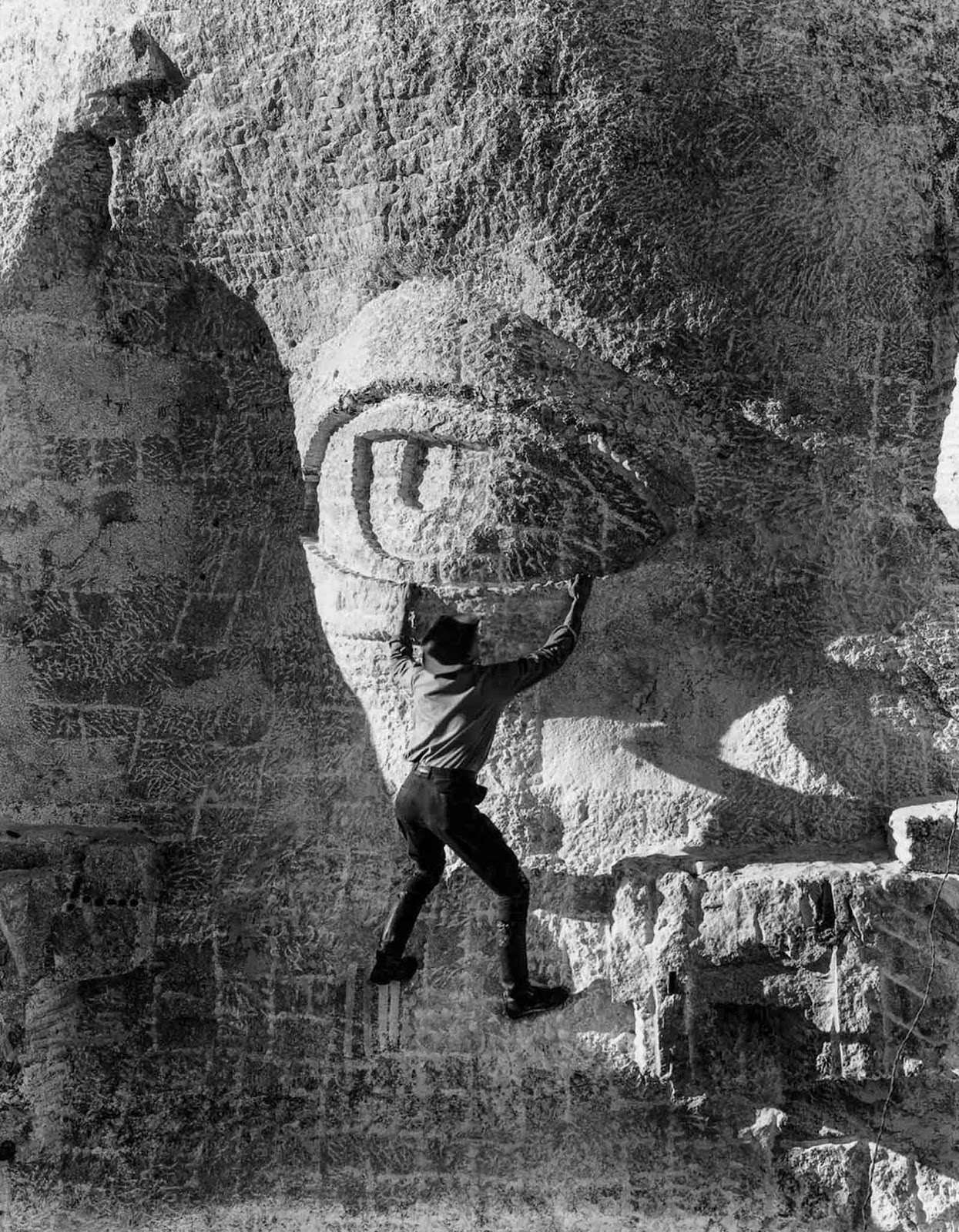

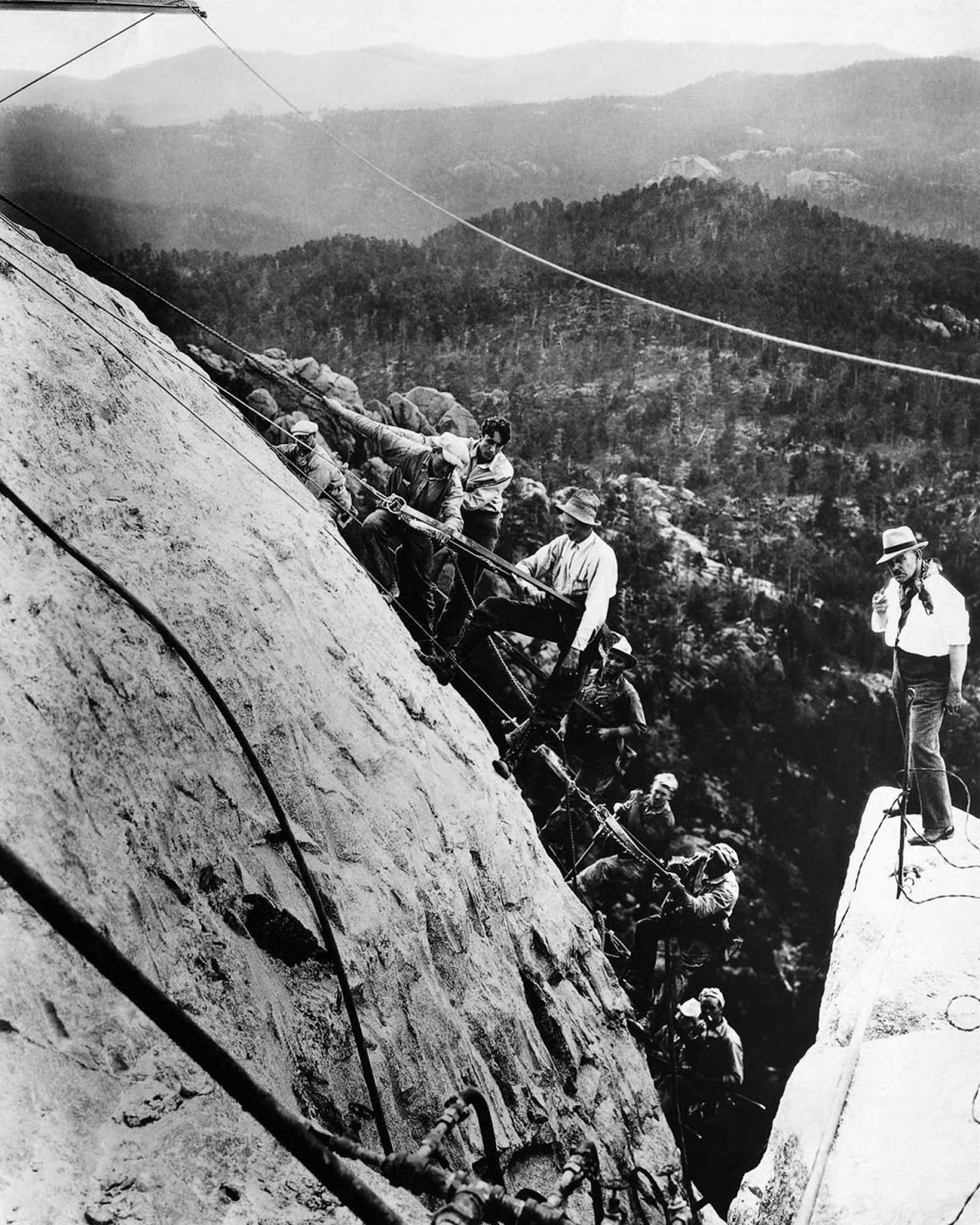

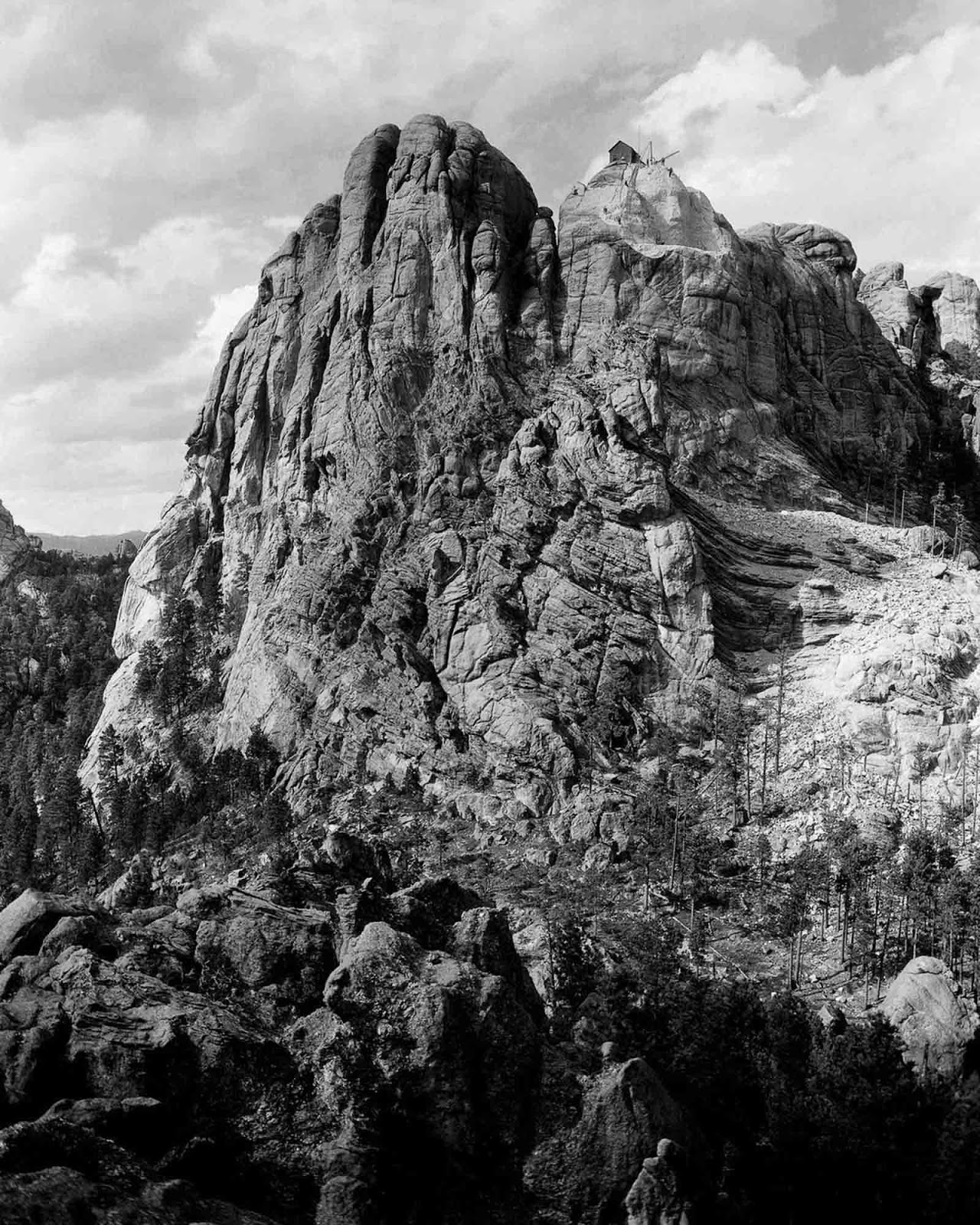

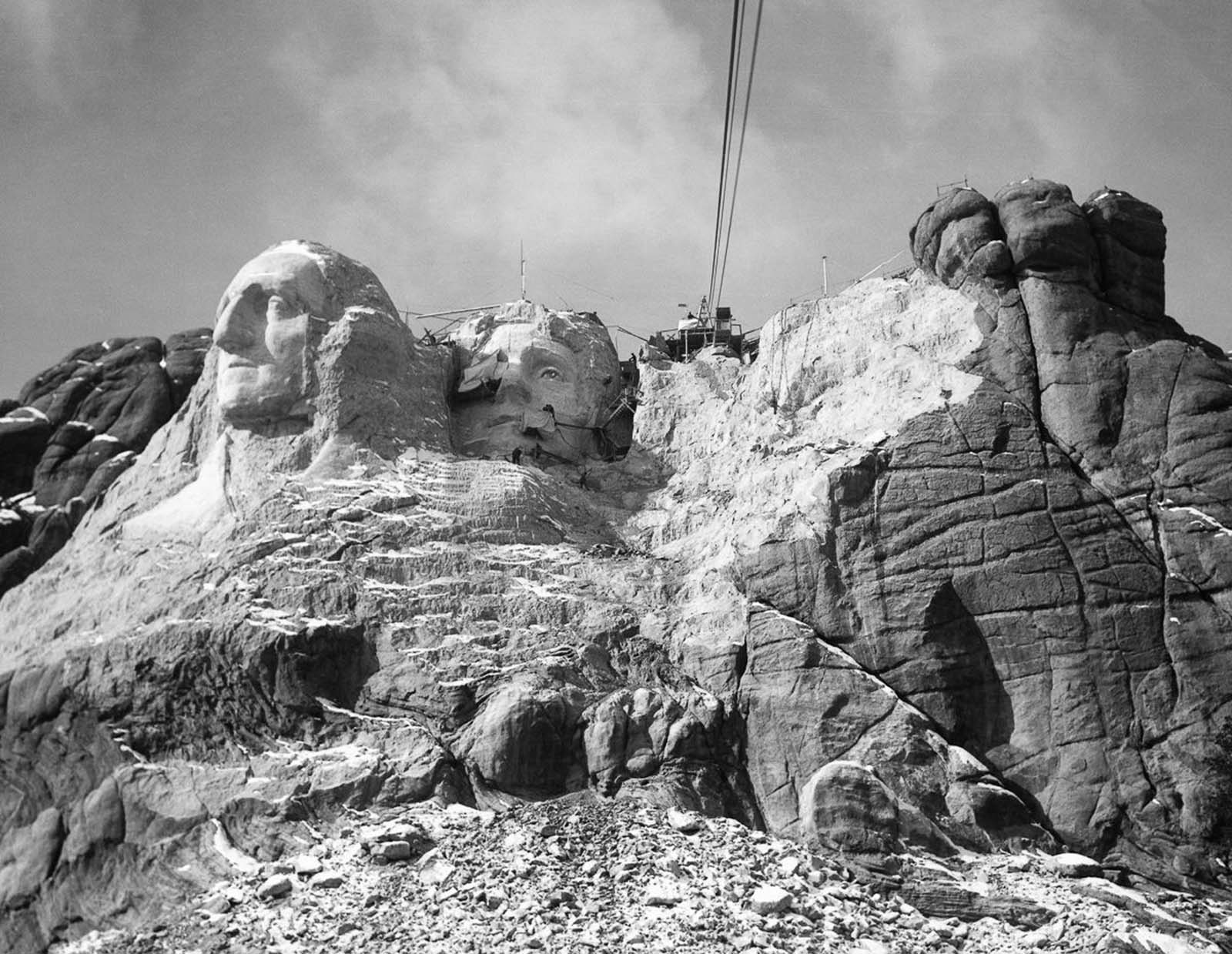

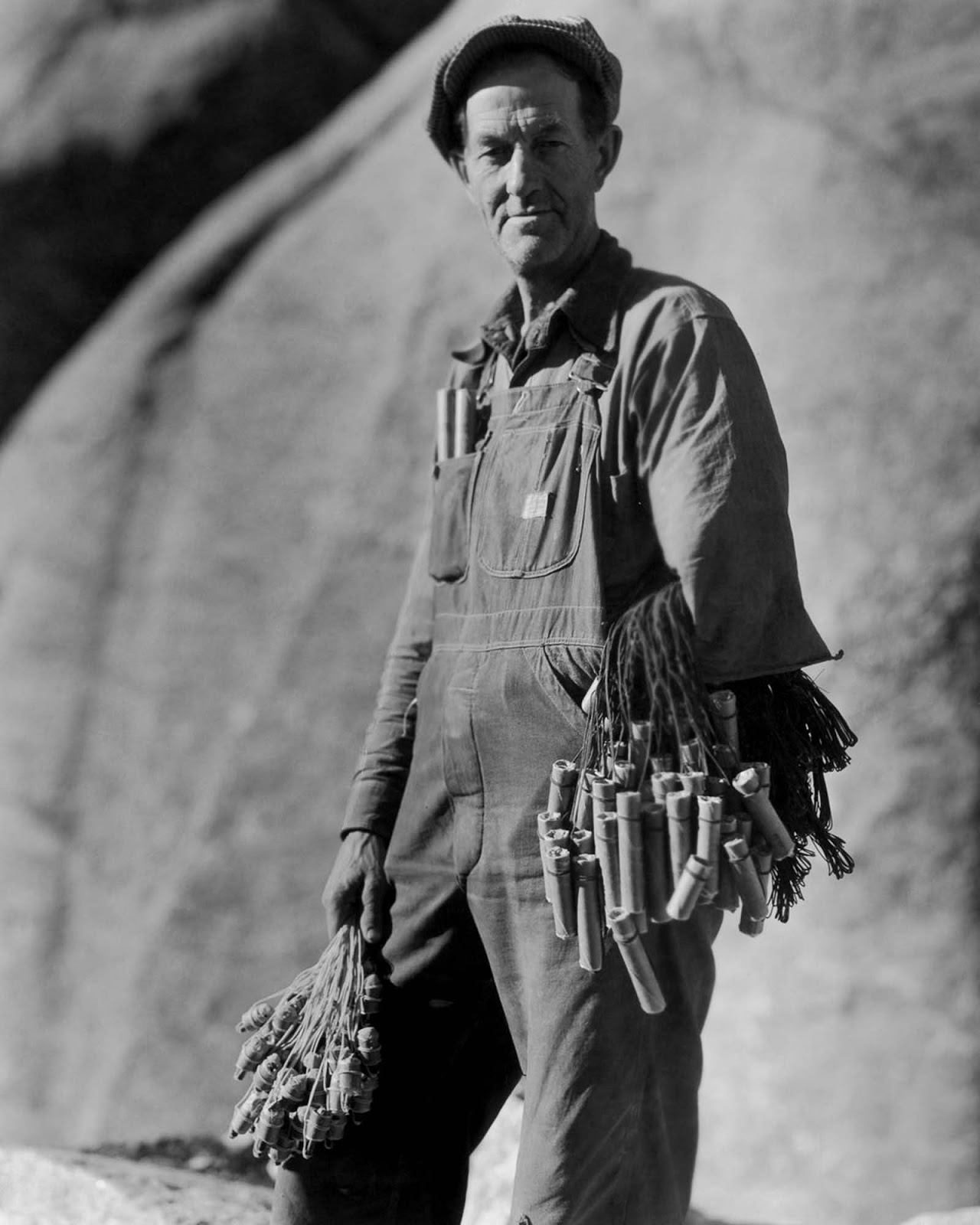

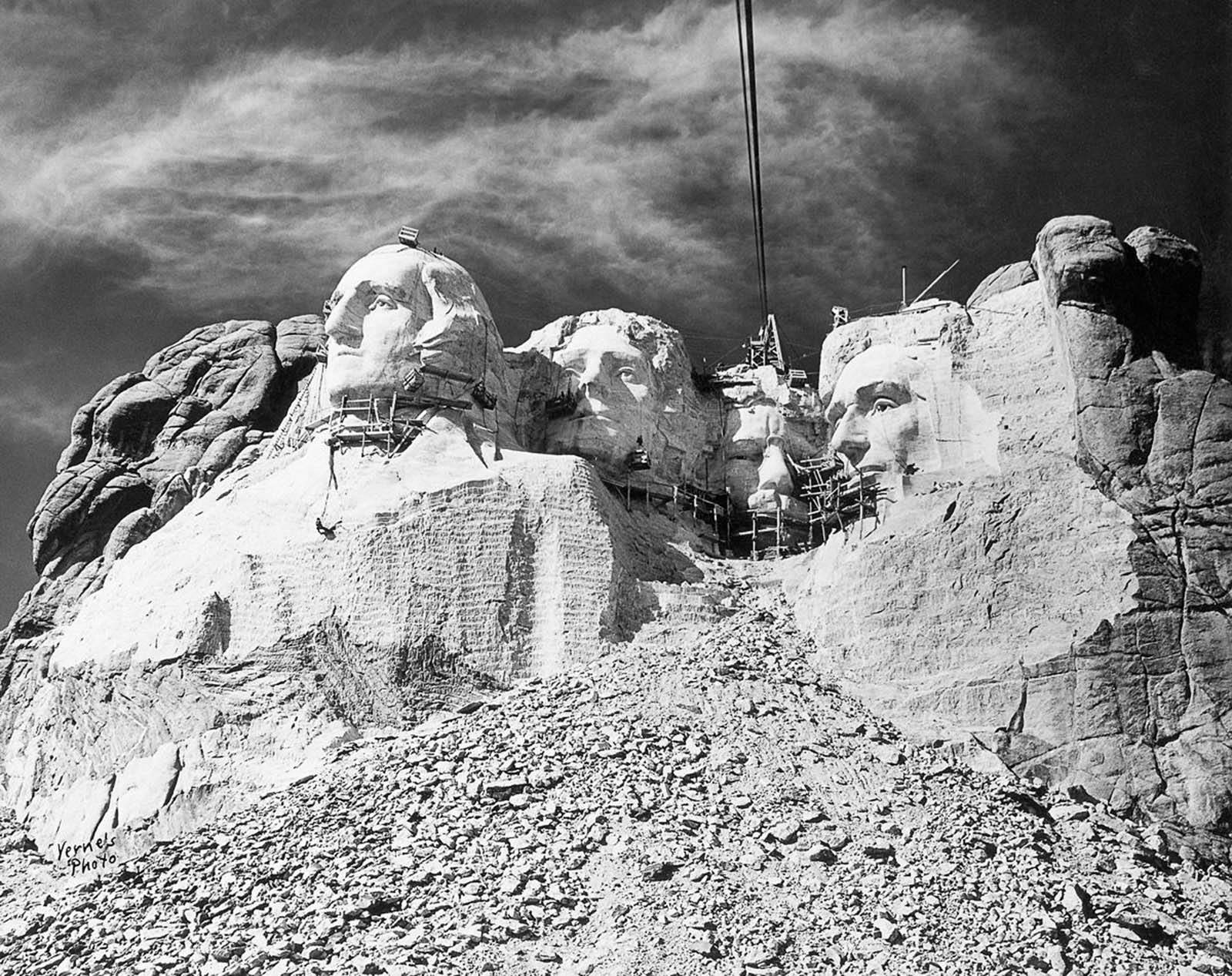

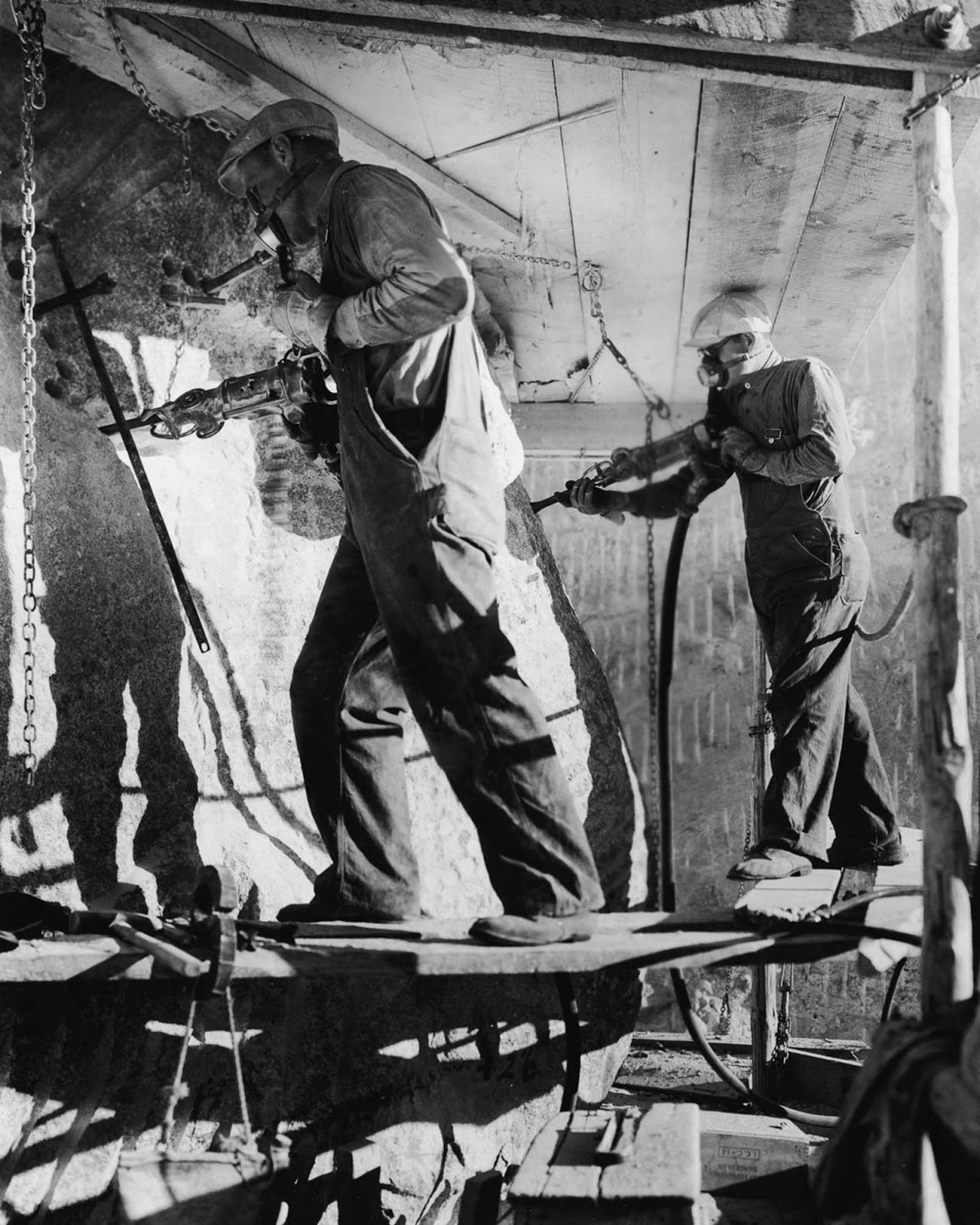

However, American sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who was hired to design and execute the project, rejected that site because the rock there was too eroded and unstable and instead chose nearby Mount Rushmore with its solid granite rock face. Borglum also proposed that the four heads in the sculpture symbolize the first 150 years of the United States: Washington to represent the country’s founding; Jefferson, its expansion across the continent; Roosevelt, its development domestically and as a global power; and Lincoln, its preservation through the ordeal of civil war. Between October 4, 1927, and October 31, 1941, Gutzon Borglum and 400 workers sculpted the colossal 60-foot-high (18 m) carvings of United States Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln Progress was hampered by periodic funding shortfalls, design issues (the likeness of Jefferson, originally on Washington’s right side, had to be redone on the other side), and the death of Borglum in March 1941, several months before the sculpture was finished. Borglum’s son, Lincoln, took over the final work on the project, which was completed in October 1941. In all, the work consisted of six and a half years of actual carving by hundreds of workers, who used dynamite, jackhammers, chisels, and drills to shape the massive stone sculpture assemblage. Borglum’s technique involved blasting away much of the rock with explosives, drilling a large number of closely spaced holes, and then chipping the remaining rock away until the surface was smooth. Much of the 450,000 tons of rock removed in the process was left in a heap at the base of the memorial. The federal government paid most of the nearly $1 million cost, with much of the remainder coming from private donations. Washington’s head was dedicated in 1930, Jefferson’s in 1936, Lincoln’s in 1937, and Roosevelt’s in 1939. Mount Rushmore was constructed with the intention of symbolizing “the triumph of modern society and democracy”, for the latest Indigenous occupants. However, for the Lakota Sioux the monument embodies a story of “struggle and desecration”. The U.S. Government promised the Sioux territory, including the entirety of the Black Hills, in the Treaty of 1868. That lasted only until the discovery of gold on the land, and soon after white settlers migrated to the area in the 1870s. The federal government then forced the Sioux to relinquish the Black Hills portion of their reservation. The battle that took place in 1890 between the US Army and the Native Americans is known as the Wounded Knee Massacre, “where hundreds of unarmed Sioux women, children, and men were shot and killed by U.S. troops”, as summarized by PBS regarding historian Dee Brown’s account of the event. The 1980 United States Supreme Court decision United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians ruled that the Sioux had not received just compensation for their land in the Black Hills, which includes Mount Rushmore. The memorial is now among the most heavily visited NPS properties and is one of the top tourist attractions in the country. Over the years, components of the site’s infrastructure, such as accessibility and visitor facilities and services, have been improved and expanded to accommodate the two million or more people who go there annually. Among these is the Avenue of Flags (opened 1976), a walkway leading toward the mountain that is flanked on both sides by flags of the country’s 56 states and territories. Another major renovation, completed in 1998, added the Grand View Terrace and its amphitheater, affording vistas of the monument at the north (mountainside) end of the Avenue of Flags. Also, the Presidential Trail, which provides the closest views of the sculpture; and the Lincoln Borglum Museum, which has exhibits on the memorial’s history. The Sculptor’s Studio (1939) displays tools used in the carving and the scale model used to create the sculpture. (Photo credit: Library of Congress / Archive Photos / Getty Images / Britannica Encyclopedia). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe