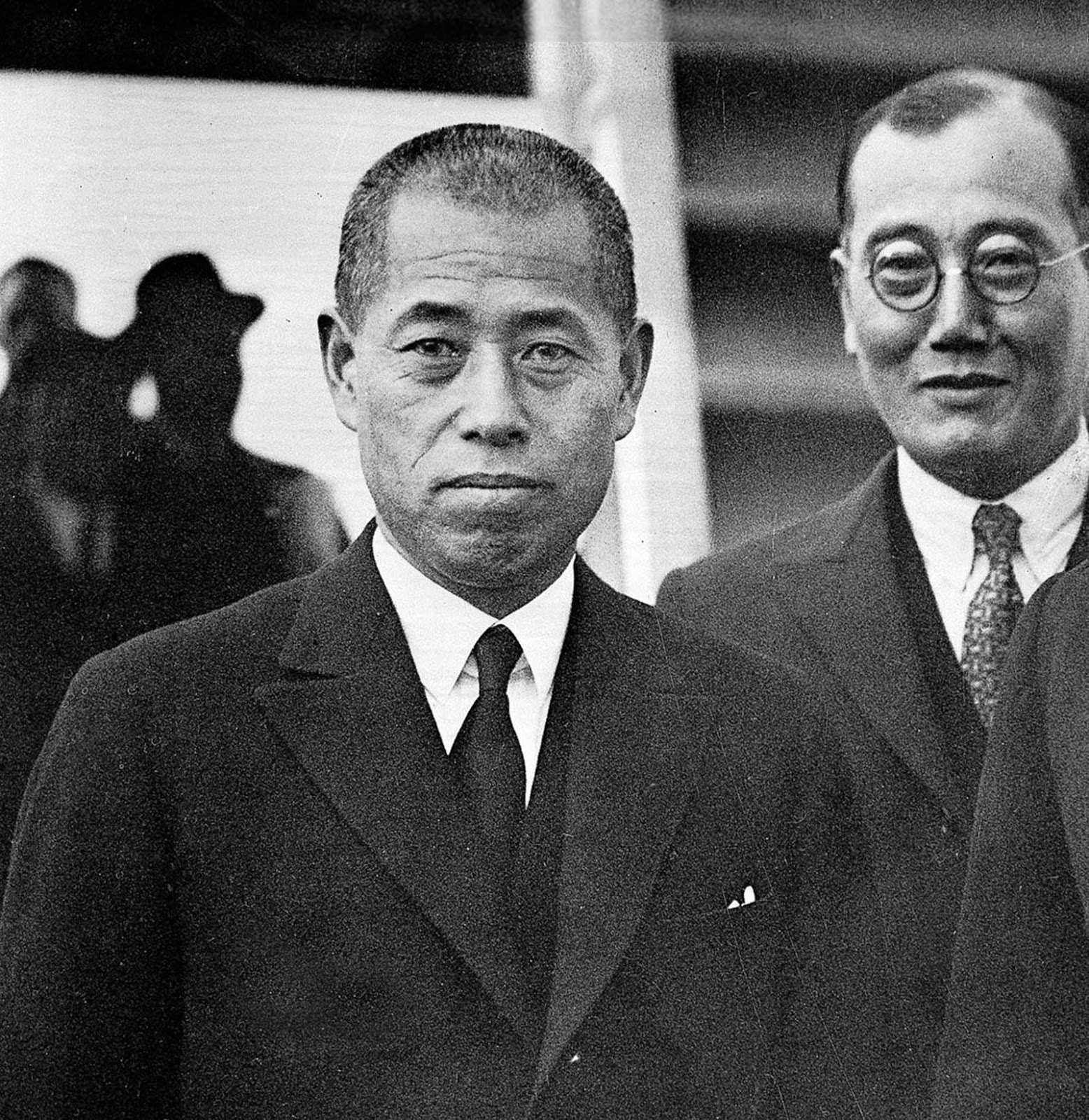

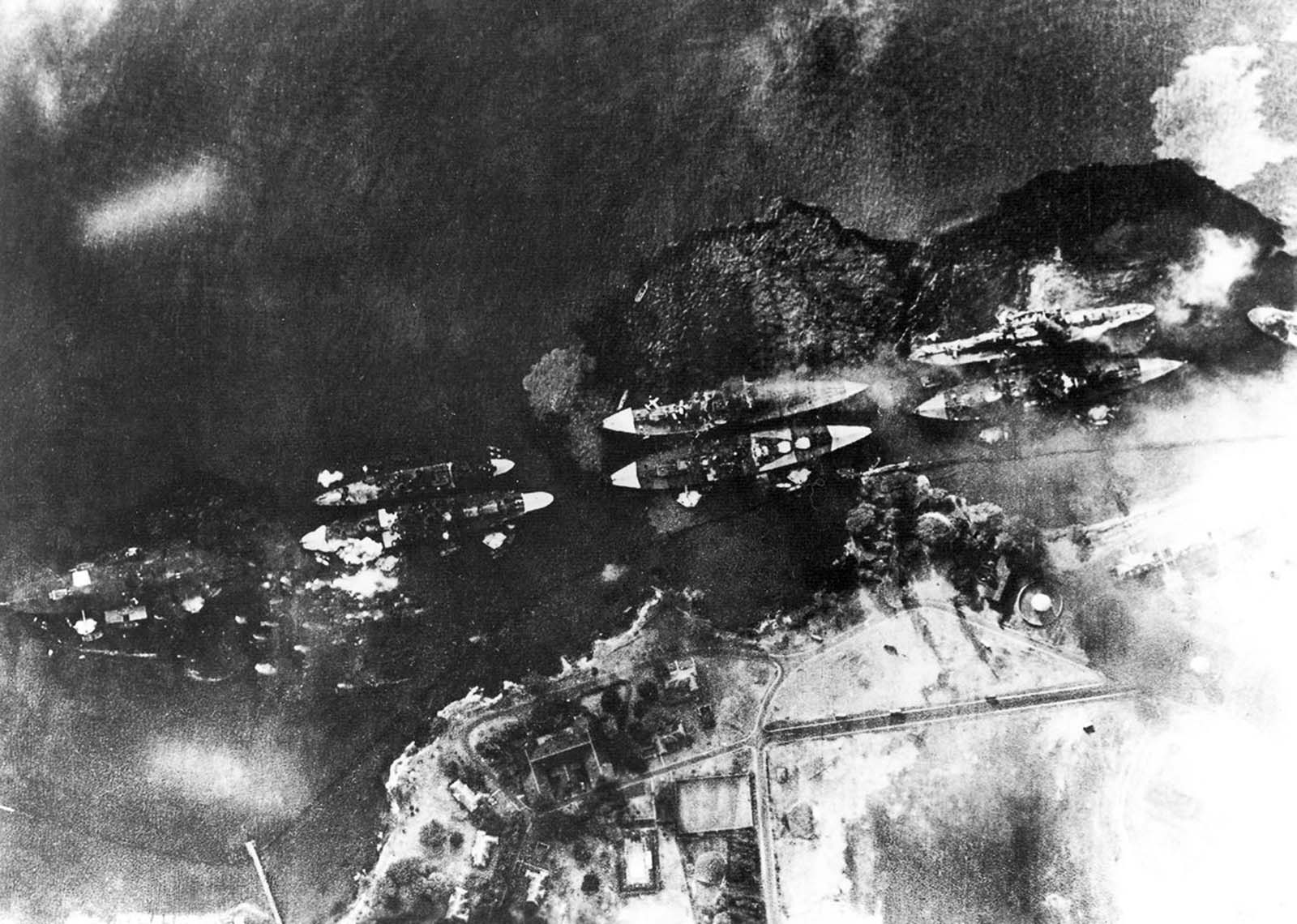

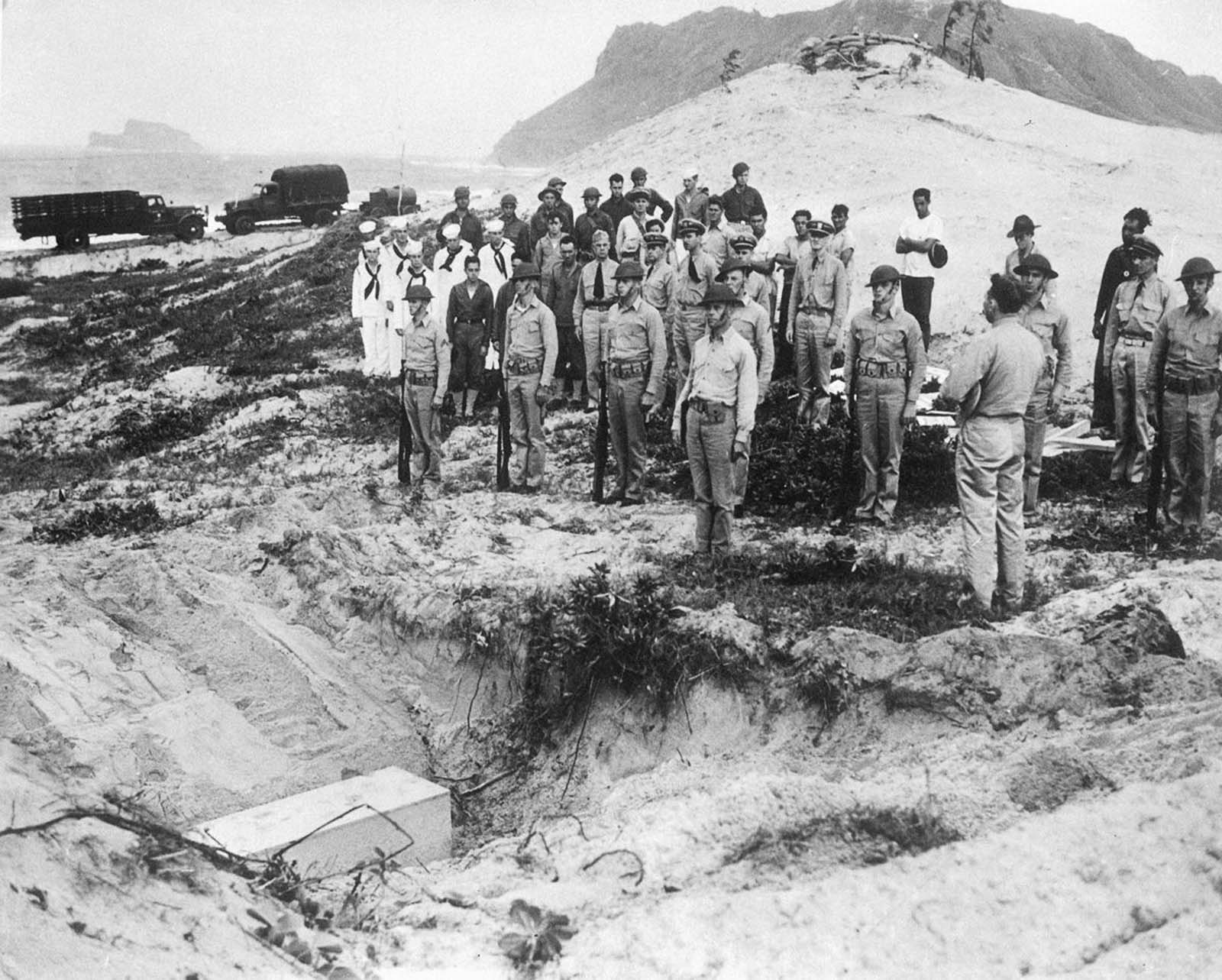

He had also traveled and studied throughout the United States and understood that Japan’s island empire could not hope to defeat the Americans’ vast resources and industrial capacity in a prolonged war. Ironically, though Yamamoto laid out the plan to strike Pearl Harbor, he also happened to be one of its most vocal opponents. Yamamoto knew the risks of attacking Pearl Harbor, not just to the fleet flying into Hawaiian airspace, but also to the overall Japanese ambitions. While those in favor of the attack believed it would keep the United States at bay, Yamamoto feared—correctly, as it turned out—it would simply enrage the nation and draw it into a war Japan couldn’t win. While Yamamoto was vocally opposed to the Pearl Harbor attack, he was up against more powerful men who ultimately decided to go forward with the attack. The Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff Chief Osami Nagano rejected Yamamoto’s concerns, arguing that negotiations with the United States were a waste of time. Supported by Minister of War General Hideki Tojo, Nagano spoke often about necessary military action against the nations that stood in their way in the Pacific, including the United States and European allies with colonies in Southeast Asia. Both Nagano and Tojo feared giving in to demands laid out in negotiations with the United States would reverse Japanese advances made during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Above all, the proud nation feared a loss of face and morale. The more Yamamoto expressed concern for the outcome of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the more unwavering Nagano became in his belief that it was necessary, and was Japan’s only possible course of action. By November 3rd, 1941, a month before the attack was launched, Nagano presented the attack plan to Emperor Hirohito for final approval. Two days later, the emperor announced his approval at the Imperial Conference, decreeing a December start date should negotiations with the US fall through. On Nov. 26, a naval group unlike any ever assembled set out from Japan and began sneaking across the North Pacific. The secret fleet included nine destroyers, two battleships, three cruisers, three submarines, seven fuel tankers — and six aircraft carriers laden with more than 400 planes, the greatest aerial attack force ever launched from the sea. Many in the fleet feared that the two-week crossing would be impossible to execute without alerting the Americans, potentially turning their surprise attack into a disastrous trap. To avoid detection, the carrier task force observed radio silence and followed a northerly path to Hawaii, a route that was little traveled and subject to winter storms, which thwarted aerial reconnaissance. Yet when the ships reached position 230 miles north of Oahu in the early hours of Dec. 7, they remained undetected. Japanese subs lurking outside the mouth of Pearl Harbor on the south side of the island deployed five two-man midget submarines into the harbor. At 6:00 a.m., the first wave of 183 fighters and bombers began spinning up and taking off. At 7:40 a.m., the leader of the first wave, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, spotted the military installations at Pearl Harbor. Seeing no activity, he gave the order to attack and then transmitted the codewords “Tora! Tora! Tora!” back to the fleet — the signal that total surprise had been achieved. Torpedo bombers angled in and dropped specially-modified torpedoes which raced through the shallow harbor and punctured the hulls of the ships anchored on Battleship Row. The USS Arizona was struck by a bomb near its ammunition magazines, causing a cataclysmic blast that killed nearly 1,200 sailors. Despite the utter surprise, the Americans began to organize and return fire in minutes, filling the skies with anti-aircraft flak and small-arms fire by the time the second wave of 171 planes arrived at 9:00 a.m. At 9:45 a.m., just two hours after the start of the attack, it was over. The Japanese pilots returned to their carriers and sailed away in triumph. 2,403 American service members and civilians had been killed. The Japanese had successfully sunk or damaged 19 ships, destroyed 188 aircraft, and damaged many more, with only 29 aircraft shot down, 64 men killed and one submarine crewman captured. Ultimately, however, the attack failed in its strategic goals. Though it was a stunning blow, the Japanese failed to take out fuel depots, dry docks, and other facilities which were critical to the American war effort. The loss of a few battleships would prove less consequential than expected in a conflict increasingly fought from the decks of aircraft carriers many miles apart. Rather than cow the Americans into submission, the attack — which came before any official declaration of war — had them howling for revenge and uninterested in negotiations. When Yamamoto, the architect of the raid, learned that the declaration of war had not been delivered until after the attack, he is rumored to have said, “I fear all we have done today is to awaken a great sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.” (Photo credit: AP / US Navy National Museum of Aviation / Hulton Archive / Getty Images / Library of Congress). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe