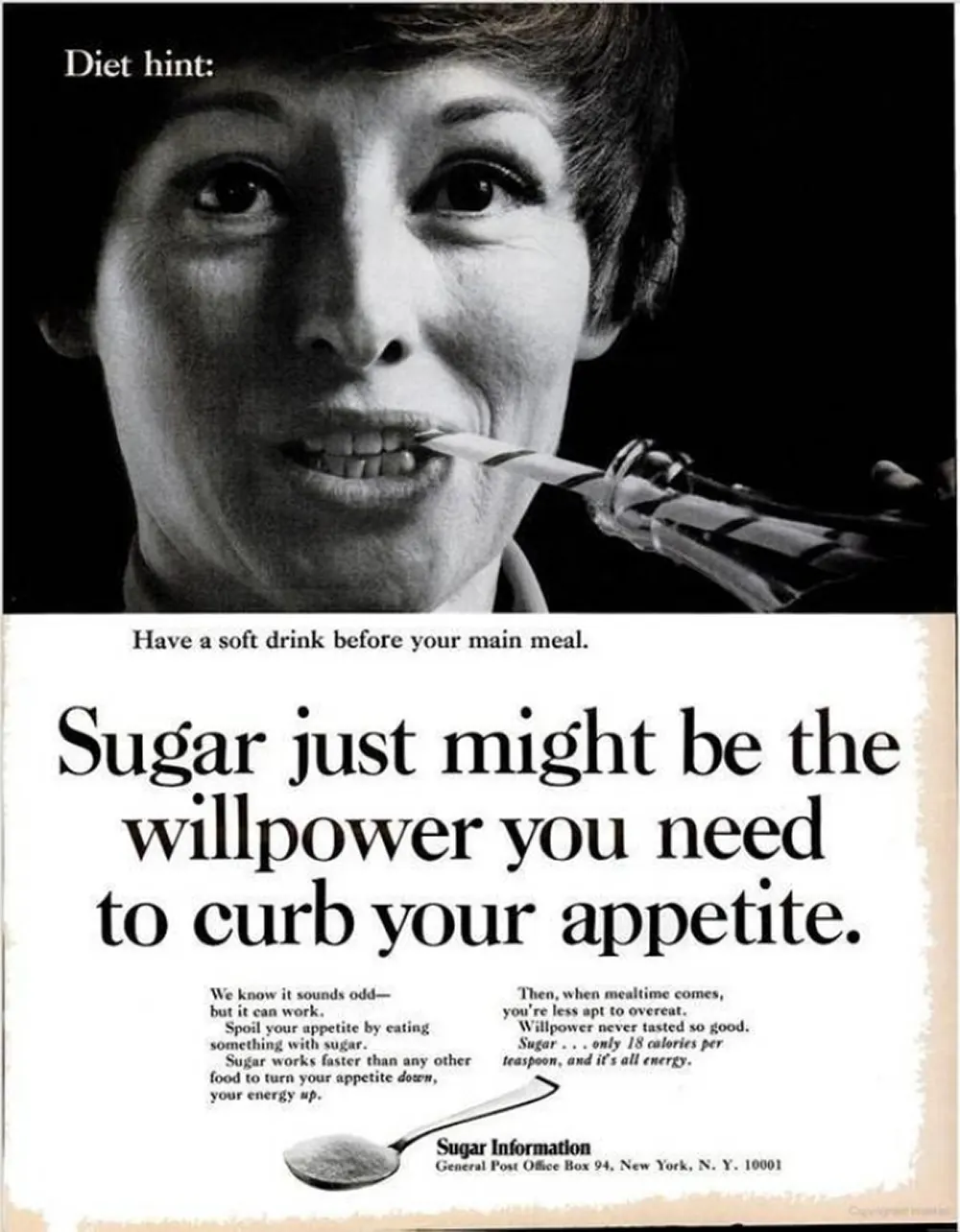

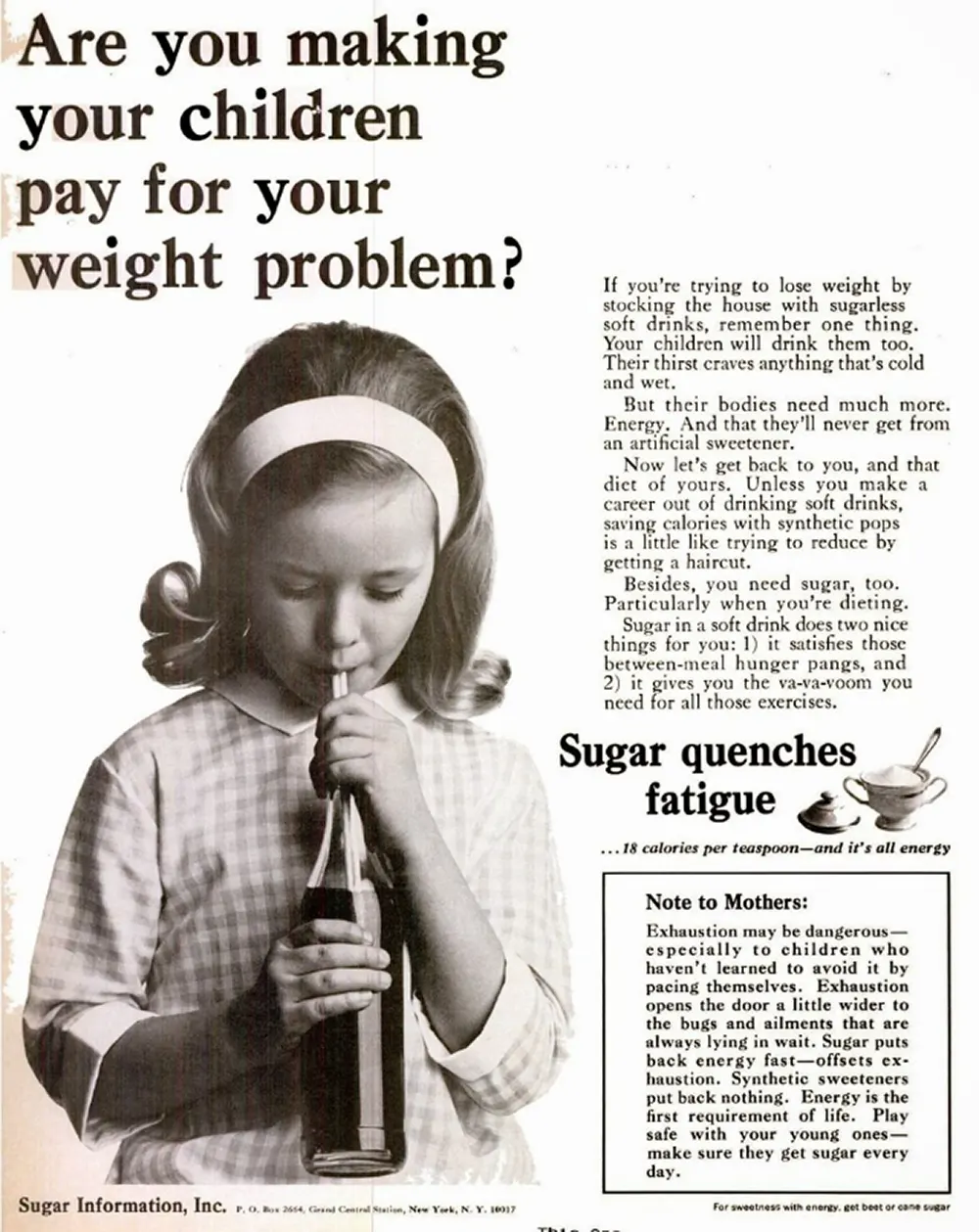

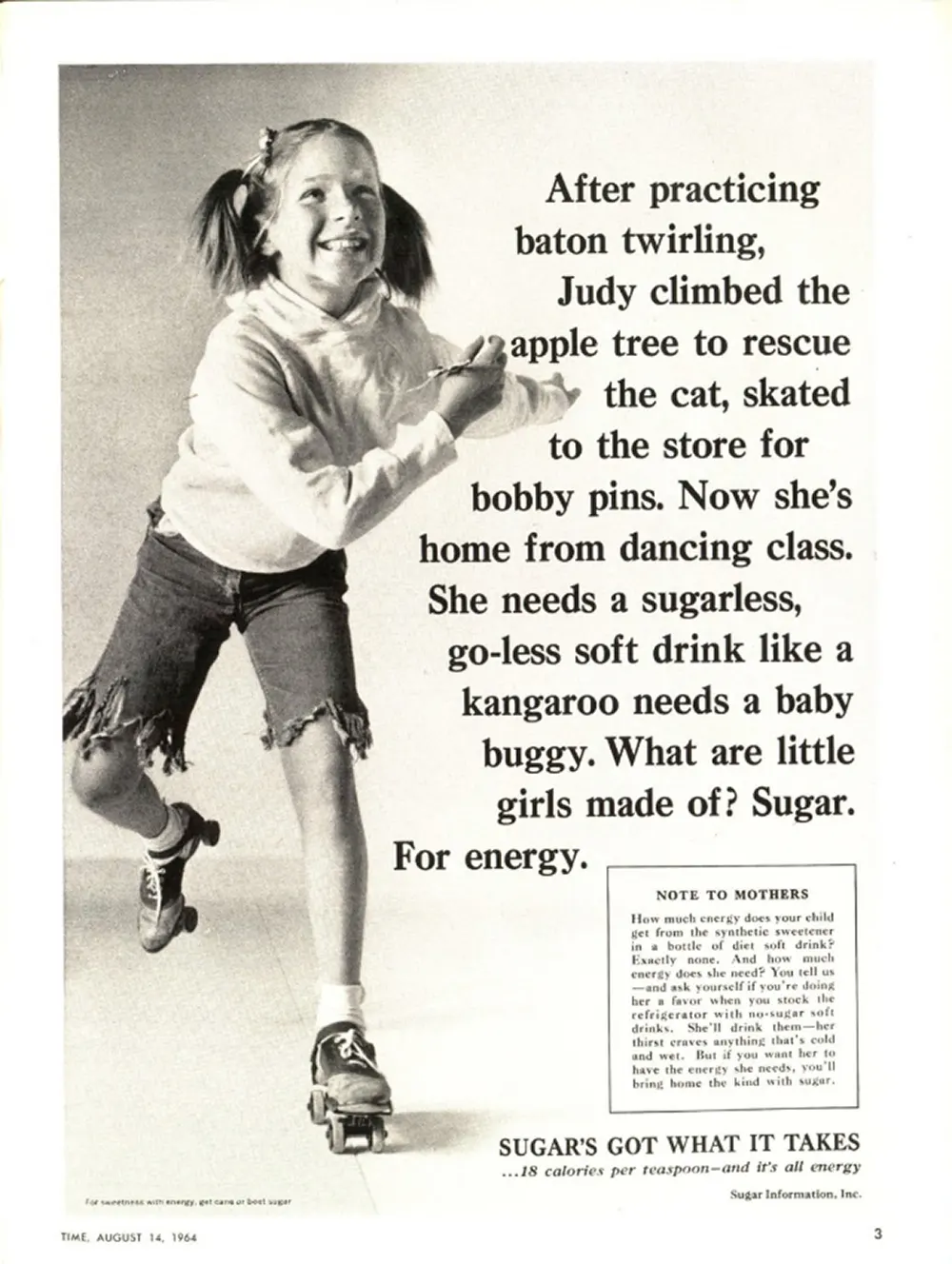

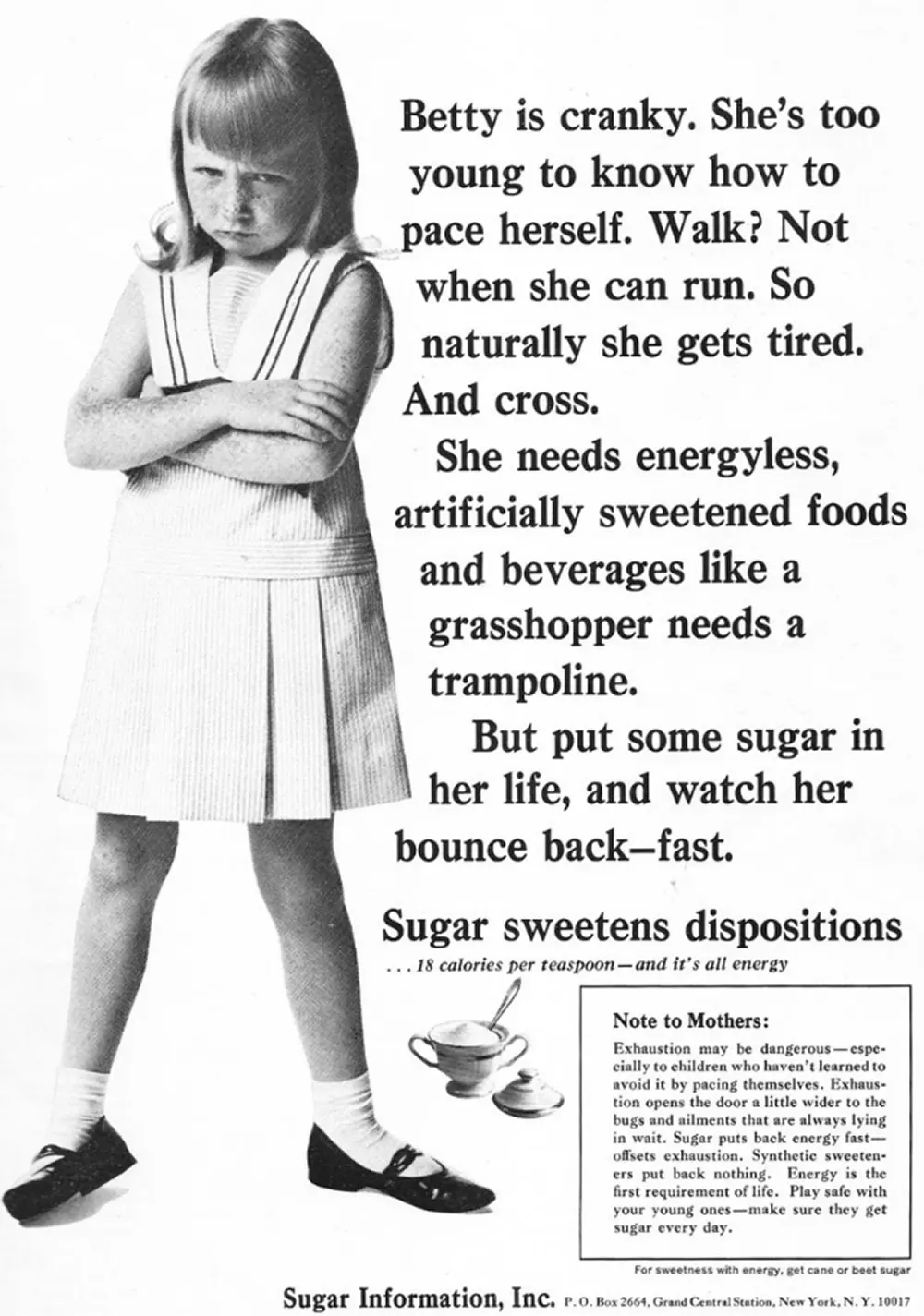

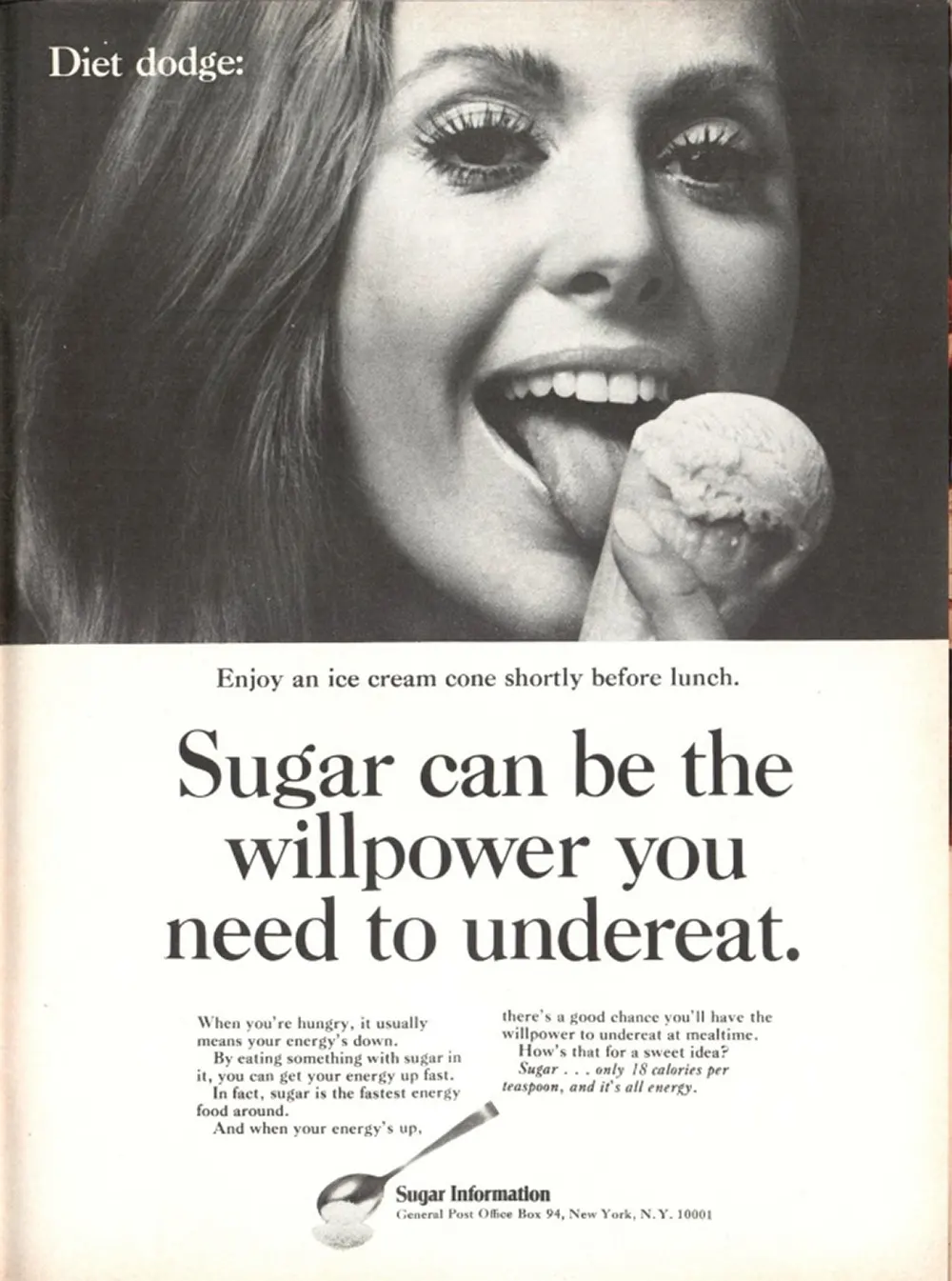

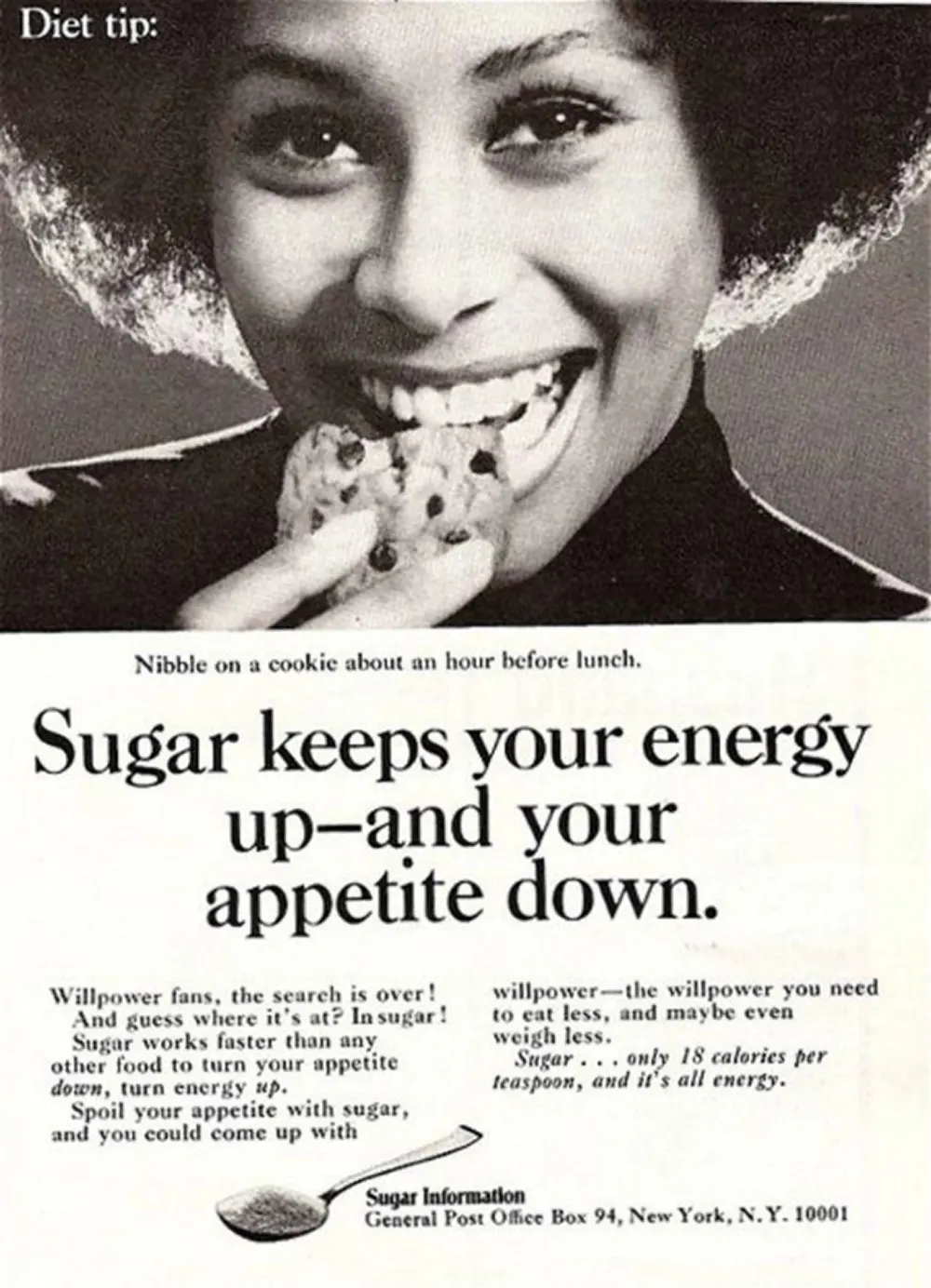

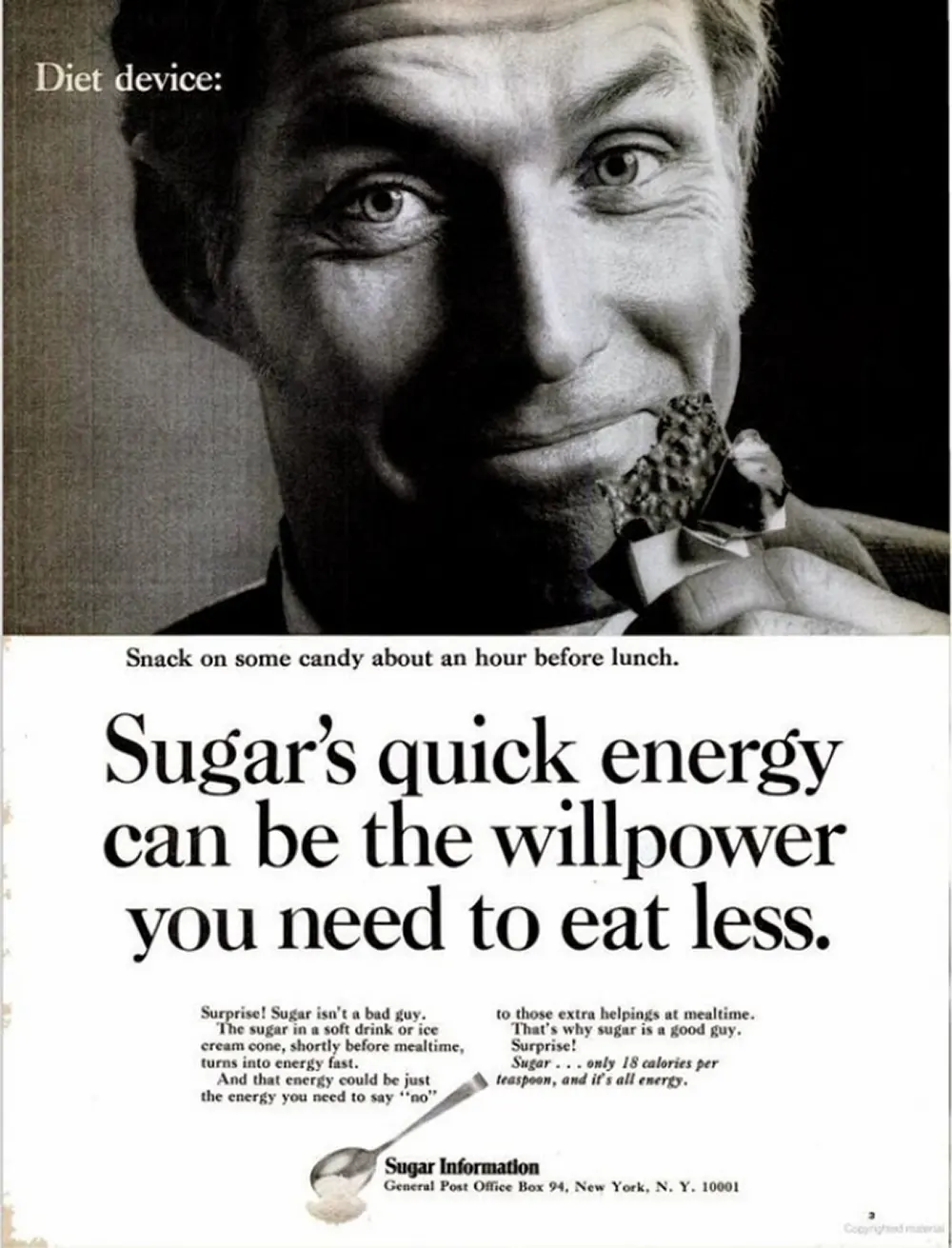

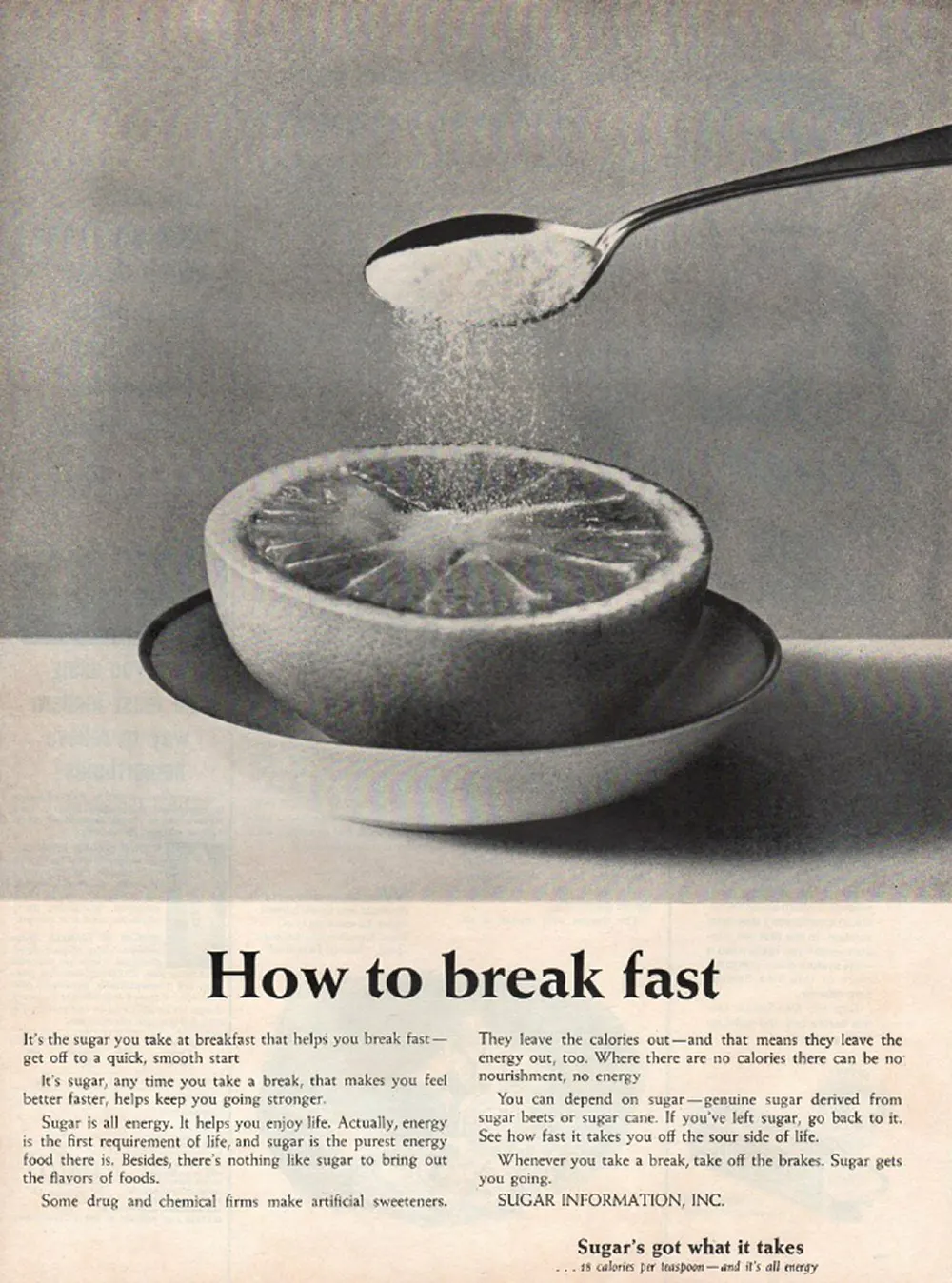

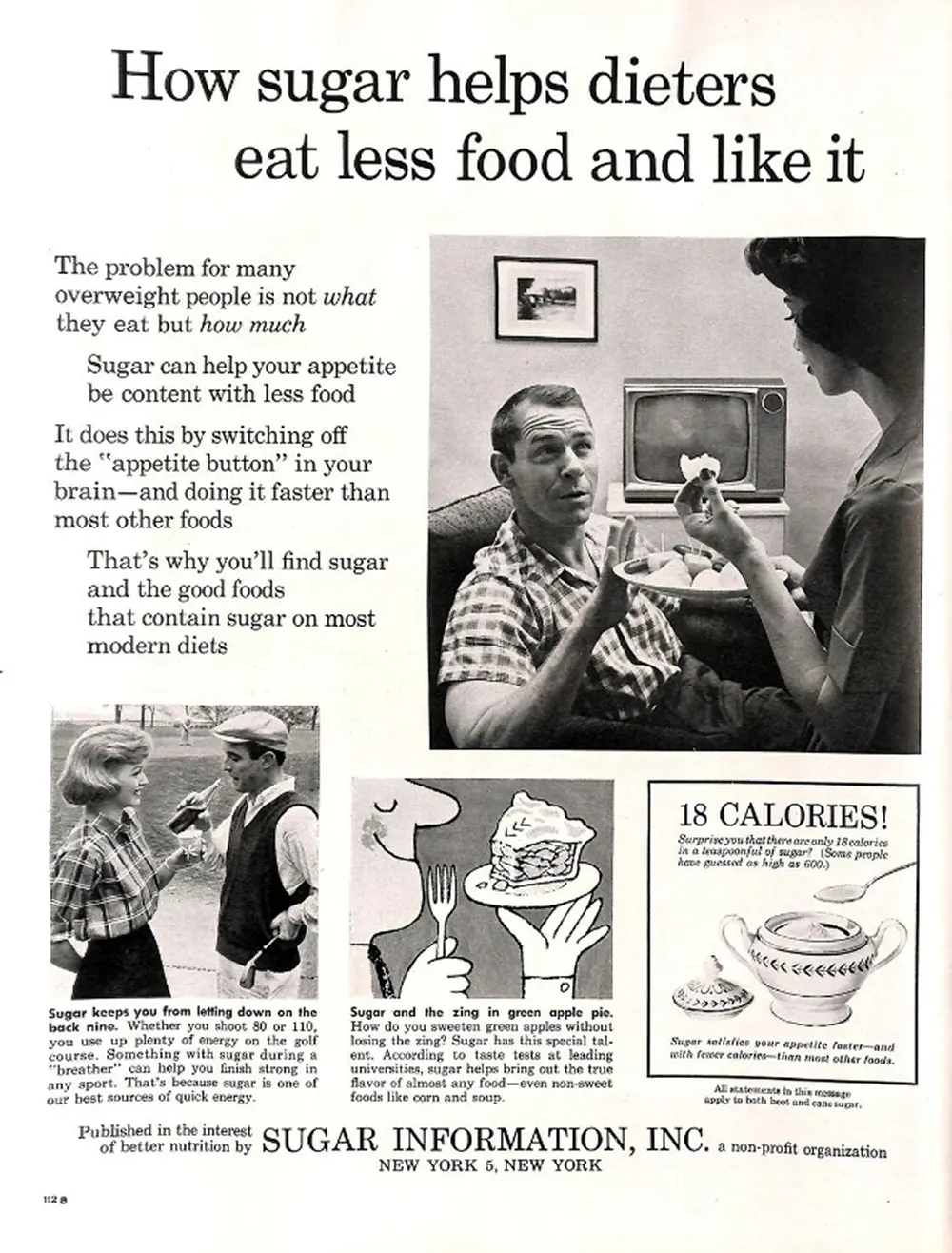

A “pro-sugar” ad that appeared in an August 1964 issue of Time gave a “note to mothers,” explaining that drinks without sugar wouldn’t provide children with the necessary energy to get through the day’s activities. This form of advertisement began in the 1950s when health researchers were spreading the news that sugar was connected to weight gain. As a response to this “negative” news, the sugar industry upped its advertising budget. In 1955, Sugar Association even won an award for “advertising in the public interest.” Diet sodas became popular in the mid-1960s, and the sugar industry countered ads for diet drinks, stating that the beverages would not help customers lose weight, because synthetic sugar was not energizing and satisfying the way that “full sugar” is. The pro-sugar advertising campaign was, in large part, based on a health concept called “appestat” which was defined by a nutritionist in New York City for a weight loss book in 1952. The concept explained that an “individual’s appetite-regulating mechanism” could leave him/her unsatisfied after meals, making the person more likely to overeat. Sugar was believed to be able to “turn down” the appestat while providing the body with energy. Methods of marketing sugary products included: using words associated with health, such as “healthy”, “natural”, “naturally sweetened” and “lightly sweetened”; using associations with fruit to imply healthiness; positioning sugary drinks and foods as a freedom-of-choice issue rather than a public health one. Other tricks included shill advertising, through front groups and individuals with no obvious connection to the sugar industry, including people presenting themselves as independent scientists By the end of 1971, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) put a stop to these sugar advertisements, citing that even though the ads suggested that eating real sugar meant consuming fewer calories, that wasn’t accurate information. This is also during the time that the FTC started asking advertisers to supply proof for their claims. It is thought that cane sugar was first used by man in Polynesia from where it spread to India. In 510 BC the Emperor Darius of what was then Persia invaded India where he found “the reed which gives honey without bees”. The secret of cane sugar, as with many other of man’s discoveries, was kept a closely guarded secret whilst the finished product was exported for a rich profit. It was the major expansion of the Arab peoples in the seventh century AD that led to a breaking of the secret. When they invaded Persia in 642 AD they found sugar cane being grown and learnt how sugar was made. As their expansion continued they established sugar production in other lands that they conquered including North Africa and Spain. Sugar was only discovered by western Europeans as a result of the Crusades in the 11th Century AD. Crusaders returning home talked of this “new spice” and how pleasant it was. The first sugar was recorded in England in 1099. The subsequent centuries saw a major expansion of western European trade with the East, including the importation of sugar. It is recorded, for instance, that sugar was available in London at “two shillings a pound” in 1319 AD. This equates to about US$100 per kilo at today’s prices so it was very much a luxury. In the 15th century AD, European sugar was refined in Venice, confirming that even then when quantities were small, it was difficult to transport sugar as a food-grade product. In the same century, Columbus sailed to the Americas, the “New World”. It is recorded that in 1493 he took sugar cane plants to grow in the Caribbean. The climate there was so advantageous for the growth of the cane that an industry was quickly established. Contemporaries often compared the worth of sugar with valuable commodities including musk, pearls, and spices. Sugar prices declined slowly as its production became multi-sourced throughout the European colonies. Once an indulgence only of the rich, the consumption of sugar also became increasingly common among the poor as well. During the 18th century, sugar became enormously popular. Great Britain, for example, consumed five times as much sugar in 1770 as in 1710. By 1750, sugar surpassed grain as “the most valuable commodity in European trade — it made up a fifth of all European imports and in the last decades of the century four-fifths of the sugar came from the British and French colonies in the West Indies.” From the 1740s until the 1820s, sugar was Britain’s most valuable import. The sugar market went through a series of booms. The heightened demand and production of sugar came about to a large extent due to a great change in the eating habits of many Europeans. For example, they began consuming jams, candy, tea, coffee, cocoa, processed foods, and other sweet victuals in much greater amounts. Reacting to this increasing trend, the Caribbean islands took advantage of the situation and set about producing still more sugar. In fact, they produced up to ninety percent of the sugar that the western Europeans consumed. Some islands proved more successful than others when it came to producing the product. In Barbados and the British Leeward Islands, sugar provided 93% and 97% respectively of exports. As Europeans established sugar plantations on the larger Caribbean islands, prices fell in Europe. By the 18th century, all levels of society had become common consumers of the former luxury product. At first, most sugar in Britain went into tea, but later confectionery and chocolates became extremely popular. Many Britons (especially children) also ate jams. Suppliers commonly sold sugar in the form of a sugarloaf and consumers required sugar nips, a pliers-like tool, to break off pieces. Beginning in the late 18th century, the production of sugar became increasingly mechanized. The steam engine first powered a sugar mill in Jamaica in 1768, and soon after, steam replaced direct firing as the source of process heat. In 1813 the British chemist Edward Charles Howard invented a method of refining sugar that involved boiling the cane juice not in an open kettle, but in a closed vessel heated by steam and held under partial vacuum. At reduced pressure, water boils at a lower temperature, and this development both saved fuel and reduced the amount of sugar lost through caramelization. Further gains in fuel efficiency came from the multiple-effect evaporator, designed by the United States engineer Norbert Rillieux (perhaps as early as the 1820s, although the first working model dates from 1845). This system consisted of a series of vacuum pans, each held at a lower pressure than the previous one. The vapors from each pan served to heat the next, with minimal heat wasted.

(Photo credit: The Atlantic / atlantablackstar.com / Wikimedia Commons / Time Magazine / Pinterest). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe