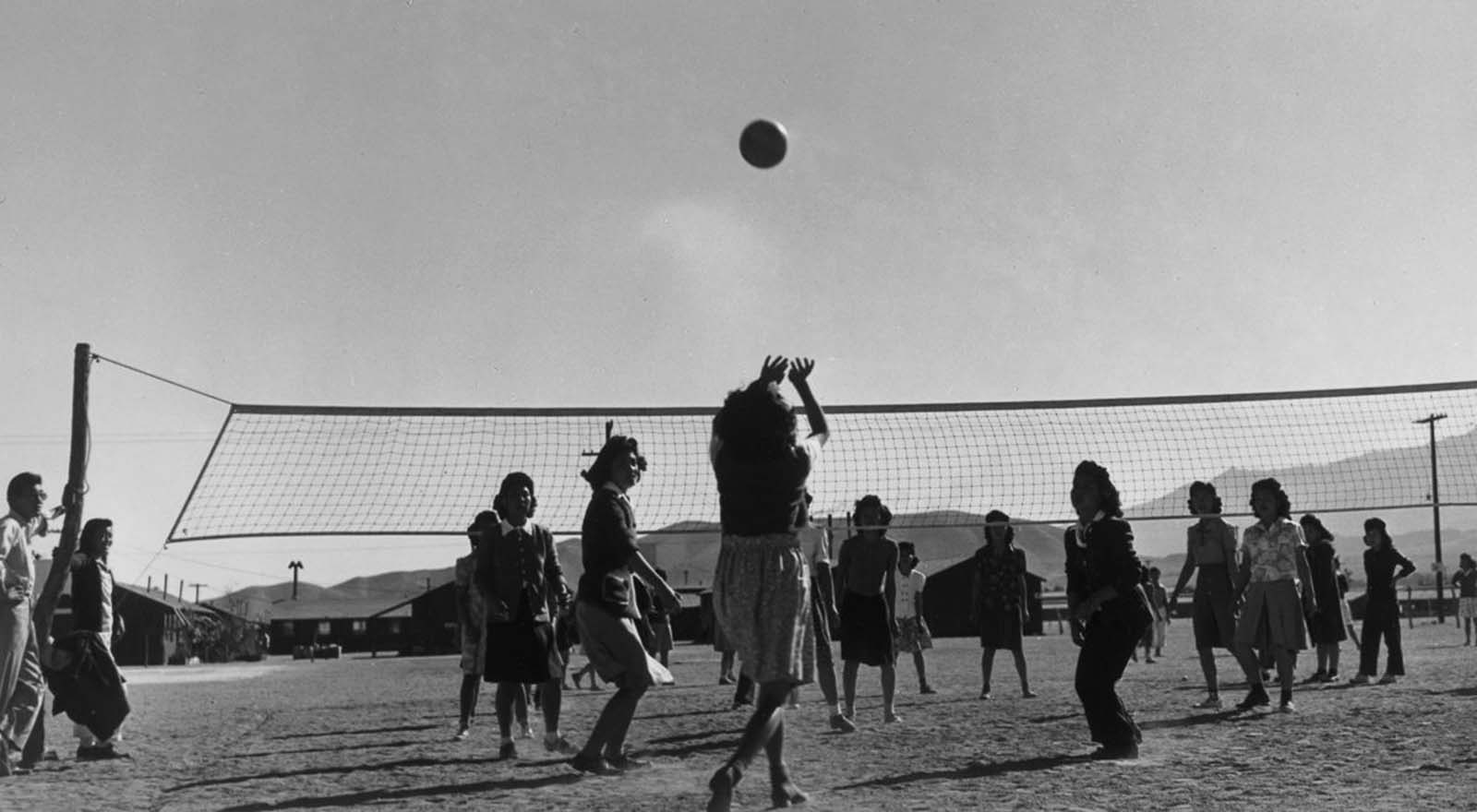

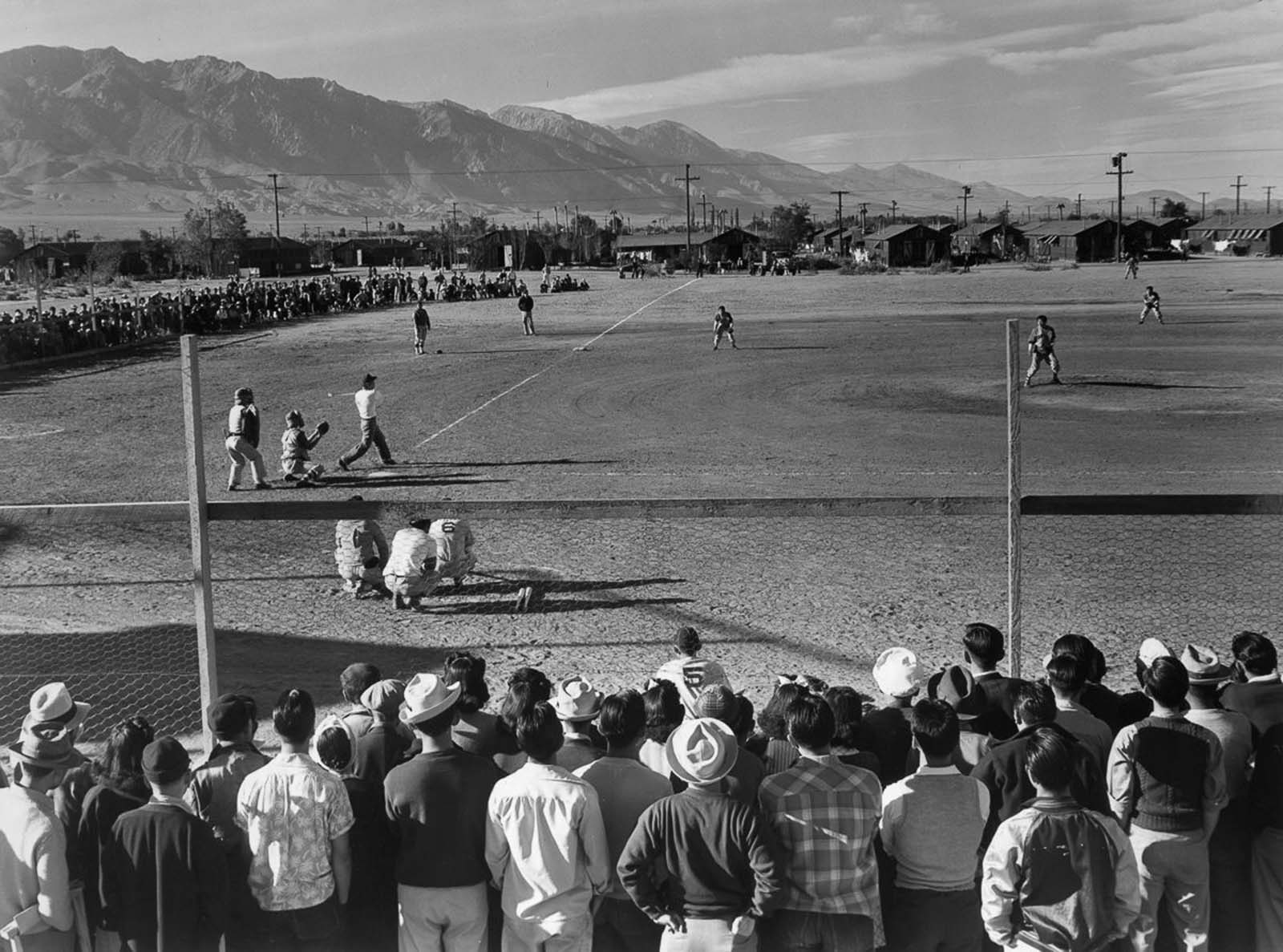

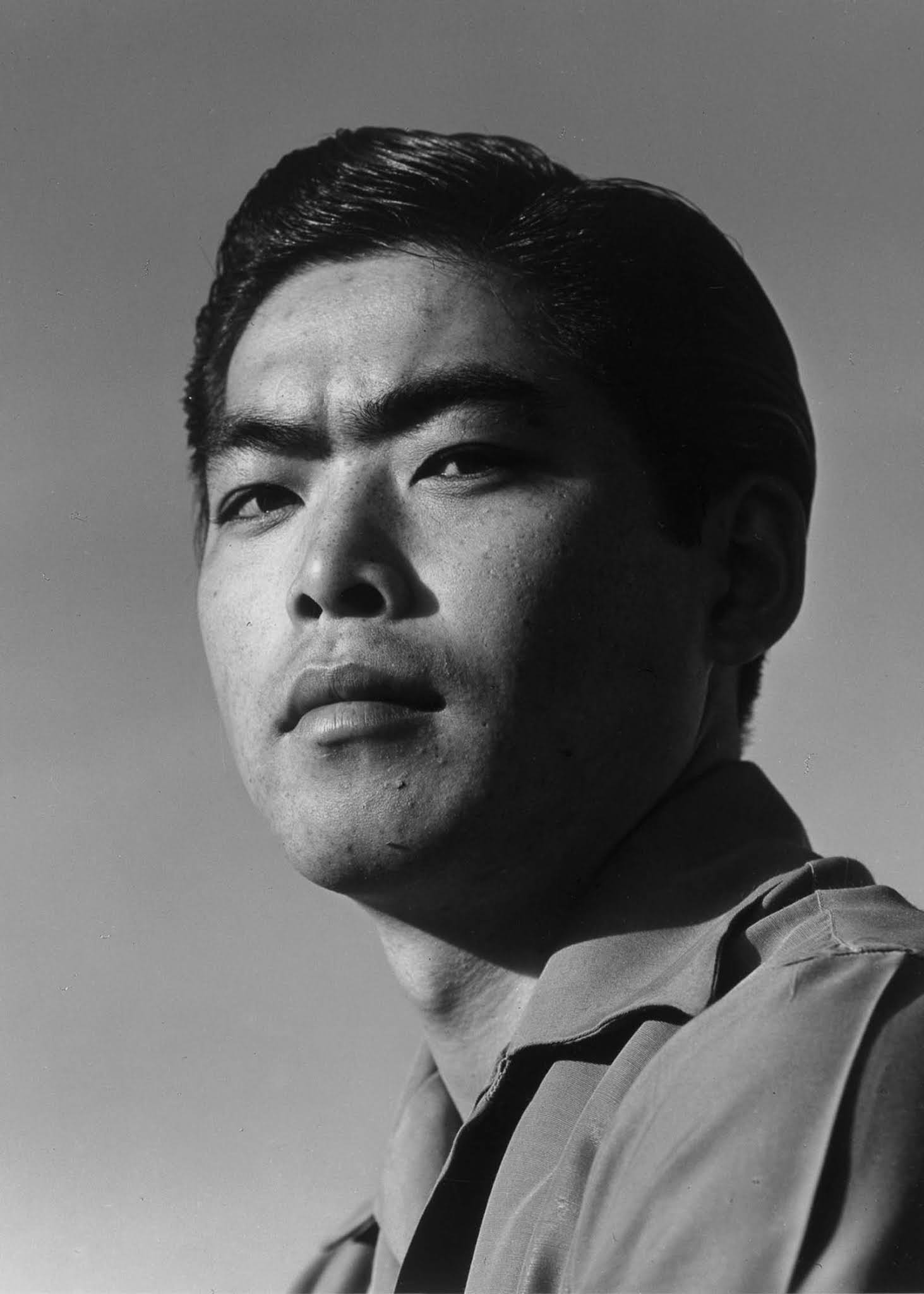

After the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Government swiftly moved to begin solving the “Japanese Problem” on the West Coast of the United States. In the evening hours of that same day, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) arrested selected “enemy” aliens, including more than 5,500 Issei men. Many citizens in California were alarmed about potential activities by people of Japanese descent. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War to designate military commanders to prescribe military areas and to exclude “any or all persons” from such areas. The order also authorized the construction of what were later called “relocation centers” by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), to house those who were to be excluded. This order resulted in the forced relocation of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were native-born American citizens; the rest had been prevented from becoming citizens by federal law. Over 110,000 were incarcerated in the ten concentration camps located far inland and away from the coast. Without due process, the government gave everyone of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast only days to decide what to do with their houses, farms, businesses, and other possessions. Most families sold their belongings at a significant loss. Some rented their properties to neighbors. Others left possessions with friends or religious groups. Some abandoned their property. They did not know where they were going or for how long. Each family was assigned an identification number and loaded into cars, buses, trucks, and trains, taking only what they could carry. The Manzanar concentration camp was situated on 6,200 acres (2,500 ha) at Manzanar, leased from the City of Los Angeles, with the developed portion covering approximately 540 acres (220 ha). Eight guard towers equipped with machine guns were located at intervals around the perimeter fence, which was topped by barbed wire. The grid layout used in the camp was standard, and a similar layout was used in all of the relocation centers. The residential area was about one square mile (2.6 km2) and consisted of 36 blocks of hastily constructed, 20-foot (6.1 m) by 100-foot (30 m) tarpaper barracks, with each family (up to eight people) living in a single 20-foot (6.1 m) by 25-foot (7.6 m) “apartment” in the barracks. These apartments consisted of partitions with no ceilings, eliminating any chance of privacy. Lack of privacy was a major problem, especially since the camp had communal men’s and women’s latrines. The camp had school facilities, a high-school auditorium (that was also used as a theatre), staff housing, chicken and hog farms, churches, a cemetery, a post office, a hospital, an orphanage, two community latrines, an outdoor theater, and other necessary amenities that one would expect to find in most American cities. Some of the facilities were not built until after the camp had been operating for a while. The camp perimeter had eight watchtowers manned by armed military police, and it was enclosed by five-strand barbed wire. There were sentry posts at the main entrance. Many of the camp administration staff lived inside the fence at the camp, though the military police lived outside the fence. Each American concentration camp was intended to be self-sufficient, and Manzanar was no exception. Cooperatives operated various services, such as the camp newspaper, beauty salons and barber shops, shoe repair, libraries, and more. In addition, there were some who raised chickens, hogs, and vegetables and cultivated the existing orchards for fruit. During the time Manzanar was in operation, 188 weddings were held, 541 children were born in the camp, and between 135 and 146 individuals died. Some of those interned at the camp supported the policies implemented by War Relocation Authority, causing them to be targeted by others in the camp. On December 6, 1942, a riot broke out and two internees were killed. Togo Tanaka was one of those targeted, but he escaped by disguising himself and mingling into the crowd that was searching for him. Others were outraged that their patriotism was being questioned simply because of their ethnic heritage. Despite the hardships endured, the internees gradually “turned [the] concentration camp into a community” by “[spending] their days creating beautiful things”. Most of the adults were employed at Manzanar to keep the camp running. In order for the camps to be self-sufficient, the adults were employed in a variety of jobs to supply the camp and the military. Jobs included clothing and furniture manufacturing, farming and tending orchards, military manufacturing such as camouflage netting and experimental rubber, teaching, civil service jobs such as police, firefighters, and nursing, and general service jobs operating stores, beauty parlors, and a bank. A farm and orchards provided vegetables and fruits for use by the camp, and people of all ages worked to maintain them. By the summer of 1943, camp gardens and farms were producing potatoes, onions, cucumbers, Chinese cabbage, watermelon, eggplant, tomatoes, aster, red radishes, and peppers. Eventually, there were more than 400 acres of farms producing more than 80 percent of the produce used by the camp. In early 1944, a chicken ranch began operation, and in late April of the same year, the camp opened a hog farm. Both operations provided welcome meat supplements to the diet. A total of 11,070 Japanese Americans were processed through Manzanar. From a peak of 10,046 in September 1942, the population dwindled to 6,000 by 1944. The last few hundred internees left in November 1945, three months after the war ended. Many of them had spent three-and-a-half years at Manzanar. Between one hundred thirty-five and one hundred forty-six Japanese Americans died at Manzanar. Fifteen were buried there, but only five graves remain, as most were reburied elsewhere by their families. The Manzanar cemetery site is marked by a monument that was built by stonemason Ryozo Kado in 1943. An inscription in Japanese on the front (east side) of the monument reads 慰霊塔 (“Soul Consoling Tower”). The inscription on the back (west side) reads “Erected by the Manzanar Japanese” on the left-hand column, and “August 1943” on the right-hand column. The removal of all Japanese Americans from the West Coast was based on widespread distrust of their loyalty after Pearl Harbor. Yet, no Japanese Americans were charged with espionage. In 1988, Congress passed legislation apologizing for the “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership” which caused the internments, and called for the disbursement of reparations to the victims. The survivors and heirs of survivors ultimately received $1.6 billion as redress for their unconstitutional internment. (Photo credit: Ansel Adams / Library of Congress / Wikipedia / NPS.gov). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe