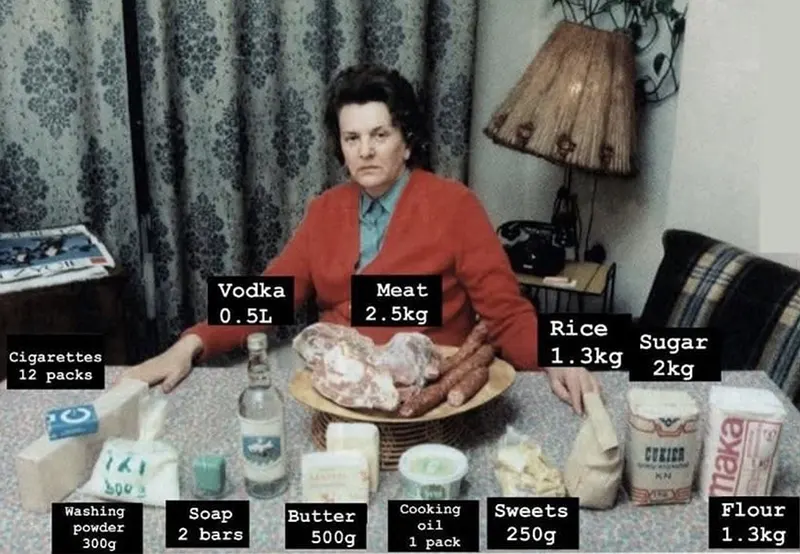

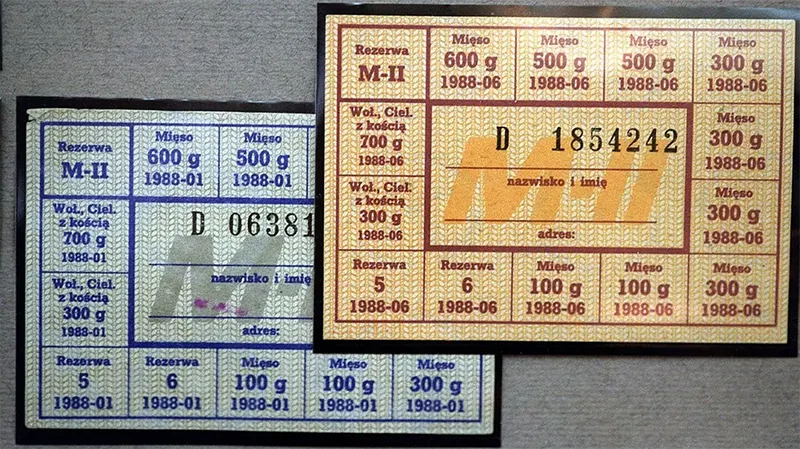

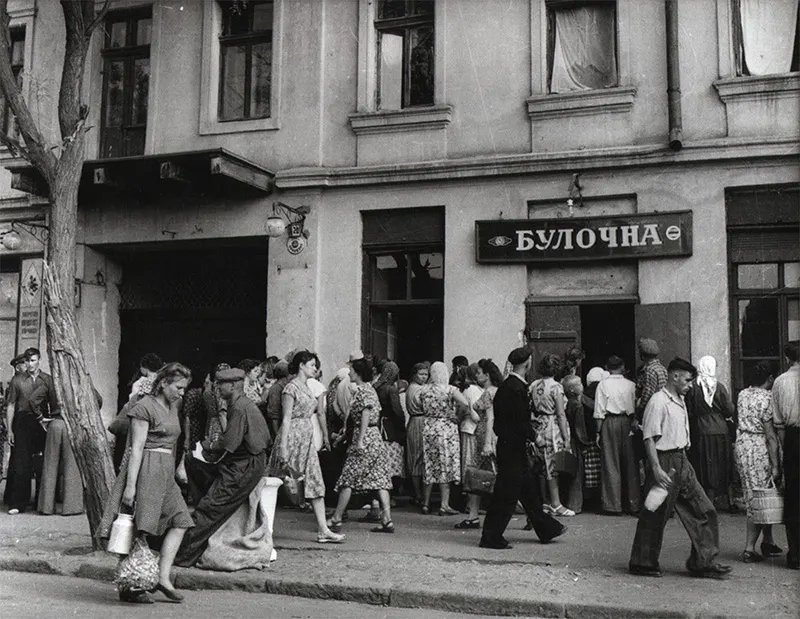

This seemingly modest assortment of goods, meticulously allocated through a complex system of distribution, belies the profound challenges that defined life in communist Poland during that era. Each item, from the staple grains to the precious drops of cooking oil, carries within it the weight of an economic system strained to its limits and a society that defied adversity with unwavering determination. This tableau offers a glimpse into a bygone era when rationing was more than a bureaucratic practice – it became a defining thread in the intricate tapestry of daily existence, shaping the experiences and aspirations of an entire nation. As the 1980s dawned, communist Poland found itself ensnared in the throes of an economic crisis. The central planning system, while intended to ensure equitable distribution, was riddled with inefficiencies and mismanagement. Spiraling foreign debt, obsolete industrial infrastructure, and rampant resource misallocation culminated in a dire scarcity of essential goods that reverberated throughout every facet of society. In response to the burgeoning shortages, the Polish government instituted a rationing mechanism to regulate the distribution of vital commodities. Ration cards emerged as the emblematic symbol of this system, embodying the government’s attempt to maintain a semblance of order amid the chaos. Citizens were allocated quotas for staples such as bread, meat, sugar, and oil, with each ration card serving as both a lifeline and a reminder of scarcity. The most poignant manifestation of this rationing system was observed in the realm of food. Bread, the quintessential staple, became emblematic of the challenges that Polish citizens faced. Bread queues, often stretching for hours, became a ubiquitous sight as individuals patiently waited for their share of sustenance. Meat, a luxury for many, was meted out sparingly, forcing consumers to adapt to cuts and types of meat that were hitherto unfamiliar. In mid-1981 thousands of Poles took part in several hunger demonstrations, organized in cities and towns across the country. Banners, held by the protesters, stated among others: “Our children are hungry”, “We stand in lines 24 hours a day”, “We want to split bread, not Poland”, “The hungry of all countries – unite!”, and “We are not going to work hungry”. Most of the participants were women and their children, with men walking on the sides and trying to protect the demonstrators. As Jacek Kuroń later said: “Those crowds wielding banners broke the principle of not leaving factories to take to the streets. They created an atmosphere of such tension that the government probably panicked”. The protests were peaceful, without rioting, and the biggest one took place on 30 July 1981 in Łódź. The situation in Communist Poland was serious enough that it prompted Adam Michnik to write, “Poland faces hunger uprisings”. In April 1981, a regulated sale of meat and meat products was introduced. This complicated rationing system took into account not only the entitled person’s place of work, but also their age, place of residence, and sometimes their health or faith. The introduction of meat rationing opened a “whole new can of worms” as a rumor began circulating that more cards would be introduced for other goods. Thus people began storming stores in order to purchase other types of goods, and this prompted the government to introduce regulated sales. In the following weeks, cards were introduced for many goods, including butter, wheat flour, groats, cereals, rice, washing powder, basic baby items, candies, chocolate, alcohol, cigarettes, soap, cotton pads, milk with a fat content 3.2%, and lard. Regionally or temporarily regulated sales were also enacted for oil, shoes, rugs, citrus fruit, and school supplies (notebooks, drawing blocks, crayons, notebooks, notebooks for cutting, pencils, sharpeners, erasers, plasticine, watercolor paints, brushes). At the beginning of 1982, almost 60 percent of the goods in grocery stores were sold on rationing cards. The “crowning” of these decisions was the introduction of “cards on cards” – a special form on which the cards issued were recorded. It was an attempt to control their spontaneous distribution, and the multiple rations used by conmen. It was relatively late in June 1982, that the fuel ration was officially introduced. In practice, petrol rationing had been carried out before, but it had taken various forms. For some time, its purchase was restricted using a key based on the car’s registration number and calendar. So cars with registration ending in 1 could only fill up on the 1st, 11th, and 21st day of the month, and those with 2 on the 2nd, 12th, and 22nd day, etc. Rationing card regulation was eliminated in the People’s Republic of Poland gradually: in February 1983, the rationing of washing powder and soap was abolished, in April – cigarettes and alcohol, followed by candies. In March 1985, the rationing of flour, cereals and cotton pads ended. In June 1985, the rationing of butter and animal and vegetable fats was over. In November 1985, sugar rationing was abandoned. On 1 June 1986, semolina was removed from the list of rationed goods, and on 1 March 1988, the rationing of chocolate products was ended, and finally, on 1 January 1989, the cards for petrol finally disappeared. At this time, only meat cards remained in circulation. Meat rationing survived until June 1989, which is widely regarded as the symbolic end of the Communist Poland. It was then that Solidarity won the parliamentary elections. Communism fell in Poland with the transformational events that culminated in the Polish Round Table Agreement. These negotiations, involving the Polish United Workers’ Party and the Solidarity movement, marked a pivotal moment in the country’s history. The Round Table Agreement was signed on April 4, 1989, setting the stage for semi-free elections and the eventual dismantling of communist rule. The rationing system gradually eased as the country embarked on its path toward a market-oriented economy. By the early 1990s, following the fall of communism, Poland began to transition away from the rationing system altogether. The ration cards were phased out, and the distribution of goods returned to a more conventional market-based approach. (Photo by Wojtek Laski / Wikimedia Commons / Article based on A ration card for survival – rationing in Communist Poland by Andrzej Zawistowski / Flickr). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe