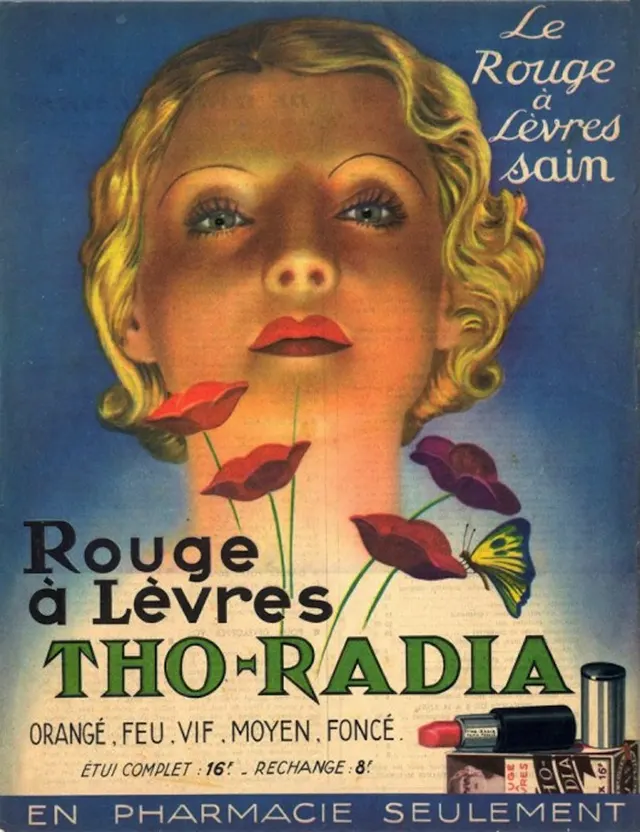

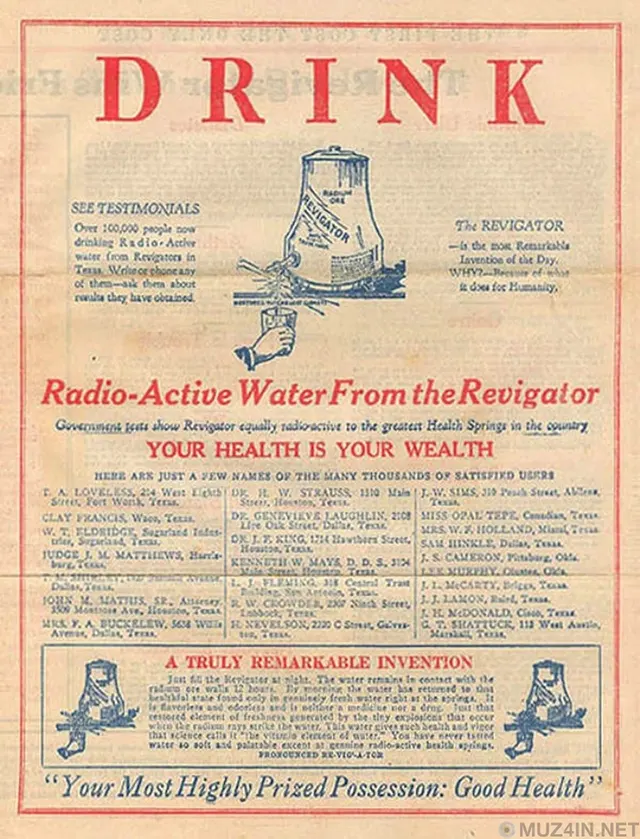

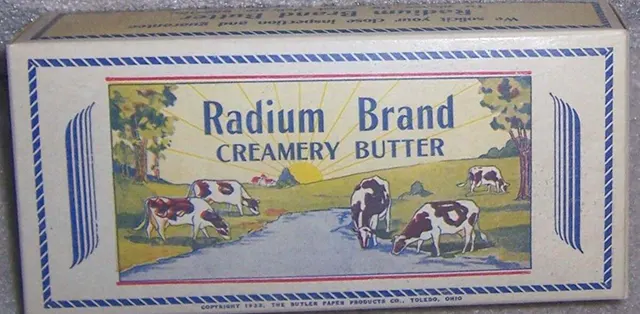

In the early 20th century, radium paint was used on numerous household items without a second thought. However, that changed when factory workers, who were frequently exposed to radium paint, began to fall ill and die. These workers, known as the Radium Girls, often succumbed to radiation poisoning, while others fought against it. They ultimately won, but the victory came at a great cost. When radium was first discovered, it was believed to have health benefits. Radioactive treatments were popular, and the harmful effects of radium were not yet understood. Dangerous X-rays conducted at the time further exacerbated the effects of this radioactive quackery, so if you had been exposed to the poison, seeing a doctor made it worse. When the Radium Girls discovered their sickness, they bravely fought against the corporations responsible for their plight. These women are remembered as heroic and tragic figures in history, and their bravery led to stricter regulations, protecting countless others from similar fates. Radium was discovered by Marie Curie and her husband, Pierre Curie, in 1898. The discovery was a result of their ongoing research into the properties of uranium, which led them to investigate the residual materials left after the extraction of uranium ore. They discovered that these materials were still highly radioactive, suggesting the presence of an unknown element. They named it radium, derived from the Latin word “radius,” meaning ray, due to its highly radioactive nature. Radium, hailed for its luminescent properties, found its way into self-luminous paints used in a range of items, from watches to aircraft switches, clocks, and instrument dials. Just a tiny speck of radium, about 1 microgram, could make a watch glow in the dark. One of these patented special radium-based paints was invented by William J. Hammer. Hammer’s recipe was used by the US Radium Corporation during the First World War to produce Undark, a high-tech paint which allowed America’s infantrymen to read their wristwatches and instrument panels at night. They also marketed the pigment for non-military products such as house numbers, pistol sights, light switch plates, and glowing eyes for toy dolls. Despite growing awareness of the dangers of radium, the company reassured the public that their paint contained such minuscule amounts of the radioactive element that it was harmless. While this was true of the products themselves, the amount of radium present in the dial-painting factory was much more dangerous, unbeknownst to the workers there. The U.S. Radium Corporation hired approximately 70 women to perform various tasks involving radium, while the owners and scientists, aware of radium’s effects, took great care to avoid exposure. Chemists at the plant used lead screens, tongs, and masks. The company even distributed literature to the medical community describing the “injurious effects” of radium. Across the U.S. and Canada, an estimated 4,000 workers were hired to paint watch faces with radium. At USRC, each painter mixed her own paint in a small crucible and then used camel hair brushes to apply the glowing paint onto dials. The rate of pay was about a penny and a half per dial (equivalent to $0.357 in 2023), earning the girls $3.75 (equivalent to $89.18 in 2023) for painting 250 dials per shift. The brushes would lose shape quickly, so factory supervisors encouraged their workers to point the brushes with their lips (“lip, dip, paint”), or use their tongues to keep them sharp. Unaware of the true nature of radium, the Radium Girls also painted their nails, teeth, and faces with the deadly paint produced at the factory for fun. Dentists were among the first to witness the alarming effects of radium exposure on dial painters. They noticed a range of issues, from dental pain and loose teeth to lesions, ulcers, and even the failure of tooth extractions to heal properly. As time passed, these women began to suffer from more severe conditions such as anemia, bone fractures, and the dreaded “radium jaw,” where the jawbone deteriorates. The women also experienced suppression of menstruation, and sterility. Shockingly, the very X-ray machines used by medical investigators to study these conditions may have worsened the workers’ health by subjecting them to additional radiation. Despite these findings, doctors, dentists, and researchers complied with requests from the companies not to release their data. In 1923, the first dial painter died, and before her death, her jaw fell away from her skull. By 1924, 50 women who had worked at the plant were ill, and a dozen had died. At the urging of the companies, medical professionals attributed worker deaths to other causes. Syphilis, a notorious sexually transmitted infection at the time, was often cited in attempts to smear the reputations of the women. Plant worker Grace Fryer made the courageous decision to take legal action against U.S. Radium, but finding a lawyer willing to challenge the powerful corporation proved to be a daunting task. It took two years for Fryer and her colleagues to secure legal representation. Even then, the litigation process moved slowly. When the case finally reached court in January 1928, the toll of radium poisoning was evident. Two women were so ill they were confined to their beds, and none of them could lift their arms to take the oath. Five factory workers, including Grace Fryer, Edna Hussman, Katherine Schaub, and sisters Quinta McDonald and Albina Larice, joined forces in the lawsuit, becoming known as the Radium Girls. The legal battle, accompanied by intense media scrutiny, led to the establishment of significant legal precedents and the implementation of regulations governing labor safety standards. These regulations included the recognition of a baseline level of “provable suffering”. Concurrently, in Illinois, five other women employed by the Radium Dial Company (unrelated to the U.S. Radium Corporation) also filed suit against their employer. The story of the Radium Girls occupies a significant chapter in the history of health physics and the labor rights movement. The right of individual workers to sue for damages from corporations due to labor abuse was established as a result of the Radium Girls’ case. In the wake of the case, industrial safety standards were demonstrably enhanced for many decades. The Radium Girls’ case was settled in the autumn of 1928, before the trial was deliberated by the jury, and the settlement for each of the Radium Girls was $10,000 (equivalent to $177,000 in 2023) and a $600 per year annuity (equivalent to $10,600 in 2023) paid $12 a week (equivalent to $200 in 2023) for all of their lives while they lived, and all medical and legal expenses incurred would also be paid by the company. The lawsuit and the resulting media coverage were instrumental in shaping occupational disease labor laws. As a direct result, radium dial painters were trained in proper safety protocols and provided with protective gear. Specifically, they were no longer allowed to shape paintbrushes with their lips and were instructed to avoid ingesting or inhaling the paint. Remarkably, radium paint remained in use for dials as late as the 1970s. Nearly a century has passed since these women were afflicted with radium poisoning, yet the radium they were exposed to remains. With a half-life of 1,600 years, the radium still exists in their remains. In a sobering discovery, when a scientist used a Geiger counter near the graves of some of the Radium Girls, it detected radioactivity in their bodies, indicating that they still emit a glow from the ground to this day. (Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Britannica). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe