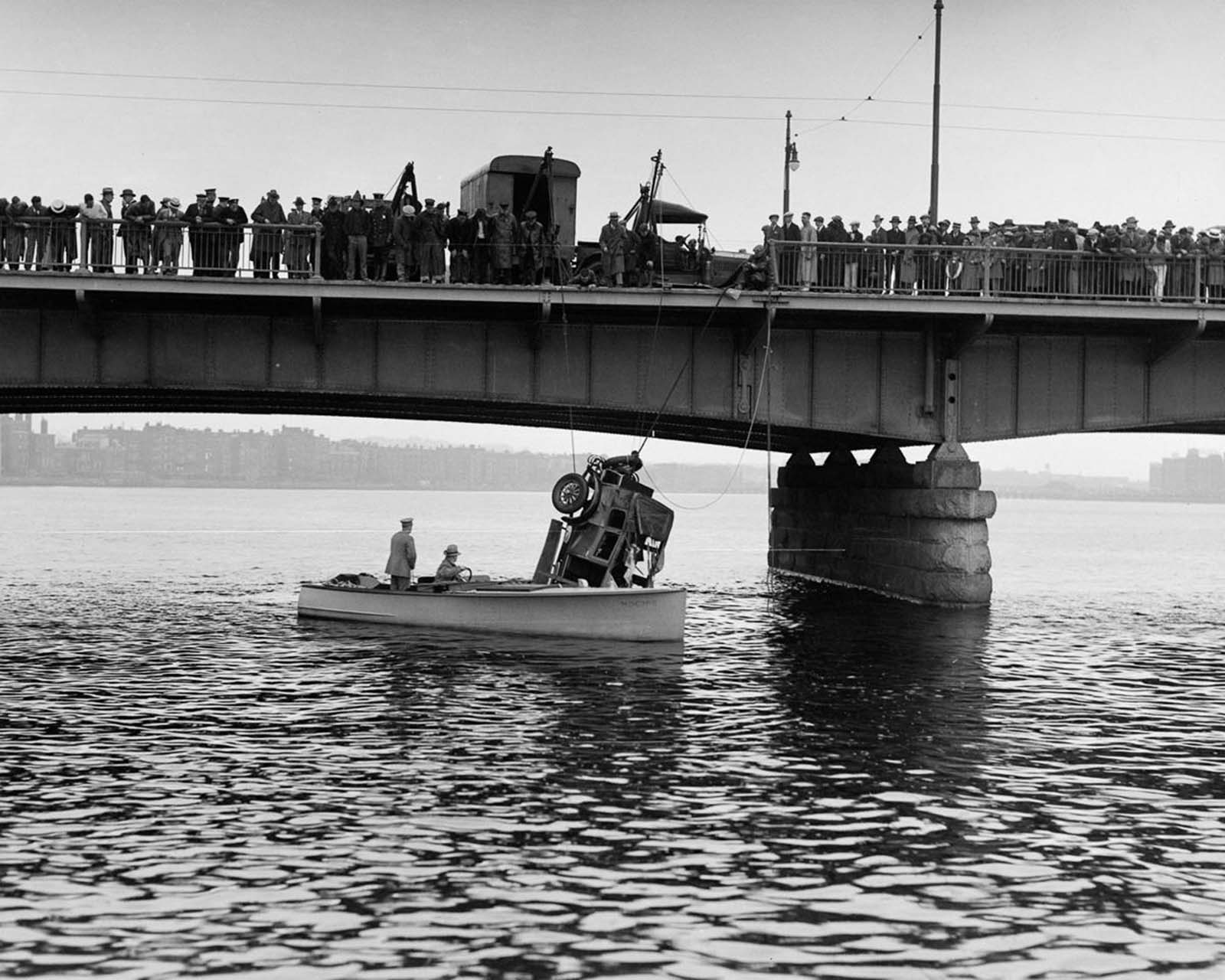

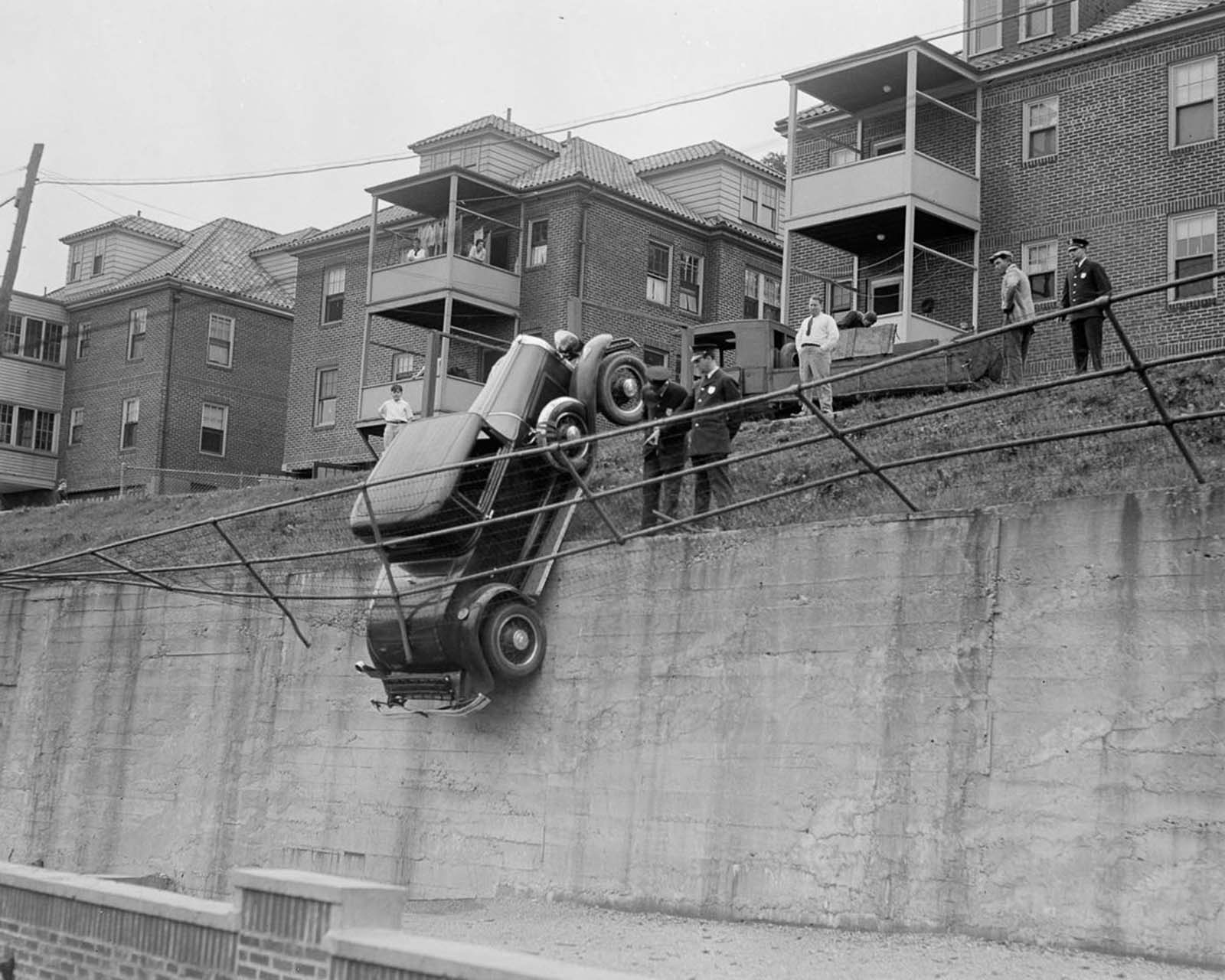

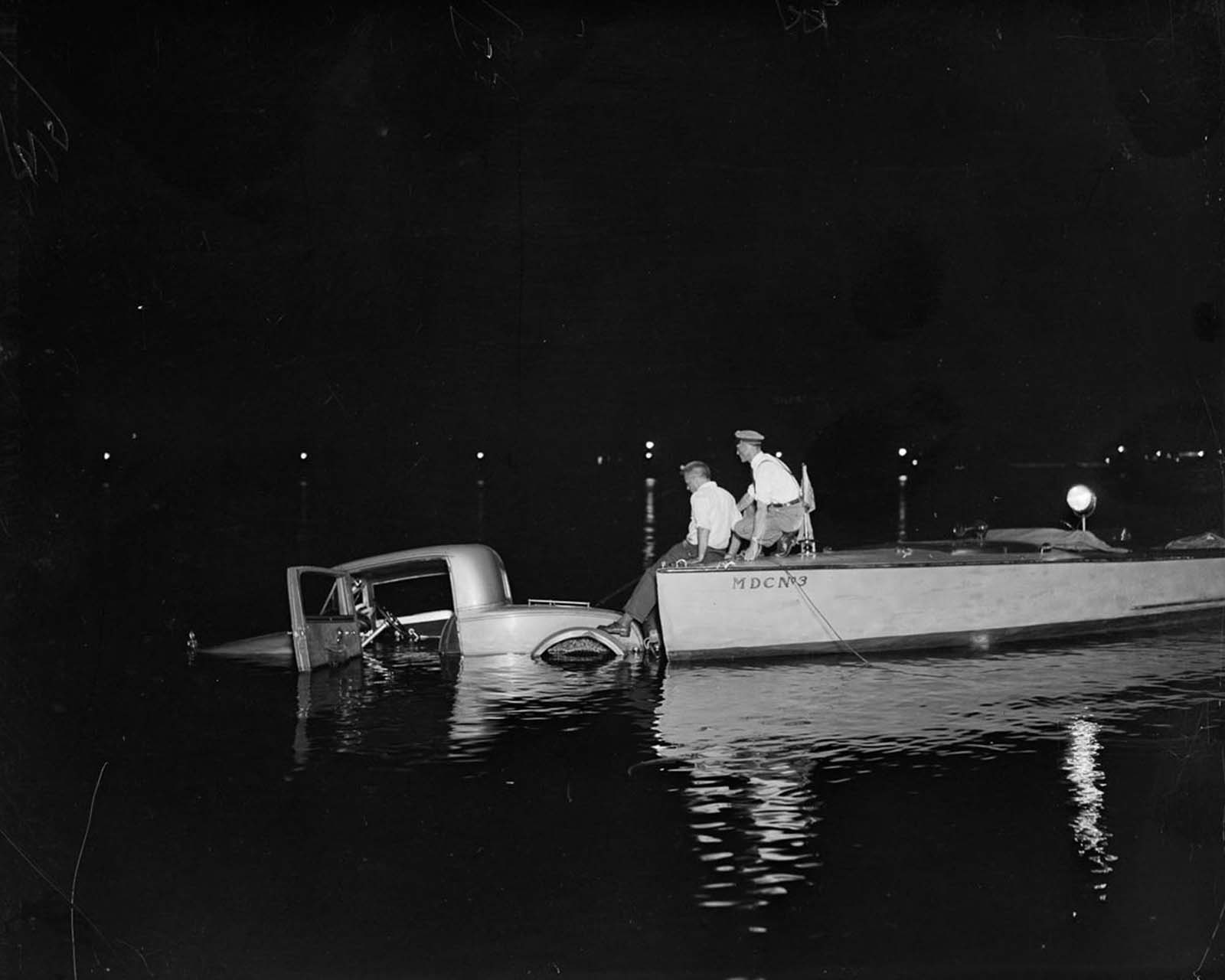

One of his favorite things was the documenting of car accidents. In the 1930s, he rushed to the scenes of hundreds of crashes, fender-benders, pileups, and captured the aftermaths in photos that ranged from morbid and tragic to bizarre and comical. What sets Jones apart from his contemporaries, and what makes his photograph collection truly great, is his keen sense of composition and human interest. As a press photographer, he was always under the pressure of looming deadlines. In addition, newspaper editors were not known for their delicacy or deference to their photographers’ skills. Given this, many of Jones’ published photos could have been harshly cropped, or otherwise changed to fit the story and the column space. Despite this, the uncropped images in this collection are always carefully composed and show an interest in the human activity taking place. Jones took hundreds of pictures of car accidents, but his focus on the crowds of gawkers and bystanders makes these otherwise grim pictures almost lighthearted, and even funny at times. Throughout the 1930s, the United States contended not only with the Great Depression but also with a nationwide panic surrounding traffic safety. In 1935, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt penned a letter to state governors, imploring them to curtail “the increasing number of deaths and injuries” related to car crashes. In the 1910s, speeding, reckless driving, collisions, and pedestrian fatalities were new problems requiring new solutions. The first remedies comprised a social response focused on controlling and improving driver behavior. By the early 1920s, the National Safety Council compiled accident statistics, held conferences, and sponsored Safety Week campaigns in cities in the hope that increased public awareness would promote careful driving. Controlling driver behavior through laws, fines, signals, and drunk driving arrests were obvious ways to decrease the fatality rate. Americans were slow to understand the importance of redesigning automobiles to make driving safer. At first, the automobile was perceived as a neutral device that merely responded to a driver’s commands and could not cause an accident. But by the late 1920s, manufacturers acknowledged that design flaws compromised safety. They introduced a technological response to safety issues, adding shatter-resistant windshields and four-wheel brakes instead of two-wheel brakes. In the 1930s, this approach evolved into a market response as automakers actively promoted new safety improvements such as all-steel bodies and hydraulic brakes. Automakers now assured motorists that modern cars were completely safe, and industry representatives contended that improving roads, licensing drivers, and regulating traffic was the key to preventing accidents. Seat belts, energy-absorbing steering columns, and padded dashboards were not installed, even though all of those devices had been invented by the 1930s.

(Photo credit: Leslie Jones Collection / Boston Public Library / National Musem of American History). Notify me of new posts by email.

Δ Subscribe