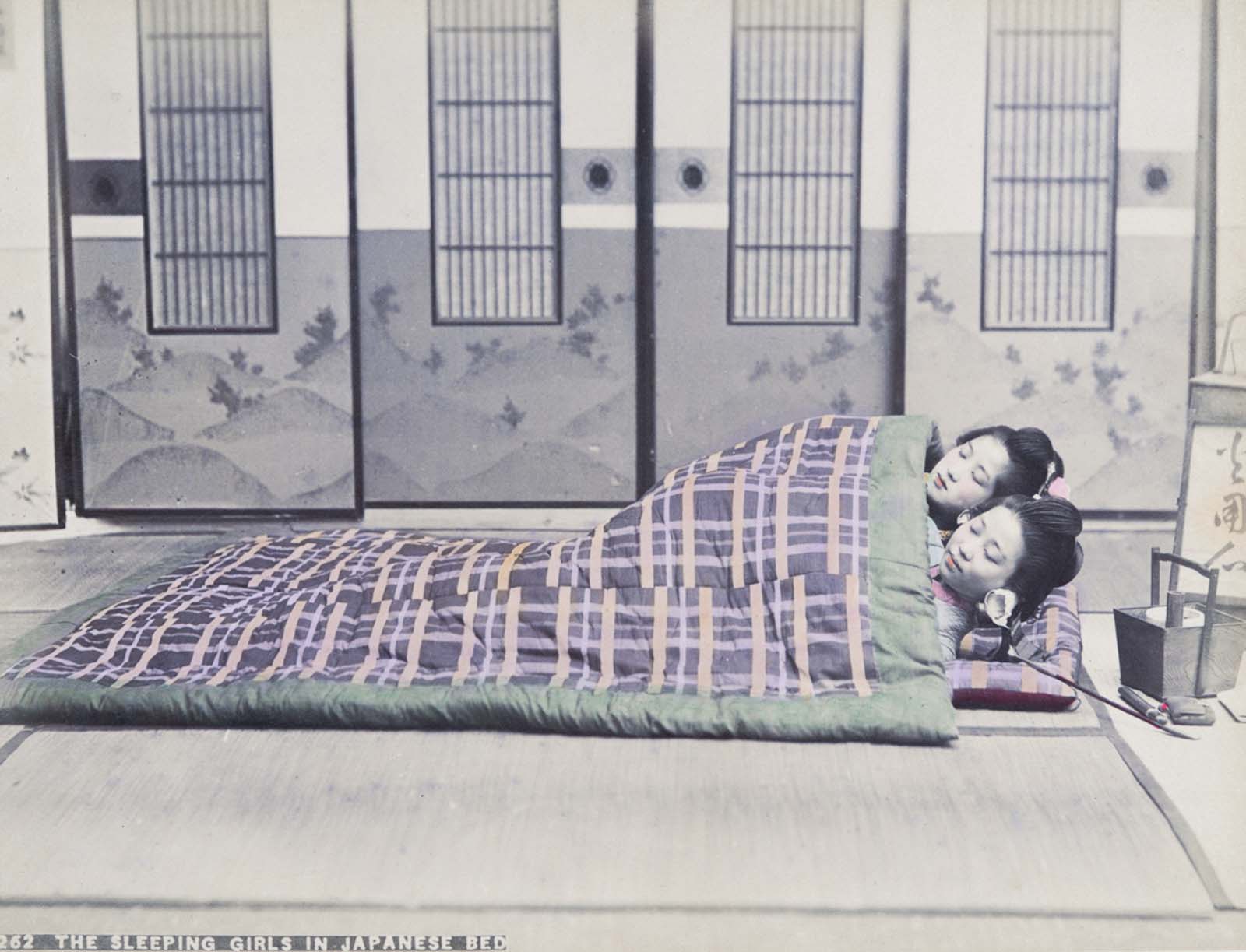

On July 8, 1853, the “black ships of evil mein” billowing smoke and riding without oar or sail were first seen off of Edo harbor. The mission was to be the defining point at the end of the feudal period and the beginning of the new age. In the words of the Emperor’s reply to the President the following spring, “we are governed by imperative necessity.” Japan could no longer isolate itself from the rest of the world. Already struggling with a weak economy, a failing feudalist structure, as well as a lineage dispute, the shogunate finally lost the confidence of the people when it could not turn back the barbarians. February 1854 saw the opening of the ports at Shinoda and Hakodate. Townsend Harris arranged a treaty with Japan in 1858 for trade rights with the U.S, and gradually more ports opened not only to America but Britain, France, the Netherlands, Russia, and the other Western countries. Xenophobia and economic hardship caused by the foreigners led to violent protests and the rise of extremists who abhorred the ineffectiveness of the current political situation. Ultimately, the dissatisfaction of the daimyo with the Tokugawa led to a military coup which overthrew the shogun. Under the Meiji Emperor the old feudal systems were dismantled and the nation looked toward the West for a new ideal. In order to consolidate power the new government abolished the han in 1871 and re-divided the country into prefectures. The government dismantled the samurai class by raising its own conscripted national army where commoner and samurai fought side by side and by outlawing the carrying of swords in 1876. Commoners were now allowed to take a surname and were free from any labor or travel restrictions. Although not without its problems, the Meiji Era was remembered as one of hope and discovery; the source of both was the endless menagerie of all things Western. The Meiji Restoration, as the event came to be known, marked the start of Japan’s ambitious rise to a global power that, for the first time in history, would see an Asian country stand shoulder-to-shoulder with European powers. Many of the Japanese were quick to adopt western style both in their appearance and actions. For example, the traditional Japanese haircut for males was the chom’mage. This called for the head to be shaved except for the rear, which was then pulled up and folded over the top of the head. Thanks to its high maintenance and uncomfortable nature, it did not take long for many men to switch to western hairstyles, especially those men who were engaged in the new professions like school teacher, policeman, or Meiji official. As with hairstyles, it was people in the new professions and the army who took the lead in adopting western clothes. Even then, in the cities, it was not uncommon to see someone in a kimono with western shoes or in an obi worn with spectacles and an umbrella. Traditional clothes remained in place though for those engaged in traditional roles such as farming or fishing. It took a longtime for the new ways to penetrate the countryside because there was little reason to change, and actually, many of the changes in the villages came from veterans returning from service and the young who had gone to the city. The original photographer behind these hand-colored amazing prints of Japan in the 1890s is unknown. The photos are part of a large photo collection held by the New York Public Library, and range from posed images of domestic life to breathtaking landscapes of Japan. (Photo credit: New York Public Library / Text: Josh Kilgore / Shibusawa, Keizo. Japanese Life and Culture in the Meiji Era. Tokyo: Tokyo Bunko, 1969 / Yamagida, Kunio. Japanese Manners and Customs in the Meiji Era. Tokyo: Tokyo Bunko, 1969). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe