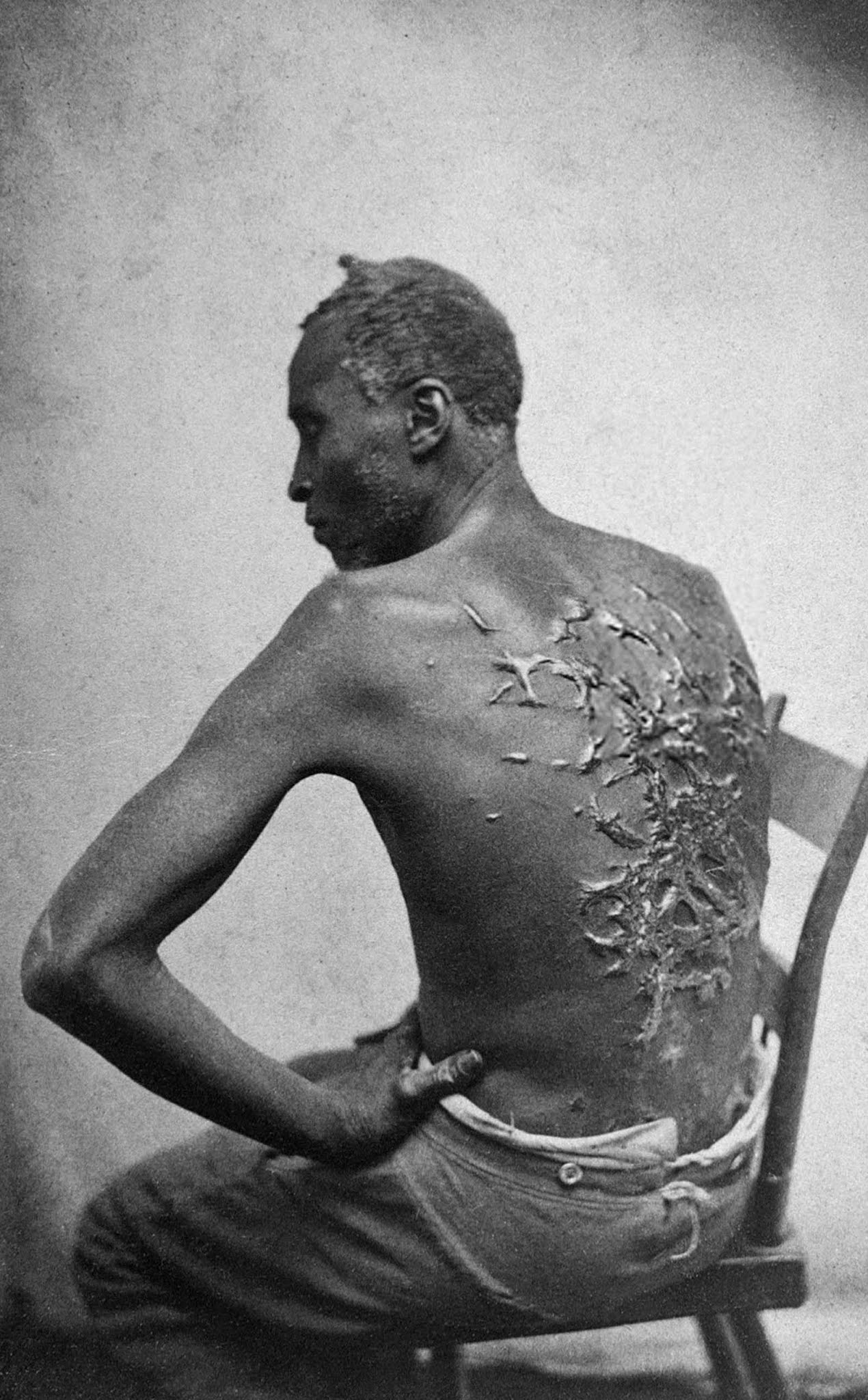

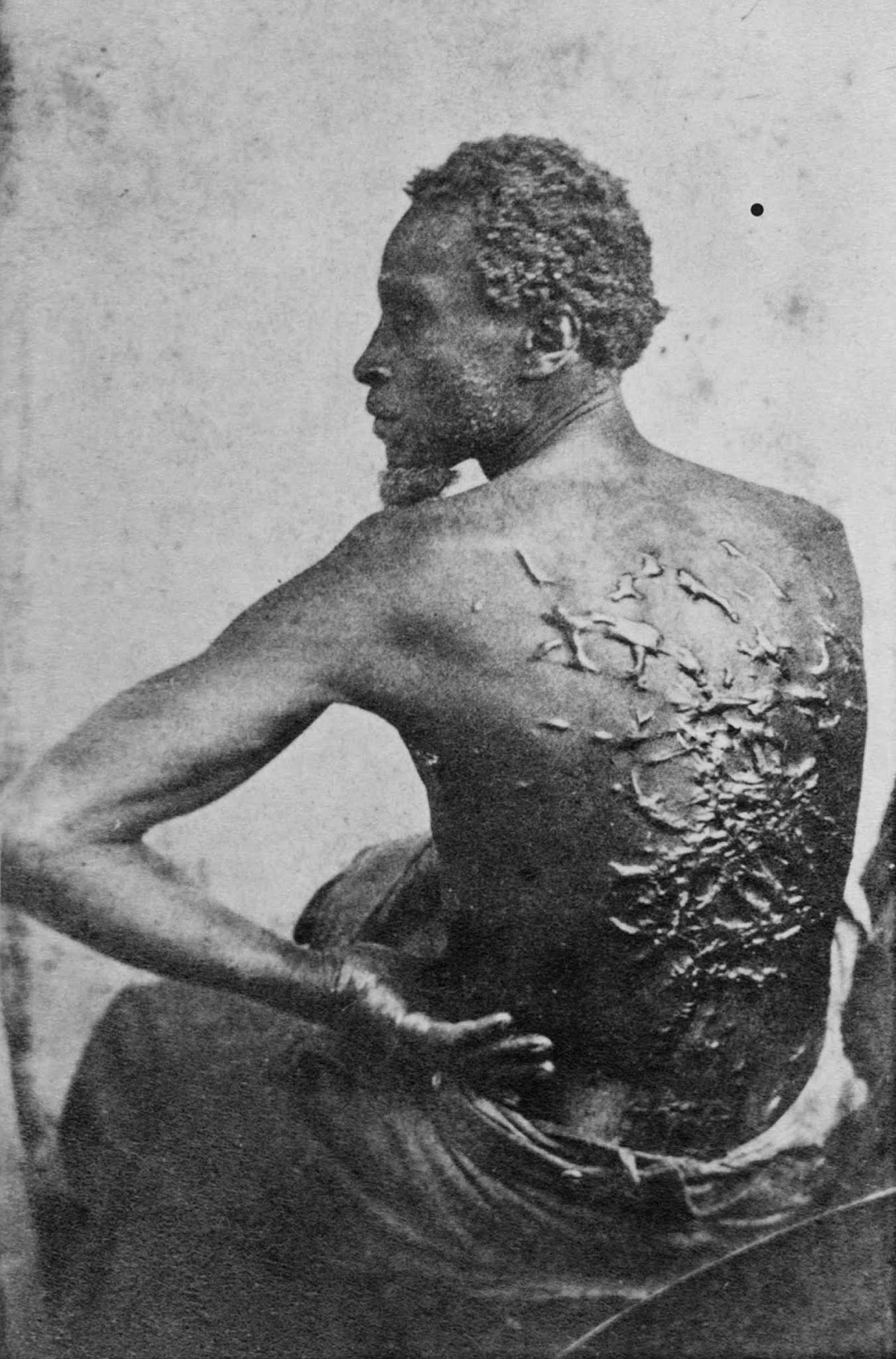

Gordon had received a severe whipping for undisclosed reasons in the fall of 1862. This beating left him with horrible welts on much of the surface of his back. The unusual, but common, way these scars grew outward from the skin is a certain type of scar tissue called “keloid”. It is caused by an excessive protein called collagen within the healing tissue and raises the tissue. People of color are more likely to develop keloid scars. Gordon escaped in March 1863 from the 3,000-acre (12 km2) plantation of John and Bridget Lyons, who held him and nearly 40 other people in slavery at the time of the 1860 census. Upon learning of his flight, his master recruited several neighbors and together they chased after him with a pack of bloodhounds. Gordon had anticipated that he would be pursued and carried with him onions from the plantation, which he rubbed on his body to throw the dogs off-scent. Such resourcefulness worked, and Gordon — his clothes torn and his body covered with mud and dirt — reached the safety of Union soldiers stationed at Baton Rouge ten days later. He had traveled approximately eighty miles. Pherson and his partner Mr. Oliver, who were in camp at the time, produced carte de visite photos of Gordon showing his back. During the examination, Gordon is quoted as saying: “Ten days from to-day I left the plantation. Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping. My master come after I was whipped; he discharged the overseer. My master was not present. I don’t remember the whipping. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping and my sense began to come—I was sort of crazy. I tried to shoot everybody. They said so, I did not know. I did not know that I had attempted to shoot everyone; they told me so. I burned up all my clothes; but I don’t remember that. I never was this way (crazy) before. I don’t know what make me come that way (crazy). My master come after I was whipped; saw me in bed; he discharged the overseer. They told me I attempted to shoot my wife the first one; I did not shoot any one; I did not harm any one. My master’s Capt. JOHN LYON, cotton planter, on Atchafalya, near Washington, Louisiana. Whipped two months before Christmas. The photograph of whipped Gordon’s back became one of the most widely circulated images of slavery of its time, galvanizing public opinion and serving as a wordless indictment of the institution of slavery. Gordon’s disfigured back helped bring the stakes of the Civil War to life, contradicting Southerners’ insistence that their slaveholding was a matter of economic survival, not racism. Gordon joined the Union Army as a guide three months after the Emancipation Proclamation allowed for the enrollment of freed slaves into the military forces. On one expedition, he was taken prisoner by the Confederates; they tied him up, beat him, and left him for dead. He survived and once more escaped to Union lines. Gordon soon afterward enlisted in a U.S. Colored Troops Civil War unit. He was said to have fought bravely as a sergeant in the Corps d’Afrique during the Siege of Port Hudson in May 1863. It was the first time that African-American soldiers played a leading role in an assault. There are no further records indicating what became of Gordon. Yet, this famous image of his whipped back lives on as a powerful testament of slavery’s brutality and the bravery displayed by so many African Americans during this dark period of US history. (Photo credit: William D. McPherson and his partner Mr. Oliver / Library of Congress / Frank H. Goodyear). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe