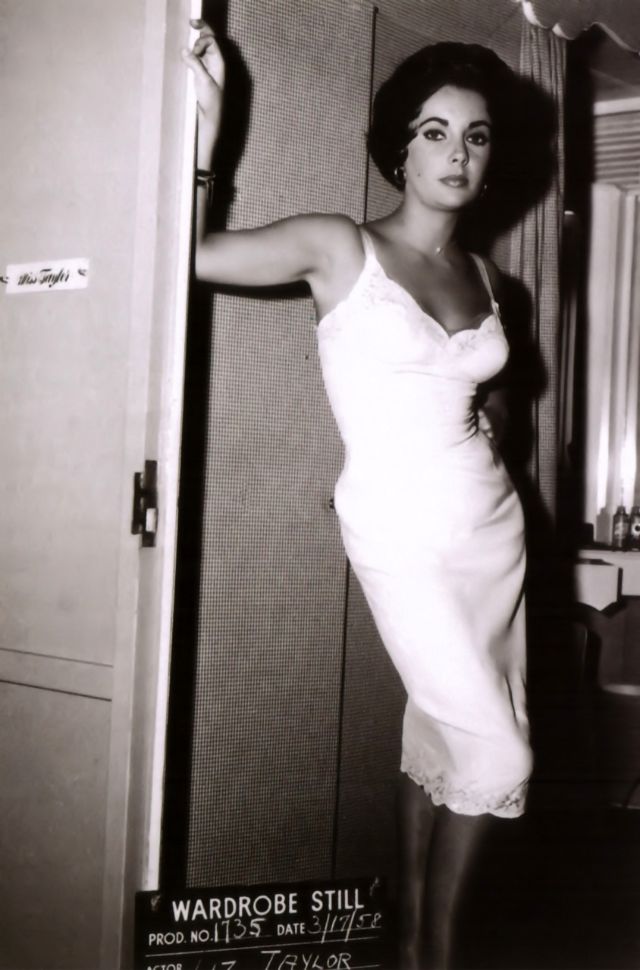

She then became the highest-paid movie star in the 1960s, remaining a well-known public figure for the rest of her life. In 1999, the American Film Institute named her the seventh-greatest female screen legend of Classic Hollywood cinema. Born in London to socially prominent American parents, Taylor moved with her family to Los Angeles in 1939. She made her acting debut with a minor role in the Universal Pictures film There’s One Born Every Minute (1942), but the studio ended her contract after a year. She was then signed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and became a popular teen star after appearing in National Velvet (1944). She transitioned to mature roles in the 1950s when she starred in the comedy Father of the Bride (1950) and received critical acclaim for her performance in the drama A Place in the Sun (1951). Despite being one of MGM’s most bankable stars, Taylor wished to end her career in the early 1950s. She resented the studio’s control and disliked many of the films to which she was assigned. She began receiving more enjoyable roles in the mid-1950s, beginning with the epic drama Giant (1956), and starred in several critically and commercially successful films in the following years. These included two film adaptations of plays by Tennessee Williams: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), and Suddenly, Last Summer (1959); Taylor won a Golden Globe for Best Actress for the latter. Although she disliked her role as a call girl in Butterfield 8 (1960), her last film for MGM, she won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance. During the production of the film Cleopatra in 1961, Taylor and co-star Richard Burton began an extramarital affair, which caused a scandal. Despite public disapproval, they continued their relationship and were married in 1964. Dubbed “Liz and Dick” by the media, they starred in 11 films together. Taylor received the best reviews of her career for Woolf, winning her second Academy Award and several other awards for her performance. She and Burton divorced in 1974 but reconciled soon after, remarrying in 1975. The second marriage ended in divorce in 1976. Taylor’s acting career began to decline in the late 1960s, although she continued starring in films until the mid-1970s, after which she focused on supporting the career of her sixth husband, United States Senator John Warner (R-Virginia). In the 1980s, she acted in her first substantial stage roles and in several television films and series. She became the second celebrity to launch a perfume brand, after Sophia Loren. Taylor was one of the first celebrities to take part in HIV/AIDS activism. She co-founded the American Foundation for AIDS Research in 1985 and the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation in 1991. From the early 1990s until her death, she dedicated her time to philanthropy, for which she received several accolades, including the Presidential Citizens Medal. Throughout her career, Taylor’s personal life was the subject of constant media attention. She was married eight times to seven men, converted to Judaism, endured several serious illnesses, and led a jet set lifestyle, including assembling one of the most expensive private collections of jewelry in the world. After many years of ill health, Taylor died from congestive heart failure in 2011, at the age of 79. Taylor was one of the last stars of classical Hollywood cinema and one of the first modern celebrities. During the era of the studio system, she exemplified the classic film star. She was portrayed as different from “ordinary” people, and her public image was carefully crafted and controlled by MGM. When the era of classical Hollywood ended in the 1960s, and paparazzi photography became a normal feature of media culture, Taylor came to define a new type of celebrity whose real private life was the focus of public interest. According to Adam Bernstein of The Washington Post, “more than for any film role, she became famous for being famous, setting a media template for later generations of entertainers, models, and all variety of semi-somebodies.” Regardless of the acting awards she won during her career, Taylor’s film performances were often overlooked by contemporary critics; according to film historian Jeanine Basinger, “No actress ever had a more difficult job in getting critics to accept her onscreen as someone other than Elizabeth Taylor… Her persona ate her alive.” Her film roles often mirrored her personal life, and many critics continue to regard her as always playing herself, rather than acting. In contrast, Mel Gussow of The New York Times stated that “the range of [Taylor’s] acting was surprisingly wide”, despite the fact that she never received any professional training. Film critic Peter Bradshaw called her “an actress of such sexiness it was an incitement to riot – sultry and queenly at the same time”, and “a shrewd, intelligent, intuitive acting presence in her later years.” David Thomson stated that “she had the range, nerve, and instinct that only Bette Davis had had before – and like Davis, Taylor was monster and empress, sweetheart and scold, idiot and wise woman.” Five films in which she starred – Lassie Come Home, National Velvet, A Place in the Sun, Giant, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? – have been preserved in the National Film Registry, and the American Film Institute has named her the seventh greatest female screen legend of classical Hollywood cinema. Taylor has also been discussed by journalists and scholars interested in the role of women in Western society. Camille Paglia writes that Taylor was a “pre-feminist woman” who “wields the sexual power that feminism cannot explain and has tried to destroy. Through stars like Taylor, we sense the world-disordering impact of legendary women like Delilah, Salome, and Helen of Troy.” In contrast, cultural critic M.G. Lord calls Taylor an “accidental feminist”, stating that while she did not identify as a feminist, many of her films had feminist themes and “introduced a broad audience to feminist ideas.” Similarly, Ben W. Heineman Jr. and Cristine Russell write in The Atlantic that her role in Giant “dismantled stereotypes about women and minorities.” Taylor is considered a gay icon, and received widespread recognition for her HIV/AIDS activism. After her death, GLAAD issued a statement saying that she “was an icon not only in Hollywood, but in the LGBT community, where she worked to ensure that everyone was treated with the respect and dignity we all deserve”, and Sir Nick Partridge of the Terrence Higgins Trust called her “the first major star to publicly fight fear and prejudice towards AIDS.” According to Paul Flynn of The Guardian, she was “a new type of gay icon, one whose position is based not on tragedy, but on her work for the LGBTQ community.” Speaking of her charity work, former President Bill Clinton said at her death, “Elizabeth’s legacy will live on in many people around the world whose lives will be longer and better because of her work and the ongoing efforts of those she inspired.”

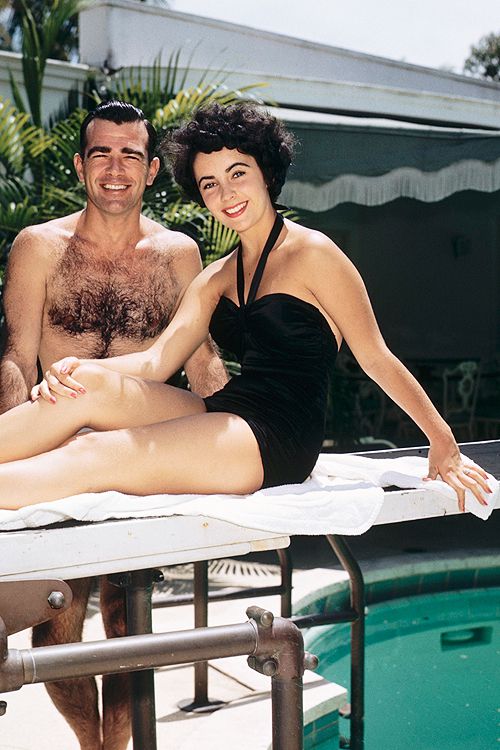

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Pinterest / Britannica). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe