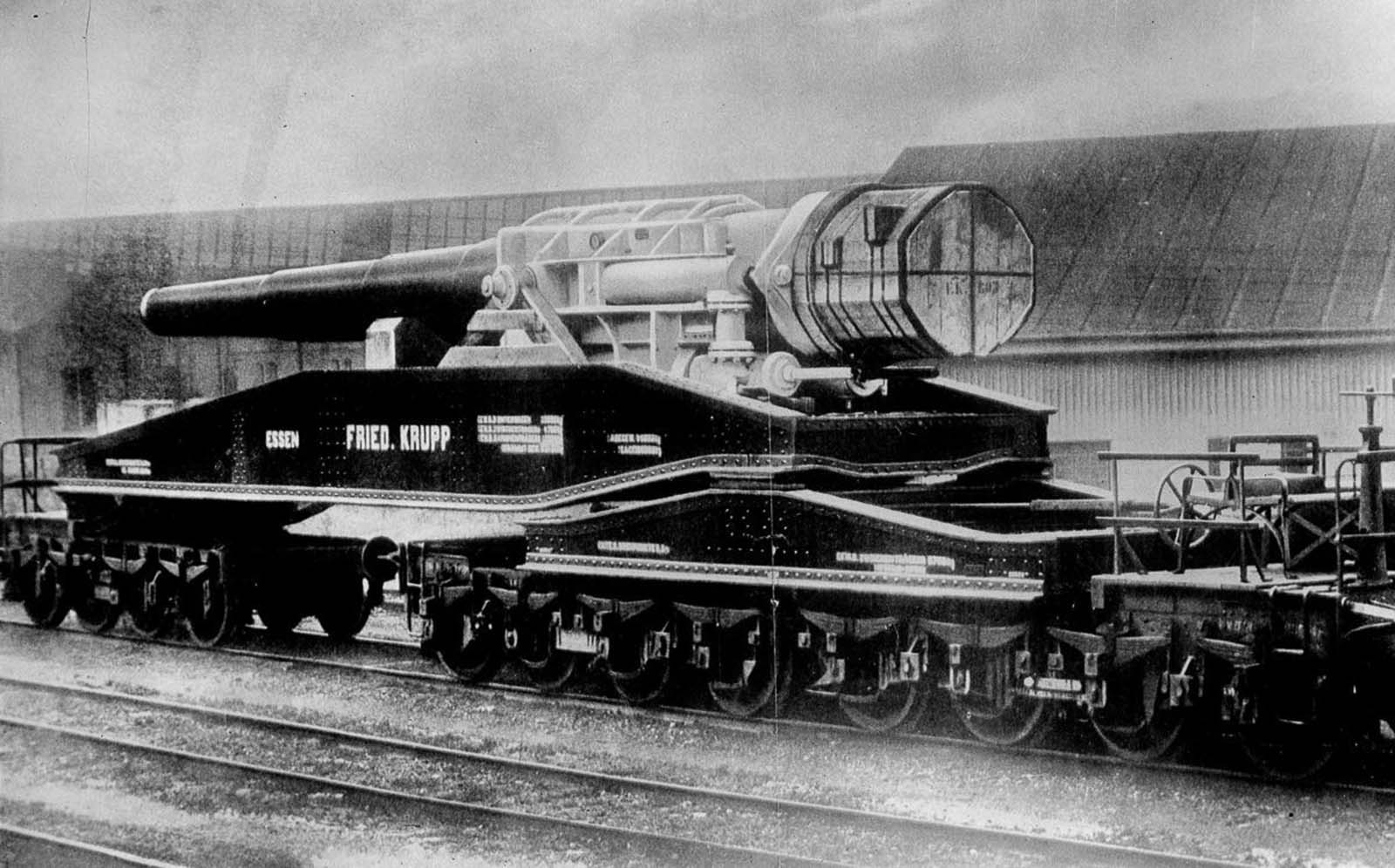

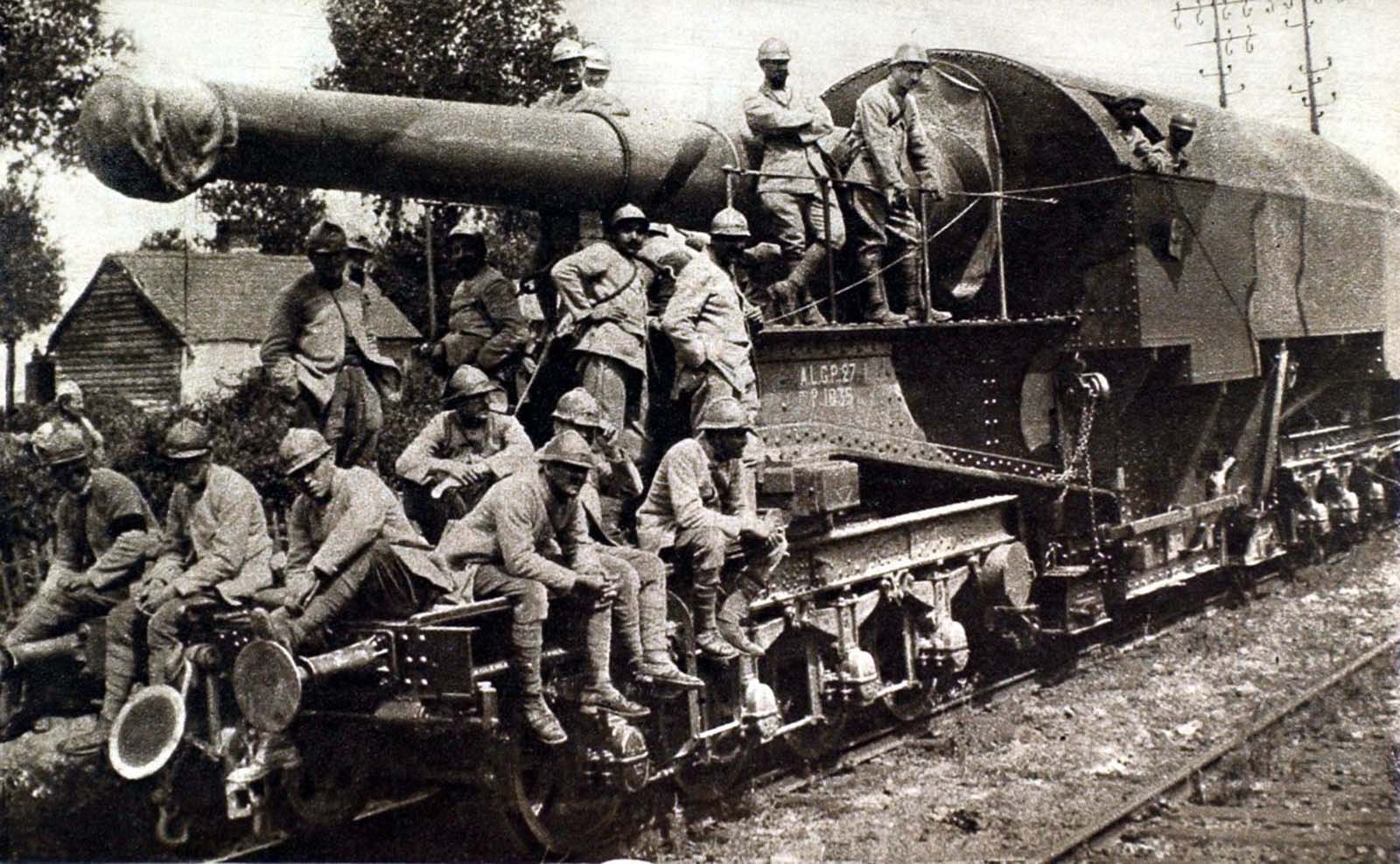

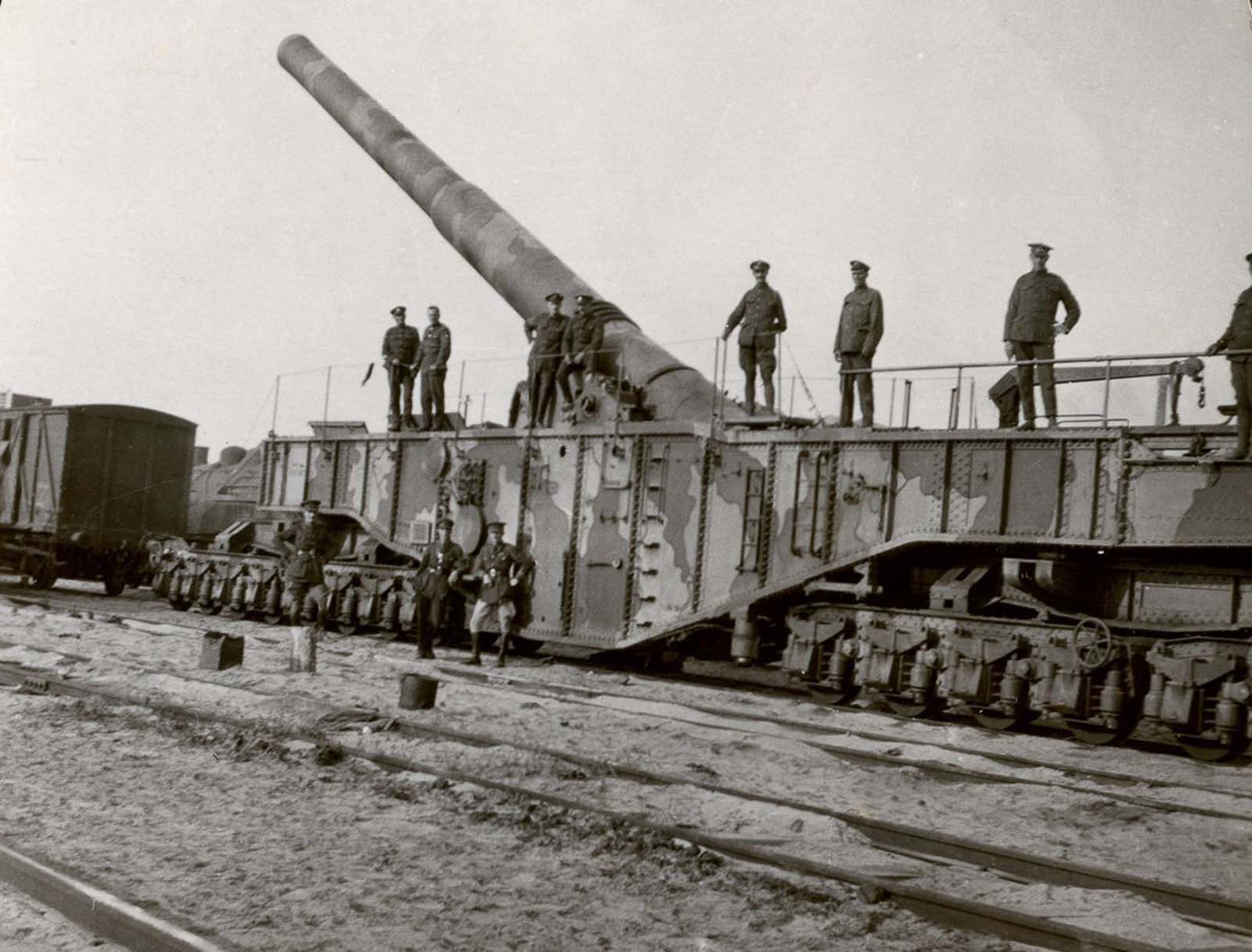

Railroad guns had a shorter life span than other practical military technologies spawned during the American Civil War, such as submarines, repeating rifles, and machine guns. Yet from 1862 to 1945, they earned a reputation as a bunker buster without equal and terrorized civilians by firing on cities from afar, without warning. Mounting heavy artillery on mobile railroad cars was first proposed by Russian Gustav Kori in 1847, and was first used in combat in the American Civil War. Confederates bolted a 32-pounder Brooke naval rifle to a flatcar protected by an iron casemate, the finished car looking much like a land version of the ironclad CSS Virginia. It engaged in artillery duels before the Battle of Fair Oaks. The Union used similar railroad mountings during the 1864 siege of Petersburg. The most famous of these was Dictator, a thirteen-inch seacoast mortar on an eight-wheeled flatcar. Lobbing 218-pound shells as far as forty-two hundred yards, this behemoth bombarded Southern batteries and bombproofs with telling effect. Apart from experiments conducted by the French during the siege of Paris in 1870 and by the British Royal Navy’s Capt. John Fisher (of Dreadnought fame) in 1881 and 1882, there were few advancements in railroad guns until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when French firms experimented with mounting large artillery pieces—originally designed as the main armament of warships—on large railroad carriages. The French so emplaced not only 320mm guns and 200mm howitzers but even pieces as small as 155mm howitzers. During the war to come, naval or coast artillery crews would man many such railroad guns. The German and Austro-Hungarian militaries were also experimenting, in the greatest secrecy, on mammoth siege guns—Krupp’s 420mm Dicke Bertha (Big Bertha) and Skoda’s 305mm Schlanke Emma (Skinny Emma) howitzers—which were later deployed with admirable accuracy and power against Belgian and French fortifications. The limitations of Europe’s road networks, coupled with the French experiments in railroad guns, may have encouraged Germany to combine the technical strengths of Krupp’s artillery bureau with those of the Eisenbahnpioniere, perhaps the most impressive and professional military rail service in Europe at the time. By the end of World War I, railroads were regarded as the preeminent method for fielding super-heavy artillery. By Armistice Day, the U.S. Coast Artillery had deployed seventy-one railroad guns in ten regiments in Europe. They ranged in size from fourteen-inch weapons to 190mm. Almost all were made in France. The pinnacle of railroad artillery’s long-range role was the Pariskanone, or Paris gun. Misidentified as “Big Bertha” by Parisians, it was officially named the Wilhelmgeschütz in the kaiser’s honor. Actually, a series of replaceable gun tubes, the Paris guns were developed by Rausenberger’s team in cooperation with the German navy. With a 280mm naval gun as a base, each barrel was sleeved down to 210mm or, later, using reconditioned barrels, to 240mm. The modified tubes were then extended and heavily braced. Each tube could fire only twenty to fifty shells before its rifling and accuracy deteriorated substantially. During World War II, Germany was the premier builder and user of super-heavy railroad guns. Allied intelligence identified some twelve different types of German-made railway artillery, ranging from 150mm to 800mm, by 1945. Captured Czech and French pieces were also widely used. Germans based 280mm guns on Cap Griz Nez, on the northern coast of France, in 1940 to batter the English coast and provide cover for the abortive Operation Sealion. Because such weapons were impossible to camouflage well, the Nazis’ Organisation Todt built gigantic, igloo-shaped bunkers to protect the guns, which still stands. In spite of the Red Army’s advance into Poland, the Germans continued to deploy railroad guns and Karl-series caterpillar-tracked mortars to pummel Warsaw during the Uprising of late summer 1944. Perhaps the most successful German railroad artillery was the 280mm K5(E) series of rail guns, of which some twenty-five units were built. Two of these 218-ton mammoths, Robert and Leopold (known to the Allies as “Anzio Express” and “Anzio Annie,” respectively), achieved infamy during the 1944 battles for Anzio. Firing 550-pound shells to a range of over thirty miles, these K5(E)s played havoc with beachhead operations but were only fired sporadically in the daylight, taking advantage of concealment in railway tunnels. Despite intelligence as to their positions, Allied air power never neutralized either gun and only occasionally interrupted ammunition supply trains. These photographs span the history of railway guns, from the very first used by Confederate forces in the American Civil War, to Autochrome photos of guns on the western front of World War I, to then near-obsolete behemoths of World War II. (Photo credit: Library of Congress / Getty Images / Text: The Quarterly Journal of Military History). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe