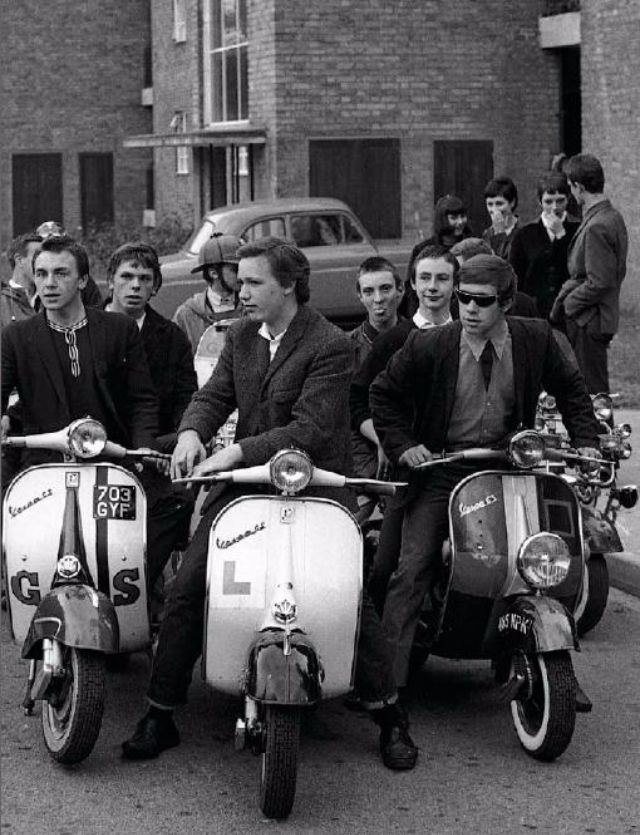

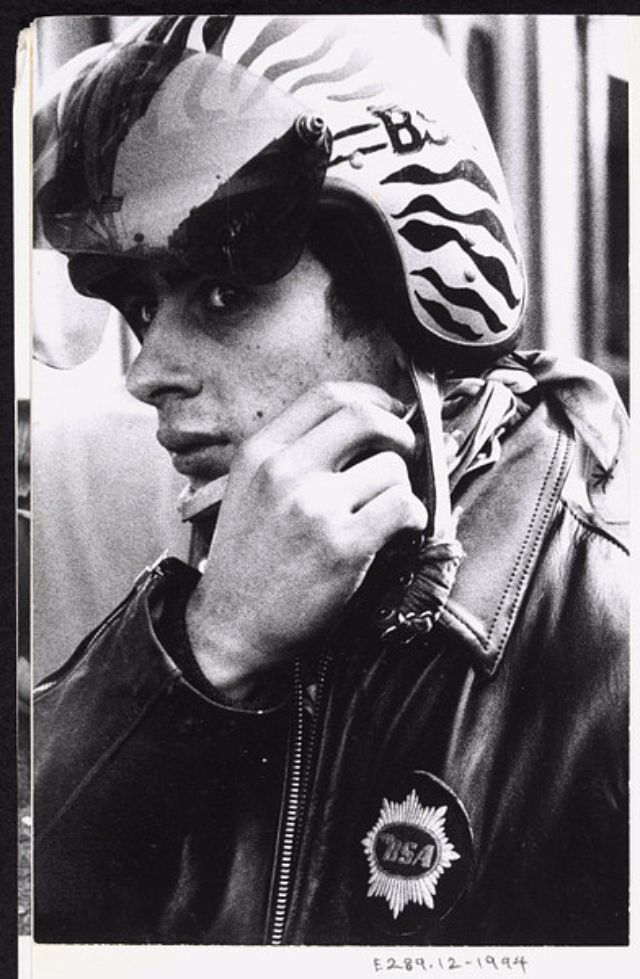

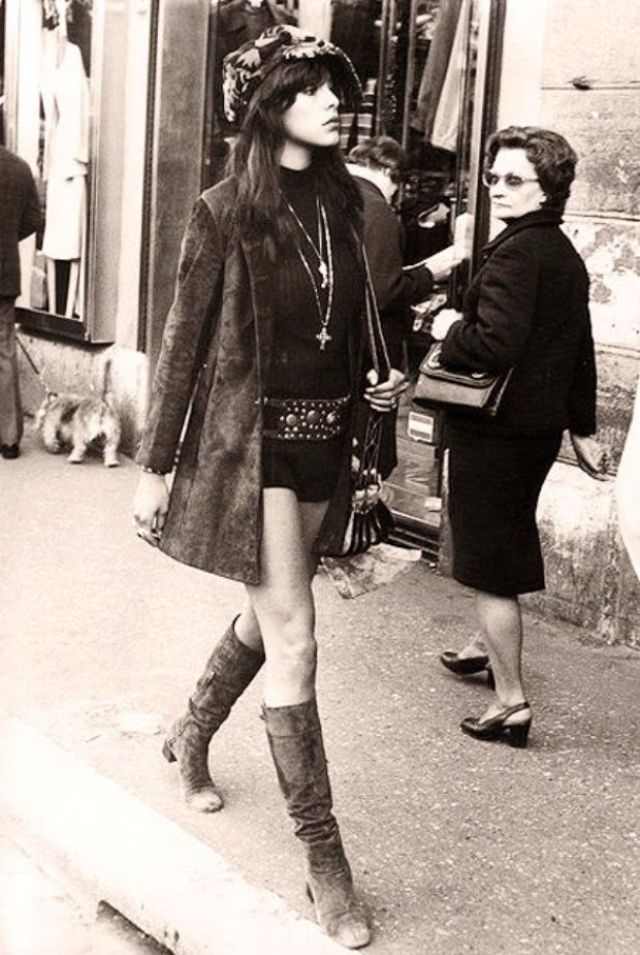

The baby boomers were coming of age, and they were unlike any generation before them – adventurous, rebellious, and eager to carve out their own identities. This era saw the rise of two iconic youth groups: the mods and the rockers. It was a clash of cultures, leather-clad rockers facing off against the stylish mods. Media coverage of the two groups fighting in 1964 sparked a moral panic about British youth, and they became widely perceived as violent, unruly troublemakers. The rocker subculture was all about motorcycles, with members decked out in gear like black leather jackets and motorcycle boots or brothel creepers. This style took cues from Marlon Brando’s iconic look in the 1953 film “The Wild One.” Rockers typically sported a pompadour hairstyle and grooved to 1950s rock and roll and R&B tunes, favoring artists like Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, and Bo Diddley, as well as British rock and roll stars such as Billy Fury and Johnny Kidd. On the other hand, the mod subculture focused on fashion and music, with many mods opting to ride scooters. Mods were known for their sharp attire, often wearing suits and other neat outfits. They listened to a variety of music genres, including modern jazz, soul, Motown, ska, and British blues-rooted bands like the Yardbirds, the Small Faces, and the Who. Fueled by hormones, rebellion, and the sounds of rock music, mods and rockers often found themselves in fights that, whether justified or not, had a significant impact on England. These encounters were typically small-scale, with individuals from different backgrounds letting their disagreements turn physical in the midst of busy streets. In May 1964, BBC News reported that mods and rockers had been imprisoned following riots in seaside resort towns in Southern England, including Margate in Kent, Brighton in Sussex, and Clacton in Essex. The conflicts first erupted in Clacton and Hastings over the Easter weekend of 1964. A second wave of clashes occurred during the Whitsun weekend (18 and 19 May 1964) along the south coast of England, particularly in Brighton. Here, fights spanned two days and spilled over to Hastings. A group of rockers found themselves cornered on Brighton beach, where they were outnumbered and attacked by mods, despite police protection. Order was eventually restored, and a judge imposed substantial fines, referring to those arrested as “sawdust Caesars.” The clashes between mods and rockers were widely depicted in newspapers as having reached “disastrous proportions,” with both groups being labeled as “vermin” and “louts.” Newspaper editorials further fueled the hysteria, such as a May 1964 editorial in the Birmingham Post, which cautioned that mods and rockers were “internal enemies” capable of “bringing about disintegration of a nation’s character.” The magazine Police Review argued that the mods and rockers’ perceived disregard for law and order could lead to violence spreading “like a forest fire.” Stanley Cohen, a renowned sociologist, coined the term “moral panic” after his in-depth study of the mods and rockers conflict. His groundbreaking work, “Folk Devils and Moral Panics,” published in 1972, scrutinized how the media portrayed the clashes between mods and rockers in the 1960s. While acknowledging that these groups did engage in some fights during the mid-1960s, Cohen argued that these altercations were no more serious than the typical scuffles that occurred among youth in seaside resorts and after football games in the preceding decade. Cohen’s analysis shed light on how the UK media transformed the mod subculture into a symbol of delinquency and deviance. He pointed out that as media coverage sensationalized the image of knife-wielding mods, it created a perception that anyone wearing a fur-collared anorak and riding a scooter was a potential threat, leading to hostile and punitive reactions. Moreover, Cohen criticized the media for sensationalizing the issue further by possibly fabricating interviews with supposed rockers, like the infamous “Mick the Wild One.” The media also exploited unrelated accidents, such as the accidental drowning of a youth, to fuel the narrative, exemplified by headlines like “Mod Dead in Sea.”

(Photo credit: Pinterest / Wikimedia Commons / Flickr). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe

.jpg)

.jpg)