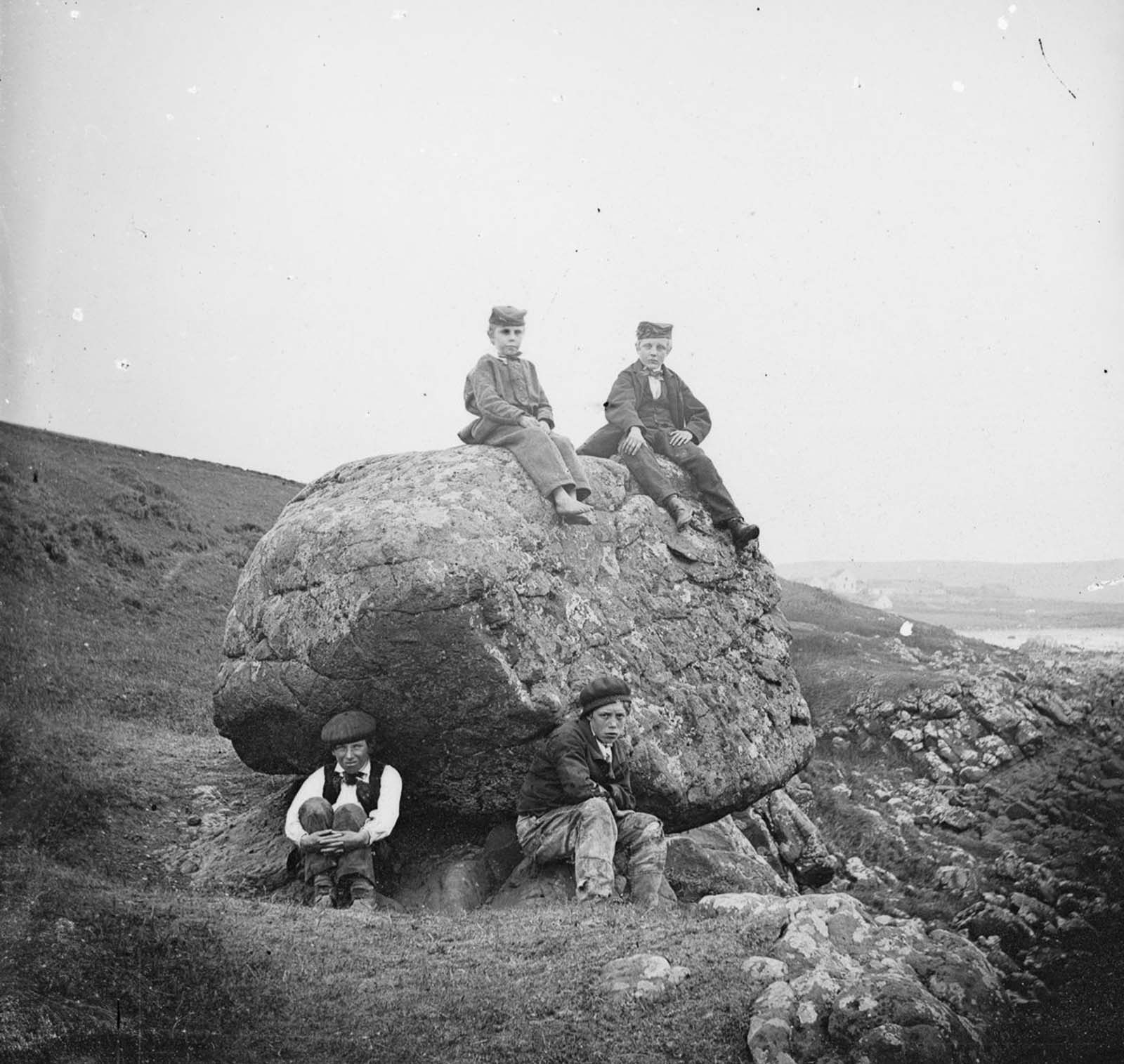

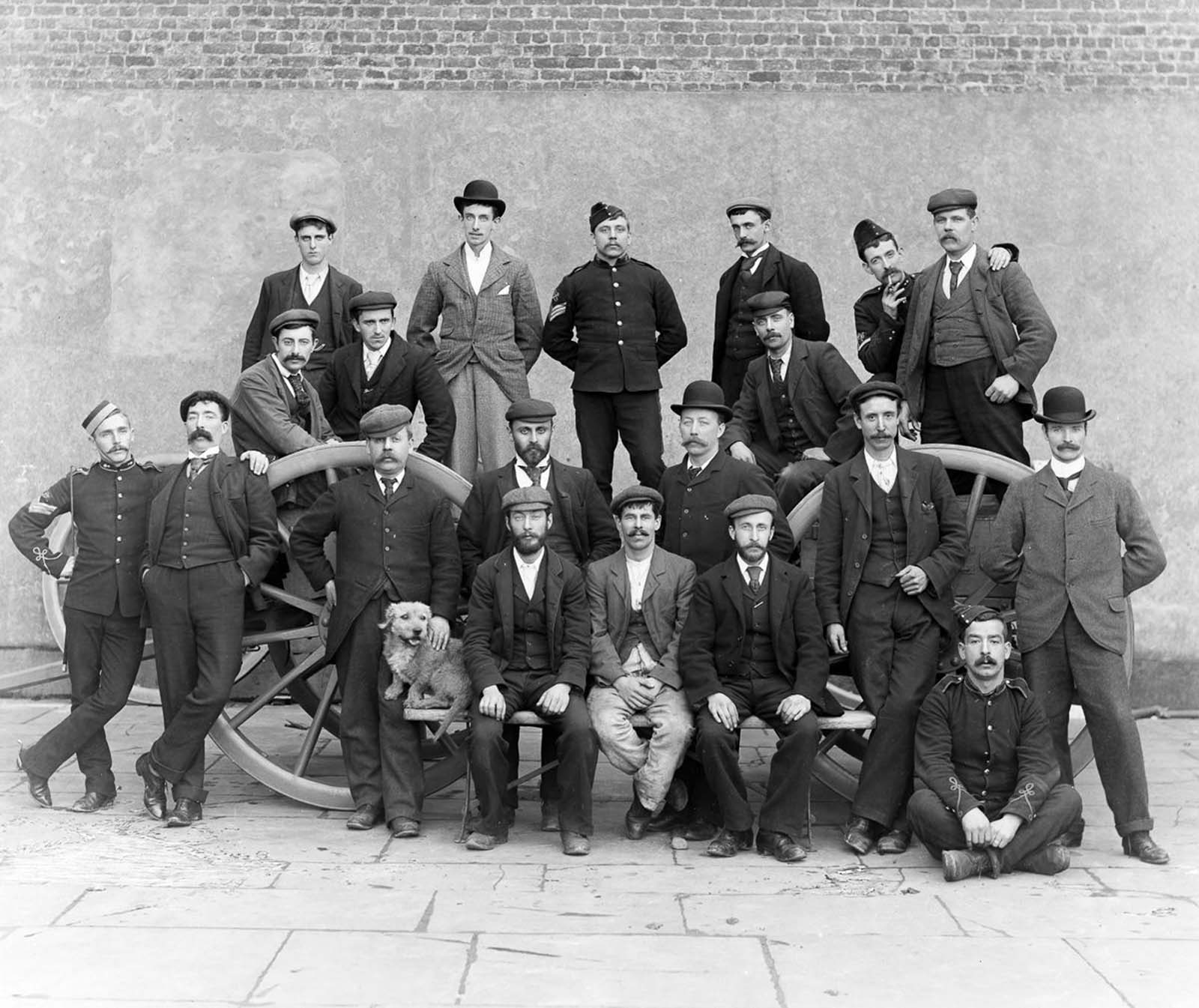

Ireland’s population had plummeted by more than three and a half million since the Famine and was still in decline. There were some 250,000 fewer people on the island in 1901 than there had been in 1891. Late-nineteenth century Ireland was a country of tiny farmsteads and nasty urban tenements. It was an era when some Irish people still lived in mud cabins. Partial failure of the potato crop, which happened a number of times during the 1890s, was still capable of generating what late-Victorian administrators coyly called ‘distress’. This was a time before the introduction of old age pensions and social welfare arrangements when the workhouse, however harsh its conditions might be, was often the only place of refuge for the aged, the infirm and the indigent. To many, emigration offered the only prospect of a better life. More than 32,000 people left in 1899 alone, giving Ireland a higher emigration rate than any other part of Europe. There were thousands of others who migrated for part of the year in search of seasonal labor whose proceeds could help sustain their families at home. Infant death was still commonplace. Almost one in every four children born in Dublin died before their first birthday. In Belfast, during one four-week period in 1900, there were as many deaths of children less than one year old as there were of adults over sixty years of age. At a time when medicine was far less advanced than it is today, one-third of all deaths resulted from chest infections. Although average life expectancy had climbed significantly from its pre-Famine level of under forty years, at the turn of the century a normal life span was still some twenty years shorter than it is today. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, militant and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of World War I. By 1918, however, moderate Irish nationalism had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. In 1919, war broke out between republican separatists and British Government forces. Subsequent negotiations between Sinn Féin, the major Irish party, and the UK government led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which resulted in five-sixths of Ireland seceding from the United Kingdom. (Photo credit: National Library of Ireland / Daniel Mulhall History Ireland). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe