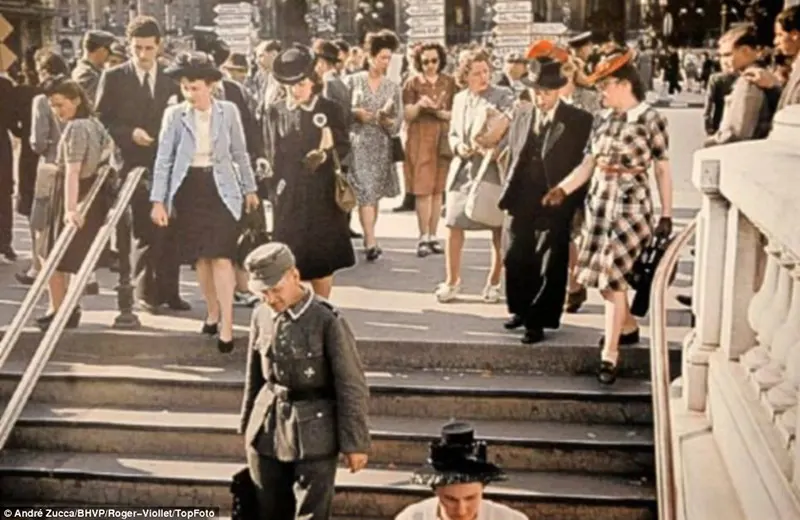

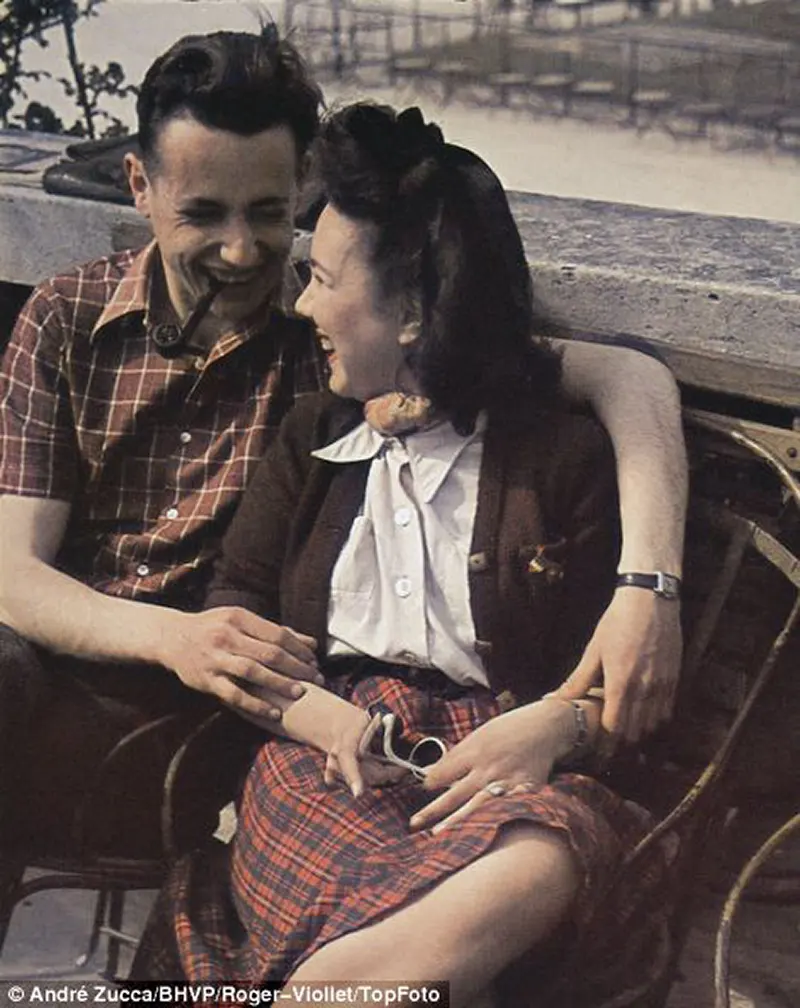

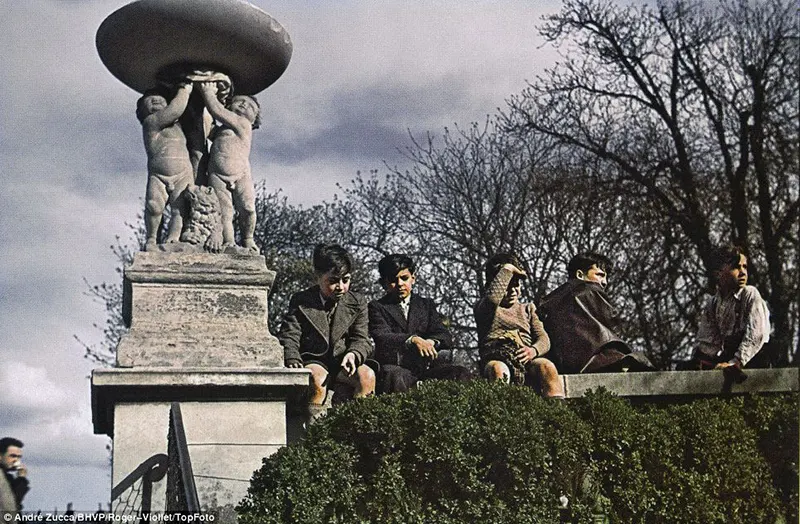

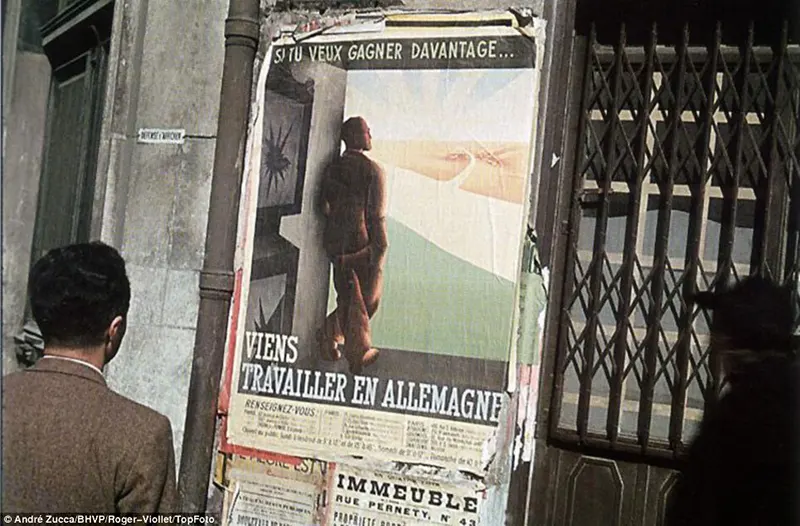

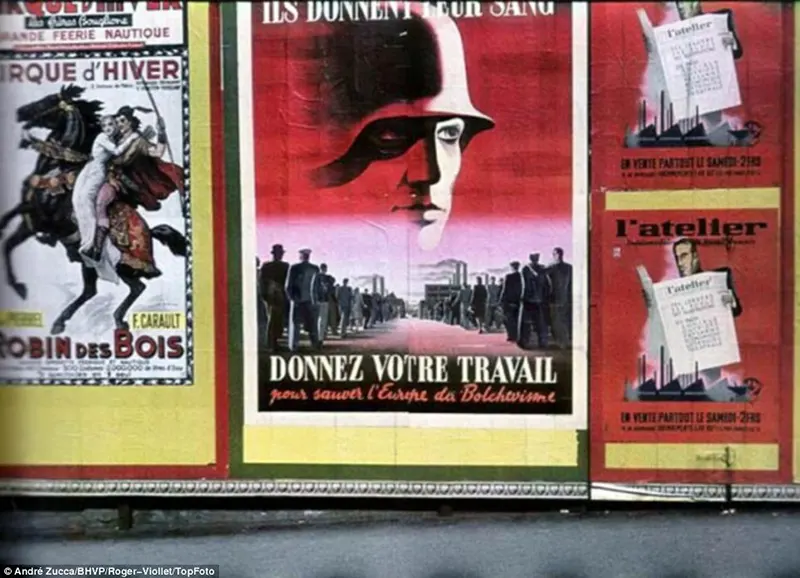

The shots depict fashionable young women and commuters mixed with German soldiers on the bustling Paris streets. The famous roads of the French capital are adorned with symbols of the German regime but Parisians appear jubilant. André Zucca was born in 1897 in Paris, the son of an Italian dressmaker. Zucca spent part of his youth in the United States before returning to France in 1915. Following the outbreak of World War I, he joined the French Army where he was wounded and decorated with the Croix de Guerre. After the war, he began a career as a photographer. In 1941, he was contracted by the occupying Germans to work as a photographer and correspondent for the magazine Signal, a propaganda organ of the German Wehrmacht. His photography was used to support a positive image of the German occupation in France, as well as to encourage French men to volunteer for the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism, a collaborationist French militia serving on the Eastern Front. It is disputed whether or not Zucca’s work for the Germans was linked to any ideological sympathies with Nazism, and some have argued he was a right-wing anarchist. In addition to his contributions to Signal, he was one of the few photographers in occupied Europe with access to Agfacolor film, a rare and expensive piece of color film at the time, thanks to his close relationship with the Germans. He is most well known today for his color photographs of daily life in Paris under German occupation. Following the liberation, he was placed on trial in October 1944 by the French Provisional Government in the épuration légale (legal purge), where his journalistic privileges were permanently revoked. The court ruled that no further legal action should be taken against Zucca, largely thanks to the credentials of a resistance member who spoke out on his behalf. With his journalism career in shambles, Zucca assumed the name André Piernic and settled in the French commune of Dreux, where he opened a small photo boutique, taking wedding and communion photos. He died in 1973. His photo collections were purchased by the Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris in 1986, consisting primarily of his photos of occupied Paris taken during World War II. During the Occupation, the French Government moved to Vichy, and Paris was governed by the German military and by French officials approved by the Germans. For Parisians, the Occupation was a series of frustrations, shortages, and humiliations. A curfew was in effect from nine in the evening until five in the morning; at night, the city went dark. Rationing of food, tobacco, coal, and clothing was imposed from September 1940. Every year the supplies grew more scarce and the prices higher. A million Parisians left the city for the provinces, where there was more food and fewer Germans. The French press and radio contained only German propaganda. The attitude of the Parisians toward the occupiers varied greatly. Some saw the Germans as an easy source of money; others, as the Prefect of the Seine, Roger Langeron (arrested on 23 June 1940), commented, “looked at them as if they were invisible or transparent.” The attitude of members of the French Communist Party was more complicated; the Party had long denounced Nazism and Fascism, but after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939, had to reverse direction. Finding food soon became the first preoccupation of the Parisians. The authorities of the German occupation transformed French industry and agriculture into a machine for serving Germany. Shipments to Germany had first priority; what was left went to Paris and the rest of France. All of the trucks manufactured at the Citroen factory went directly to Germany. The greatest share of shipments of meat, wheat, milk produce, and other agricultural products also went to Germany. The rationing system also applied to clothing: leather was reserved exclusively for German army boots, and vanished completely from the market. Leather shoes were replaced by shoes made of rubber or canvas (raffia) with wooden soles. A variety of ersatz or substitute products appeared, which were not exactly what they were called: ersatz wine, coffee (made with chicory), tobacco, and soap. Finding coal for heat in winter was another preoccupation. The Germans had transferred the authority over the coal mines of northern France from Paris to their military headquarters in Brussels. The priority for the coal that did arrive in Paris was for use in factories. Even with ration cards, adequate coal for heating was almost impossible to find. Supplies for normal heating needs were not restored until 1949. Paris restaurants were open but had to deal with strict regulations and shortages. Meat could only be served on certain days, and certain products, such as cream, coffee, and fresh produce were extremely rare. Nonetheless, the restaurants found ways to serve their regular clients. The historian René Héron de Villefosse, who lived in Paris throughout the war, described his experience: The great restaurants were only allowed to serve, under the fierce eye of frequent control, noodles with water, turnips, and beets, in exchange for a certain number of tickets, but the hunt for a good meal continued for many food-lovers. For five hundred francs one could conquer a good pork chop, hidden under cabbage and served without the necessary tickets, along with a liter of Beaujolais and a real coffee; sometimes it was on the first floor at rue Dauphine, where you could listen to the BBC while sitting next to Picasso.” Many Parisians collaborated with the Government of Marshal Pétain and with the Germans, assisting them with the city administration, the police, and other government functions. French government officials were given the choice of collaborating or losing their jobs. On September 2, 1941, all Paris magistrates were asked to take an oath of allegiance to Marshal Petain. Only one, Paul Didier, refused. Unlike the territory of Vichy France, governed by Marshal Pétain and his ministers, the document of surrender placed Paris in the occupied zone, directly under German authority. Following the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, the French Resistance in Paris launched an uprising on August 19, seizing the police headquarters and other government buildings. The city was liberated by French and American troops on August 25; the next day, General de Gaulle led a triumphant parade down the Champs-Élysées on August 26, and organized a new government. In the following months, ten thousand Parisians who had collaborated with the Germans were arrested and tried, eight thousand convicted, and 116 executed.

(Photo credit: André Zucca / Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris / Wikimedia Commons / TopFoto / Captions from Daily Mail UK). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)