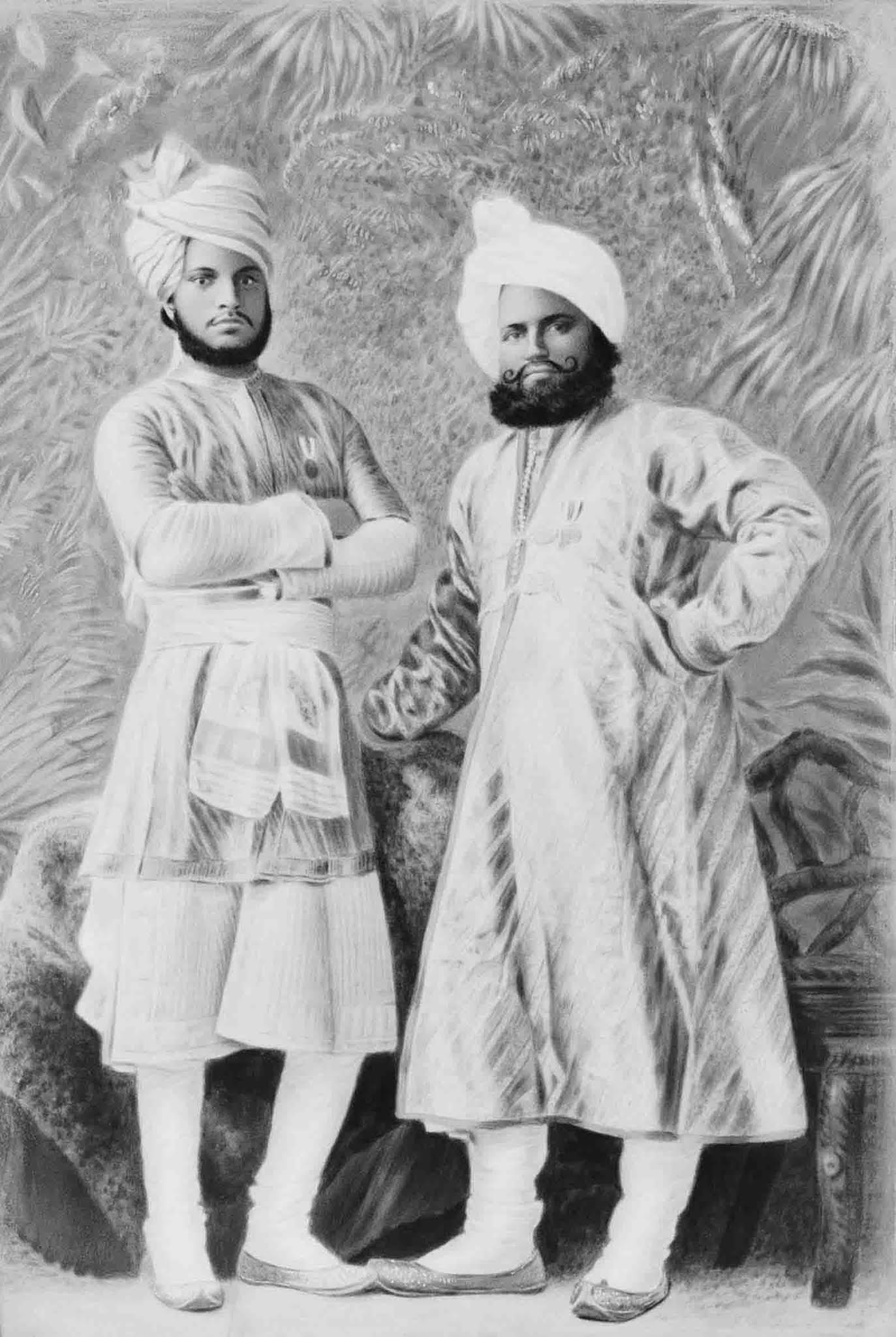

fter the Queen passed away, the family evicted Karim from the home the queen had given him and deported him back to India. The unusual friendship between the Queen and her Indian servant began in 1887 and spanned for 14 years. Mohammed Abdul Karim was born into a Muslim family at Lalitpur near Jhansi in 1863. He was taught Persian and Urdu privately and, as a teenager, traveled across North India and into Afghanistan. He eventually secured a clerk position at a jail in Agra, one where his father and the brothers of his soon-to-be wife both worked. It was there that Karim was handpicked to serve the somewhat recently christened Empress of India, Queen Victoria. The Queen had expressed interest in the Indian territories ahead of her Golden Jubilee in 1887 and specifically requested Indian staff members help serve at a banquet for heads of state. As such, Karim, was one of two servants selected and presented to Victoria as “a gift from India” on the occasion of her 50th year on the throne.

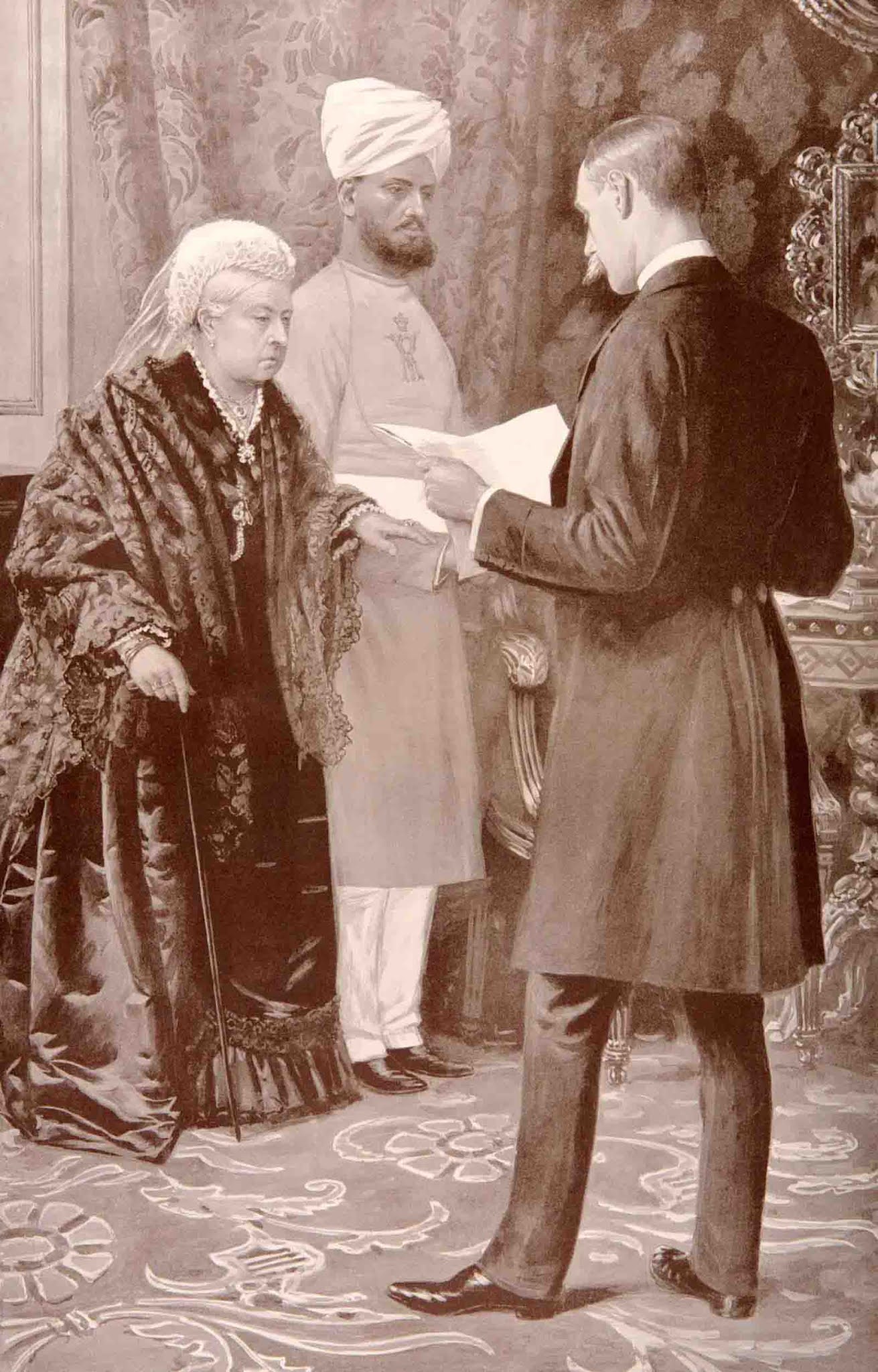

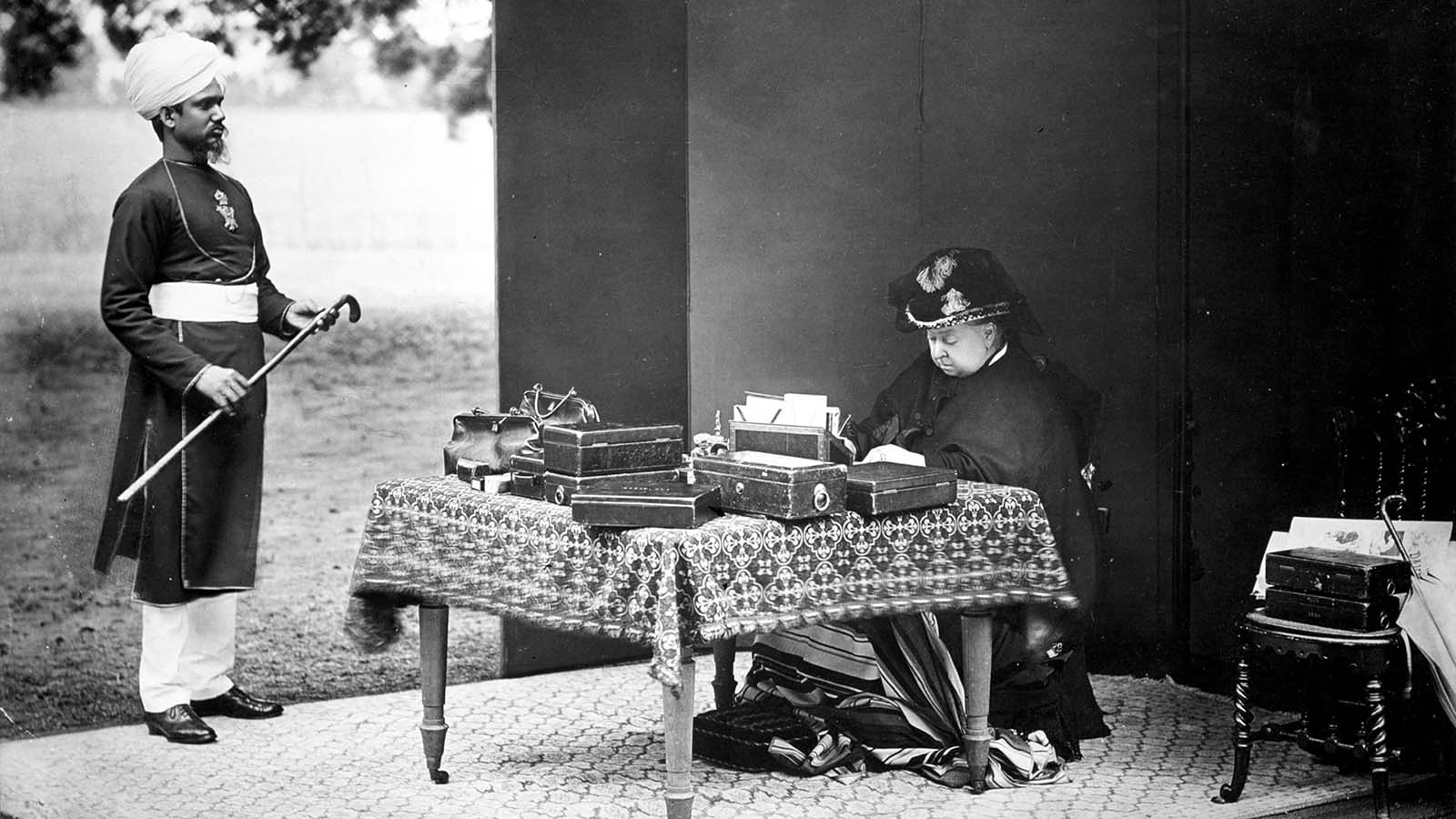

After a journey by rail from Agra to Bombay and by mail steamer to Britain, Karim and the other servant arrived at Windsor Castle in June 1887. They were put under the charge of Major-General Dennehy and first served the Queen at breakfast in Frogmore House at Windsor on 23 June 1887. The Queen described Karim in her diary for that day: “The other, much younger, is much lighter [than Buksh], tall, and with a fine serious countenance. His father is a native doctor at Agra. They both kissed my feet.” Five days later, the Queen noted that “The Indians always wait now and do so, so well and quietly.” On 3 August, she wrote: “I am learning a few words of Hindustani to speak to my servants. It is a great interest to me for both the language and the people, I have naturally never come into real contact with before.” On 20 August she had some “excellent curry” made by one of the servants. By 30 August Karim was teaching her Urdu, which she used during an audience in December to greet the Maharani Chimnabai of Baroda.

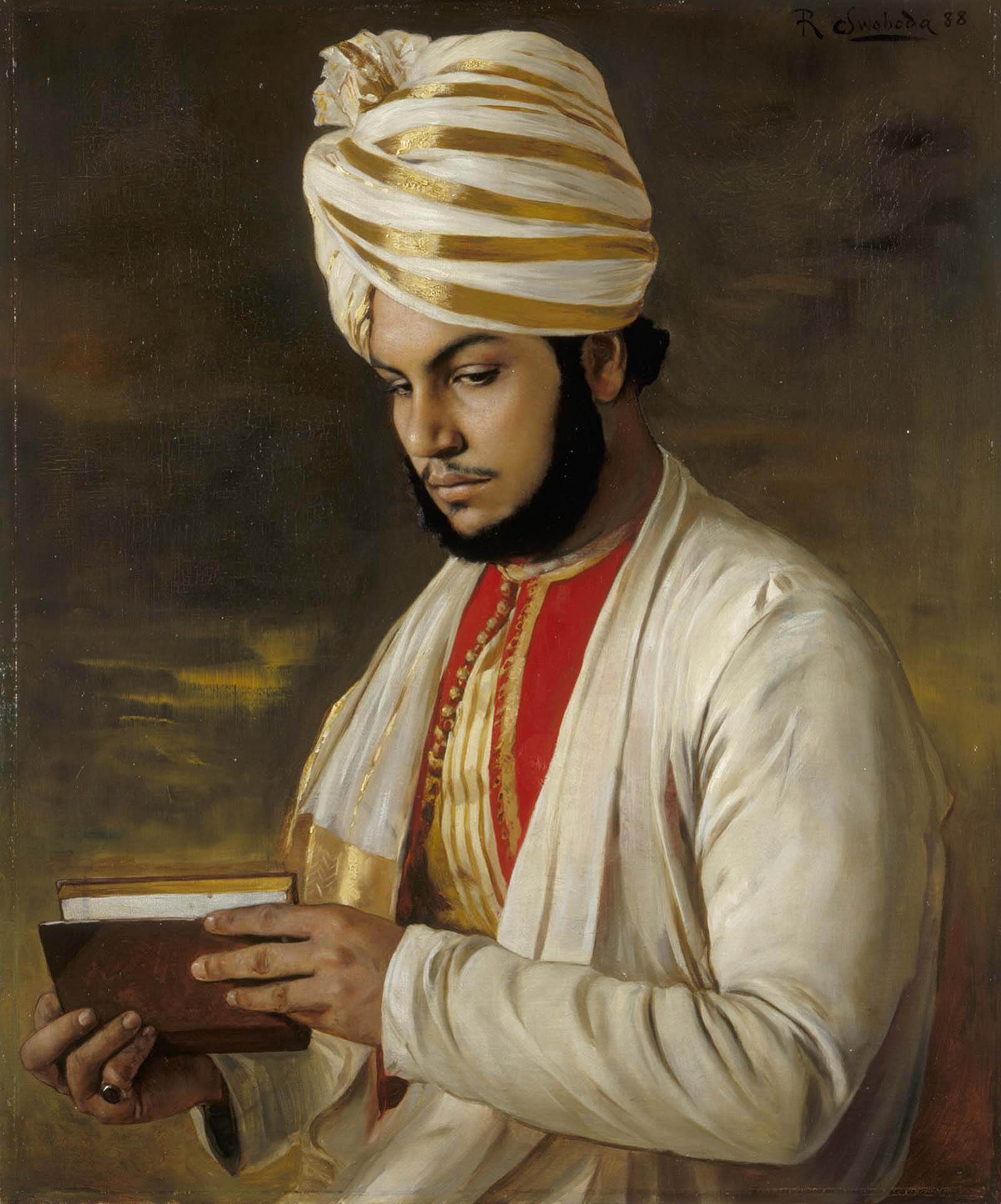

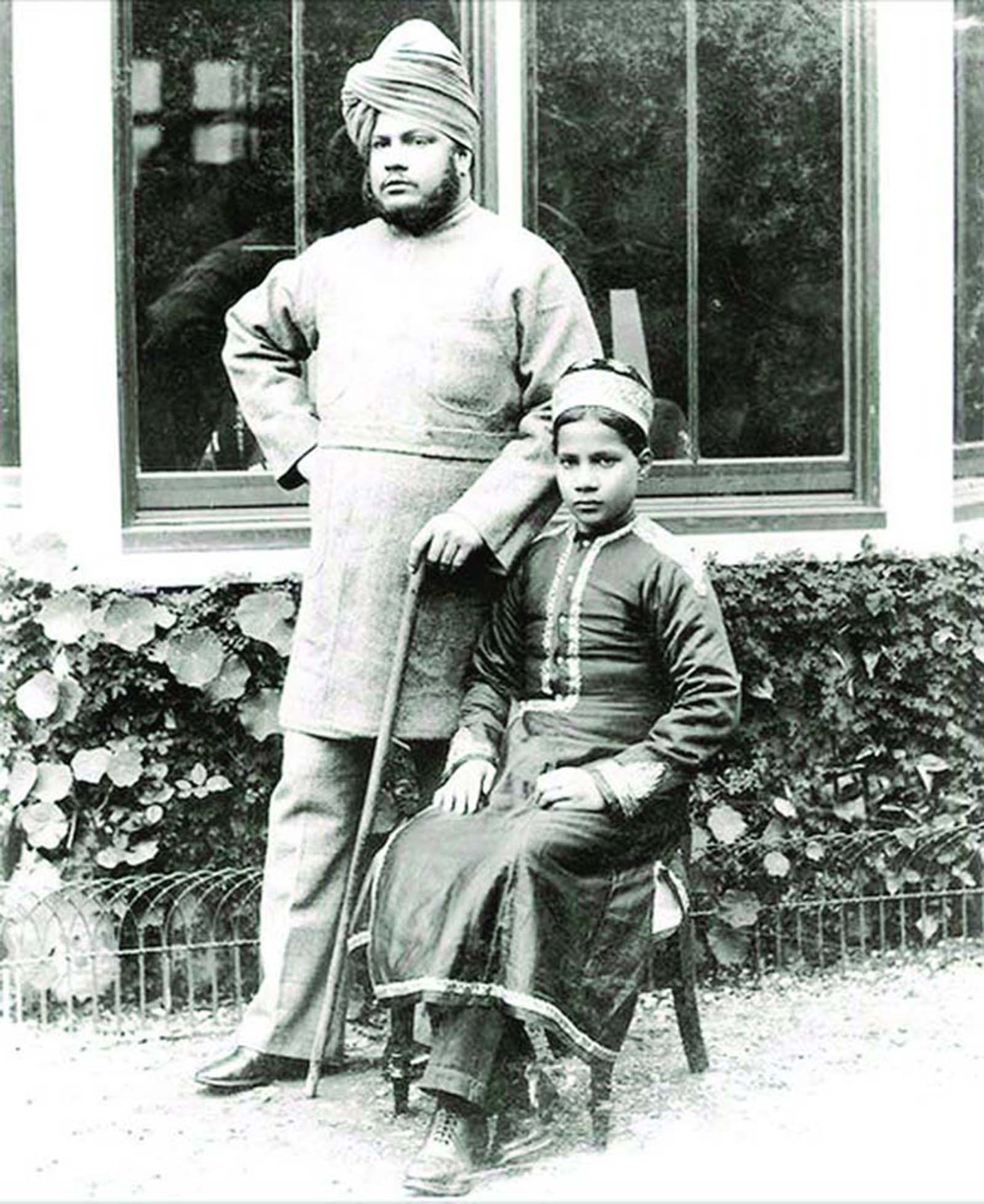

Victoria took a great liking to Karim and ordered that he was to be given additional instruction in the English language. By February 1888 he had “learnt English wonderfully” according to Victoria. After he complained to the Queen that he had been a clerk in India and thus menial work as a waiter was beneath him, he was promoted to the position of “Munshi” in August 1888. In her journal, the Queen writes that she made this change so that he would stay: “I particularly wish to retain his services as he helps me in studying Hindustani, which interests me very much, & he is very intelligent & useful.” Photographs of him waiting at the table were destroyed and he became the first Indian personal clerk to the Queen. Buksh (the other servant) remained in the Queen’s service, but only as a khidmatgar or table servant, until his death at Windsor in 1899. According to Karim biographer Sushila Anand, the Queen’s own letters testify that “her discussions with the Munshi were wide-ranging—philosophical, political, and practical. Both head and heart were engaged. There is no doubt that the Queen found in Abdul Karim a connection with a world that was fascinatingly alien, and a confidant who would not feed her the official line.” Karim was placed in charge of the other Indian servants and made responsible for their accounts. Victoria praised him in her letters and journal. “I am so very fond of him” she wrote, “He is so good & gentle & understanding all I want & is a real comfort to me.” She admired “her personal Indian clerk & Munshi, who is an excellent, clever, truly pious & very refined gentleman, who says, ‘God ordered it’ … God’s Orders is what they implicitly obey! Such faith as theirs & such conscientiousness set us a great example.” At Balmoral Castle, the Queen’s Scottish estate, Karim was allocated the room previously occupied by John Brown, a favorite servant of the Queen who had died in 1883. Despite the serious and dignified manner that Karim presented to the outside world, the Queen wrote that “he is very friendly and cheerful with the Queen’s maids and laughs and even jokes now—and invited them to come and see all his fine things offering them fruit cake to eat”. The queen not only allowed the Munshi to bring his wife over to England but hosted his father and other family members. Karim enjoyed his own personal carriage and the best seats at the opera. This developing relationship alarmed members of the court. Abdul was a Muslim and a servant and yet he was closer to the Queen than anyone else in her immediate circle. Four decades his senior, Victoria brought Abdul with her on all her trips and treated him as a close companion. They thought she had lost her mind, or at least tried very hard to insinuate she had. But Victoria defended her protegee, even giving him a generous land grant in India. According to Shrabani Basu, the journalist who uncovered this friendship and wrote the Victoria & Abdul: The True Story of the Queen’s Closest Confidant: “In letters to him over the years between his arrival in the U.K. and her death in 1901, the queen signed letters to him as ‘your loving mother’ and ‘your closest friend. On some occasions, she even signed off her letters with a flurry of kisses—a highly unusual thing to do at that time. It was unquestionably a passionate relationship—a relationship which I think operated on many different layers in addition to the mother-and-son ties between a young Indian man and a woman who at the time was over 60 years old.” Though Victoria and Karim did spend a night alone at Glassat Shiel—the remote cottage in Scotland the queen had shared with John Brown—Basu does not think that the two, separated by decades in age, had a physical relationship. Karim’s descendants similarly believe that the relationship was platonic and maternal at best. In her final wishes before passing away, Queen Victoria was quite explicit: Karim would be one of the principal mourners at her funeral, an honor afforded only to the monarch’s closest friends and family. Victoria could not control what happened to the Munshi from beyond the grave, but she did everything in her power to mitigate the harsh treatment she presumed her family would inflict upon him. Upon her death on January 22, 1901, Victoria’s children worked swiftly to evict their mother’s favorite adviser. Edward VII sent guards into the cottage Karim shared with his wife, seizing all letters from the queen and burning them on the spot. They instructed Karim to return to India immediately, without fanfare or farewell. Karim subsequently lived quietly near Agra, on the estate that Victoria had arranged for him, until his death at the age of 46.

Until the publication of Frederick Ponsonby’s memoirs in 1951, there was little biographical material on the Munshi. Scholarly examination of his life and relationship with Victoria began around the 1960s, focusing on the Munshi as “an illustration of race and class prejudice in Victorian England”. Mary Lutyens, in editing the diary of her grandmother Edith (wife of Lord Lytton, Viceroy of India 1876–80), concluded, “Though one can understand that the Munshi was disliked, as favorites nearly always are … One cannot help feeling that the repugnance with which he was regarded by the Household was based mostly on snobbery and color prejudice.” Victoria biographer Elizabeth Longford wrote, “Abdul Karim stirred once more that same royal imagination which had magnified the virtues of John Brown … Nevertheless, [it] insinuated into her confidence an inferior person, while it increased the nation’s dizzy infatuation with an inferior dream, the dream of Colonial Empire.” (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / British Public Archives / VanityFair / BBC / Victoria & Abdul: The True Story of the Queen’s Closest Confidant). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe