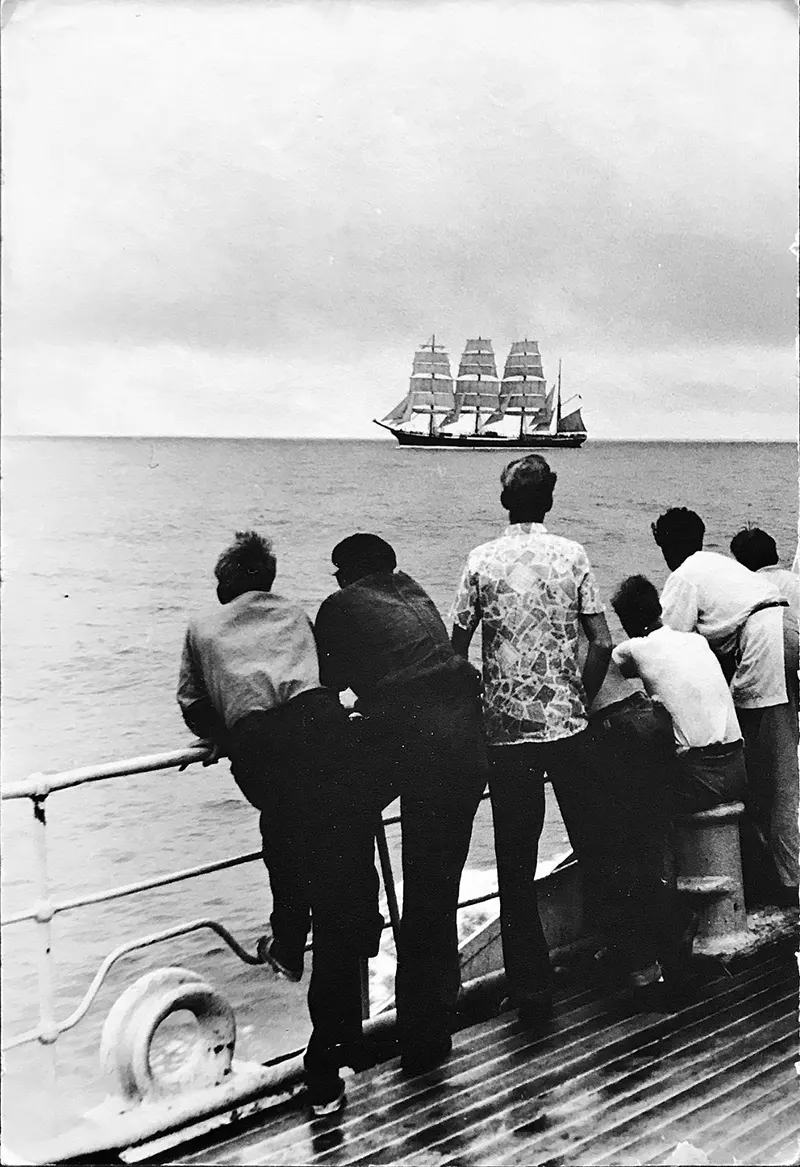

This remarkable vessel, whose construction was a marvel of its time, bears witness to an important moment in maritime history. In 1949, she was the last commercial sailing ship to round Cape Horn. Pamir was built at the Blohm & Voss shipyards in Hamburg and launched on 29 July 1905. She had a steel hull and tonnage of 3,020 GRT (2,777 net). She had an overall length of 114.5 m (375 ft), a beam of about 14 m (46 ft) and a draught of 7.25 m (23.5 ft). Three masts stood 51.2 m (168 ft) above deck and the main yard was 28 m (92 ft) wide. She carried 3,800 m² (40,900 ft²) of sails and could reach a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h). However, her regular cruise speed was around 8-9 knots. By 1914, she had made eight voyages to Chile, taking between 64 and about 70 days for a one-way trip from Hamburg to Valparaíso, the foremost Chilean nitrate ports at the time. From October 1914, she stayed in Santa Cruz de la Palma port in La Palma Island, Canary Islands. In 1920, she was handed over to Italy as war reparation. On 15 July 1920, she left Hamburg via Rotterdam to Naples towed by tugs. The Italian government was unable to find a deep-water sailing ship crew, and a few years later the F. Laeisz Company bought her back. In 1924, the F. Laeisz Company bought her back for £7,000 and put her into service in the nitrate trade again. Laeisz sold her in 1931 to the Finnish shipping company of Gustaf Erikson, which used her in the Australian wheat trade. During World War II, Pamir was seized as a prize of war by the New Zealand government on 3 August 1941 while in port at Wellington. Ten commercial voyages were made under the New Zealand flag: five to San Francisco, three to Vancouver, one to Sydney and her last voyage across the Tasman from Sydney to Wellington carrying 2,700 tons of cement and 400 tons of nail wire. The war’s end marked a turning point. The age of sail was waning as steam and motor vessels took center stage in global shipping. The Pamir, once a symbol of maritime grandeur, found itself increasingly outmoded in the face of modern technology. In a 128-day journey to Falmouth, the Pamir made history on July 11, 1949. She became the final windjammer to navigate Cape Horn while carrying valuable cargo, a testament to her seaworthiness and the legacy of sail-powered ships. Tragically, the Pamir’s final chapter unfolded in the unforgiving waters of the Atlantic Ocean. In September 1957, while en route from Buenos Aires to Hamburg with a cargo of grain, the ship encountered a ferocious storm. The combination of heavy seas and high winds proved too much for the aging vessel. On September 21, 1957, the Pamir succumbed to the elements, sinking beneath the waves. The tragedy of the Pamir’s sinking extended beyond the loss of a ship. Only six of the 86 crew members survived, making it one of the deadliest shipwrecks of its time. The sinking marked the end of an era, closing the book on the commercial sailing ships that had once dominated the world’s oceans. The survivors reported that crew and cadets stayed very calm until close to the loss of the ship because the ship was not believed to be in difficulties – some sailors were still taking photographs, and supposedly some complained when ordered to put on life jackets. Even at the very end, there was no panic. She was not going head into the wind at any time, and her engine was not used. At least one lifeboat broke free before the capsize; others detached briefly before or during the capsizing and sinking. Nobody boarded a lifeboat before she capsized, and nobody jumped overboard: when she capsized, all 86 men were still on board. Her masts did not break nor did any yards or anything else fall down, so nothing was dragging to the side. Some sails were left until they were blown out, but others were shortened or cut off by the crew; the headsail had to be cut with knives before it would blow out. When she sank, she still had set about a third of the mizzen sail and some tarpaulin in the shrouds of the mizzen mast. Pamir’s last voyage was the only one in her school ship career during which she made a profit, as the insurance sum of about 2.2 million Deutsche Mark was sufficient to cover the company losses for that year. While there was no indication that this was the intention of the consortium, which was never legally blamed for the sinking, some later researchers have considered that through its neglect it was at least strongly implicated in the loss. The legacy of the Pamir lives on through photographs, historical accounts, and the collective memory of those who appreciate the romance and significance of the age of sail. The Pamir’s story is a reminder of an epoch when the oceans were navigated by majestic vessels driven by the age-old power of the wind.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr / Pinterest). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe