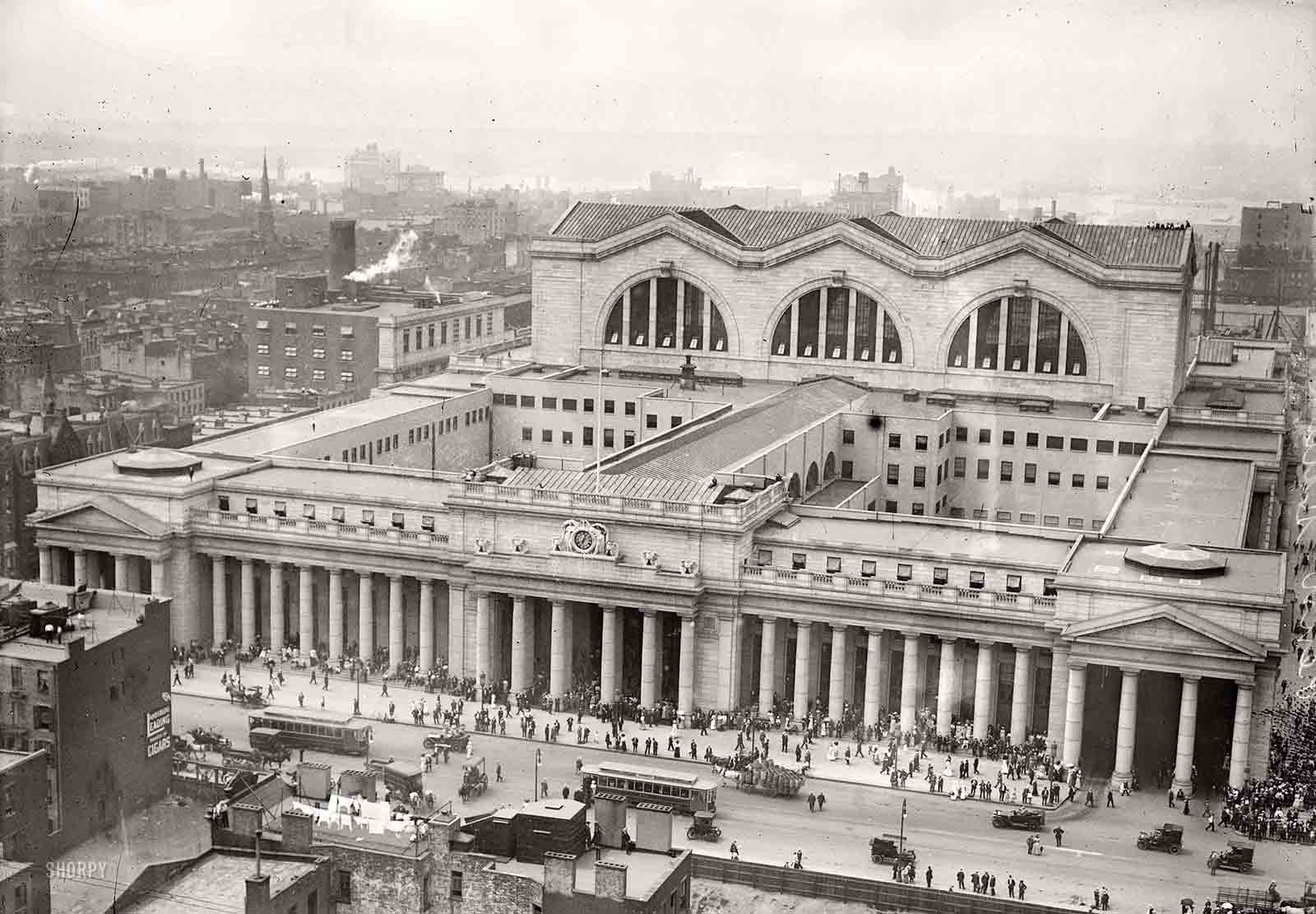

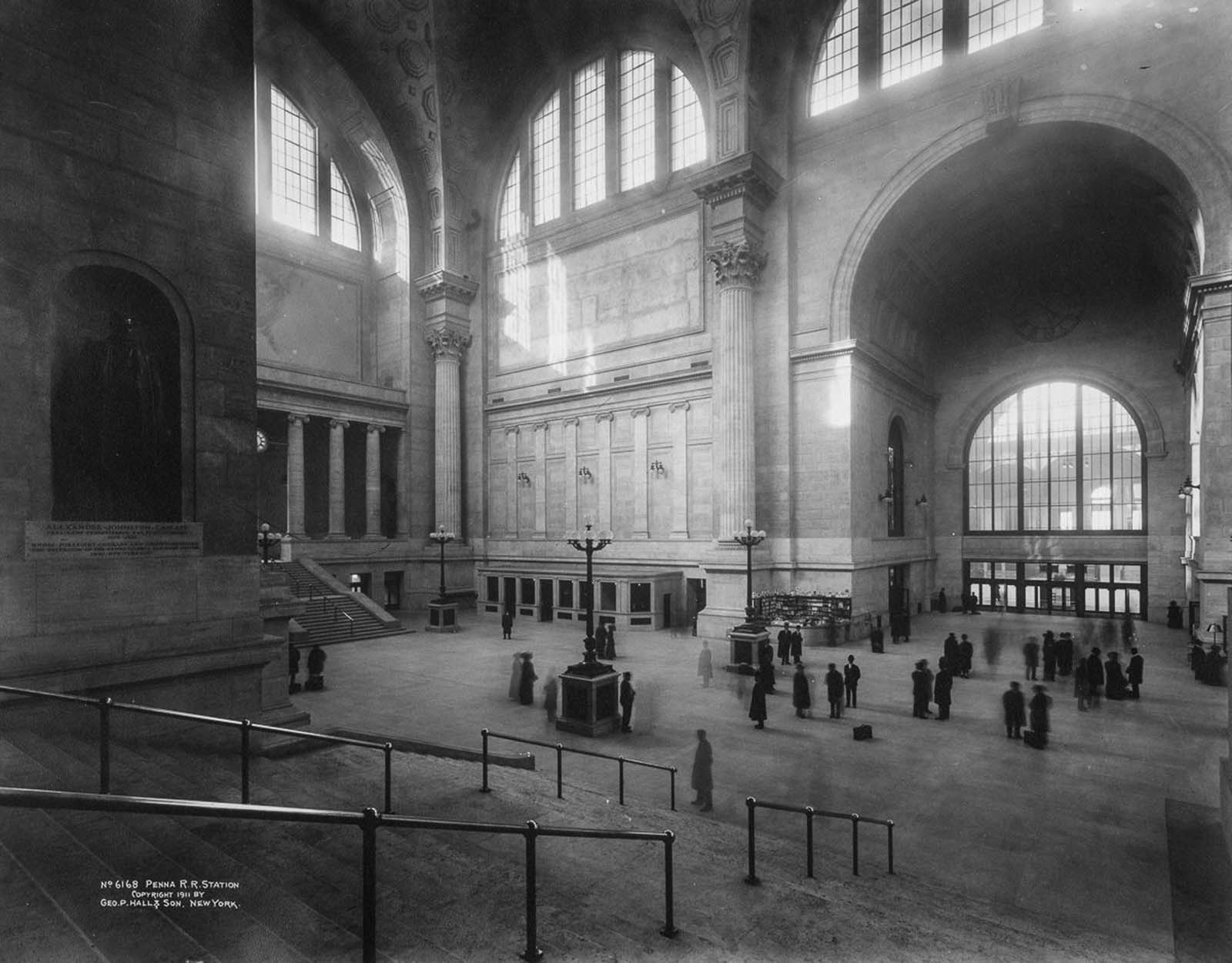

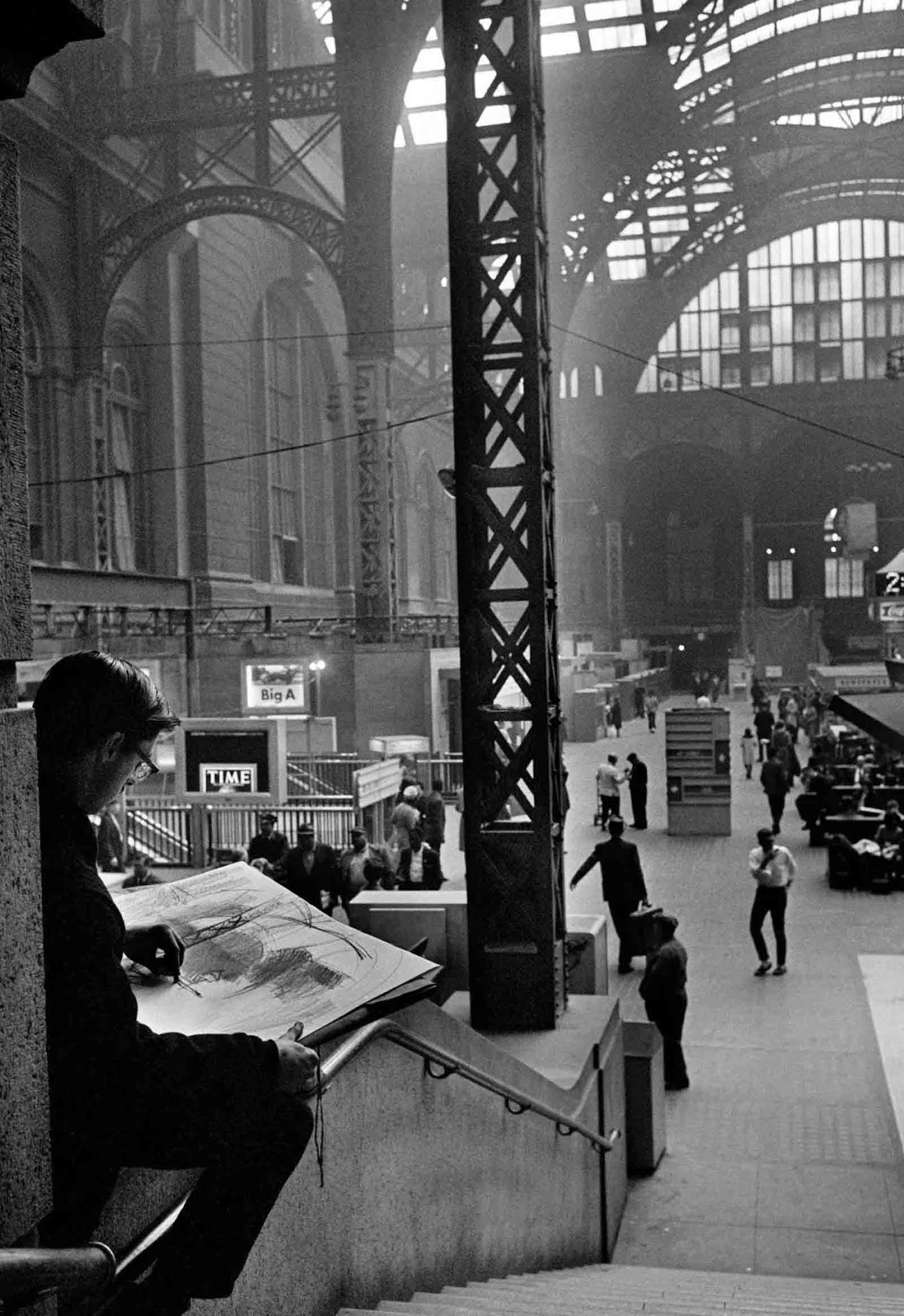

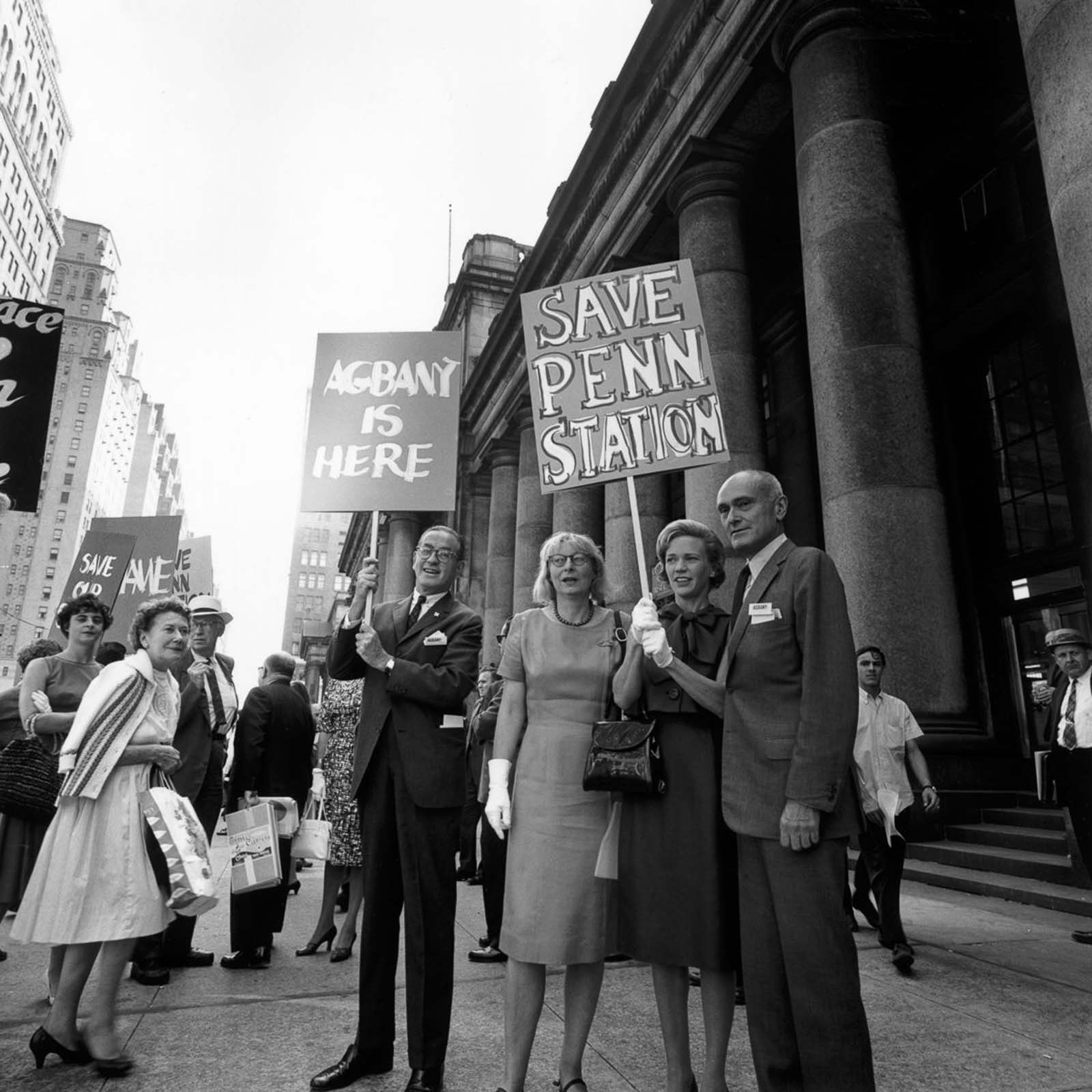

From construction to destruction, we visit the station’s crowded, light-filled concourse, its ornate statues, and its dedicated people. Although this impressive building only stood from 1910 to 1963, the memory of its majestic presence in the heart of New York City lives on to this day. The story begins in the late 1890s when Pennsylvania Railroad leaders Alexander Cassatt and Samuel Rea dared to pioneer two feasts. First, they would lay down tracks in the turbulent Hudson and East Rivers to reach Manhattan, which had become a global hub of commerce. They were visionaries, as tunneling was a concept few had heard off. Second, they would build a monumental station in the heart of one of New York’s most notorious, corrupt and vice-filled neighborhoods. It would be a station that would do more than transport passengers. It would ennoble the public. For the passerby, whether rich or poor, it was as if Rome had been brought to his backyard. It was a station that would inspire the world, even if only for half a century. Inspired by the Gare du Quai d’Orsay in Paris and Baths of Caracalla in Rome, the planners of Penn Station sought to uplift the society. Grandiose architecture transformed a point of destination to a place of wonder. Occupying two city blocks from Seventh Avenue to Eighth Avenue and from 31st to 33rd Streets in Midtown Manhattan, the original Penn Station building was designed by McKim, Mead & White and completed in 1910. The station enabled direct rail access to New York City from the south for the first time. Covering an area of about 8 acres (3.2 ha), it had frontages of 788 feet (240 m) along the side streets and 432 feet (132 m) long along the main avenues. The land lot occupied about 800 feet (240 m) along 31st and 33rd Streets. Its head house and train shed were considered a masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style and one of the great architectural works of New York City. The station contained 11 platforms serving 21 tracks, in approximately the same layout as the current Penn Station. The original building was one of the first stations to include separate waiting rooms for arriving and departing passengers, and when built, these were among the city’s largest public spaces. The original structure was made of 14,000 m3 of pink granite, 1,700 m3 of interior stone, 27,000 short tons of steel, 48,000 short tons of brick, and 30,000 light bulbs. The building had an average height of 69 feet (21 m) above the street, though its maximum height was 153 feet (47 m). Some 25 acres (10 ha) of track surrounded Penn Station. At the time of Penn Station’s completion, The New York Times called it “the largest building in the world ever built at one time”. Classical Greek-style Doric order. These columns, in turn, were modeled after landmarks such as the Acropolis of Athens. The rest of the facade was modeled on St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City, as well as the Bank of England headquarters. The main waiting room was inspired by Roman structures such as the Baths of Caracalla, Diocletan, and Titus. The room measured 314 feet 4 inches (95.81 m) long, 108 feet 8 inches (33.12 m) wide, and 150 feet (46 m) tall. Additional waiting rooms for men and women, each measuring 100 by 58 feet (30 by 18 m), were on either side of the main waiting room. The room approximated the scale of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The lower walls were of travertine, while the upper walls were expressed in a steel framework clad in plaster, decorated to resemble the lower walls. The travertine was sourced from Campagna in Italy. The ceiling was supported by Corinthian columns on pedestals, measuring 59.5 feet (18.1 m) tall from the tops of the pedestals to the tops of the capitals. There were three semicircular windows on top of the waiting room’s walls; each had a radius of 38 feet 4 inches (11.68 m). The artist Jules Guérin was commissioned to create six murals for Penn Station’s waiting room; each of his works were over 100 feet (30 m) tall. At the station’s completion, the total project cost to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (equivalent to $2.5 billion in 2021), according to an Interstate Commerce Commission report. When Penn Station opened, it had a capacity of 144 trains per hour on its 21 tracks and 11 platforms. At the start of operations, there were 1,000 trains scheduled every weekday. Penn Station had started to decline in the 1930s. The station was busiest during World War II: in 1945, more than 100 million passengers traveled through Penn Station. The station’s decline came soon afterward with the beginning of the Jet Age and the construction of the Interstate Highway System. The PRR recorded its first-ever annual operating losses in 1947, and intercity rail passenger volumes continued to decline dramatically over the next decade. By the 1950s, its ornate pink granite exterior had become coated with grime. A renovation in the late 1950s covered some of the grand columns with plastic and blocked off the spacious central hallway with the “Clamshell”, a new ticket office designed by Lester C. Tichy. Architectural critic Lewis Mumford wrote in The New Yorker in 1958 that “nothing further that could be done to the station could damage it”. In 1962 plans were revealed to demolish the terminal and build an entertainment venue Madison Square Garden on top of it. The new train station would be entirely underground and boast amenities such as air-conditioning and fluorescent lighting. At the time, one argument made in favor of the old Penn Station’s demolition was that the cost of maintaining the structure had become prohibitive. Its grand scale made the PRR devote a “fortune” to its upkeep, and the head house’s exterior had become somewhat grimy. Those who opposed demolition considered whether it made sense to preserve a building, intended to be a cost-effective and functional piece of the city’s infrastructure, simply as a monument to the past. As a New York Times editorial critical of the demolition noted at the time, “any city gets what it wants, is willing to pay for, and ultimately deserves.” The architectural community, in general, was surprised by the announcement of the head house’s demolition. Modern architects rushed to save the ornate building, although it was contrary to their own styles. They called the station a treasure and chanted “Don’t Amputate – Renovate” at rallies. Despite large public opposition to Penn Station’s demolition, the New York City Department of City Planning voted in January 1963 to start demolishing the station that summer. The destruction of Penn Station was a tragedy for New York City and the world. A monument built “for the ages” lasted only fifty-two years, to be replaced by a mundane underground station, cramped and dark, with an entertainment complex on top. Penn Station became the martyr, as its destruction led to the Landmarks Commission and subsequent savings of other historical buildings like Grand Central Station. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger summarized the station’s fate: “Penn Station represented the aspiration of doing something monumental and noble, of private enterprise creating something extraordinary for the benefit of the public. It was an investment from which future generations would benefit from. The challenge is how you balance the need to preserve what’s best, what’s most important, and the need to invent continually, and change and grow, because that’s what living places have to do”. The replacement Penn Station was built underneath Madison Square Garden at 33rd Street and Two Penn Plaza. The station spans three levels, with the concourses on the upper two levels and the train platforms on the lowest level. The two levels of concourses, while original to the 1910 station, were renovated extensively during the construction of Madison Square Garden and expanded in subsequent decades. The general reception of the replacement station has been largely negative. Comparing the new and old stations, Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully once wrote, “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.”

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Museum of the City of New York / The New York Historical Society / The New York Times / Wikimedia Commons / Article based on New York’s Original Penn Station: The Rise and Tragic Fall of an American Landmark). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe