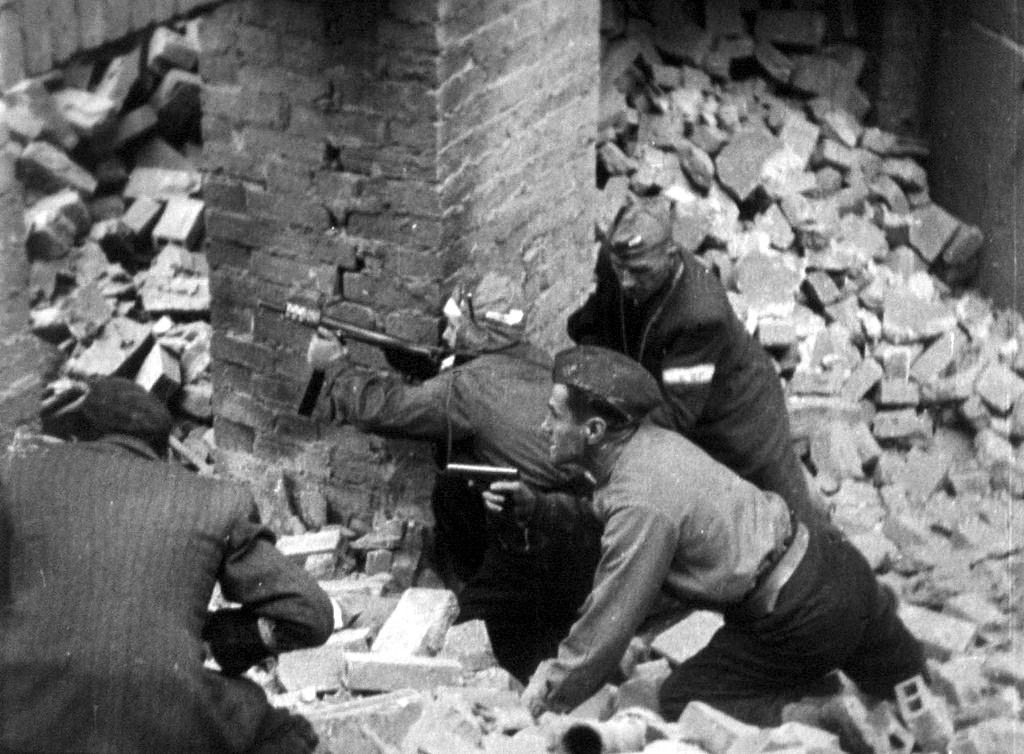

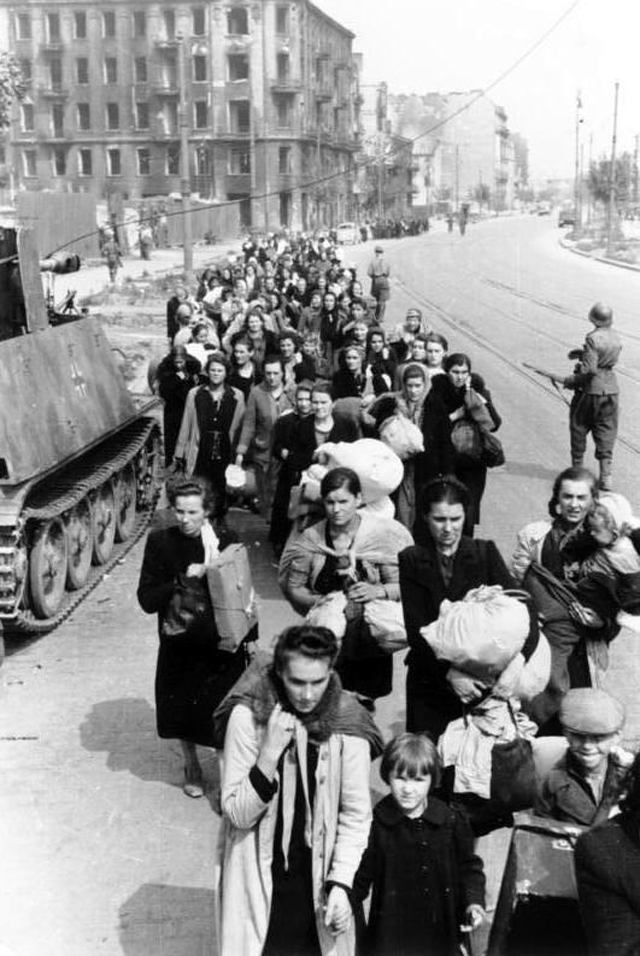

The Uprising began on 1 August 1944 as part of a nationwide Operation Tempest, launched at the time of the Soviet Lublin–Brest Offensive. The main Polish objectives were to drive the Germans out of Warsaw while helping the Allies defeat Germany. An additional, political goal of the Polish Underground State was to liberate Poland’s capital and assert Polish sovereignty before the Soviet-backed Polish Committee of National Liberation could assume control. Other immediate causes included a threat of mass German round-ups of able-bodied Poles for “evacuation”; calls by Radio Moscow’s Polish Service for uprising; and an emotional Polish desire for justice and revenge against the enemy after five years of German occupation. Initially, the Poles established control over most of central Warsaw, but the Soviets ignored Polish attempts to make radio contact with them and did not advance beyond the city limits. Intense street fighting between the Germans and Poles continued. By 14 September, the eastern bank of the Vistula River opposite the Polish resistance positions was taken over by the Polish troops fighting under the Soviet command; 1,200 men made it across the river, but they were not reinforced by the Red Army. This, and the lack of air support from the Soviet air base five-minutes flying time away, led to allegations that Joseph Stalin tactically halted his forces to let the operation fail and allow the Polish resistance to be crushed. Arthur Koestler called the Soviet attitude “one of the major infamies of this war which will rank for the future historian on the same ethical level with Lidice.” On the other hand, David Glantz argued that the uprising started too early and the Red Army could not realistically have aided it, regardless of Soviet intentions. Winston Churchill pleaded with Stalin and Franklin D. Roosevelt to help Britain’s Polish allies, to no avail. Then, without Soviet air clearance, Churchill sent over 200 low-level supply drops by the Royal Air Force, the South African Air Force, and the Polish Air Force under British High Command, in an operation known as the Warsaw Airlift. Later, after gaining Soviet air clearance, the U.S. Army Air Force sent one high-level mass airdrop as part of Operation Frantic, although 80% of these supplies landed in German-controlled territory. Although the exact number of casualties is unknown, it is estimated that about 16,000 members of the Polish resistance were killed and about 6,000 badly wounded. In addition, between 150,000 and 200,000 Polish civilians died, mostly from mass executions. Jews being harboured by Poles were exposed by German house-to-house clearances and mass evictions of entire neighbourhoods. German casualties totalled over 2,000 to 17,000 soldiers killed and missing. During the urban combat, approximately 25% of Warsaw’s buildings were destroyed. Following the surrender of Polish forces, German troops systematically levelled another 35% of the city block by block. Together with earlier damage suffered in the 1939 invasion of Poland and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, over 85% of the city was destroyed by January 1945 when the course of the events on the Eastern Front forced the Germans to abandon the city.

Life behind the lines

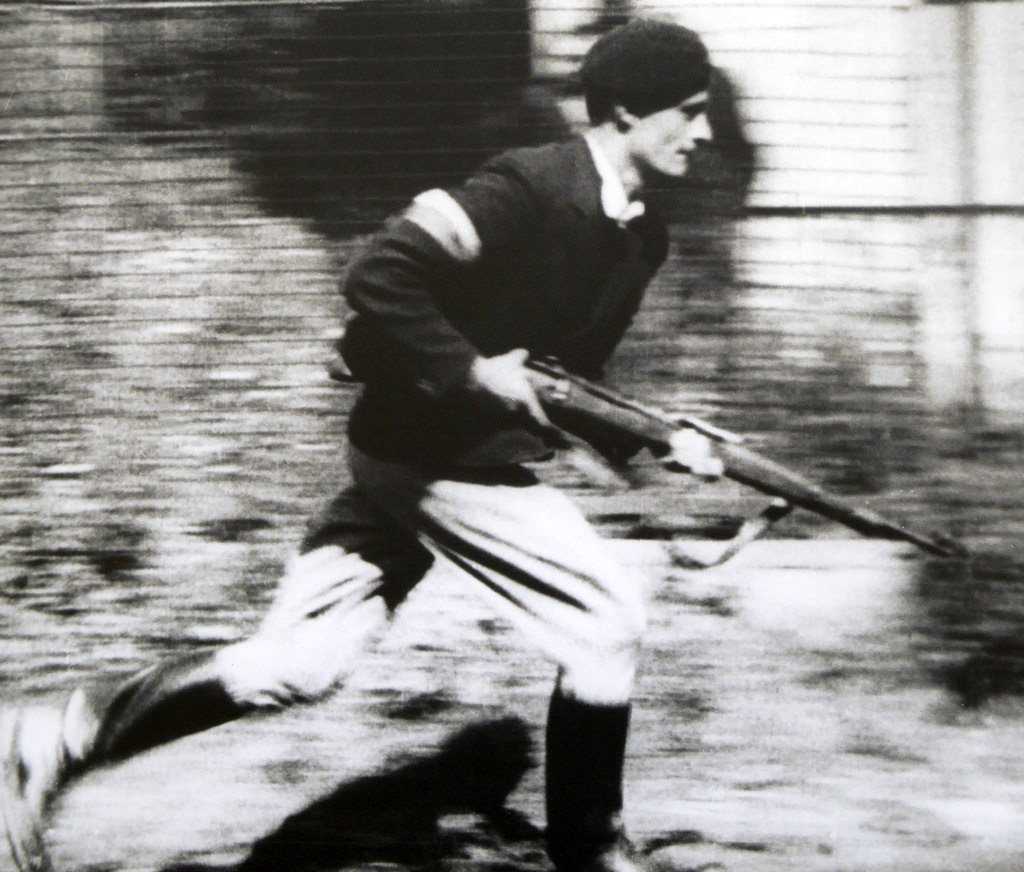

In 1939 Warsaw had roughly 1,350,000 inhabitants. Over a million were still living in the city at the start of the Uprising. In Polish-controlled territory, during the first weeks of the Uprising, people tried to recreate the normal day-to-day life of their free country. Cultural life was vibrant, both among the soldiers and civilian population, with theatres, post offices, newspapers and similar activities. Boys and girls of the Polish Scouts acted as couriers for an underground postal service, risking their lives daily to transmit any information that might help their people. Near the end of the Uprising, lack of food and medicine, overcrowding and indiscriminate German air and artillery assault on the city made the civilian situation more and more desperate. Booby traps, such as thermite-laced candy pieces, may have also been used in German-controlled districts of Warsaw; targeting Polish youth.

Food shortages

As the Uprising was supposed to be relieved by the Soviets in a matter of days, the Polish underground did not predict food shortages would be a problem. However, as the fighting dragged on, the inhabitants of the city faced hunger and starvation. A major breakthrough took place on 6 August, when Polish units recaptured the Haberbusch i Schiele brewery complex at Ceglana Street. From that time on the citizens of Warsaw lived mostly on barley from the brewery’s warehouses. Every day up to several thousand people organized into cargo teams reported to the brewery for bags of barley and then distributed them in the city centre. The barley was then ground in coffee grinders and boiled with water to form a so-called spit-soup. The “Sowiński” Battalion managed to hold the brewery until the end of the fighting. Another serious problem for civilians and soldiers alike was a shortage of water. By mid-August most of the water conduits were either out of order or filled with corpses. In addition, the main water pumping station remained in German hands. To prevent the spread of epidemics and provide the people with water, the authorities ordered all janitors to supervise the construction of water wells in the backyards of every house. On 21 September the Germans blew up the remaining pumping stations at Koszykowa Street and after that the public wells were the only source of potable water in the besieged city. By the end of September, the city centre had more than 90 functioning wells.

Polish Media

Before the Uprising the Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Home Army had set up a group of war correspondents. Headed by Antoni Bohdziewicz, the group made three newsreels and over 30,000 meters of film tape documenting the struggles. The first newsreel was shown to the public on 13 August in the Palladium cinema at Złota Street. In addition to films, dozens of newspapers appeared from the very first days of the uprising. Several previously underground newspapers started to be distributed openly. The two main daily newspapers were the government-run Rzeczpospolita Polska and military Biuletyn Informacyjny. There were also several dozen newspapers, magazines, bulletins and weeklies published routinely by various organizations and military units. The Błyskawica long-range radio transmitter, assembled on 7 August in the city centre, was run by the military, but was also used by the recreated Polish Radio from 9 August. It was on the air three or four times a day, broadcasting news programmes and appeals for help in Polish, English, German and French, as well as reports from the government, patriotic poems and music. It was the only such radio station in German-held Europe. Among the speakers appearing on the resistance radio were Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, Zbigniew Świętochowski, Stefan Sojecki, Jeremi Przybora, and John Ward, a war correspondent for The Times of London.

After the war

Most soldiers of the Home Army (including those who took part in the Warsaw Uprising) were persecuted after the war; captured by the NKVD or UB political police. They were interrogated and imprisoned on various charges, such as that of fascism. Many of them were sent to Gulags, executed or disappeared. Between 1944 and 1956, all of the former members of Battalion Zośka were incarcerated in Soviet prisons. In March 1945, a staged trial of 16 leaders of the Polish Underground State held by the Soviet Union took place in Moscow – (the Trial of the Sixteen). The Government Delegate, together with most members of the Council of National Unity and the C-i-C of the Armia Krajowa, were invited by Soviet general Ivan Serov with agreement of Joseph Stalin to a conference on their eventual entry to the Soviet-backed Provisional Government. They were presented with a warrant of safety, yet they were arrested in Pruszków by the NKVD on 27 and 28 March. Leopold Okulicki, Jan Stanisław Jankowski and Kazimierz Pużak were arrested on the 27th with 12 more the next day. A. Zwierzynski had been arrested earlier. They were brought to Moscow for interrogation in the Lubyanka. After several months of brutal interrogation and torture, they were presented with the forged accusations of collaboration with Nazis and planning a military alliance with Germany . Many resistance fighters, captured by the Germans and sent to POW camps in Germany, were later liberated by British, American and Polish forces and remained in the West. Among those were the leaders of the uprising Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski and Antoni Chruściel. The facts of the Warsaw Uprising were inconvenient to Stalin, and were twisted by propaganda of the People’s Republic of Poland, which stressed the failings of the Home Army and the Polish government-in-exile, and forbade all criticism of the Red Army or the political goals of Soviet strategy. In the immediate post-war period, the very name of the Home Army was censored, and most films and novels covering the 1944 Uprising were either banned or modified so that the name of the Home Army did not appear. From the 1950s on, Polish propaganda depicted the soldiers of the Uprising as brave, but the officers as treacherous, reactionary and characterized by disregard of the losses. The first publications on the topic taken seriously in the West were not issued until the late 1980s. In Warsaw no monument to the Home Army was built until 1989. Instead, efforts of the Soviet-backed People’s Army were glorified and exaggerated. By contrast, in the West the story of the Polish fight for Warsaw was told as a tale of valiant heroes fighting against a cruel and ruthless enemy. It was suggested that Stalin benefited from Soviet non-involvement, as opposition to eventual Soviet control of Poland was effectively eliminated when the Nazis destroyed the partisans. The belief that the Uprising failed because of deliberate procrastination by the Soviet Union contributed to anti-Soviet sentiment in Poland. Memories of the Uprising helped to inspire the Polish labour movement Solidarity, which led a peaceful opposition movement against the Communist government during the 1980s. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Britannica / Google Arts & Culture / Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe