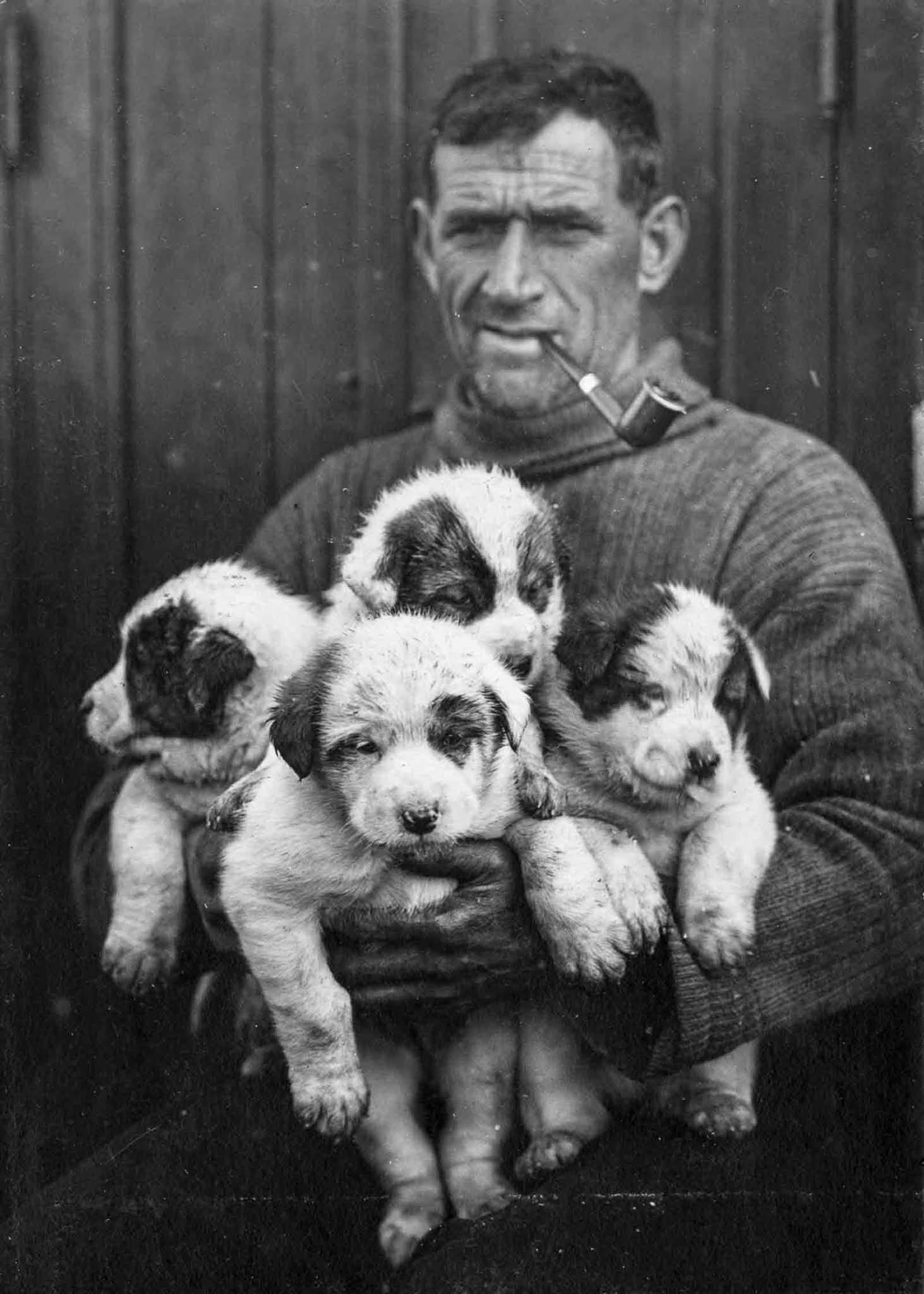

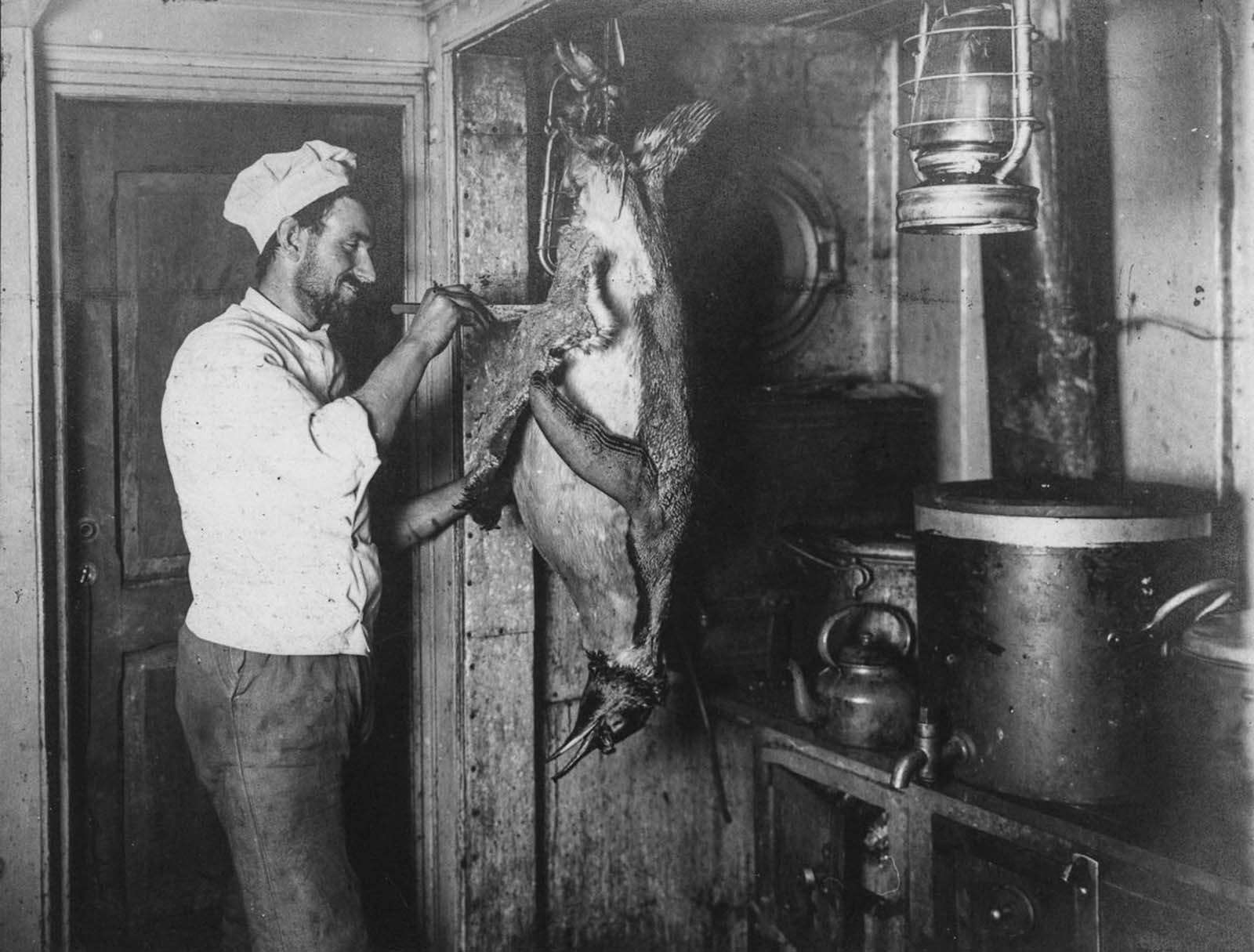

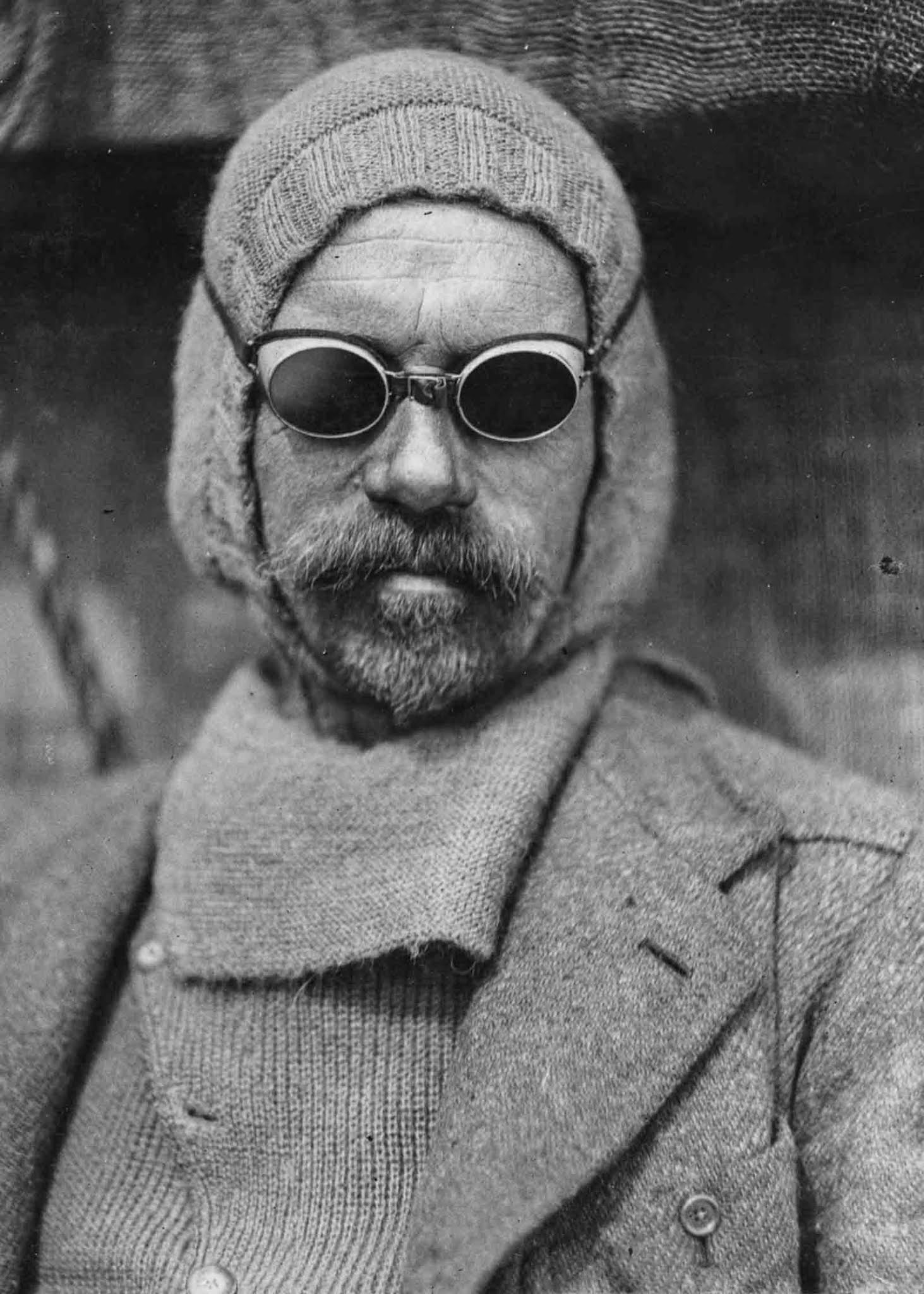

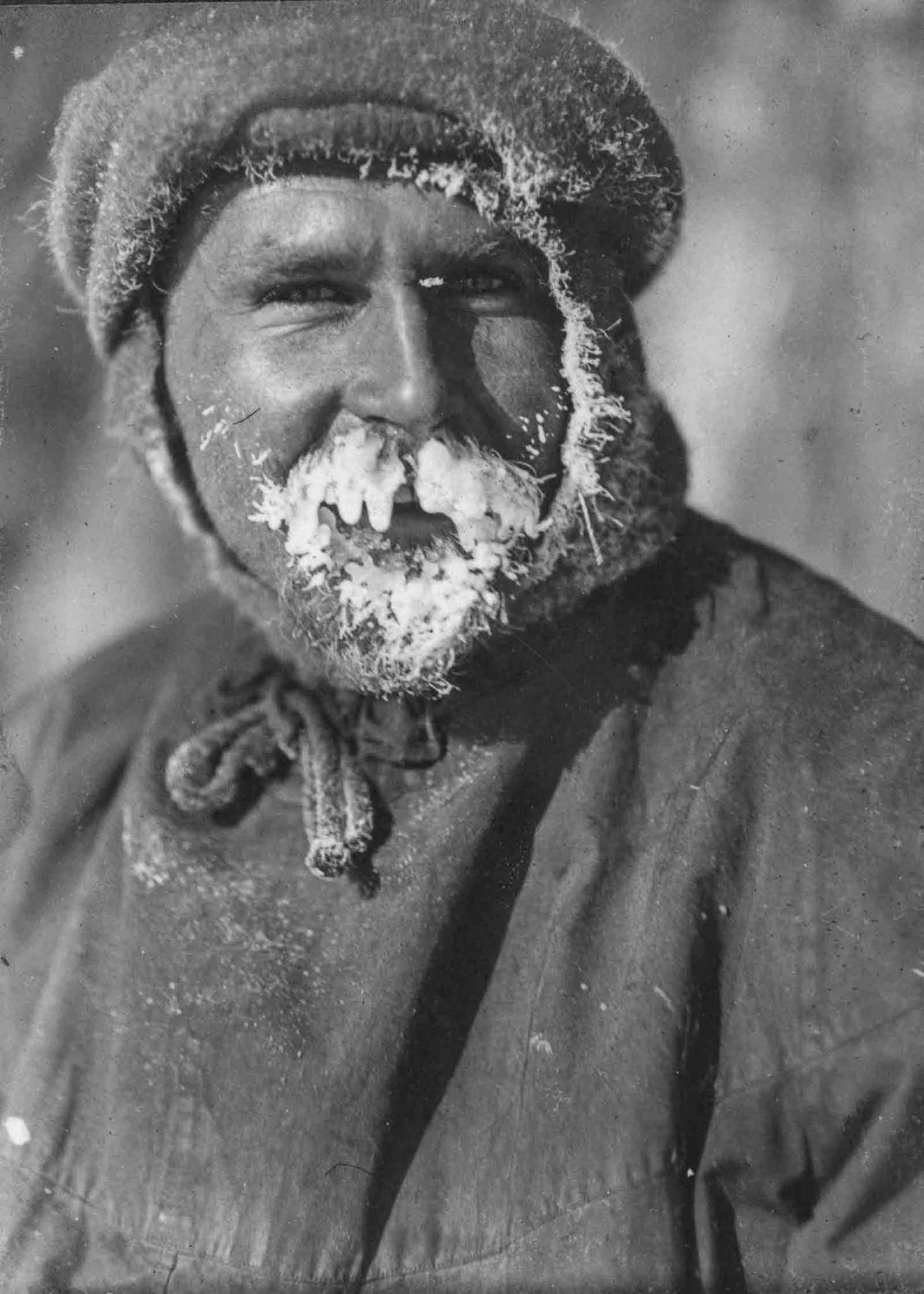

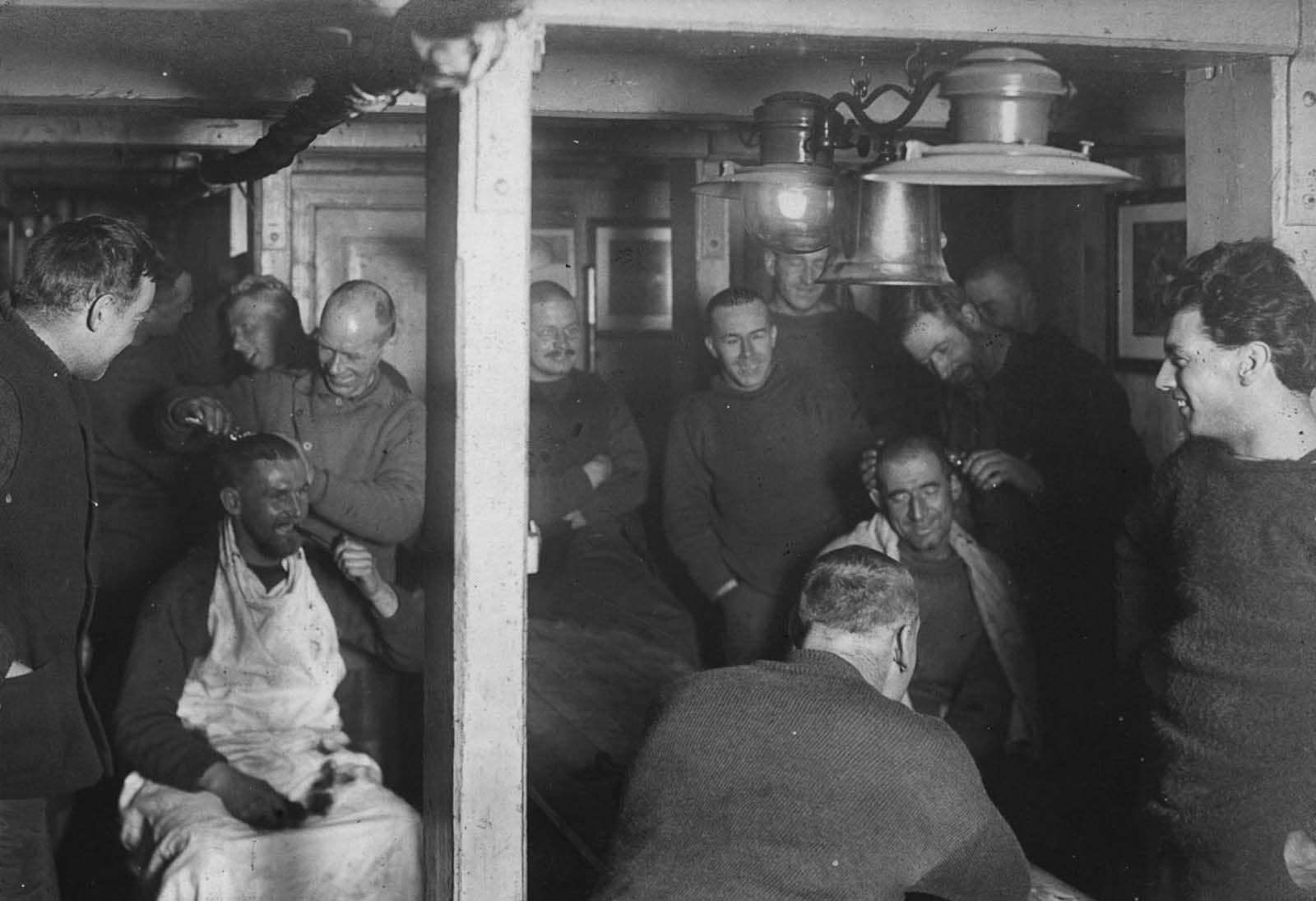

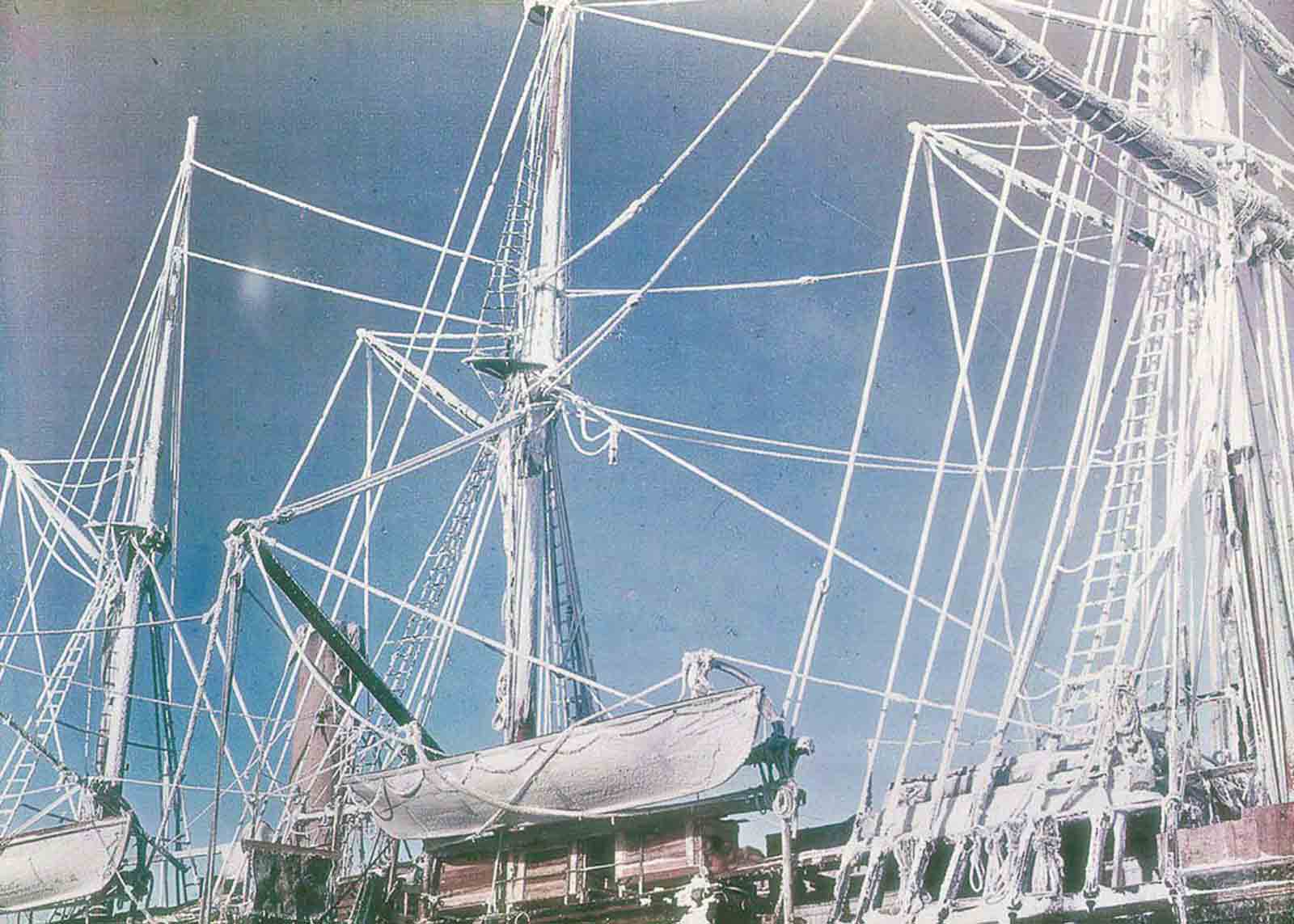

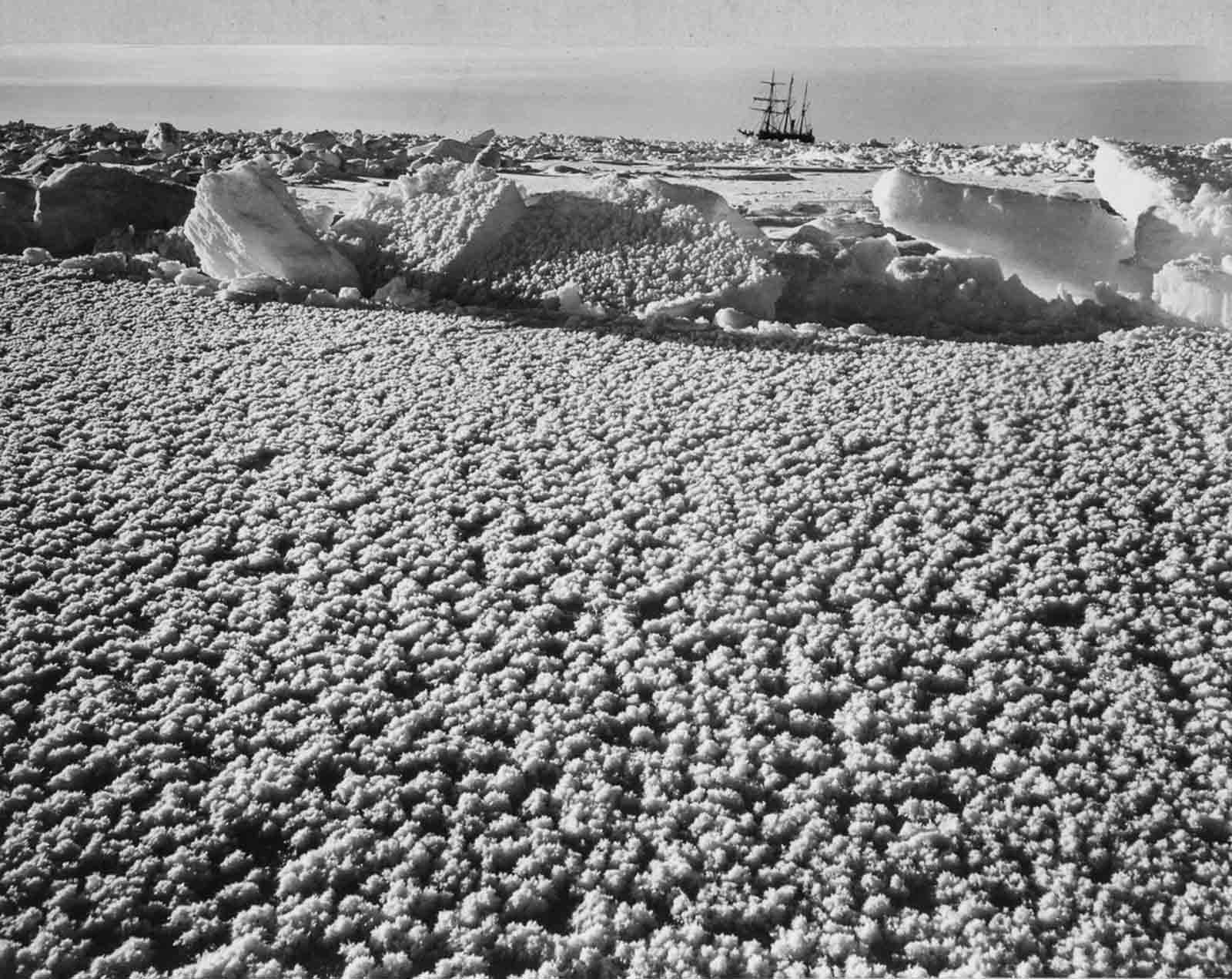

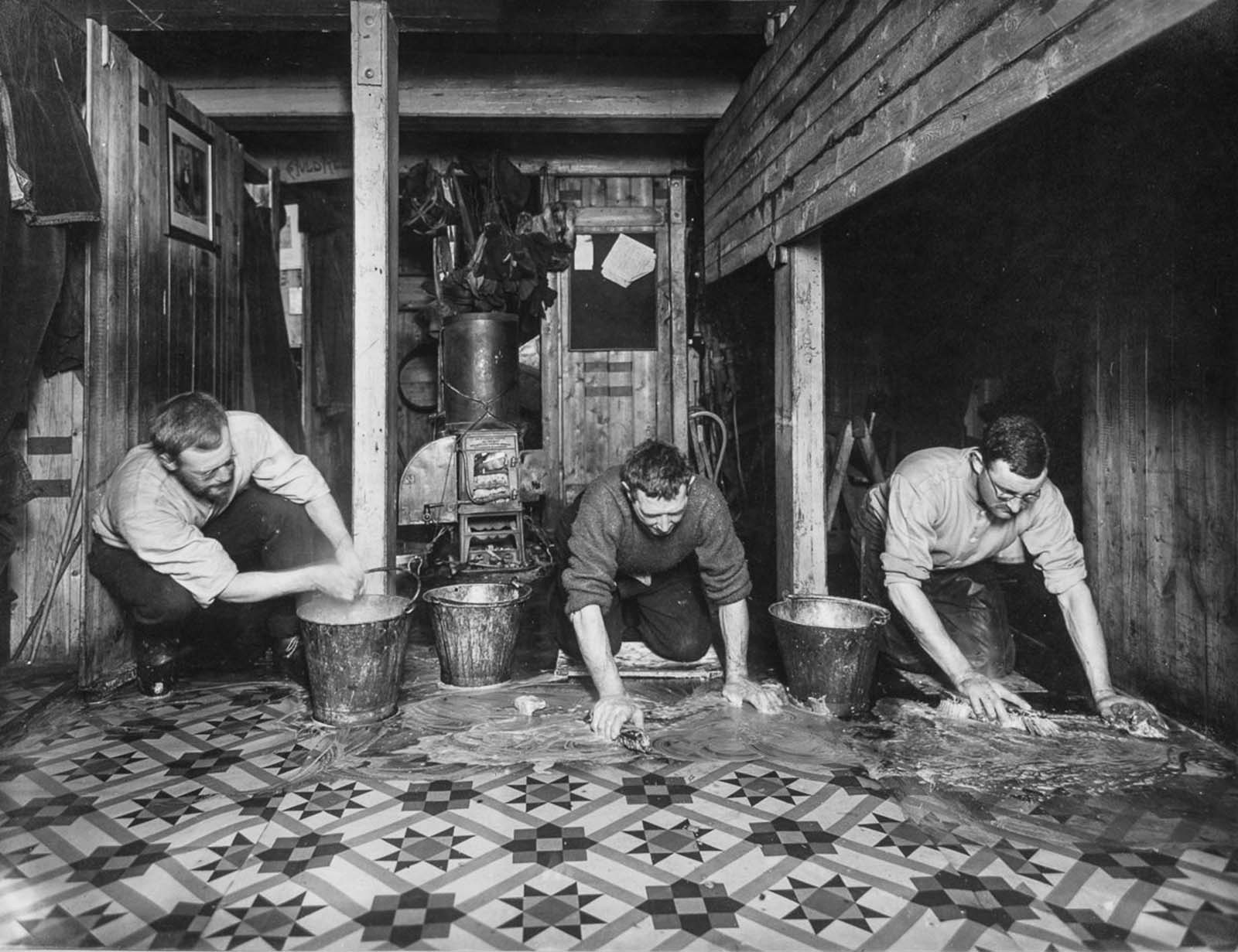

The expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. After Roald Amundsen’s South Pole expedition in 1911, this crossing remained, in Shackleton’s words, the “one great main object of Antarctic journeyings”. Shackleton’s plan was to sail to the Weddell Sea and to land a shore party near Vahsel Bay, in preparation for a transcontinental march via the South Pole to the Ross Sea. A supporting group, the Ross Sea party, would meanwhile establish camp in McMurdo Sound, and from there lay a series of supply depots across the Ross Ice Shelf to the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. These depots would be essential for the transcontinental party’s survival, as the group would not be able to carry enough provisions for the entire crossing. The expedition required two ships: Endurance under Shackleton for the Weddell Sea party, and Aurora, under Aeneas Mackintosh, for the Ross Sea party. Other scientific and exploratory sledging trips were planned for parties setting out from the main base as well as another party who were to remain at the base and carry out a variety of scientific work. Shackleton called his new expedition the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, because he felt that “not only the people of these islands, but our kinsmen in all the lands under the Union Jack will be willing to assist towards the carrying out of the … programme of exploration.” According to legend, Shackleton posted an advertisement in a London paper, stating: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.” Searches for the original advertisement have proved unsuccessful, and the story is generally regarded as apocryphal. Shackleton received more than 5,000 applications for places on the expedition. Eventually, the crews for the two arms of the expedition were trimmed down to 28 apiece, including William Bakewell, who joined the ship in Buenos Aires; his friend Perce Blackborow, who stowed away when his application was turned down; and several last-minute appointments made to the Ross Sea party in Australia. A temporary crewman was Sir Daniel Gooch, grandson of the renowned railway pioneer Daniel Gooch. As his second-in-command, Shackleton chose Frank Wild, who had been with him on both the Discovery and Nimrod expeditions. To captain Endurance Shackleton had wanted John King Davis, who had commanded Aurora during the Australasian Antarctic Expedition. Davis refused, thinking the enterprise was “foredoomed”, so the appointment went to Frank Worsley, who claimed to have applied to the expedition after learning of it in a dream. Tom Crean, who had been awarded the Albert Medal for saving the life of Lieutenant Edward Evans on the Terra Nova Expedition, took leave from the Royal Navy to sign on as Endurance’s second officer; another experienced Antarctic hand, Alfred Cheetham, became third officer. Two Nimrod veterans were assigned to the Ross Sea party: Mackintosh, who commanded it, and Ernest Joyce. Shackleton had hoped that Aurora would be staffed by a naval crew, and had asked the Admiralty for officers and men, but was turned down. After pressing his case, Shackleton was given one officer from the Royal Marines, Captain Thomas Orde-Lees, who was Superintendent of Physical Training at the Marines training depot. The scientific staff of six accompanying Endurance comprised the two surgeons, Alexander Macklin and James McIlroy; a geologist, James Wordie; a biologist, Robert Clark; a physicist, Reginald W. James; and Leonard Hussey, a meteorologist who would eventually edit Shackleton’s expedition account South. The visual record of the expedition was the responsibility of its photographer Frank Hurley and its artist George Marston. On August 8th the Endurance sailed for the Antarctic via Buenos Aires and the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia where there was a Norwegian whaling station. On November 5th, 1914 they arrived at South Georgia. Shackleton learnt much from the whaling captains about the conditions between there and the Weddell Sea which indicated that this was a particularly heavy ice year. The plan had been to spend only a few days collecting stores, but instead, the Endurance remained at South Georgia for a month to allow the ice further south to disperse. The Weddell Sea was known to be particularly ice-bound at the best of times and the Endurance left with a deck-load of coal in addition to normal stores to help with the extra load on the engines when it came to pushing through pack ice in the Weddell Sea to the Antarctic continent beyond. Extra clothing and stores were taken from South Georgia in the event that the Endurance may have to winter in the ice if caught in the Weddell Sea as it froze, unable to reach the continent first. They left South Georgia on the 5th of December 1914. As their ship, the Endurance approached Antarctica it became trapped by ice in Vahsel Bay. Too far from land to attempt a crossing, they planned to sit out winter in their ship and then attempt their mission in Spring. After months of waiting, it becomes clear that they will have to abandon their plan for a delayed expedition, as well as their ship. The ice has crushed the Endurance’s hull beyond repair; when the ice melts, she will sink. The new objective is to get home safely. According to photographer Frank Hurley: “The ship groans and quivers, windows splinter whilst deck timbers gape and twist. Amid these profound and overwhelming forces, we are the embodiment of helpless futility.” The Endurance finally broke up and sank below the ice and waters of the Weddell sea on November 21st, 1915. The men had saved as many supplies as they could (including Frank Hurley’s precious photo archive) before she disappeared. The 28 men of the expedition were now isolated on the drifting pack ice hundreds of miles from land, with no ship, no means of communication with the outside world, and with limited supplies. What was worse was that the ice itself was now starting to break up as the Antarctic spring got underway. On December 20th Shackleton decided that the time had come to abandon their camp and march westward to where they thought the nearest land was, at Paulet Island. Over the course of 6 months, the ice sheet has moved (at one point bringing them within sight of Antarctica, only to drift away from it), and now the closest bit of land is Elephant Island. Only 30 miles away, they set sail, optimistic that they will land that day. After a day of sailing, the position is checked, not only are they not nearing Elephant Island, the current has pulled them off course; they’re now 60 miles from land. It will take another 7 days of rowing and sailing in open boats to reach Elephant Island. Elephant Island is a desolate, frozen rock. Despite that, the men dance with joy when they finally reach it. It’s been 497 days since they last set foot on land. The plan is to spend the next winter on the island and in spring a whaling ship is likely to sail by and save them. Shackleton takes stock of their inventory; there isn’t enough food, if they spend the winter, they’ll die of starvation. Shackleton decides on a final and desperate play to save the men, he will take 5 men and sail to South Georgia Island to find help. The group of 6 men made an 800-mile (1,300 km) open-boat journey in the James Caird (boat) to reach South Georgia. From there, Shackleton was eventually able to mount a rescue of the men waiting on Elephant Island. It will take 3 months and several attempts to rescue the remaining 22 men on Elephant Island, but on the 30th of August 1916, he finally reaches them. All 22 were still alive and well. Frank Worsely (the ship’s captain): “Shackleton’s spirits were wonderfully irrepressible considering the heartbreaking reverses he has had to put up with and the frustration of all his hopes for this year at least. One would think he had never a care on his mind & he is the life & soul of half the skylarking and fooling in the ship.” Not a single man of Shackleton’s original twenty-eight was lost. And though the Endurance was lost to the sea ice, the James Caird open-boat was brought back to England and survives to this day in Dulwich College London, a living reminder of an act of remarkable courage in the heroic age of exploration.

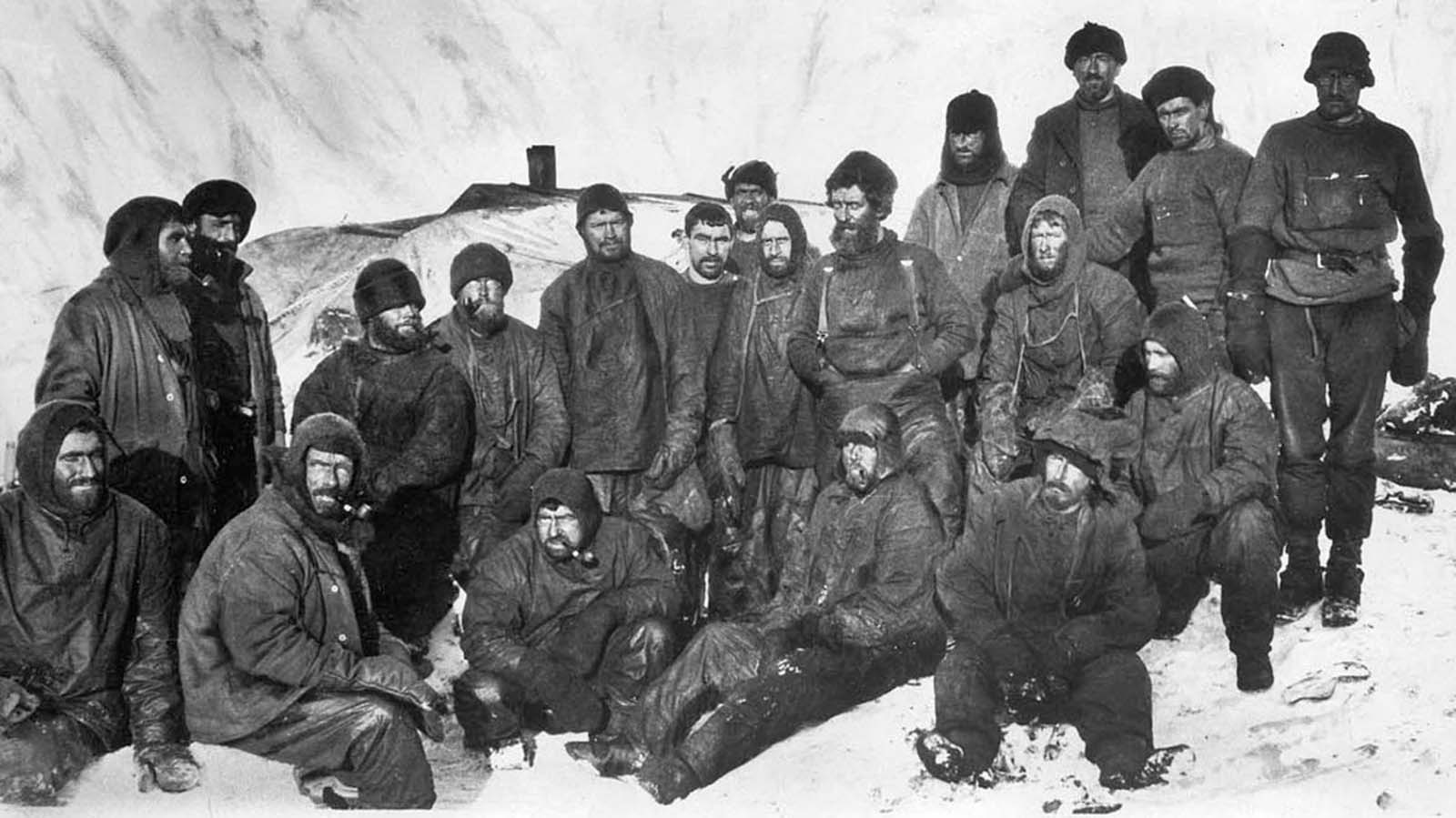

(Photo credit: Frank Hurley / Scott Polar Research Institute / University of Cambridge / State Library of New South Wales / Wikimedia Commons / Cool Antarctica). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe